Kiwi – icon in trouble

Maori call them “te manu huna a Tane,” the hidden bird of Tane, god of the forest. Once they were so abundant that settlers complained their shrill cries kept them awake at nights. Not any more. Kiwi, the unofficial emblem of the nation, are losing in a tussle for survival within the very forests that were once their stronghold. But a concerted programme by biologists, wildlife centres and public-spirited citizens seeks to turn the tide for these Secretive and Peculiar birds.

second largest of the six living kiwi varieties. Groups of tokoeka regularly forage for sandhoppers and other arthropods on beaches around the island, stabbing their beaks into the sand in pursuit of prey. After such salty work, the birds can sometimes be glimpsed taking refreshment from the streams that spill out across the sand.

On the edge of a mountain plateau which rises like an island above the coastal forest of the Heaphy Track, I stand motionless, peering into the darkness through a pair of night-vision binoculars. Without them, I’m blind—even my companion, ecologist John McLennan, looks like just another piece of shrubbery. So my eyes are glued to this electronic peephole and the fluoro-green view it affords: a shimmering stage set of phantom trees and moths zipping around like kites in the wind.

As well as this expensive gadget, McLennan has brought something much less high-tech: a plastic shepherd’s whistle, which he wears around his neck. I watch him fish it out from under his jacket, take a deep breath and put it to his lips. The first couple of calls are misshaped, but he soon finds the right pitch.

Crrweeee! Crrweeee! Crrweeee! he repeats a dozen times.

There is a moment of deep silence, then comes the sound of rustling through the undergrowth. Something is coming towards us—at speed.

Into my field of view runs the oddest of creatures, a shaggy, pear-shaped ball of feathers propelled by large T rex feet, sniffing and snorting like an agitated hound. It stops to let out another battle cry—a penetrating shriek that makes you want to plug up your ears—then freezes to listen out for the intruder.

We hold our breaths against this fierce audio scrutiny, and soon, reassured of its dominance, the creature relaxes and resumes feeding. Its beak taps the way ahead like a blind person’s cane, and every few steps the bird augers it excitedly right up to the hilt in pursuit of a wriggling morsel. Now and then it pauses to blow the dirt out of its nostrils with a sharp sneeze. Then, with no more than a rustle of ferns, it vanishes, though for a while we can still hear it. Tap! Tap! Jab! Snort! goes the kiwi, the ghost of the forest.

Here, in the heart of Kahurangi National Park, the night still belongs to the kiwi. You can hear them calling across the glades: the shrill Crrweeee! of the male and the guttural reply of his larger partner, both ready to attack anything that blunders into their 25 ha territory.

“They fight like devils,” McLennan tells me. “Put two rival kiwi together and soon you may have only one left alive.”

Their combat is a furious kick-and-tear kind of karate, with high jumps and slashing blows with their sickle claws. Once their kingdoms are established, however, the birds usually resolve territorial disputes by vocal duels, avoiding border scraps altogether. This leaves more time for feeding—for sniffing out beetles or moth larvae from beneath clumps of tussock, or wrestling earthworms out of the ground.

“Some of the big native worms resemble a length of garden hose, with a diameter to match,” McLennan says. “They are powerful and reluctant victims, and often escape after a brief struggle. But once a kiwi gets a good grip on one of them, the tug-of-war can last for several minutes.”

defending territories which range in size from just a few hectares to over 100 ha. Loud cries-which can carry several kilometres assert a bird’s dominance in an area, and warn off intruders. If vocal threats are ignored, a full-scale fight can ensue, and the combination of sharp claws and powerful feet can tear an adversary apart.

The bird applies a steady strain and waits for the opponent to yield, because yanking it would tear the worm in two and shorten the meal. Some worms phosphoresce as they are pulled from the soil, illuminating the kiwi’s bill and face with an eerie light.

McLennan, who has been studying the lives of these nocturnal hunters for the past 15 years, says his most significant finding has not been about how they eat or fight, or where they sleep, but the simple fact that they are becoming increasingly thin on the ground.

“We revere and adore the kiwi as an emblematic figure in so many guises, but in the forest the real birds are experiencing not just a decline but an all-out population collapse,” he says. “The kiwi as an image and a name has suffered from chronic overuse. It has become too much of an icon and not enough of a bird. If we don’t wake up to this fact soon, within a few decades the icon will be all that’s left.”

[chapter-break]

Among the ratites, the group that contains the world’s largest birds, including emu, rhea, ostrich and cassowary, as well as the extinct elephantbirds of Madagascar and our several species of moa, the six currently recognised varieties of kiwi are the smallest and the most cryptic.

The name ratite, from ratis, Latin for raft, refers to the birds’ sternum, which is flat and raft-like, lacking a keel to which flight muscles could be attached. So, like all of their relatives, kiwi are permanently grounded. Their wings, atrophied into vestigial stumps and culminating in tiny cat-claws, inspired their generic name: the euphonious, if not completely accurate, Apteryx, meaning wingless.

But here the neat Linnaean taxonomy ends, because kiwi—a disparity not just among ratites but all other birds as well—stand alone in eccentricities of their anatomy and behaviour.

While other ratites thump the earth with their large, dinosauric feet, kiwi can walk almost silently, their loping trot muffled by fleshy footpads. They dig burrows like a badger, and their faces bristle with feline whiskers. They have distinct ears, and their shaggy plumage looks more like fur than feathers. More than one biologist has noted a rodent-like quality to the birds—they seem more rat than ratite.

Kiwi typically emerge from their burrows just after sunset and, like a dog, literally follow their noses searching for food. The long, flexible beak is equipped with a pair of sensitive nostrils at its tip—an adaptation unique to kiwi. Stabbed repeatedly into the soggy world of earthworms and grubs, this remarkable appendage serves as an olfactory underground periscope. In other birds, a sense of smell is of little importance.

