Too tasty for its own good

With its bright-red flowers shaped like a parrot’s beak, ngutukākā—also called kākābeak—is distinctive and delicious. Only 108 plants remain in the wild in Aotearoa, but many more grow in the United Kingdom due to the efforts of an English collector and gardener in the 1830s. Now, the descendants of these plants are returning home.

Uncle Bogs has always been green-fingered. He was a middle child among 12, and gardening and gathering kindling were his chores. Growing things became almost second nature. At school, he won competitions where kids were given seeds to grow at home, because he’d always produce the most luscious lettuces.

Today, Uncle Bogs’ vast garden just north of Tokomaru Bay is both a māra kai and a haven for ngutukākā. Between his main home and the shed, which brims with curing bundles of elephant garlic, old ngutukākā bushes sprawl. Their straggly branches bend down to become roots for new plants. Chickens run between them, and a freshly slaughtered pig hangs off a tree at the back. The nursery, secluded at the back of the garden, is fenced off to keep animals out and to protect hundreds of fresh seedlings, all progeny of wild plants. Apart from the vegetables, the only non-native plants here are five rose bushes: one for each of Uncle Bogs’ daughters.

When Department of Conservation (DOC) ranger Graeme Atkins hands Uncle Bogs a small parcel of seeds, that schoolboy competitive streak sparkles again. The seeds are a treasure—they go back to ngutukākā plants collected and taken to England 200 years ago. Back then, ngutukākā thrived along the North Island’s east coast, from Hawke’s Bay to the Bay of Islands, and on Great Barrier Island, splashing coastal cliffs and the tops of hills with colour—and they were grown, traded and prized by local hapū. The plant all but disappeared from the wild with European settlement, but it has been growing in England ever since the early 1800s. In 2012, seeds from London’s Kew Gardens were returned to New Zealand. Now, Uncle Bogs is one of the people helping to re-establish ngutukākā on its home turf.

[Chapter Break]

The seed parcel comes from a ngutukākā plant just down the road at the Mangatuna school, which in turn is the progeny of seeds that came from Kew.

At Mangatuna, mature ngutukākā grow around the main entrance and seedlings stretch along the driveway. One of the many things the kids have rediscovered about the ngutukākā growing on their grounds is that the green seedpods are pretty tasty. They sampled quite a few before the summer holidays.

