A touch of guilt

Sensational trial sets legal precedent.

When 23-year-old Dennis Gunn was handed a two-week sentence in 1918 for evading military service, he could scarcely have imagined that just two years later, his fingerprints, taken at the time of his conviction, would be enough to see him swing for murder. Yet, when, in a landmark verdict in May 1920, a jury found him guilty of a fatal shooting and burglary in Auckland, it was almost entirely due to fingerprint evidence.

At about 9pm on Saturday, March 13, 1920, Annie Braithwaite arrived home to find the back door open and her husband, Ponsonby postmaster Augustus Braithwaite, sprawled face down on the kitchen floor. He had repeatedly been shot, catching a bullet in the abdomen, and another in the throat. A third was lodged in the wall above the mantelpiece. The bunch of work keys he invariably carried in his hip pocket were found to be missing, and when police officers hastened to the nearby post office, they found it had been ransacked. A cash box lay open on the strongroom floor and another, seemingly untouched, sat on a shelf. In the telegraph room a third box, which had also been forced open, lay amid a scattering of coins.

The next night, a detective sergeant was despatched on an 18-hour train journey to police headquarters in Wellington with the three cash boxes, on which fingerprints had been found, and a list of 23 suspects. But examination by a specialist at the criminal registration branch, which held 230,000 unique fingerprints, drew a blank.

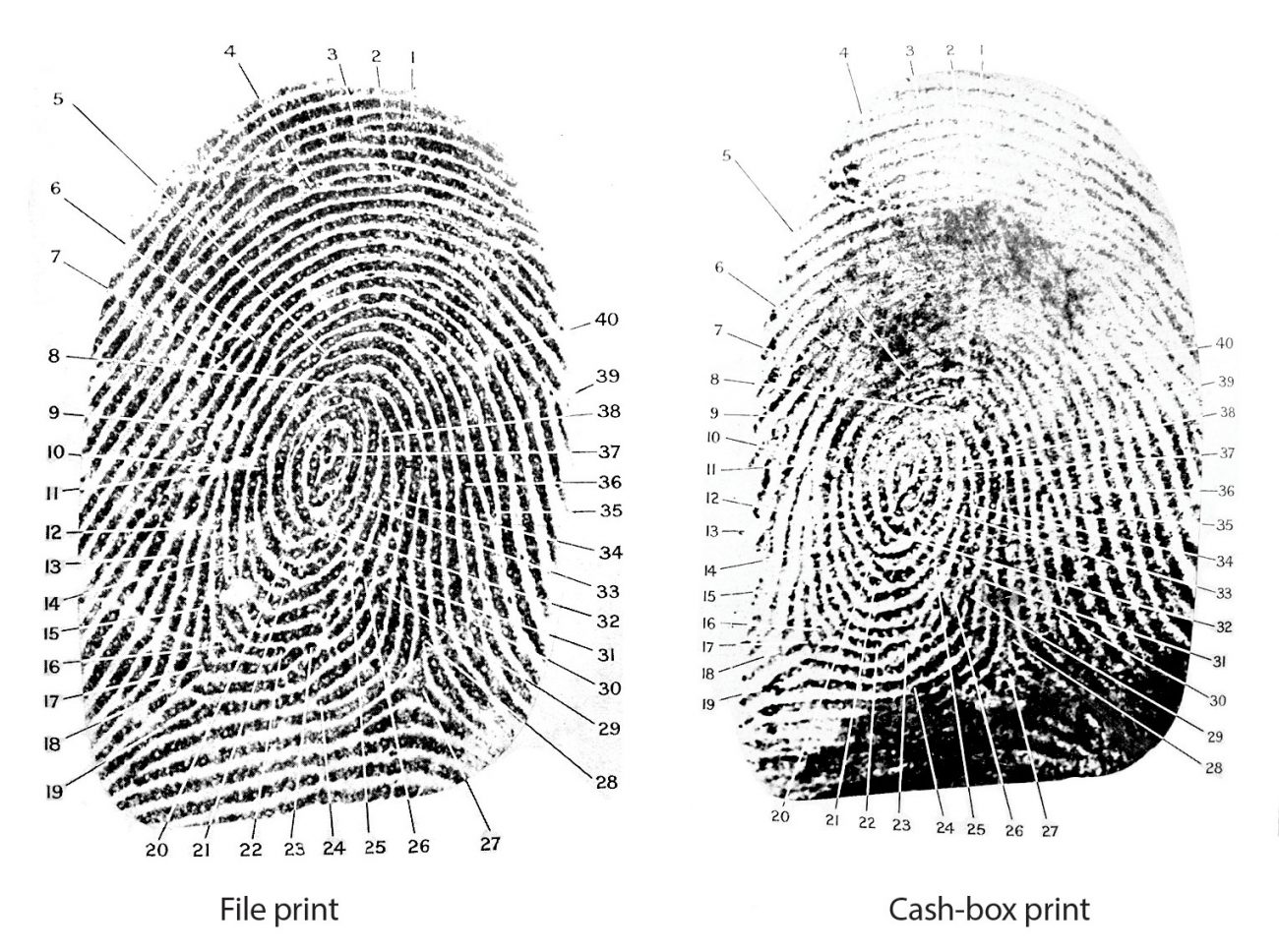

Then, the police had a stroke of luck. A former prison warden who knew Dennis Gunn from his earlier incarceration came forward to say that several times on the day of the crime, he had noticed the one-time inmate near the post office. Gunn’s name was telegrammed to Wellington, where his prints were on file, and they were found to match several on the cash boxes.

Gunn was immediately taken into custody, and police searching an overgrown gully near his home discovered a canvas bag containing coins, ammunition, and three revolvers—one of them recently fired. A second bag with money and the missing keys was also found, along with a jemmy that matched the tool used in the robbery. Prints lifted from the used revolver were found to match Gunn’s—the long-suffering detective sergeant having made a second journey to Wellington.

During the trial in the Supreme Court at Auckland, the defence lawyer repeatedly questioned the forensic value of fingerprint evidence. It was, after all, a new science, the first book on the subject having been written as recently as 1892, by a cousin of Charles Darwin.

However, the presiding judge, Sir Frederick Chapman, dwelt at length in his address to the jury on the uniqueness of individual prints, the law of probabilities, and the impartiality of the Australian fingerprint expert who had assisted with the investigation. The jury took just over two and a half hours to reach a guilty verdict.

At 8am on June 22, Dennis Gunn stepped from his cell and took a dozen paces across the prison yard to the waiting scaffold.

“The result of this trial is finally to dispose of all attempts to question the conclusiveness of this class of evidence,” noted the official report of the trial in 1921, “and to prove the truth of the remark… that a man who leaves a clear finger-print upon an object leaves there an ‘unforgeable signature’.”