While, for aerodynamic reasons, the bones of most birds are light and hollow, those of kiwi are heavy and filled with marrow. Kiwi skin is tough enough to be made into shoe-leather, and the body temperature, 38°C, is closer to our own than to the temperatures of most other birds, which are in the 39-42° range (peaking at nearly 45° for hummingbirds).

In many ways, the kiwi is remarkably unbird-like. So much so that zoologists, among them Harvard’s Stephen Jay Gould, have bestowed on it the status of “honorary mammal”—a title which alludes to the fact that prehuman New Zealand had no native terrestrial mammals except bats. In this mammal-free zone, kiwi are regarded as having filled an ecological niche elsewhere occupied by anteaters, hedgehogs and echidnas.

So unusual is the kiwi that when the first specimen skin arrived in England around 1811, it was considered a hoax on a par with the outlandish platypus; an unlikely anatomical hotchpotch skilfully stitched together by a clowning taxidermist. But then the early 19th century was a time when, in terms of biological discoveries, almost anything was possible. Only 28 years later, a single fist-sized bone fragment from the very same islands would convince the renowned comparative anatomist Sir Richard Owen of the existence of a large bird he called Dinornis, “the terrible bird.” Commonly, it would be known by its Maori name, moa, the tallest bird that ever lived, a flightless, totally wingless browser, and a neighbour of the kiwi.

locate their well camouflaged quarry. Tom Herbert, of the Department of Conservation in Trounson Kauri Park, has 40 kiwi tagged with radio transmitters to follow the health of the population in the 586 ha forest.

In 1813, George Shaw, the Assistant Keeper of Zoology at the British Museum, described as best he could the anomalous bird in front of him, and gave it the name Apteryx australis. The artist’s impression that accompanied the description showed a penguin-like creature with a Pinocchio nose—probably not a bad rendering considering that the only source of information was a dry, boneless skin.

Only later, as more specimens arrived, did it become apparent that the kiwi was neither a collector’s jest nor an evolutionary whim, and its posture and shape were corrected. In 1851, a live female kiwi was sent to London Zoo, where it laid infertile eggs and lived for more than 15 years.

As was the case with huia feathers, kiwi “fur” accessories became fashionable in Europe in the latter part of the 19th century, and thousands of kiwi were slaughtered to supply this trade.

The early colonists weren’t averse to tossing the odd kiwi into the cooking pot, though it was rarely a favourite repast. Charlie Douglas, explorer, surveyor and keen observer of nature, described how once, crossing a large swamp, he sprained his ankle and had to crawl for several days to reach his camp. Along the way he came across two kiwi in their burrow. “Being pushed with hunger, I ate the pair of them. Under the circumstances I would have eaten the last of the Dodos,” he related. They had an earthy flavour, he added, “like a piece of pork boiled in an old coffin.”

Apteryx must have been tasty, or exotic, enough to be served in country inns. Rudyard Kipling had one in Tokaanu, and thought it acceptable. Today, though the literal kiwi is off the menu, plenty of takeaway joints offer a burger by the same name, where it’s not the meat but the moniker you’re buying. In fact, everywhere you look you can see the nosy, amiable bipeds lending their name to every product under the New Zealand sun.

The only place you won’t see them—or, at least, not without difficulty—is in the wild. One reason is their increasing scarcity. Another is that kiwi are masters of camouflage and stealth. Their mottled plumage blends perfectly with the forest understorey, they often use a different shelter each day, and they dig their nesting burrows so long in advance that the moss and ferns re-establish themselves around the entrance, obliterating all signs of excavation. On leaving the burrow for a night of feeding, kiwi often mask the opening with deftly placed twigs.

The easiest way to view kiwi is to visit one of the 14 “nocturnal houses” dotted around the country. These establishments simulate night-time conditions so that visitors can see kiwi going about their activities during daylight hours. The Otorohanga Kiwi House and Auckland Zoo were the first to put kiwi on display, both in 1971. Prior to this, the only place in the world where kiwi could be seen in a nocturnal house was at the San Diego Zoo. Nowadays, some 80 kiwi (almost all of them North Island brown kiwi) are held by the New Zealand kiwi houses, and a further 36 birds are displayed by 11 overseas zoos.

Even in the dimly lit precincts of a nocturnal house it takes patience to spot the birds, which merge so perfectly with their surroundings. Multiply that difficulty tenfold if you are looking for kiwi in the forest. For the first five months of his study of North Island brown kiwi, John McLennan did not see a single bird. His tracking dog spent most of its time trying to get rid of its muzzle, while McLennan battled through the bush, night after night, finding only kiwi footprints. Finally, he managed to catch a young male in a pitfall trap.

It seemed a surprise for them both.

Yet this mastery of disguise has its drawbacks. If all the remaining kiwi suddenly disappeared, who but a handful of field biologists would notice? In fact, this is exactly what is happening. Kiwi are camouflaging their own demise.

[chapter-break]

When tane mahuta, the largest remaining kauri in the Northland forests, was still a seedling about 1200 years ago, there were an estimated 12 million kiwi in New Zealand, living in densities of up to 100 birds per square kilometre.

Even 100 years ago, the birds were still sufficiently numerous for one hunter, who captured kiwi for their feathers to decorate European hats and muffs, to admit to having taken 2200 birds. It was an indication of the perceived merits of native and introduced wildlife that the 1867 Animals Protection Act gave protection to exotic game animals but not to native birds. Some were later classed as “native game” to give them a measure of protection from hunting, but it was not until 1922 that most native birds were given absolute protection.

No one paid much attention to how kiwi were faring. Their cries were heard at night, they were protected by law and, unlike rarities such as kakapo, takahe, saddlebacks and black robins, they were widely distributed. It seemed ludicrous to think that they might become extinct.

forming when the first egg is laid. Invisible in this X-ray, but no less remarkable, is the fact that the egg is

65 per cent yolk, compared with 35-40 per cent in most birds.

