Night moves: The world of moths

Moths can be regarded as a domestic inconvenience. They spin in awkward orbits about lamps, invade our cereal, snack on our woollens. But look closer; theirs is a remarkable world of gluttony, dramatic transformations, mind-bending scents and wild sex.

The flashy red Cinnabar moth, Tyria jacobaeae, was imported by the Cawthron Institute in 1929 to combat ragwort, an invasive weed that can poison livestock. Cinnabar moths munch through the flowers, limiting seed production and completely defoliating plants if larvae numbers are high. With the help of breeding programmes in the 1980s, this moth is now established nationwide.

While the Cinnabar moth might be a farmer’s friend, the native porina moth devastates pasture, and the common forest looper, Pseudocoremia suavis, also a native, moved from its natural host, the beech tree, to defoliate plantations of pine and Douglas fir. The guava moth caterpillar bores into fruit—citrus, feijoa, guava and macadamia. The light brown apple moth’s leafroller caterpillar rolls and binds leaves with silk on 265 plant species, causing hundreds of millions of dollars in damage to foliage and fruit in orchards and plantations. And Aucklanders will recall with consternation the aerial spraying campaign of 2006 to rid the western suburbs of painted apple moth that happily defoliated 92 plant species.

For decades, scientists have engaged in a battle of wits with such invasive species. One way to beat them, it has been found, is to employ the moths’ own carnal urges. While unimaginable gluttony is the prerogative of the caterpillar phase, for a winged adult moth, foremost on the agenda is sex.

Male moths are easy to seduce: in order to breed, the females release a pheromone plume, an assortment of acetates and aldehydes that advertise her location. The molecules alight on the male’s feathery antennae and nerve impulses spark the ganglions in the brain.

The ratio of chemicals is specific to the species, a factor biological control scientists have turned to their advantage in controlling native and exotic pest species such as leafrollers and codling moths. Since the 1800s, orchardists have been able to disperse synthetic hormones as “lure and kill” systems, or simply saturate the air, creating a pheromone noise termed ‘mating disruption’ so that the male moths can’t possibly locate the females.

These techniques, along with introduced parasitoids, sterile insect release and selective insecticides are all part of a new bag of chemical tricks with which scientists can protect New Zealand’s environment and economy from the ravages of introduced predators.

While New Zealand has 24 species of butterflies, the over whelming majority of the Lepidoptera order found here is comprised of moths—at least 1700 species, 90 per cent of them found nowhere else in the world. They range from gossamer-thin, delicate beings to bombastic, whirring machines of the night. Some are even flightless. Moths are diverse; mostly nocturnal, many diurnal, some vibrant with bright greens or yellows, some—such as the primitive Izatha taingo infused with the colour of their lichen-clad surroundings, imperceptible to predators until they move.

Many species are host-specific, a feature which has been to their detriment in the modern world—Archyala opulenta larvae can grow only in the dung of the endangered short-tailed bat, and Houdinia flexilissima larvae are found only in the thin stems of an endangered rush-like plant, Sporadanthus ferrugineus, which is confined to just three wetland sites in the Waikato.

Generally speaking, moths can be described as creatures of the night which hold their wings horizontally when at rest and possess feathery vibration-and pheromone-sensing antennae with tapering ends. Butterflies typically fly during the day, fold their wings together at rest and have smooth antennae which terminate in clubs. But the terms moth and butterfly are not recognised in scientific classifications and many species in the Lepidoptera order defy this common description. New Zealand’s ensemble is no exception: some moths, especially in the alpine zones, are brightly coloured and fly during the day, and some of the butterflies would be lost in collections with their muted and unremarkable wings.

“One way to look at it,” says South Island entomologist Brian Patrick, “is that butterflies are just a few sophisticated, highly evolved families of moths. In some languages, the word for butterfly and moth is the same.”

