Kowhai

An often-straggly tree smothered with gold flowers each spring has long been a national favourite.

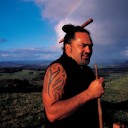

Some years ago I picked up two hitch-hikers and their dog, all cold and wet, battling their way north along the Desert Road. It was early spring, and as we passed beside Lake Taupo the kowhai there were in full flower. Inevitably, conversation turned to this spectacle, and once my passengers had learned I was a botanist, one of them, a young Maori woman, told me sadly that she had breached tapu, having accidentally cut down a kowhai tree whilst helping clear out her elderly nana’s overgrown orchard. Ever since then, she told me, things hadn’t gone right, and now she was heading back to the orchard to plant a scion raised from the tree she had felled. This, she hoped, would put things right. I sincerely hoped so too, for, superstitious or not, I couldn’t help but recollect that when my brother had deliberately cut down a kowhai tree while out in the bush, our grandfather had died and I had ended up in hospital with peritonitis.

Maori have long esteemed the kowhai for its colourful flowers, a welcome harbinger of spring, and its medicinal properties (see sidebar); also, I imagine, for the wealth of nectar-feeding birds it attracts during its flowering season, which they could harvest. One often sees venerable koran growing in the vicinity of old pa sites, kainga, urupa and other waahi tapu, and the trees are a feature of many a marae. Around Kawhia Harbour, I have been shown groves of kowhai held to be sacred. Indeed, as my passenger intimated, so prized are kowhai that many iwi do indeed consider the act of cutting one down—even accidentally—a serious breach of tapu.

My first memories of kowhai are from my time at primary school in Hamilton. My friends and I used to sit beneath several large kowhai trees at lunch-time. We loved them. Why? Because they changed with the seasons. In winter we saw that they were one of the few deciduous native trees, and we would watch them daily for the first signs of new growth, announced by the seemingly magical overnight production of flower buds. With their appearance we knew it would soon be spring, when we would be delighted by the trees’ rich profusion of golden flowers—portents of summer, the end of school and the start of the Christmas holidays. Later, after the flowers had fallen and the trees had sprouted leaves, we enjoyed their shade and gathered the long, curiously shaped seed pods with their tiny, hard, yellow, pea-like seeds, which we would use for play money, or, rather, “gold nuggets”, blissfully ignorant of their reputedly toxic properties (see sidebar).

On rare occasions a solitary tui would visit the stand, and the teachers would stop their lessons to admire the melodious, sometimes raucous, calls of a nectar-drunk native bird scarcely seen in the poorly forested farmland of the Hamilton basin. Many years later, when arsonists burned our old school to the ground, I was impressed by the trees’ remarkable resilience. Though seriously scorched, they recovered fully, and continued for some years to grace the footpaths leading to the replacement buildings.

My enthusiasm for kowhai is shared by my colleague Peter Heenan, who also has boyhood memories of the trees, in his case on the hills around Dunedin. Together we have studied the biology of kowhai and revised their taxonomy, recognising several additional species. Here we celebrate a tree considered by many an unofficial national symbol, and certainly one that has found a special place in the hearts of many New Zealanders.

[Chapter Break]

The scientific discovery of the kowhai began with Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander, the botanists who accompanied Captain James Cook on his 1768–71 Pacific voyage on HMS Endeavour. Cook made landfall in the eastern North Island in October 1769, when kowhai would have been in full flower, so it’s hardly surprising that Banks and Solander collected herbarium specimens and seeds to grow. One type was introduced to cultivation in Britain in about 1772, while another was grown in the Chelsea Physic (or Apothecaries’) Garden in about 1774.

Using the herbarium specimens, Solander prepared formal botanical descriptions of the two types for his Primitae Florae Novae Zelandiae, but following his untimely death this work was never published. It fell to others to complete what he had started. Using the names provided by Solander in his manuscript Philip Miller, for 48 years director of the Physic Garden, published a description of the plant there, Sophora tetraptera, and, in 1789, William Aiton, gardener at the Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew (and previously Miller’s assistant at Chelsea), did the same for the other, S. microphylla. However, since the naming of these two species, kowhai have had a problematic taxonomic history. In his Flora Novae-Zelandiae (published in 1853), Joseph Hooker—botanist, plant collector, explorer and friend of Charles Darwin—quotes Secretary to the Horticultural Society George Bentham as despairing “I cannot find any character to distinguish the New Zealand [Sophora] from each other, even as varieties: the leaves . . . show every gradation from the one to the other; so that I have in vain attempted to sort your specimens into varieties, without making one for almost every specimen.” Nearly 90 years later, Bentham’s frustrations were echoed by Dunedin botanists George Simpson and John S. Thomson, who in 1942 noted: “The genus is much in need of study to separate the many forms.” Despite which Simpson recognised a further species S. longicarinata, itself long known in horticultural circles by the illegitimate name “Sophora treadwellii”.