But in the late 1980s, the Department of Conservation started to get a few disconcerting reports. Hunters and trampers were noting that kiwi sign and calls were missing from areas where, just a few years earlier, they had been abundant.

Results from a survey in 1992-93 of “kiwi country” were compared with results from a similar survey made by the Wildlife Service 20 years earlier, confirming that the ranges of kiwi were indeed shrinking.

By 1995-96, the full extent of the decline was becoming apparent: there were only about 70,000 kiwi left. One species, the little spotted kiwi—smallest and once apparently the most common—was already gone from the mainland, and populations of the others were melting away at a rate of six per cent a year.

Last century, settlers complained that kiwi kept them awake at night with their calls. Now people were again losing sleep over kiwi, this time trying to figure out how to halt the decline. One who endured more sleep deprivation than most was McLennan.

A keen outdoorsman, more at home in forest and mountains than in the lecture halls of academia, he paid his way through university by diving for paua and hunting white-tailed deer around the coast of Stewart Island. After completing his PhD (on the flocking behaviour of wading birds) McLennan turned his attention to the lonesome kiwi, partly because the nature of the birds struck a chord with his own, but also because kiwi—little studied, poorly understood, rarely seen—presented an exciting fieldwork challenge.

cases. Young birds emerge fully feathered and provisioned with sufficient yolk to sustain them for their first week of life. Thereafter they have to provide for themselves, for kiwi parents never feed their offspring.

His current study area is the 750 ha Puketukutuku Peninsula, which juts into Lake Waikaremoana, a misty, many-armed waterway lost among the thickly forested hills that constitute Urewera National Park, part of the largest remaining tract of beech forest in the North Island. To get there you follow one of the country’s longest unsealed roads—a windy, juddering drive from Murupara to Wairoa.

McLennan picks me up from the lakeshore in his battered aluminium runabout, which, he tells me, has clocked a mileage equivalent of the length of the Equator, and we plane across the corrugated water to the ranger’s but that has become his second home. Late in the evening, we motor to the study area. Some of the eggs are due to hatch any time now, and McLennan wants to check them. We walk for an hour along a narrow trail marked with tiny cat’s-eye reflectors, then settle for a long wait in the nook of a mossy stump.

The forest is so silent and still you can hear the leaves falling, but just after midnight there comes that unmistakable outburst of noise as if some playground bully were torturing a whistle with such force that the effort made him promptly run out of breath. This is the sound of a male North Island kiwi stating his territorial presence and announcing his departure for the night’s foraging.

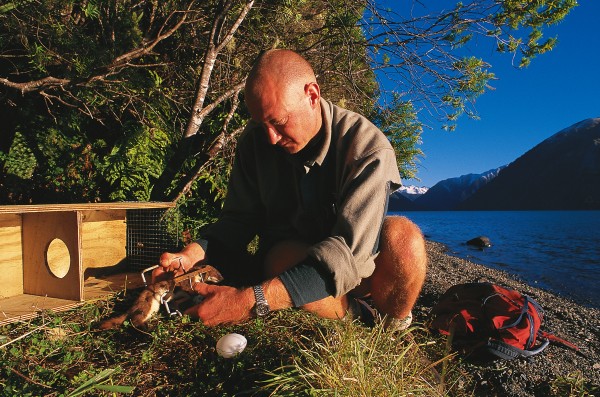

For us, it’s a signal that the nest is now vacant. McLennan leads the way down a steep gully, and in its bank finds the hidden burrow. An arm’s length inside is a fist-sized egg, and next to it something brown, round and softly spiky, like a baby hedgehog. A four-day-old kiwi chick.

Its beak is as long and as pink as a child’s finger, its feathers soft and moist and smelling of a rotting log. “There are few things in this world as beautiful as this,” McLennan whispers, cradling the chick in his large hands. “This is why I walk the forest for months. It is as though you were touching the soul of this land.”

The chick, soon drowsy to the point of nodding off, is the result of somewhat unorthodox parenting. Relative to their size, kiwi have one of the largest eggs of any bird, up to four times bigger than could be theoretically expected. The egg grows to constitute 15-18 per cent of the bird’s mass, filling up the female’s body to such a degree that she sometimes soaks her belly in puddles of cold water to relieve the pressure and rest the weight.

In most varieties of kiwi, the typical clutch is one egg, laid two to three weeks after mating. Only North Island brown kiwi regularly lay a second egg, two to fourder, though: its tummy, taut like a balloon, is distended with yolk, which will nourish it for the first week of its life. Kiwi eggs are 65 per cent yolk, compared with the 35 to 40 per cent typical of most birds.

Within a few days, the chick, which is born fully feathered, begins to venture outside the burrow, and by day 10 it is out for most of the night. Somehow, it knows all about the business of being a kiwi, of finding the right food and shelter. Somehow, it knows that its best chance of survival is eating lots and growing fast. What it probably doesn’t know is that almost inevitably it will fail.

the stoat, a fierce predator which has no trouble despatching young kiwi that weigh even four or five times

its own weight. Only when birds have attained a weight of 1200 g-which takes at least six hazardous

months-do stoats leave them alone.

McLennan and his colleagues in the Kiwi Recovery Programme—a kind of war council formed in 1991 to combat the birds’ decline—have found that 95 per cent of kiwi chicks die within the first few months of their life. Only one per cent survive into adulthood.

They have also found the primary killer.

[chapter-break]

New Zealand was once an island Eden, an ark that broke off the ancestral supercontinent of Gondwana and never quite arrived anywhere, but stayed afloat in the South Pacific, becoming a world unto itself.