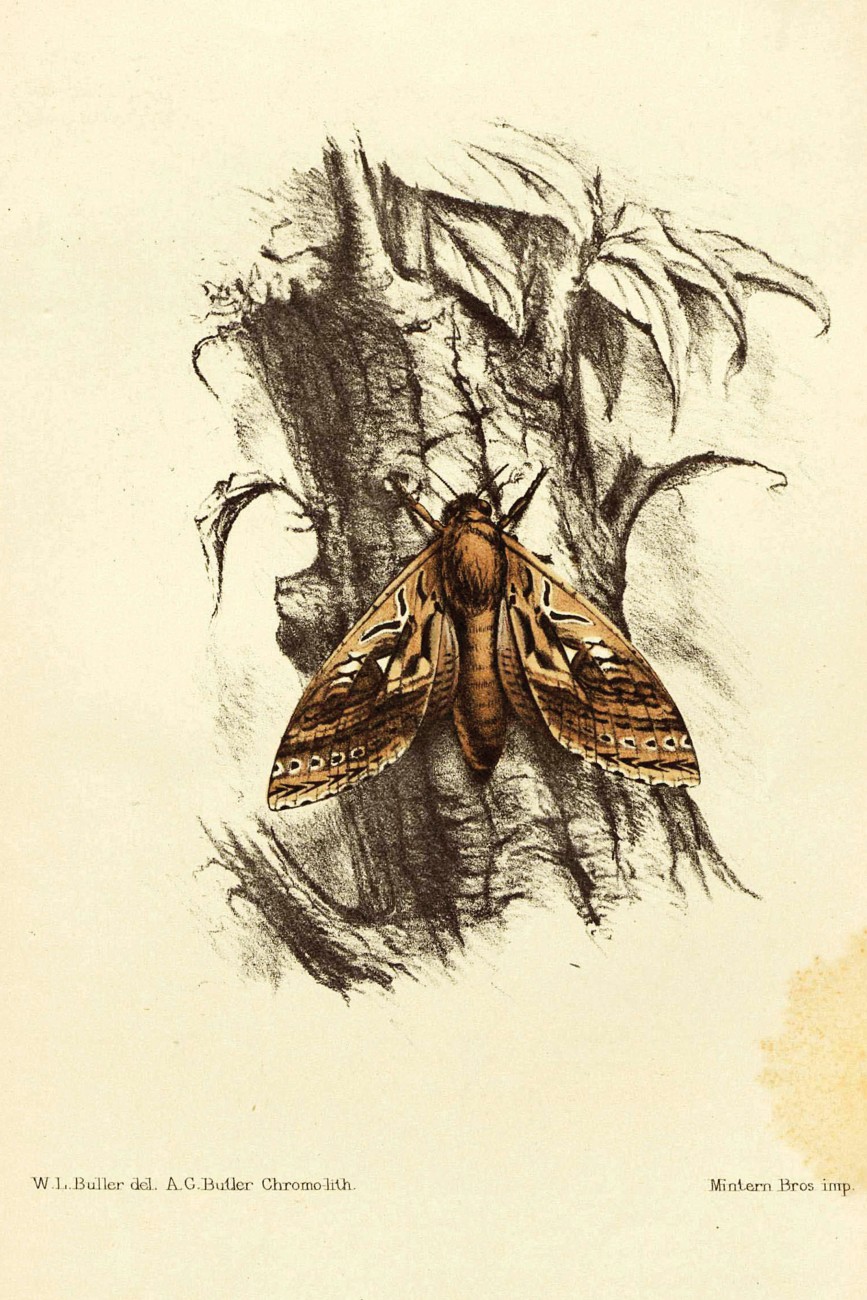

Patrick has studied the swift moth Aoraia for decades. Aoraia larvae live in swamps and wetlands where sphagnum moss abounds, and emerge on damp and humid nights. The female moth sits flightless on the ground, its reduced wings unable to carry the weight of its body. Sir Walter Buller, a Victorian ornithologist who wrote the definitive tome History of the Birds of New Zealand, contributed to the world of Lepidopterans as well when, while searching in the Ruahine Ranges for huia in 1867, he came across the colossal Aoraia mairi, a species with a 150 mm wingspan. He described it and sent a specimen to England, but neither the specimen nor the wild species was ever seen again.

Patrick’s current research focuses on the genus Notoreas, a colourful day-flying moth thought to include 45–50 species distributed from Northland to Stewart Island, from coasts to mountains. They’re beautiful, undescribed and elusive, he says, “all the things that a moth-hunter likes”.

To collect Notoreas specimens, Patrick embarks on light-trapping field trips, sometimes driving for hours into the wilderness with a sheet and a sodium lamp to summon his subjects. While it is possible to disperse tailor-made cocktails of pheromones to attract specific species, light-trapping allows moth enthusiasts to record nocturnal species that are present in an area.