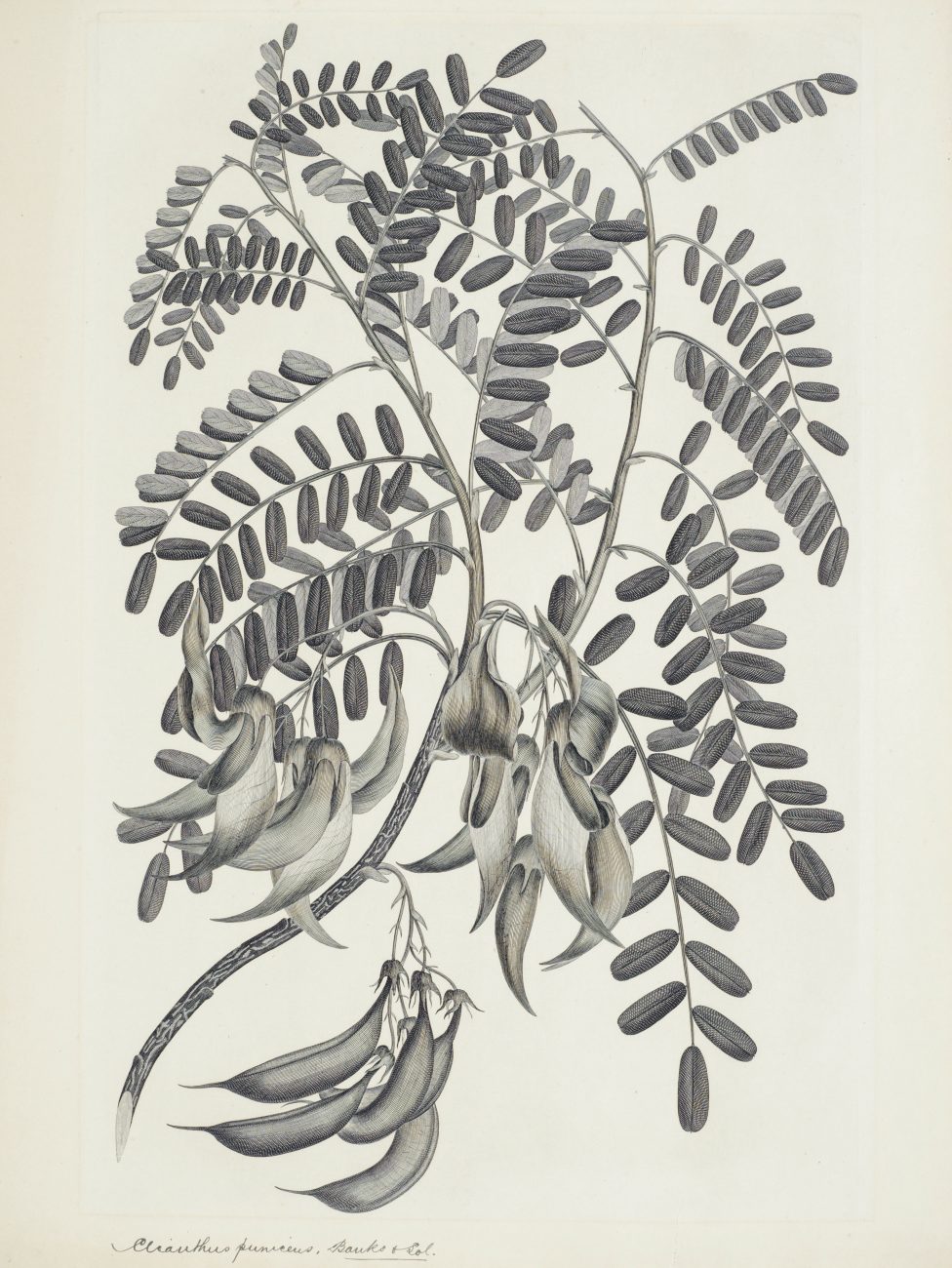

When I visit the Kew plant, there are a few ripe, darkened pods still hanging off its tall, straggly stems—depositories of a genetic line that links back to a time when ngutukākā were still plentiful. The plant is named “beak of the parrot” after the shape of its pendulous bright-red flowers, and in garden centres it’s called kākābeak—and it’s popular. But the cultivar sold commercially represents a mere sliver of the species’ genetic breadth. The garden-centre version was bred from just a few plants to enhance its looks and abundance of flowers. Genetic diversity exists only in the wild plants, and it’s this variety that helps keep the plants healthy and robust, safer from disease and more adaptable to change. With every plant lost in the wild, this diversity shrinks.

But wild plants are barely holding on. Ngutukākā survives only in a few clusters in the triangle between Hawke’s Bay, the East Cape, and Te Urewera—only 108 at the most recent census, down from 159 in 2007—clinging to steep bluffs or surviving only because they’ve been sequestered in fenced enclosures designed to keep out everything that would eat them. And it is almost everything. Slugs and snails devour small seedlings overnight. Hares and rabbits gnaw bigger plants back to a shredded stalk. Deer and goats love them. (Only possums, surprisingly, don’t like them.)

A relative of peas, kākābeak is one of the tastiest, most easily reached plants for introduced hoofed browsers. The plants have been forced out of all but the tiniest pockets of remaining habitat—often no more than a ledge on a cliff, where even the most adventurous goats can’t reach. But in these refuges, there are other hostilities: extreme rainfall and drought.

DOC lists ngutukākā as “nationally critical”—its highest threat category, at immediate risk of extinction in the wild. It is the only native plant for which DOC has a rescue plan, and this plan was recently reactivated, prompted by the drop in plant numbers. “The long-term plan is obviously to have self-sustaining populations,” says recovery group leader Paul Cashmore. But in the short term, the goal is to keep the remaining wild plants alive and to “hold the line”.

As the biodiversity ranger for Tairāwhiti, holding the line is one of Graeme Atkins’ jobs. The plants surviving in DOC reserves north and south of Tokomaru Bay aren’t fenced and, despite year-round pest control, goats make short shrift of any seedlings. Meanwhile, red deer, which arrived about a decade ago, are a growing menace. Over the past two years, the number of wild ngutukākā in the region has dropped from 60 to 24.