There are several such arks anchored around the planet—Mauritius, Hawaii, Galapagos—which, though distant and distinct from one other, all have one thing in common. Life on them evolved in isolation from a pool of original stowaways, and subsequent immigrants were few, usually birds and insects. According to eminent American naturalist Edward 0. Wilson, such islands are the key to our understanding of how nature works, because the links between species are simpler and clearer than in continental ecosystems. The ecological tapestry of islands is woven more coarsely and contains fewer threads.

In 1967, Wilson and mathematical ecologist Robert MacArthur published their findings in a book entitled The Theory of Island Biogeography, which has become a canon of evolutionary biology. Each island, they proposed, could sustain only so many species, so if a new species arrived and colonised the island, an older resident would be forced into extinction. The arrival of human settlers to such islands—along with the entourage of vermin that accompanied them—typically unleashed a wave of extinctions and set the ecological tapestry unravelling.

In New Zealand, the avian fauna was decimated by a deadly combination of rats and mustelids. Rats (three species) accompanied Polynesian and European immigrants. Mustelids (also three species) were liberated in one of history’s most bungled attempts at biocontrol. From the early 1880s, stoats, ferrets and weasels were imported to contain the rabbit population explosion, but from the moment they arrived they took an unhealthy interest in our birds.

Chief villain among the mustelid trio is the stoat. Not only is it a nimble climber and a long-distance swimmer, it is also a far-ranging and efficient hunter. It also has a tendency to kill more than it needs, which is why a stoat breaking into a chook-house is like a visit from the angel of death. The stoat’s genetic programming impels it to cache food for a heavy winter, which, in New Zealand, invariably never arrives.

something like 25 per cent of their body weight in food every day. Traps baited with eggs, fat or meat are used to reduce their numbers but, as the young can disperse very widely, it is an unremitting task, here tackled by Darren Peters, working on a mainland island project at Lake Rotoiti.

At the same time that mustelids were being encouraged to proliferate here, in Britain—a country of similar size—there were some 23,000 gamekeepers employed to exterminate them. Today, in both countries, they endure, due in the main to their dispersal abilities, combined with certain paedophiliac tendencies. A male stoat will mate not only with a female that has just given birth, but also with all the female baby stoats in the den, even if they are still tiny and blind. This impregnation is like a pill with a delayed effect, so, leaving the den, the young already carry within them the seed of the next generation. And because stoats are aggressively territorial, the young have to seek out their own place, fanning out far and wide, emissaries of menace—agile, tenacious, fearless.

“When a stoat looks you over head to toe, you know it’s calculating, sizing you up,” a possum hunter once told me. “If they were this big”—he pointed at his dog—”there wouldn’t be too many people around!”

Indeed, the stoat is cunning enough not to attack prey that it cannot handle. An adult kiwi could kick one to shreds, but a gawkish chick makes an easy meal. The predator knows its match precisely, and for a kiwi it is about 1200 g—four to six times the body weight of a stoat. Reaching this weight usually assures the bird’s survival, but it can take 40 long and perilous weeks.

Creating a stoat-proof enclave for kiwi was a priority for McLennan, and he chose Puketukutuku because, like a fortress, it could be easily defended. Across the narrow neck of the peninsula he ran a double trapline, and then, with the help of a professional hunter, eradicated all the stoats inside the enclosure. He thus effectively turned the peninsula into a predator-free island, a kiwi haven. In 1998, all of his chicks survived.

[chapter-break]

The concept of island sanctuaries is not new. In 1894, Richard Henry masterminded the transfer of some 750 kiwi and kakapo to Resolution Island, in Fiordland. But he underestimated the enemy. Stoats swam across from the mainland, and 14 years of work was undone.

Despite that setback, many of our offshore islands have now been turned into refuges for species that elsewhere are either extinct or extremely rare. Some of them were natural sanctuaries on account of their distance from the mainland or their inaccessibility, and only needed to have landings strictly controlled. Others, in the fashion of McLennan’s peninsula, have had to be restored through painstaking trapping of noxious animals and subsequent vigilance against reinvasion.

Whatever their past, these islands now serve as insular aviaries, genetic safe houses which offer endangered species an evolutionary second chance, the opportunity of an assisted comeback.

For kiwi, there is no more telling example than Kapiti, a sliver of mountainous, rain-soused land lying off the west coast north of Wellington.

Former home of Te Rauparaha, then the site of a whaling station, then a ne’er-do-well sheep farm, in 1897 the island was turned into a wildlife sanctuary. The cleared forest slowly grew back, and the resident caretakers methodically eradicated the vermin. Between 1980 and 1986, 22,500 possums were removed from this 2000 ha island, and a week before my visit the reserve was officially declared rat-free.

fashion houses with feathers for kiwi muffs.

Kapiti, now aflutter with birds unseen in most parts of the country, is also home to the largest population of little spotted kiwi. The birds are thought to have been brought here from the South Island in 1912 or 1923, when it became clear that the species was not going to survive on the mainland. In recent years, “little spots” have filled the island to capacity. There are more than 1000 resident birds, and a number of pairs have been shipped to other islands such as Hen, Tiritiri Matangi and Red Mercury, where they have founded healthy and self-sustaining populations.

Island reserves have an unparalleled educative role, says Peter Daniel, a ranger who has just retired after 26 years of Kapiti custodianship. “In our relationship with the natural world, there is an odd phenomenon which I call a law of diminishing expectations,” he told me. “As consumers, we insist on sleeker cars, faster computers and better medicines, but when it comes to nature, with each generation we expect to see less and less. Our children will expect even less, and their children won’t know what to expect. That’s why we desperately need places like Kapiti. They remind us how rich our native fauna once was, and how rich it can be once again.”

You can glimpse these riches in a grand setting in 586 ha Trounson Kauri Park, north of Dargaville. Here, the concept of island refuges has been transplanted to the mainland.

