Inside the Land March

Te Rōpū o te Matakite: the seers, the ones with foresight. That’s the name of the group that revered leader Dame Whina Cooper led on a 1000-kilometre march from the Far North to Wellington in 1975, protesting against more than a century of colonial laws designed to alienate Māori from their land.

On the estuarine Whakarapa mudflats, in the Hokianga, a young wāhine hiked her mud-stained skirts to mid-calf, dug her spade into the dirt and heaved it aside. At her back other Māori youth were busy shovelling, laughing and singing as they worked. Freshly carved ditches stretched across the flats. But the group weren’t digging the ditches. They were filling them in.

The year was 1914, and the young leader was Whina Cooper, then aged 18. For mana whenua, the estuary and mudflats were a prized source of kaimoana when wet, the perfect place to race their horses when dry, and provided access to the sea—and had never been sold. But local farmer Bob Holland had obtained a lease from the government without Te Rarawa’s knowledge or consent, and set about draining the swamp, intent on sowing grass and grazing stock.

Whina’s father, influential Te Rarawa chief Heremia Te Wake, worked to overturn the lease in court and through his political connections. Whina, already showing great “ihi, mana and wairua” (ihi being the quality in leaders that inspires awe) proposed the peaceful community protest in support.

Her band filled in the drains as quickly as the farmer and his sons could dig them—until a constable arrived with summonses for trespass for all—except Whina.

It was her first tautohetohe (argument or dispute) over the whenua on which she was born. Her brush with the law had no effect: the lease was withdrawn and the mudflats saved.

Throughout much of the 20th century, it was commonplace for Māori to be separated from their land against their will. With few opportunities to participate in Pākehā commerce, little access to development capital, and increasing pressures to assimilate, many Māori saw sale as the only way to survive in te ao hurihuri, the changing and colonial world.

Whina knew otherwise. Her father wrote in his will: “Do not sell the land to the Pākehās, even if you have no possessions. If you remain strong and remain on your land, the day will eventually come when you will have money, but if you sell you will have nothing and the ones who will suffer will be your children and your children’s children.”

As Whina grew older and came to prominence as a leader, the losses continued, driven by legislative changes designed to further force the alienation of Māori land. In 1953, prime minister Sidney Holland pressed for the Māori Affairs Act to be used as a tool to legally appropriate ‘unproductive’ Māori land. In 1967, an amendment to the Act made it compulsory for any Māori freehold land with fewer than five owners to be transferred into general land title, and further made it easier for “uneconomic” Māori land to be compulsorily acquired and sold. A mood of righteous discontent emerged.

In March 1975, at the age of 80, already a leader of great mana, Whina attended a hui about land alienation at Te Puea marae in Māngere Bridge, Auckland. What was to be done? Celebrated poet Hone Tuwhare later reported Whina’s words on the hīkoi to come: “Good gracious, if we let them take what is left, we will all become taurekareka [slaves]. Do we want that?”

A bold new approach was needed. Several groups united under the banner of Te Rōpū o te Matakite, and asked Whina to lead. She proposed a march. They would walk the length of Te Ika a Māui, stopping at rural and urban marae to enlist support and debate ideas, before arriving at Parliament to present prime minister Bill Rowling with a public petition and a Memorial of Right (a large, single-sheet document holding the signatures of ra-ngatira and kaumātua). They would demand an end to monocultural laws that pushed Māori off their land, and the enactment of those which reflected Māori cultural values. Key laws that were problematic were the Māori Affairs Act 1953 (and ensuing amendments), the Town and Country Planning Act 1953, the Counties Amendment Act 1961 and the Rating Act 1967.

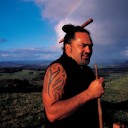

Whina’s energy, reputation and whakapapa brought together threads of resistance from across te ao Māori, from the leaders of official organisations such as the Māori Women’s Welfare League and the New Zealand Māori Council, to more outspoken activists such as Ranginui Walker, Tame Iti and Titewhai Harawira of activist group Ngā Tamatoa.

She insisted the movement had to be above reproach. “We cannot afford to be an undisciplined, uncontrolled rabble… Drink, alcoholic that is, will be prohibited.” No signs or placards would be carried. The sacred hīkoi would be heralded only by a pouwhenua representing land occupation and a single white flag representing te Matakite—which was never to touch the ground until all land claims have been resolved (it lives at Te Kōngahu Museum of Waitangi today—off the ground). Participants had to be fit, too. “Remember, if you break down, you place extra burdens on those who organise the march.”

On Māori Language Day, September 14, 50-odd whānau departed from Te Hāpua, led by Whina and her mokopuna Irenee Cooper in those iconic first steps, captured by New Zealand Herald photographer Michael Tubberty.

Activist and author Tama Te Kapua Poata, a marshal on the march, recalled how difficult the initial stages were. “On the first leg of the journey, the marchers weren’t fit,” he wrote in his memoir, Seeing Beyond The Horizon. “They were hobbling and getting blisters. The first marae we stopped at was about 25 miles out of Te Hāpua. People just collapsed after that first leg.”

A Pākehā nurse materialised, followed by bandages and medical supplies—typical of the support that grew as the march headed south and numbers swelled.

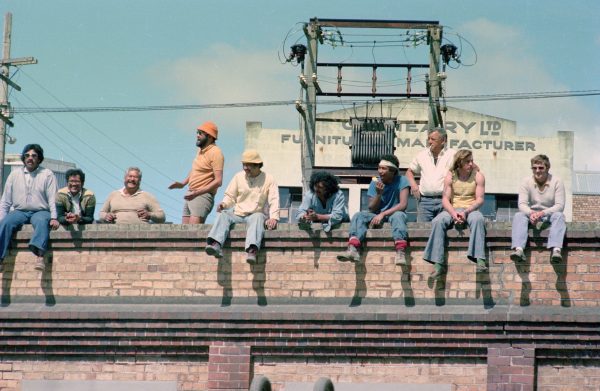

Week by week, the marchers grew fit, and as media coverage intensified, so, too, did sympathy from across cultures, generations, classes.

Telegrams of support came from as far afield as Sweden. During the hīkoi, Tuwhare wrote:

it won’t be a lonely walk

people all around and mostly young

From blue, brown with bits more added

Right on up to off-white

By the time they arrived at the Beehive—still under construction at the time—and presented their demands, numbers had swelled to about 5000 marchers, with the rest of the nation watching on TV. The march brought Māori concerns into the mainstream, and helped politicise a generation of Māori. In the words of the authors of Protest Tautohetohe, it “ignited an irreversible change in the relationship between Māori and the Crown”.

Te Rōpū o te Matakite built on the long Māori tradition of agitating against Crown oppression, combining a century of political petitioning with the peaceful resistance of Parihaka. Their hīkoi paved the way for modern protest movements including Bastion Point in 1978, Pākaitore-Moutoa Gardens in 1995 and Ihumātao in 2019. But the renowned pepeha of the Land March, “not one more acre of Māori land”, did not prevent further unjust dispossession.

Since 1975, land under Māori ownership dropped from two million hectares to 1.2 million, only increasing slightly from 1995 onwards under Treaty of Waitangi settlements to 1.47 million hectares today. Yet, while there is still one acre of whenua left to protect, the spirit of ngā tautohetohe, Māori protest, will forever be alive:

Ka whawhai tonu mātou! We will still fight, we will always fight!

Ake! Ake! Ake! Forever more! Forever more! Forever more!