Coast. Country. Neighbourhood. City

Editor Michael Barrett refers to Coast. Country. Neighbourhood. City.—a compendium of projects by landscape architects Isthmus Group—as a “mix-tape”. And at one level it is. The 25 projects, mostly designed over the past decade, are loosely grouped according to the categories in the book’s title. Geographically, they range from the Mokihinui Gorge in the South Island to the Puketoi Range east of Dannevirke; and from Wellington’s Oriental Bay to Achilles Point in Auckland. The type of project is equally varied: from pathfinding a 200-kilometre transmission line route to marshalling evidence against a proposed new power-generation dam; and from designing a coastal walkway on the rim of the storm-swept Tasman Sea to seeding a new suburb on Auckland’s upper harbour.

What rescues Coast from being a 450-page CV—albeit a beautifully designed and presented one—is the attention it gives to the philosophical underpinnings of the projects. In doing so, it becomes a meditation on how, as New Zealanders, we might best interact with the land, and through the built environment express and reinforce our sense of identity and community. It encourages, in Barrett’s words, “deep thinking about the nature of place”.

Formed in 1988 by four graduates fresh out of Lincoln University, Isthmus Group from the outset challenged the status quo. Not everyone was impressed. The New Zealand Institute of Landscape Architects fretted about the potential damage to what was still a young profession, and dashed off a letter suggesting that they cease practice and find work elsewhere.

As Jacky Bowring of Lincoln University says in an introductory essay, intervening in the landscape is not something to be undertaken lightly, and nor should it be done reflexively.

“As we are bombarded by the global flow of ideas through the internet, films and television, it becomes easy to mimic the look of other places. Pinterest boards become a mélange of placeless, cool things to be applied anywhere,” she writes.

But nor should design succumb to a cloying and sentimental localism, which cynically appropriates and commodifies the characteristics of a region and sells it back to the people who live there.

Coast testifies to the tightrope Isthmus walks, taking the best from international practice and incorporating it in design thinking that is sensitive to the natural, social and historical specifics of a site. Bowring offers a name for the process—Critical Regionalism. Allied to this is a desire to undercut the dominance of visual culture which, Bowring suggests, floods the world with seductive images of disembodied “perfect” places. By constructing pathways, structures and environments that expose people to the tang of a salt marsh, the full fury of a Tasman gale, or the vertiginous thrust of a cantilevered viewing platform, designers can accentuate the truly local.