Alan Saunders, head of the Department of Conservation’s mainland islands project, and a man of irrepressible enthusiasm, explains: “Until recently, New Zealand has been an extinction hotspot, on a par with Hawaii and Mauritius. But the tide is slowly turning. We are now moving from protection of single species to restoration of entire ecosystems, because, as the offshore island experience shows, if you look after the habitat and if you remove some of the alien predators, the birds and other endemics will take care of themselves.”

“Kiwi are the indicators of our progress,” ranger Tom Herbert told me in Trounson. “Since we began our trapping programme in 1996, their numbers have reached over 200—a dramatic increase.”

Twenty kiwi per sq km (one per 5 ha) is a typical density for kiwi in Northland, but in one or two places they reach a bird per hectare. But despite the relative abundance of birds in Trounson, you could walk through the forest all night without finding one. In the kiwi’s sensory world we are the blind, blunt-nosed pachyderms, and that’s why Herbert relies on the cold, wet schnozzle of his Labrador, named Gemma.

Herbert is a Maori from Murupara, on the edge of the Ureweras, and he walks through the forest with natural ease, hopping from one mossy log to another, hands in pockets, endlessly conversing with the dog in a language only the two of them can understand. He has long, greying hair gathered in a pony-tail, and the same proud bearing you see in Goldie’s portraits of Maori warriors—an apt similarity considering that he, too, is fighting a war.

Though to a casual visitor Trounson is a paradise restored, with a wide boardwalk snaking among the kauri like an elevated bush railway, behind the scenes the park is a killing field. A 100-metre-square grid of trails has been imposed on the entire forest, and every junction is armed with a trap. Rats, mustelids and feral cats die there by the dozen; possums have been eradicated already. The maintenance of the grid is a full-time job, Herbert says, but the results are worth the effort. Such is the price of ecosystem restoration, the price of saving the kiwi.

“My dream is to extend the same regimen to the Waipoua,” Herbert says, referring to the 9105 ha kauri forest north of Trounson, where Tane Mahuta stands. “I’m sure this can be done. There is strong interest in the community. People are keen because plenty of jobs could be created in the process. If we could only get the money to fund such a project, the kiwi there could be as thick as the kangaroos in Oz.”

[chapter-break]

If alan saunders could have his way, there would be only three mainland islands in New Zealand: North, South and Stewart. As it is, laboriously restored fragments of native habitats, though splendid, exemplary and loud with forgotten bird song, are only micro-scale experiments—carefully tended gardens in a jungle of weeds.

Despite the odds stacked against them, kiwi still survive in the “weeds.” Reasonable populations have been found in pine forests, for instance. Hugh Robertson, director of the Kiwi Recovery Programme, speculates that kiwi success among pines may be due to lower numbers of mustelids: “There are fewer edible seeds and fruit in pine forests than in native bush, so rats and mice are less abundant. Since small rodents are the main prey for stoats and ferrets, we suspect that their numbers are reduced in exotic forests, and this may allow kiwi to breed more successfully.”

Waimarino Forest in the central North Island, Tairua Forest on the Coromandel Peninsula and a number of pine forests in Northland all support significant populations of kiwi, but the birds are absent from Kaingaroa, south-east of Rotorua—perhaps on account of its mineral-deficient pumice soils.

In pine plantations, farm woodlots, even in gorse and scrub on the outskirts of towns, wild kiwi turn up in surprising numbers in Northland, resolutely surviving but usually glimpsed only in adversity. An unchained dog brings home a kiwi carcass, a possum trap catches what it’s not meant to, a farmer sets fire to a useless piece of scrub and finds it alive with birds, a lawnmowing contractor hits a roadside stump, unearthing a two-egg burrow and sending a kiwi bolting for cover.

The initial reaction is often one of astonishment at the very existence of kiwi in such close proximity to human habitation. This may give way to remorse and perhaps a pang of compassion. With luck, the survivors—the injured, the lame, the traumatised—are spirited off to a bird rescue centre. In Whangarei, they are more than likely to end up on the operating table of Robert Webb.

For the past 30 years this former truckdriver, has been running a Dr Doolittle kind of surgery, incubating abandoned eggs, nursing back to health up to 750 native birds each year. It has always been a shoestring effort, run on donations and community sponsorship. Consequently, the holding pens are made of salvaged plywood, with old oven grill trays for doors. The birds’ bedding is shredded paper donated by a local document destruction company, and the operating table is an architect’s drawing board.

More than just a self-trained avian paramedic, Webb is also an ardent advocate of hands-on kiwi experience. He thinks nocturnal houses are contrived and unnatural. The birds in them behave so differently from their usual selves, he says, you might as well be looking at a stuffed museum exhibit.

“If people can’t see the real thing, why should they care about saving them?” Webb asks. “There are enough injured or unreleasable birds around, and you can easily train them so they feed in the daytime, so why not make them the ambassadors for their kin? Because when you watch them up close, when you’re able to touch them, they touch something inside your heart. Make you want to do something about their fate.

“Come on, I’ll show you something.”

From a box curtained with a towel he lifts out a brown kiwi and places it on the lawn. Initially, like any wild kiwi I’ve seen in the daylight, Snoopy looks dazed, squinting in the light and apparently grumpy at being so rudely woken up. But suddenly his confusion turns to excitement, then to greed, then to outright gluttony. The lawn around him, freshened by the morning dew, is alive with earthworms, fat as milkshake straws, long as shoelaces.

Lost sleep quickly forgotten, Snoopy digs in with a fury, plucking worms out of the ground with swift and deadly accuracy. A tweezering nip of the beak, a slow withdrawing pull, a backward flick of the head. Gulp! A quick nose-clearing snort, then another deep stab. Puuuuuuull. Gulp!

[Sidebar-1]

What McLennan has only occasionally glimpsed during a decade and a half of intensive research, what Peter Daniel saw only once in 26 years on Kapiti, Snoopy is performing on cue, no more than a couple of metres from my face. “No animal will feed if it’s stressed,” Webb tells me. “Is he stressed? Look at ‘im. If he was any more relaxed he’d fall over.”