Head of the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research’s Botany Division at that time, Harry Allan, in a systematic treatise published in 1961 (as volume one of Flora of New Zealand), accepted S. tetraptera and S. microphylla as species but within S. microphylla he recognised two additional varieties, var. fulvida and var. longicarinata. In 1967, Russian botanist G.P. Yakovlev also accepted S. tetraptera as a species but, like Allan, recognised a number of varieties of S. microphylla. In 1981, Chinese botanists Tsoong Pu-chiu and Ma Chi-yun published a worldwide revision of the genus Sophora and accepted four New Zealand species: S. prostrata, S. microphylla, S. tetraptera and S. chathamica.

Following our own research, Peter and I recognise eight species of New Zealand Sophora, having distinguished a number of new species within the previously rather variable S. microphylla. The New Zealand species are now S. chathamica, S. fulvida, S. godleyi, S. longicarinata, S. prostrata, S. microphylla, S. molloyi and S. tetraptera. Each of these has its own story to tell.

[Chapter Break]

We now know that all the New Zealand species of Sophora are endemic—that is, they are peculiar to New Zealand. S. microphylla (small-leaved kowhai) has traditionally been considered to occur also in Chile and on Gough Island, in the south Atlantic Ocean, but we believe the Chilean pélu (to use its common name) is a separate species and should be known as S. cassioides. Gough Island plants also belong to this species.

S. microphylla is the most widespread of the New Zealand species, being found throughout both the North and South Island. It grows most commonly on alluvial river terraces, dunes and flood plains, along lake margins, and on hillsides among loose rock and rubble, often associated with divaricating plants and mixed podocarp/hardwood forest. It differs from all the other New Zealand species in having a distinct divaricate sapling phase and conspicuous yellow/orange-brown juvenile stems. The juvenile phase is of variable duration: in the lower South Island, it may last for more than 20 years.

There is considerable variation, too, in the growth habit of S. microphylla. Some plants are upright and spreading, while forms near Maruia (north Canterbury) and Taihape (Rangitikei district) have a distinctly weeping adult growth habit, and others along the Rakaia River (central Canterbury) often have multiple trunks arising from near ground level.

S. chathamica (coastal kowhai) grows in coastal and lowland areas in the northern North Island, around Wellington (on Kapiti, Mana, and Matiu/Somes Is, and at Paremata and Papakowhai) and, as its name suggests, on the Chatham Islands. It has crowded and overlapping leaflets, those near the stem being larger than those near the leaf tip. The leaflets are longer and wider than those of the other New Zealand species except S. tetraptera. It is a generalist in its habitat requirements, flourishing on limestone, volcanic outcrops, alluvium and stream banks, beside mangrove swamps, and on hillsides. It is frequently associated with mixed podocarp/hardwood forest and coastal scrub.

The distribution of this species is especially interesting. The southern limit of the northern North Island population is near latitude 39° S, a common biogeographic boundary. Apart from its presence in the Wellington area, the species is absent from the lower North Island, consistent with another well-known biogeographic feature, the lower North Island floristic gap. It is possible that the Wellington occurrences are not natural but the result of deliberate plantings, for their distribution corresponds with the location of historic Maori settlements and pa sites. Given the importance of kowhai to Maori, it is quite likely that S. chathamica was deliberately introduced to the area by western Waikato Maori (Ngati Toa) who participated in the southerly migration initiated by Te Rauparaha. It is likely, too, that the species’ occurrence on the Chatham Islands is the result of the movement of Taranaki Maori (Ngati Mutunga and Ngati Tama) who accompanied Te Rauparaha to Wellington before migrating to the islands.

While we don’t know any of this for certain, we do know that other important plants, such as New Zealand flax (Phormium tenax), were transported by these same migrating Maori, and there is an oral tradition that tells of western Waikato Maori taking kowhai with them when they moved south. During 2001 we discovered an isolated specimen of S. chathamica at the head of the remote Whanganui Inlet, in north-west Nelson—another location where western Waikato Maori settled—providing further evidence that plants were deliberately moved.

Two of the new species of New Zealand kowhai are very similar in having densely hairy leaves with numerous, crowded leaflets that are more-or-less sessile (without stalks). S. fulvida (Waitakere kowhai), previously known as S. microphylla var. fulvida, is found in the northern half of the North Island, and is most common in the Waitakere Ranges, west of Auckland, where it grows on base-rich volcanic basalts and andesite and breccia outcrops that protrude from the dense mixed podocarp/hardwood forest. Its leaflets are elliptic to elliptic-oblong in shape.