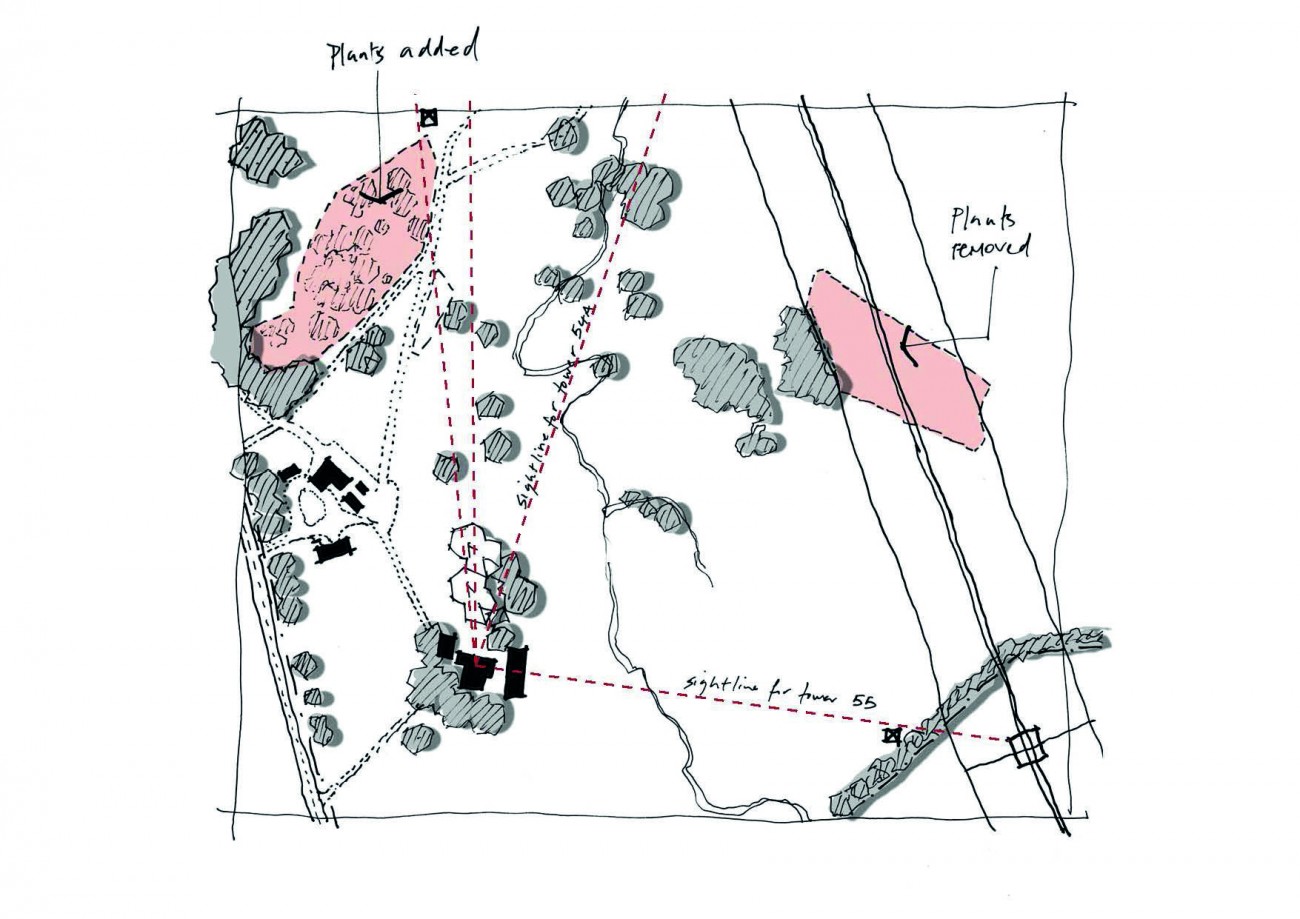

Transpower’s project to build a new 400-kilovolt transmission line from Whakamaru, north of Taupō, to Auckland presented unique challenges. The line, intended to assure security of supply to the country’s largest city, and to tap growing electricity generation from renewable sources in the central and lower North Island, involved figuring out the best way of placing 426 towering pylons and monopoles on a route stretching almost 200 kilometres. Isthmus was under no illusions that it could win the thanks of property owners anywhere along that route. Coast reminds us that the Dutch eventually came to terms with similar intrusions of technology (windmills) in their own landscape, thanks in part to sympathetic depictions on canvas by Rembrandt, Vermeer and others. But short of employing the Icelandic proposal of transforming power pylons into monumental striding figures of lattice and wire, art was unlikely this time to come to anyone’s aid. The 60–70-metre-high pylons were always going to be problematic. What Isthmus did do, was determine a path of least impact, then devise a scheme for planting trees at a distance to block the most contentious lines of sight. In all, 17,000 trees were planted on some 440 properties—an approach said to be a world first.

Hobsonville Point in Auckland illustrates an entirely different design problem. How do you turn the site of an old disused seaplane base into a model 167-hectare suburb—one that will help mitigate the city’s housing shortage while meeting a range of social and environmental goals? Surprisingly, among the places Isthmus turned to for inspiration were the country’s Victorian and Edwardian suburbs. These suburbs were dense, with an average of 30–35 dwellings per hectare; they were “fine-grained”, with houses of differing size and type, varied streetscapes, and an admixture of commercial and sometimes industrial buildings; and they were “complete”, accommodating a wide cross section of society, and offering a range of amenities.

Hobsonville Point attempts to mimic all this, by paying attention to the things that build community, such as locating schools, shops, bus routes and cycleways in manner that reduces reliance on the car, constructing open spaces that offer children “safe” freedom, introducing narrow carriageways that encourage slow traffic, creating a mosaic of house types, and producing building and landscape designs that dissolve the boundary between public and private, house and street.

Hobsonville Point is a response to a housing shortage, but it is also the result of an enquiry into what makes successful suburbs appealing to live in. And here, as elsewhere, so much comes back to the land.

“Land needs to breathe, to be given space to exist,” says Isthmus co-founder David Irwin. “If we tread lightly and pay respect, we allow room for other things to happen.”