Which for Snoopy is a constant possibility, considering he has only one leg. Eight years ago a gin trap near Kaitaia took the other one, and that’s how he found himself in Webb’s care. A local orthopaedist designed a prosthesis, but the stump festered from chafing, and Snoopy had to learn to go without it. His toes turned inwards, his balance realigned, and now he hops about like a tail-less kangaroo, only occasionally using his beak for a crutch.

This endearing invalidism has turned Snoopy into a Northland celebrity with a thick file of newspaper clippings to his credit. He is a regular visitor to schools, “rest homes and public meetings, where Webb spreads the word about the plight of the kiwi, campaigning against gin traps and uncontrolled dogs. “Once I took him to a conference of the Royal Foundation for the Blind,” Webb tells me. “They could touch him, and smell him, and feel the shape of his body. Their faces spoke a million words.”

edges of streams and even in the water.

His attention drifts back to Snoopy, who is still gobbling worms as if there was no tomorrow. “He must get all his liquid out of these worms,” Webb says, nodding at the bird. ” In eight years I’ve never seen him drink.”

The thing about kiwi, Webb tells me—North Island browns, at any rate—is that they are extremely unfussy birds. They don’t need to be put on a conservation pedestal, they don’t need national parks or reserves. As long as there is food and shelter, they will live on the most marginal land, in bracken, in gorse even. They will readily live with people, if only we choose to live with them.

On the surface of it, there seems to be no reason Kiwi and kiwi should not be able to accommodate each other’s needs. “The birds are born survivors—tough, adaptable and resilient,” says McLennan. “They can live almost anywhere. They are breeding machines, producing those huge eggs with the consistency of battery hens. All they need is some peace during the first few months of their life, because at the moment, the stoats just wait for the eggs to crack open so they can kill the hatchlings. But take the stoats away, and seeing a kiwi picking worms out of your vege garden at night might not seem like such an impossible dream.”

McLennan’s dream invariably relates to the kiwi that makes the gloomiest statistics and the loudest headlines: the North Island brown, the most common yet the most endangered species. In the areas occupied by North Island brown kiwi, several part-time advocates for the birds are employed by the Kiwi Recovery Programme. Adele Smaill’s beat is the Coromandel Peninsula, where her job is to raise public awareness of kiwi. She speaks to schools, community groups and farmers, appears at fairs—does anything, anywhere, to alert people to the presence of kiwi and how they can be helped.

Encouraging residents and holidaymakers to control their pets is an important part of Smaill’s brief. “I suggest that people do not buy bird dogs or hunting dogs such as Labradors and terriers as pets,” she says. “We are also working on a programme to train dogs not to follow the scent of kiwi, and are having some success. Kiwi have a strong smell to a dog, and represent a tempting target.” In 1987, a single German shepherd destroyed as many as 500 kiwi in Waitangi State Forest—half the resident population—during a six-week killing spree.

a white kiwi on Little Barrier Island is disturbingly visible in the camera’s flash.

Dogs are not the only problem pets. Cats gone feral are a menace, and roaming domestic cats can be, too. Ferrets, or fitches, sometimes billed as “pets for rebels,” are lethal to kiwi and other birds.

Smaill also gets involved when exotic forests are to be logged. She says that kiwi can survive logging surprisingly well, as long as there are adjacent unlogged blocks for them to migrate into. By juggling what blocks are logged when, forest managers can minimise the disruption.

But the survival of the kiwi is not just about helping any one species cope with the immediate threats confronting it, but retaining the long-term viability of all kiwi species and races in their respective habitats—a complex proposition, considering that there are still birds about which very little is known.

On the slopes of the Haast Range, in a remote corner of South Westland, there lives a kiwi as elusive as the Himalayan snow leopard. In early spring, before the snowmelt began swelling the rivers, I travelled up the Waiatoto valley with Rogan Colbourne, a Department of Conservation scientist with the Kiwi Recovery Programme. We jetboated up a twisting vein of greenstone water born on the flanks of Mt Aspiring, slaloming through countless snags and sunken tree logs, to a forest camp at the foothills of the range.

Over the past 20 years, Colbourne has worked with all kiwi species and their key populations, and as we set out on the first of our patrols he shares with me some of his hard-earned observations. Kiwi, for example, are strong, if reluctant, swimmers. Because they are so heavy, and quickly become waterlogged, only the tops of their heads and backs show above the surface. This gives them a clumsy, sinkingtea-kettle kind of look, but below, those huge drumsticks are kicking hard, so kiwi can make good headway even against a moderate current. One bird is known to have crossed the Whanganui River twice.

Pound for pound, Colbourne tells me, the little spotted kiwi are the most vicious and bad-tempered. They have the sharpest claws, and use them liberally. All kiwi will put up a fight when cornered, but Stewart Island tokoeka—as large as great spotted kiwi—are particularly notorious. “When you try to get them out of their burrows, they back up against the wall of the burrow and use their feet and claws like hammers. You’re lying there with your hand down the hole, and the earth underneath you shakes as if there was a sub-woofer buried there. Oomp! Oomp! Oomp! You have to synchronise with that rhythm and grab them on the off-beat!”

Colbourne has also gathered a lot of information about egg incubation and hatching. Kiwi were once thought to he among the few birds that don’t turn their eggs during incubation, but Colbourne convincingly dispelled that myth. He replaced an infertile egg with one equipped with five temperature probes. The adult bird never noticed the difference, and continued to incubate the electronic egg. Colbourne found that during incubation the temperature between the warm top and the cold bottom varied by as much as 10°C. The pattern of temperatures recorded by the probes showed that the bird must have been diligently turning the egg.