“The two reserves were the showpieces of our ecosystem restoration mahi,” says Atkins. Not any more. “The issue we now face is that we have run out of safe places for many of our native flora species, ngutukākā included.”

As part of a personal pledge not to let this plant go extinct on his watch, Atkins joined Mere Tamanui and other locals to establish the Tairāwhiti Ngutukākā Trust. The group’s aim is to propagate plants from wild seed and get the local community involved in looking after them. “No one benefits when it’s just hanging on a cliff and nobody gets to see it,” says Atkins. “How can you expect people to care for something if they’re not interacting with it any more?”Last winter, the trust planted 800 ngutukākā around three schools and marae, including 70 plants which now grace the waharoa and ātea of Pākirikiri, the main marae in Tokomaru Bay. Even Waka Kotahi NZ Transport Agency got on board with the trust’s restoration project and is now using wild-derived kākābeak seedlings for roadside plantings along the East Coast’s State Highway 35. Atkins and Uncle Bogs share a vision of berms erupting in red each spring.

In perhaps the most poignant symbol of restitution, Atkins shows me a strip of ngutukākā outside Hinetamatea, the wharenui of the marae at Anaura Bay, where local wild plants mingle with those grown from seeds returned from England (see sidebar), home again after a centuries-long tipi haere.

[Chapter Break]

For Māori, ngutukākā is a taonga species. It was cultivated, gifted and traded throughout the North Island, grown for its exuberant good looks and as a food source. It even brought tūī and korimako down to the flowers and into snares. “They’re pretty plants, but they served a practical purpose as well,” says Atkins.

For many marae, ngutukākā held symbolic meaning, embroidered in linen and painted or woven into kōwhaiwhai panels, says Tamanui: “That’s where a lot of our mātauranga Māori is stored.”

Hawke’s Bay farmer and naturalist Herbert Guthrie-Smith wrote in 1921 that kākābeak had once grown in great quantities near the top of Te Heru o Tūreia, a low mountain in the Maungahāruru Range—until the plants were devoured by cattle.

Te Heru o Tūreia, or the comb of Tūreia, is an important landmark for Ngāti Pāhauwera. (Tūreia is the ancestor who first held the mana over the region.) Long before Guthrie-Smith’s time, people treasured the ngutukākā growing on these cliffs. According to Ngāti Pāhauwera trustee Theresa Thornton, women from hapū around the mountain used to weave ngutukākā flower bunches in their hair and give plants to manuhiri guests to take back to their home marae. Te Heru is also where one of Ngāti Pāhauwera’s chiefs is buried.

“The colour all chiefs wore was red,” says fellow trustee Charlie Lambert. “The ngutukākā is a specific [kōwhaiwhai] pattern. It is a symbol of rangatiratanga for our people.”

Ngāti Pāhauwera’s gardeners have adopted ngutukākā, and the iwi is preparing for a goat-culling operation on the bluffs on Te Heru o Tūreia. “Te Heru used to be red with ngutukākā,” says Thornton, “so we’ve got to be part of the solution to make it red again.”

[Chapter Break]

For DOC ranger Alan Lee, replanting ngutukākā involves a helicopter and a double-barrelled shotgun. He’s helped to devise a method of stuffing cartridges with clay balls covered in seeds, then firing them out the open helicopter door. It’s accurate, he says, and lodges seeds in the soil of the bluffs, where they can grow without being disturbed. But it’s slow. A faster method is to toss clumps of hydroseeding fibre mixed with seeds, or even just handfuls of seeds, out the window over suitable habitat. Between all these projectile options, Lee and others have distributed more than five million seeds during three helicopter missions since 2015.

Nothing has sprung from the effort—yet. Kākābeak seeds can remain dormant for up to 30 years, and Lee says having seeds scattered around the environment is important because it tops up the seed bank produced by the few remaining wild plants. “If we don’t do this, then because the plants are so few and far between through that whole area, the seed bank would just slowly disappear,” he says. “Our chances of having a persistent population would be pretty low.”