S. godleyi (Godley’s kowhai, or papa kowhai; Eric Godley is famous for his collection of kowhai seeds, see sidebar) is restricted to the central North Island, where it is particularly abundant in the catchments of major south-draining rivers, such as the Pohangina, Rangitikei, Turakina, Whanganui and Mangawhero. It usually grows on calcareous limestone, mudstone, siltstone or sandstone, as well as on alluvium derived from these substrates. Its distribution may have been influenced by the Taupo volcanic eruption some 1850 years ago, for it doesn’t extend north onto the ignimbrite of the central plateau. The leaflets of S. godleyi are ovate to more or less orbicular, and the hairs are usually curly, curved or twisted.

Another species with numerous small leaflets is S. longicarinata but in this case they are distant from each other, lack hairs and have distinct stalks. However, like S. fulvida and S. godleyi, S. longicarinata favours base-rich substrates, growing as it does on limestone and marble bluffs and outcrops in northern Nelson and western Marlborough. It is unusual in that it can form a densely branched shrub or an upright small tree with several trunks and main branches. It often has branches arising from below ground level, and a single shrub up to 1.5 m high can have an extensive network of underground branches and rhizomatous shoots.

As well as small, numerous leaflets and a preference for base-rich substrates, S. fulvida, S. godleyi and S. longicarinata share a number of other features. They grow mainly on unstable bluffs, rock outcrops and hillsides, habitats not usually subject to temperature inversions or excessive frost but which are constantly being weathered and eroded and are therefore often free of dense vegetation despite having highly fertile soil. Notably, they do not undergo a juvenile divaricating phase, which allows for quick growth and a first flowering just a few years after establishment. It is unknown at present whether the similarities of these three species are a result of convergence due to their evolving under similar ecological conditions or of their sharing a common ancestor.

A species with a particularly restricted distribution is the newly described S. molloyi (Cook Strait kowhai; Brian Molloy is a conservationist, taxonomist and plant ecologist). This is found only on islands in Cook Strait, such as Stephens Island, Kapiti Island and the Chetwode Islands, and on several headlands along the south Wellington coast. It has specific habitat requirements, favouring sunny, north-facing cliffs and scree, also active alluvial fans, usually in extremely exposed locations where drought, salt burn and wind damage can be severe. On some exposed rocky sites it is the dominant or, indeed, only shrub species.

S. molloyi has a prostrate or bushy growth habit. It is usually broader than it is high, branches above ground level, lacks suckers or rhizomes, and often has decumbent and prostrate main branches and trailing stems several metres long. A 40-year-old cultivated specimen at the Landcare Research herbarium at Lincoln is 6 m tall and 12 m across. Flowers are usually dispersed through the leafy canopy, from autumn to late spring.

The two remaining species, S. prostrata (prostrate kowhai) and S. tetraptera (large-leafed kowhai), are well-known but differ greatly in appearance and distribution. S. prostrata is particularly distinctive because of its divaricating habit, which is retained throughout it’s life. This is a species confined to the eastern South Island where it grows on dry and exposed hillsides and rock outcrops with other divaricating plants, such as coprosmas and matagouri (Discaria toumatou). It is a small shrub, usually 1–2 m tall, with highly interlaced branchlets, and can have a suckering growth habit. Its flowers are especially distinctive, being small, inverted, and with an orange standard petal.

In contrast, S. tetraptera occurs in the central and eastern North Island and is commonly associated with lowland temperate/maritime forest, growing amongst five-finger (Pseudopanax arboreus), kohuhu (Pittosporum tenuifolium) and broadleaf (Griselinia littoralis). It also grows on open, eroding or disturbed sites on the central North Island ignimbrites and eastern North Island sandstones and mudstones. Its leaves are easily recognised on account of their large size and numerous leaflets.

[Chapter Break]

The eight New Zealand species of kowhai belong to Sophora sect. (i.e. section) Edwardsia, a sub-genus grouping that includes eight further species scattered over islands throughout the southern Pacific Ocean, a single species in the Indian Ocean and two species in Chile. Transoceanic dispersal of seed is clearly an important factor in the biogeographic and evolutionary history of the group. Seeds of S. chathamica and S. microphylla are known to float from the New Zealand mainland to some outlying islands, having been collected from beaches on the Kermadec and Chatham Islands respectively, although they have not been found to have germinated and taken root there.