Equally revealing have been his insights into the social dynamics of kiwi families. Among the North Island browns, the male carries out all of the incubation of the eggs, leaving only to go feeding for a few hours each night. After hatching, chicks are often accompanied by a parent for a week or two, and may even share a day burrow with their father. After a fortnight, however, the youngsters are given short shrift.

Little spotted kiwi behave very similarly to North Island browns, but the parents allow the young to remain in their territory for up to a year. Young Okarito brown kiwi remain with their parents for at least nine months.

Among the Okarito and great spotted kiwi, the females play a much greater role in the incubation process, regularly taking turns on the egg. In all species of kiwi, brooding males develop a bare brood patch on their chests and bellies to better transfer body heat to the egg. Female Okarito kiwi also develop this patch. When both sexes incubate the egg, it stays warmer, and hatching is typically more rapid-65 to 70 days. The reason the North Island

several years and even help to incubate their eggs. This arrangement gives improved safety from predators (while there are no mustelids on Stewart Island, there are large numbers of feral cats) and also saves juveniles from blundering into foreign territories—for in places where predator numbers are low it is another kiwi that is a chick’s greatest enemy.

“It’s not just that the resident birds kill the intruder,” Colbourne says. “They feel obliged to tear and shred and pulp it and stomp it into the ground until it’s all mince and feathers.”

Ah, kiwi, our cuddly and comical national mascot!

Kiwi are not entirely antisocial, however. Male and female maintain a pair bond that lasts for years, if not life, although they do not necessarily cohabit. Often a pair jointly occupy a territory which contains hundreds of burrows, but share the same burrow only 40 per cent of the time.

Calling seems to play an important role in kiwi society, both to delineate territories and to identify individuals. In the early 1980s, Rogan Colbourne, along with radio’s “Bug Man,” Ruud Kleinpaste, made an extensive study of kiwi in Waitangi State Forest. They found that males, the more territorial gender, made 75 per cent of calls, especially during the early part of the breeding season. If two birds ended up close to each other on the edges of their territories, a vocal battle usually resulted, but not normally fisticuffs.

The male and female calls are quite different. The male North Island brown emits a whole string of brief shrill cries (up to 40) that may run over 30 seconds or longer, and his beak is wide open and pointing skywards while he sounds off. His cry may carry for up to a kilometre.

Female calls are quieter and hoarser—those of the North Island brown have been likened to the heaving noise a cat makes before it vomits! Calling is concentrated in the hours following sunset, and is more regularly heard on dark nights.

In their study, Kleinpaste and Colbourne noted quite a vocabulary of sounds among North Island browns. Members of a pair traded contact calls, there was a sniffling sound which accompanied feeding, and nasal grunts were exchanged between feeding pairs. Mewing and purring sounds—the latter carrying for up to 50 m—were used by courting and mating birds. Sounds associated with aggression included hissing, bill-snapping, squealing and growling.

Compared with the other varieties of kiwi, almost nothing is known about the sociology of the Haast tokoeka, the bird Colbourne and I are scouting for. Interactions between birds are rare, because they have huge territories. In a long day’s work of needling our way among giant trees laced up with supplejack and silenced with moss, we barely cross from one kiwi fiefdom to the next.

Finally, a radio signal leads is to a burrow, and in it—surprise!—one egg and two birds. We leave them to their incubation. Another burrow is too deep for Colbourne’s articulated peep-in mirror. Night is falling, and I still haven’t been able to get a good look at the bird I’ve come so far to see.

Again, it is the canine that saves the day. In a ferny hollow under a log, Oscar, Colbourne’s black Labrador, sniffs out a 2.9 kg female—unbanded, untagged, wild. It is unlike any kiwi I’ve ever seen, with whitish feet, a short beak and a thick, downy coat the colour of a red deer.

The Haast tokoeka is our only alpine kiwi, and numbers no more than 250 birds. Prior to making this trip to the Waiatoto, Colbourne surveyed the Haast Range population, which spills into the neighbouring valleys, and was surprised to find that, at the end of the winter, the birds were fat and healthy and nesting in rock crevices under half a metre of snow. He thinks that this preference for the harshest of habitats is due to the profusion of invertebrate life to be found there—weta, land snails, weevils.

Even during heavy winters the sun warms the rocks, creating miniature nunataks, and the kiwi probe around their soft peripheries for plentiful and comatose insects. Life in the fridge can have its advantages—keeping the food fresh and the predators at bay—just as long as you can fight off the cold. Appropriately, the Haast tokoeka is as fluffy as a malamute husky.

[chapter-break]

Back in our camp that night, under a tarp stretched among the trees, in the pale yellow light of a gas lantern, I ask Colbourne the inevitable question: beyond the eco-gloom, beyond the sound-bite statistics, what is the real situation with our national bird?

“They are certainly in trouble, but not all and not everywhere,” he tells me. “The great spots in Kahurangi, the Paparoas and around Arthurs Pass are holding their own. Just. The little spots are safe on offshore islands—we could easily crop 100 chicks every year and transfer them, if there was somewhere else to put them. The Stewart Island population of the southern tokoeka is the strongest and the most dynamic. The call counts there peak at 60 an hour, and we estimate 20,000 birds.

“The Okarito browns and the Haast tokoeka are the most vulnerable, because there are so few of them. But Okarito has the most intensive recovery regimen in the country, and the birds are starting to come back. We are now trying to set up a similar system here, in Haast.

“The North Island browns are definitely the worst off. They’re the media stars of the avian apocalypse. There are 30,000 northern brown kiwi—say, 15,000 pairs. Each pair is capable of producing up to four eggs per year, but being conservative we calculate they can bring up only two chicks. That’s 30,000 new birds, and almost all of them die every year due to predators. At the moment, all we can do is protect selected populations in their representative areas, in mainland islands, until a large-scale solution for controlling mustelids is found. When the predators are dealt with, kiwi will bounce back like rabbits. With just one year’s recruitment of juveniles their population could double. But for now, we’re just buying time.”