“It’s the pinnacle of enjoyment for a moth lover,” Patrick says.

Small flies and caddis arrive first, followed by chafer beetles, porina moths and small moths. Larger moths follow, some not arriving until after midnight.

On a typical summer’s night, 50–80 species can be observed with equipment no more complicated than a sheet and a light source. In ideal conditions—warm, overcast nights with no moon and minimal wind—thousands of moths representing more than 100 species can gather about the lamp, the confused creatures fluttering into hair, faces, clothing. It’s not unusual to swallow a few.

Collected specimens are transferred to a portable fridge in the car to calm them (where they lie still alongside the chocolate that Patrick considers just as mandatory for the light-trapping as the rest of the equipment). Back in the lab, the moths can be examined in detail. And like forensic pathology, the smallest clues may provide the solution to the most vexing mysteries. One tiny moth has changed our understanding of the past 80 million years of New Zealand history.

[Chapter Break]

Many of the large groups of ‘highly evolved’ moths are not present in New Zealand. Instead, this country crawls with unique and primitive species, their larvae eschewing flowers targeted by more evolved species and instead devouring lower-order plants such as mosses, algae, fungi, lichens, leaf litter and the wood of fallen trees.

New Zealand’s primitive species have helped entomologists to understand the evolutionary path of moths and butterflies and, intriguingly, the process and timescale for the break-up of the Gondwanan supercontinent, which included the continental land masses of South America, Africa, New Zealand, Australia and Antarctica. Was New Zealand completely submerged during the ‘Oligocene drowning’ (in which the Zealandia continent sank 34–24 million years ago) or did pockets stay above the waterline? Was there continuous land between New Zealand and New Caledonia? The answer to some of these largest questions of palaeogeology may flutter in the form of a tiny metallic moth.

Moths in the family Micropterigidae are found worldwide. They live relatively sedentary lives in forests and are so primitive in form that the adults grind pollen with their mandibles rather than sip nectar, hence their common name ‘jaw moths’. This feeding behaviour is typical of the earliest interactions between moths and flowers, as if this moth’s evolution was frozen in time. (Later, when plants ‘realised’ that having nectar was a better sacrifice to feed the pollinators, other Lepidoptera species developed long, unfurling proboscises to take advantage of this sweet, liquid food source. Jaw moths, however, just never moved on.)

Sabatinca is a genus of this ancient moth family and is found only in New Zealand and New Caledonia.

Entomologist George Gibbs compared the DNA of the Sabatinca genus in both countries with long-extinct species in the fossil record. He discovered that Sabatinca began diversifying on the Zealandia continent as it split from Gondwana 83 million years ago, while the New Caledonian species could have colonised that island as early as 60 million years ago.

Gibbs’ results indicate that New Zealand was not entirely inundated during the Oligocene, and that New Zealand and New Caledonia were probably connected for some time. It also illustrates how the history of massive continents can be stored in the genetic memory of their smallest inhabitants for millions of years.

[Chapter Break]

Lining the walls of the Landcare Research facility in Mt Wellington, Auckland, are framed specimens of exotic atlas moths, contrasting with spectacular macro photographs of their smaller local cousins. Filling a laboratory—strictly regulated to 48 per cent humidity and 18ºC—are chests of drawers brimming with hundreds of thousands of little moths, stuck through with pins. Termed the ‘synoptic collection’, it’s a summary of New Zealand’s moth species using the best-preserved specimens, many of them collected by Alfred Philpott from the turn of last century.

Native moth expert Robert Hoare has the task of poring through the massive collection using Philpott’s technique of classifying moths according to the genitalia of the male of the species, an area of study integral to the world of insect classification.

While other physical characteristics such as markings and wingspan—can vary within a species, the male sexual organs are very different. They have unique grooves, hooks, valves and features which make each as unique as keys for a lock. (Some are embellished with alarming spikes called cornuti. In the genus Ixatha, they snap off inside the female during mating, possibly to prevent her mating with another.)

By characterising the genitalia, Hoare is working towards correctly describing New Zealand’s Lepidoptera species, consolidating some that were thought to be different species, and perhaps discovering new ones in their midst.