Making waves

Engineers test a bizarre bomb

On 6 June 1944, as the Allies launched themselves into vast and risky D-Day landings in Europe and as fighting continued interminably across the Pacific, scientists in New Zealand began working on a secret weapon to shorten the war.

At a military base on the Whangaparaoa Peninsula, north of Auckland, a hand-picked unit of specialists, unobtrusively called the 24th Army Troops Company, New Zealand Engineers, set about stirring up water with high explosives. Their aim—one that would not have been out of place in a James Bond film—was to perfect a technique for generating an artificial tidal surge capable of destroying coastal defences and even small cities.

The ‘tsunami bomb’, as it came to be called, was the brainchild of an American officer, Commander E.A. Gibson, who had noticed that blasting to clear away submerged coral reefs in the Pacific sometimes triggered unusually large waves. He passed on his observation to the New Zealand Chief of General Staff, Lieutenant General Sir Edward Puttick, who in turn put it before the War Cabinet.

The upshot was that in February 1944, a joint group of Americans and New Zealanders began a series of exploratory tests off the coast of New Caledonia. Admiral William Halsey, the US South Pacific area commander, was so encouraged by the results that he asked New Zealand to develop the idea further in home waters.

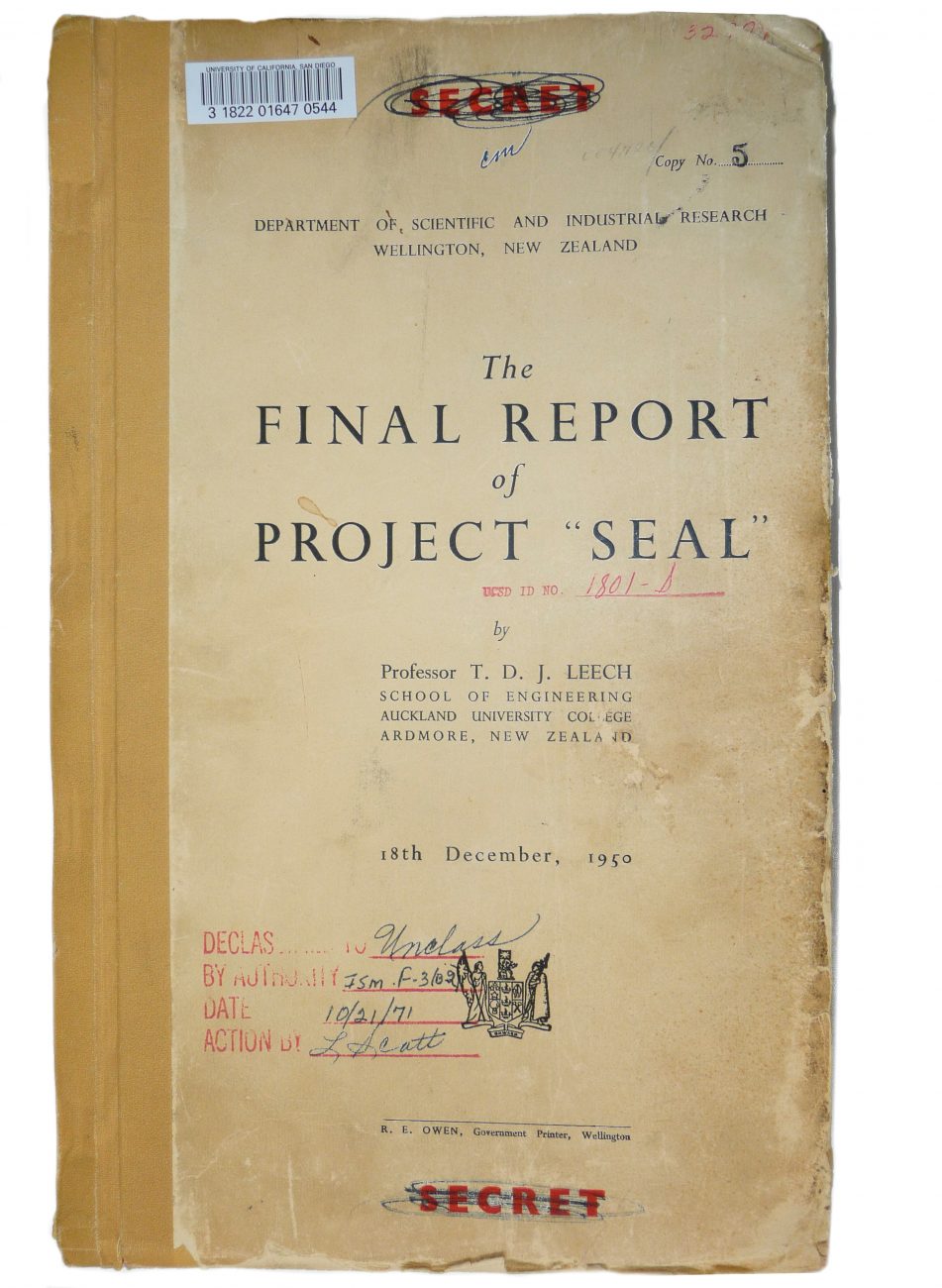

The task of heading up this research—codenamed Operation Seal—fell to the dean of the School of Engineering at Auckland University College, Professor Thomas Leech. After the outbreak of war, engineering staff had become involved in a great many military projects—from making dummy coastal guns out of telegraph poles rigged with electronic flashes to developing radio-controlled boats packed with explosives. But nothing approached the ambition of the tsunami bomb.

An earth dam was built in one of the peninsula’s valleys to create a testing pool 365 metres long and 60 metres wide, and devices were concocted for radio-controlled firing and the remote recording of waves. Over the course of seven months, the 24th Army Troops Company carried out some 3700 experiments, using charges of TNT—and occasionally contact explosive, nitrostarch or gelignite—that ranged in weight from a few grams to 270 kilograms. A meticulous photographic record of the experiments was made and the data carefully logged.

As Allied victory in the Pacific grew more certain, plans for full-scale ocean testing at Taronui Bay north of Kerikeri were cancelled. But by the time Operation Seal was wound down in January 1945, Leech had proved that a tsunami bomb was theoretically possible. Depth was critical, he concluded, but “with charges of TNT of the order of 2000 tons divided into, say, ten equal amounts and suitably disposed, wave amplitudes of the order of 30 to 40 feet are within the bounds of possibility”.

A recent survey by NIWA scientists outlining the risk to Kaikoura from tsunami shows how readily nature can accomplish what the New Zealand engineers toiled over. NIWA calculates that an underwater landslide on the rim of the coastal Kaikoura Canyon, triggered by an earthquake, could result in a wall of water 13 metres high. Leech would have known how many tonnes of TNT that wave would require.