[sidebar-1]

Lee has been looking after several plants that hang off boulders on top of a waterfall at Boundary Stream Scenic Reserve. He learned the hard way that, even with the best care and regular pest control, most seedlings don’t last very long. He was thrilled to discover 32 tiny seedlings under the fenced-in plants during New Zealand Geographic photographer Rob Suisted’s visit, but none of the seedlings were taller than about five centimetres. “I’m assuming most of them will either suffer from drought and die,” says Lee, “or get eaten by snails.”

[Chapter Break]

I’m looking across the Waiau River to the spectacular bluffs at the edge of Te Urewera, searching for a plant named after Willie Shaw. Back in 1983, botanist Shaw and his wife were scouting the area when they recognised the sheer cliffs as potential habitat for ngutukākā, and decided to climb up and sidle along to have a look. At first, they found nothing, but on his way back, Shaw caught a glimpse of red over his shoulder—a few remnant blooms on a kākābeak near the end of the flowering season.

Twenty-five years later, Shaw returned with his younger brother, Pete, and to their delight the bush was still there in “full bloom and absolutely spectacular”. It was catalogued as Willie’s Plant. They discovered another, smaller plant—Willie’s 2.

“After that, I spent a bit of time scuttling around and found one on a white slip, which we named Whiteslip, and another one on a bluff,” says Pete.

After Bluff and Whiteslip, subsequent searches found others—later named Edge, Pete’s Plant, and Vicky’s and Kevin’s—all clinging to small mounds of soil in crevices on cliffs. When I last visited the area in 2014, I spotted some of these plants through binoculars. This time, though, there’s nothing left.

“They’ve all died, mainly through drought,” says Pete. “Willie’s Plant was at least 25 years old, and when it was re-found, it stayed alive for another five years or so. Then it got clobbered in a snowstorm and never really recovered. It was the first to go, and then the others died off in various droughts following that.”

No wild ngutukākā survive in the Waiau catchment now. Pete’s foresight in collecting seeds and cuttings meant that each plant’s whakapapa continues. “Even though we’ve lost the plants in the wild, we still have captured that genetic material, which is just so vital to keeping the genetic diversity within the population.”

Just behind us, on the Maungataniwha side of the river, within view of where Willie’s Plant once grew, a fenced enclosure is now home to ngutukākā sprouted from lost plants. Among them is big-leaved Gareth, named after a young DOC worker who hung 40 metres from a helicopter strop to snatch material from a plant now dead in the wild. And there’s also Te Heru, descended from the plants that once grew on the cliffs of Te Heru o Tūreia.

These enclosures are part insurance policy, part intensive-care unit where each plant is regularly slug-baited, fertilised and protected from too much or too little sun.

James Powrie, a former commercial forester, is now the main caretaker of the seedlings. Now a consultant in forestry restoration, he soon realised that the kākābeak’s original habitat was so overrun with goats and deer that the plants had nowhere left to grow.

“They’re doomed in the wild,” he says. Instead, kākābeak needs new habitat. “The obvious places are the towns and cities, where there aren’t goats and deer wandering free.”

And so began the Urban Kākābeak Project in Napier, where gardeners grow plants with known genetic provenance from the region and return seeds to the project. Marie Taylor, who runs a native nursery in Napier, has already established living replicas of genetic lines of Hawke’s Bay ngutukākā. She expects all Hawke’s Bay wild plants—numbering fewer than 10 now—will be gone within five years, unless the rescue operation shifts gear significantly. “We need more money and more guns,” she says. The wild population is “in freefall”, and although the plants are checked regularly, there’s not enough action being taken to save them, says Taylor. Instead, they’re “being monitored into extinction”.

For Taylor, kākābeak is an indicator of bigger trouble in the forest. The bush in Hawke’s Bay is lacking in numbers of variety of species, she explains. “There are hardly any fully functioning forests in Hawke’s Bay. They’re all [going] downhill unless they’re deer-fenced.”

Taylor envisions a royalty system, with money from the sale of eco-sourced plants going back into conservation to fund their ongoing propagation and provide enduring protection for wild plants—making sure plants are cared for until there are again safe places in the wild.

Powrie agrees. “Ironically, it’s human intervention that brought the pests to New Zealand and resulted in the destruction of what was quite a resource of beautiful red-flowering plants covering hilltops,” he says. “It’s human intervention that’s actually going to ensure the survival of the plant as well.”