Time machine

Joseph Stalin figured out how to retouch history, without Photoshop.

A photographer wields an instrument of history. But reality is a matter of perspective. Detail cropped out is as important as that which the photographer has decided to include in the frame. Long lenses can create relationships where none existed, wide-angle lenses exaggerate distance, and a short depth-of-field allows a photographer to decide on behalf of a viewer where the focus of an image should be.

Then the ultimate privilege, the photographer decides for all the world when the shutter should be released.

But why should the writing of history stop there?

By the 1930s, the printed photograph had become a device of political power—a token of truth, a statement of undisputable reality. And for Joseph Stalin, a time machine of sorts.

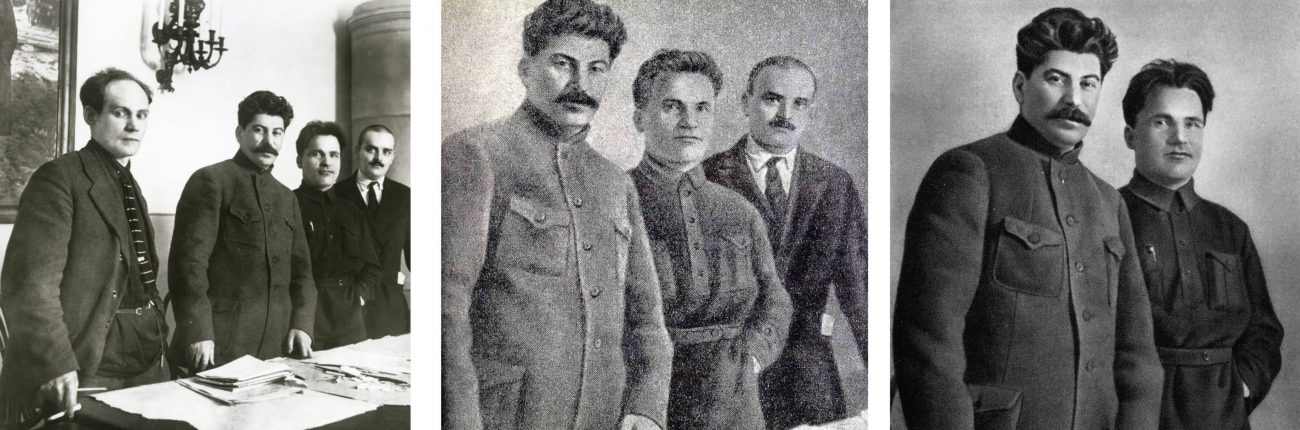

The Great Purges, orchestrated to remove dissenters from the Communist Party and consolidate the authority of Joseph Stalin, featured years of political repression from 1934, widespread public surveillance, incarceration of government officials and arbitrary executions, largely overseen by Nikolai Yezhov, then head of NKVD, the Soviet secret police.

Hundreds of thousands of victims were accused of political crimes and conspiracy, and were executed or sent to the Gulag labour camps. Yezhov had to paper over the cracks left by their disappearance. It was not enough that they vanished from the present, NKVD also required that they were erased from the past. Paper records were redacted or entire chapters torn from books, photographs were ripped out, or subjects drastically cropped out of existence. In some instances, faces were physically rubbed out with ink or scratched away.

Sometimes these were acts of government censors, other times the work of vigilant political vandalism by librarians and teachers fearful of becoming an enemy of the state should their collections contain records of politically inconvenient persons.

History became a scramble of lies upon lies, an architecture of political manipulation and paranoia so complex that Yezhov’s censors created a Summary List of banned titles and an army of librarians to scour libraries, bookshops and private collections to remove them. Publishers were leaned upon to alter images using scalpels—literally cutting and pasting history together by hand. Other works vanished into ‘closed sections’ of government archives.

Notable disappearances required a more delicate approach—painting the edges of knife-work with ink, or carefully airbrushing a political opponent into the background.

But this was only half the picture. Stalin had enjoyed a short political career. There were probably less than a dozen pictures of the man before he was appointed General Secretary in 1922.

“For a man who claimed to be the standard-bearer of the Communist movement, this caused grave embarrassment, which could only be overcome by painting and sculpture,” writes David King in his book, The Commissar Vanishes. “A whole art industry painted Stalin into places and events where he had never been, glorifying him, mythologising him.”

Yezhov’s photographic manipulation allowed Stalin to step in and out of the sliding doors of history, appearing at the appropriate moments in political history, erasing enemies from instances in which their presence became politically inconvenient. He could time-travel, and retouch history as he went.

“So much falsification took place during the Stalin years that it is possible to tell the story of the Soviet era through retouched photographs,” says King. But why was the standard of retouching often so crude? “Did the Stalinists want their readers to see that elimination had taken place, as a fearful and ominous warning? Or could the slightest trace of an almost vanished commissar, deliberately left behind by the retoucher, become a ghostly reminder that the repressed might yet return?”

By 1938, the Great Purge began to collapse in on itself. Stalin and his circle realised it had gone too far. The orders of systematic repression were repealed, outstanding death sentences suspended and Nikolai Yezhov relieved of his post.

In the end, Yezhov himself would be edited out of Stalin’s history too. He was delicately lifted from a photograph of the pair walking beside the White Sea Canal, and the background replaced with shimmering water, barely a ripple out of place.