Operation Nest Egg, initiated by DoC in 1995, is another way of buying time—and giving ailing kiwi populations a much-needed boost. The programme involves collecting eggs from the wild, hatching them in incubators (at Auckland Zoo, Rainbow and Fairy Springs in Rotorua and Westshore Wildlife Reserve in Napier), rearing the chicks to a size at which they can look after themselves, then releasing them back into the wild. Through Operation Nest Egg, Okarito brown kiwi numbers have increased from 140 to 160, and several populations of North Island browns are also benefiting.

One problem is that it costs about $1000 to captive-rear a kiwi chick to the right size (six to nine months old). A new approach just being evaluated is to transfer two-week-old captive-reared chicks to predator-free islands where they can feed themselves. Once big enough to fend for themselves, they would be released in mainland forests to continue their adolescence, for they are not fully grown until about two years of age. Two such island creches are being trialled: Motuora Island in the Hauraki Gulf and Motuara Island in the Marlborough Sounds.

A solution to the problem of predators in mainland forests is unlikely to come in the form of a miraculous cure—a onceand-for-all ecological cleansing. “We will never get rid of all the mustelids. They are just too cunning and too numerous,” says Elaine Murphy, DoC’s predator scientist in charge of $6.6 million recently allocated to stoat research. “Their control will always be a matter of continuous maintenance, like trimming back the ever-encroaching weeds. All we can do is significantly curb their numbers, to give the birds a more even break and rebalance the predator-prey equilibrium. Only then will the two be able to coexist.”

Coexistence does not seem an impossible hope. Already, in Trounson, Tom Herbert tells me how he was once radio-tracking a kiwi, and the signal took him straight to a stoat den lined with bird feathers. “My heart sank,” he said. “I thought I’d be looking for a transmitter lying on the ground, but no. The kiwi burrow was on the other side of the same patch of pampas grass, and in it the bird was fast asleep. She had bite marks all over her beak. You could see that they had had a scrap, but she wasn’t about to give in. It was her burrow, and she was staying.”

[chapter-break]

From haast, I drive up to the glaciers, to the block of land between the Waiho and Okarito Rivers. I want to walk in the coastal forest at night and listen out for the rarest of our kiwi, the Okarito brown. There isn’t much hope of hearing them, I know, because the night is bright, near the full moon, and that usually puts a damper on kiwi vocalisation. But I continue to hope for something—a call, a glimpse, an assurance that they are out there.

They don’t call. I walk quietly among the moonlit trees, hearing nothing but moreporks and frogs, and pondering the arithmetic of extinction.

Suddenly, there is a rustle in the ferns, then a dog-like snuffling, and out of the forest, across a small ditch and on to the trail hops a familiar hunchbacked figure.

This is not the all-out charge I experienced in Kahurangi, but more the stop-go approach of a puppy, tentative yet uncontrollably curious. It moves towards me with a series of jolty, patting footfalls, freezing, craning its neck, sniffing the air, taking a few more steps.

Both its legs are banded—they flash with strips of reflective tape like the heels of a night jogger. Its beak, that multipurpose tool—a drill, a prod, a hoe and a pair of tweezers all at once—is soiled, and crumbs of dirt cling to its whiskers.

Now it is standing at my feet, the rarest kiwi in the world, touching me with its beak, examining me as a doctor would with a stethoscope. I melt into this magical moment of communion with the ghost of the forest, and feel my throat knotting up as I remember what McLennan said about the soul of the land and how it touched his own.

Gemma, in Trounson Kauri Park. If we can control introduced predators, our

much-loved and highly adaptable national emblem could stage a comeback in the next century.

Suddenly, the little rascal jumps up and kicks me!

It is a kangaroo kind of kick, with a catlike scratch, as feeble and experimental as the bird is young, but the attitude is there already, and the message is clear: “This is my turf. Hop it!”

I take heed. The bird, I learn later, is one of the new generation of kiwi, hatched and brought up in captivity and released back into the wild. It has obviously made the transition successfully. It found, claimed and defended its territory—no mean feat in this tough neighbourhood. It was curious and brave, streetwise and assertive; it stood its ground.

What better creature could we have chosen to symbolise us? More importantly, what is such a creature worth to us, because its survival is now largely a matter of money and political goodwill?

Last year, the Royal Forest and Bird Protection Society launched a “Kiwis for kiwis” initiative, aiming to raise $10 million a year over the next decade and drum up some solid political support for the cause, in order to create at least ten 10,00020,000 ha kiwi zones—an archipelago of large mainland islands.

Although funds for this ambitious project have not so far been forthcoming, a more modest project on the eastern side of the Coromandel Peninsula offers a portent of hope for kiwi.

On 800 ha of scrubby farmland, conservation estate and council land at Kuaotunu, a society of 450 concerned locals has established Project Kiwi, employing hunter and trapper Lance Dew to kill pests which threaten kiwi chicks and other wildlife.

Possums have already been cleaned out of the area, and stoats are becoming rare. The project has been running for four years, and over the past two, kiwi chick survival has risen from five per cent to 87 per cent. Some 50 kiwi—about 20 of them radio-tagged—live in the plot, and plans are afoot to extend the protected area to 2000 ha.

The project has not been without its difficulties, especially a dearth of funds. Dew, a no-nonsense Kiwi bloke, comments: “The really committed supporters haven’t been the greenies, but the shearers, the dairy farmers, the pig hunters—people who know about the land and are concerned that there mightn’t be much to show their kids if we don’t get off our backsides and do something.”

Project Kiwi is an indication that ordinary New Zealanders are willing to take matters into their own hands to help save the national bird, and that dedicated amateurs can achieve worthwhile results.

[Sidebar-2]

With more folk rooting for the kiwi, perhaps its haunting cry can once more echo across our land of an evening, reminding us that behind the symbol is a real—albeit most unusual—bird.