Messages from your ex

A look through the Neanderthal genome only proves again: there’s no escaping your roots.

You are roughly 2.7 per cent Neanderthal. That’s not the cue for a joke; it’s a fact confirmed by the complete sequence of the Neanderthal genome. The DNA came from a woman found in a cave in the Altai mountains of Siberia. She lived between 50,000 and 100,000 years ago, and depending on which palaeontologist you follow, she was either a separate species from you—Homo neanderthalensis—or a subspecies of Homo sapiens. Either way, unless you’re of purely African descent, you carry some of her genes.

Evidence reveals that early humans and Neanderthals got it on regularly. They first mingled about 100,000 years ago, when early humans left Africa and migrated north into the Middle East, the Arabian Peninsula and the Nile Valley. Those human progenitors died out—they play practically no part in your ancestry—but they did feature in the Neanderthals’. They left a small bit of their DNA in the toe bone of the Siberian Neanderthal woman, and may have lent her traits that helped her kind to learn to speak.

Between 47,000 and 60,000 years ago, a second wave of H. sapiens successors moved out of Africa and into Europe and the Baltic, and apparently got straight down to fraternising with the Neanderthals they met there.

How do we know? Because in 2002, spelunkers exploring the Oase cave in south-western Romania found a very old jawbone. It was attached, 37,000 to 42,000 years ago, to a young man—one of the earliest modern humans to live in Europe. But palaeoanthropologists noticed something different about him. When they drilled into one of his teeth for some DNA, they discovered that his great-great-grandfather was a Neanderthal. Fully a tenth of his DNA had come from that other lineage—as much as four times more than we carry today. Half of one of his chromosomes was pure Neanderthal. That meant early humans and Neanderthals shared eastern Europe at least 200 years before his time, and proved that they could put their differences aside, at least for long enough to reproduce. And it wasn’t very common—the limited gene transfer seems to hint at only the occasional tryst.

What’s more, the analysis also found a faint trace of Neanderthal DNA from those earlier Middle Eastern liaisons.

The Neanderthals lived in Europe for more than 200,000 years, then promptly disappeared, not long after the great-great-grandfather of the man in the cave was born. Meanwhile, the successors of the young man went on to global supremacy.

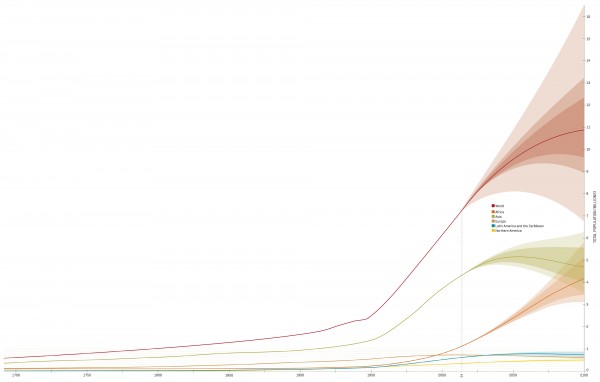

Perhaps the Neanderthals couldn’t adapt to a warming climate and a landscape that was slowly thinning from forest into savannah. Maybe they were being out-competed by modern humans. All we know is that when those humans ranged further, across Eurasia and into the Pacific, they took a little bit of the Neanderthal genome with them. Modern-day Europeans and Asians still carry between one per cent and three per cent Neanderthal DNA. (Africans don’t, because of the direction of human expansion.) That doesn’t sound like much, but because we each carry different bits, some 20 per cent of the Neanderthal genome is still around today.

So what did they leave us? Some say those ancient dalliances lent us the genetic advantage we needed to go on to global domination, but they had their consequences.

“When Neanderthals and modern humans interbred, they were actually at the edge of biological compatibility,” Harvard researcher David Reich told the Guardian. “The population had to sort out some problems afterwards, because certain Neanderthal variants led to reduced male fertility.”

The male offspring of a Neanderthal/human couple were at best marginally fertile, but more likely sterile, so their DNA soon drained from the gene pool, which explains why most Neanderthal DNA found in humans today has been handed down from females.

Reich’s study combed the DNA of 1000 people for ancient genes, and compared them to the genome derived from the Altai woman. They found that certain Neanderthal sequences popped up regularly in particular regions of the modern human genome, but their DNA was absent from other, quite large tracts.

It seems that around 80 per cent of us may have picked up some useful adaptations to the cold: genes that code for keratin production have conferred thicker, stouter hair and tougher skin. Sweat production and regulation may be at least partially influenced by Neanderthal genes.

We almost certainly acquired immunity to a range of Euro-centric diseases from them. And if you’re a red-head, you might have a Neanderthal to thank.

Not all their hand-me-downs were useful, though: it’s possible that some have left us pre-disposed to diseases such as lupus, Crohn’s disease and type-2 diabetes.

The diabetes gene is a classic instance of an ancient advantageous trait gone horribly wrong in a modern context. Neanderthals were hunter-gatherers, so they probably endured long fasts punctuated by gluttonous binges. The diabetic reaction helped them to regulate those conditions, whereas today, we do the gorging but none of the fasting. Another is that we’ve inherited certain blood-coagulation disorders from our slope-jawed relatives. Neanderthals carried a gene coded for rapid blood clotting—probably a boon when wrestling wild animals was a daily chore—but it now works against our 21st-century welfare, increasing the risk of strokes, pulmonary embolism and pregnancy complications.

Researchers at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee, compared certain contemporary Neanderthal gene variants with their H. sapiens versions and found that some may increase the risk of osteoporosis, UV-induced skin lesions, obesity and depression. But the most perplexing—almost bizarre—legacy is nicotine addiction. Of course, Neanderthals didn’t have access to tobacco (it was a native of the Americas) but geneticists think that back then, the mutation, which works on brain receptors, may have helped to attune them to beneficial substances—compounds, maybe minerals—they would have needed to maintain good health. Nowadays, the mutation just happens to pick out nicotine. Like so much of human biology, it could well be a fluke. One thing’s for sure—it’s a passing phase: The human story has plenty more chapters to go, assuming we don’t crash the planet first, and it’s nice to think we still carry a few paragraphs from our ancient past.