Recent studies of DNA sequence data have revealed that the majority of species of sect. Edwardsia have highly similar sequences, indicating a very recent and rapid radiation around the southern Pacific Ocean. Molecular clock estimates used to determine the age of sect. Edwardsia suggest that most of the species have evolved during the last 0.5–2.0 million years (myr). This timeframe is consistent with the ages of the volcanic islands on which many of the species occur. For example, Lord Howe Island (S. howinsula) is about 6 myr old, Rapa Nui/Easter Island (S. toromiro) is between 5.1 and 5.2 myr old, and Masafuera Island (S. masafuerana) is between 1.0 and 2.4 myr old. None of the volcanic islands in the southern Pacific Ocean have more than one species of Sophora sect. Edwardsia, a situation consistent with a single founder event. New Zealand, with eight species, is a distinct contrast, and it is most likely that this archipelago is a centre of radiation.

DNA research has also shown that the pantropical S. tomentosa, incidentally the type species of the genus, is the closest living relative to Sect. Edwardsia, the section to which the New Zealand species belong. S. tomentosa and most of the species from sect. Edwardsia share hypogeal germination (whereby the cotyledons appear below the ground), leaves without stipules, and round filaments. These species also have buoyant seeds, and are distributed by ocean currents throughout the pantropics (S. tomentosa) and around southern temperate oceanic islands (sect. Edwardsia). S. tomentosa differs from the species of sect. Edwardsia by its short-lived, vine like, stems, which periodically die back to the ground where they are then replaced by another emergent stem and the structure of its flowers and seed pods.

[Chapter Break]

Visit any New Zealand school today and you will almost certainly find kowhai trees growing within the grounds. They are also popular in urban parks, reserves and gardens, being readily available at nurseries and garden centres. However, many cultivated plants are hybrids, displaying a variable assemblage of leaf forms, growth habits and flowering times. Sophora microphylla, S. chathamica, S. fulvida and S. tetraptera are the most likely parents, variously combined. The Lord Howe Island kowhai (S. howinsula) and the Chilean pélu (S. cassioides) are also grown in New Zealand, usually identified incorrectly as one of these four New Zealand species.

S. howinsula has an obscure history in New Zealand, and is often sold under the cultivar name Otari Gnome. It forms a compact shrub, has particularly large flowers and is a good garden plant. In the 1980s, the Levin Horticultural Research Centre gave a selection of S. cassioides the cultivar name Goldilocks. Because S. cassioides can hybridise freely with the New Zealand species, and because it has some similarity to S. chathamica and could therefore be used in the restoration of native forest habitats, there are strong grounds for recommending it be withdrawn from cultivation and that superior selections of New Zealand species be introduced to horticulture so as to retain the unique characteristics of this iconic native tree. Given the range of variation among kowhai, horticultural selections could be made for differences in growth form, the size, shape and colour of leaves, flowering habit and deciduousness.

[Chapter Break]

With the recognition of eight, rather than three, species of New Zealand kowhai comes a need to review the tree’s conservation status and current conservation practices. Three species—S. fulvida, S. longicarinata and S. molloyi—are now listed by the New Zealand Threatened Plant Panel. S. fulvida as “Chronically Threatened/Gradual Decline”, while both S. longicarinata and S. molloyi are “At Risk/Range Restricted”. These assessments indicate that all three species—especially S. fulvida—require some level of conservation monitoring to ensure they are not in decline.

Officially, populations of S. fulvida on Maunganui Bluff (north of Dargaville), Mt Manaia and Bream Head (Whangarei Harbour), as well as those in the Waitakere Ranges, are presumed to be stable. Nevertheless, some of the Waitakere populations are clearly declining as a result of weed invasion, and there is evidence of deterioration at Bream Head and Maunganui Bluff. Meanwhile, a solitary occurrence on Mt Karioi (near Raglan) calls for a proper survey of the area.

S. molloyi and S. longicarinata owe their index status to the fact that they occupy extremely restricted ranges. Of the two, S. molloyi is perhaps at greater risk, for most of its mainland occurrences are on private land subject to stock browsing. The species has recently suffered significant losses at Cape Palliser, in the Wairarapa. If this trend continues, S. molloyi might soon qualify for a more serious listing.

The other species seem relatively secure, though S. microphylla is now scarce in parts of its northern range, and many occurrences are small groves or lone trees growing in isolation in otherwise bare paddocks, thus with little long-term hope of regeneration. There is a strong argument to be made for a Project Golden along the lines of Project Crimson, which advances the cause of rata and pohutukawa. Objectives could include the protection of riverside and paddock stands and ensuring that cultivated stock available from nurseries is hybrid-free and correctly labelled.