Heads in the clouds

How can the sensitive tissues of a plant withstand the brutal conditions of the mountains? Unlikely as it may seem, many fascinating plants, including the distinctive penwiper, Notothlaspi rosulatum, not only survive but flourish amid the shifting screes and windswept gullies far above the treeline. Alpine plants are among the special treasures the mountains offer those who venture among them.

From the crest of the West Coast’s Lange Range, between breaks in the cloud, I can see Ivory Glacier calving miniature icebergs into its green meltwater lake. The descent to the lake takes me across shattered scree slopes—the residue of mountains ravaged by the rigours of an alpine climate. As loose rocks are sent tumbling by my footfalls, I spot something bright in the otherwise dreary grey.There, nestled among the scree, is a delicate yellow bloom—the flower of one of our endemic alpine buttercups, Ranunculus godleyanus, found only in the central part of the Southern Alps between Aoraki/Mt Cook and Arthur’s Pass national parks. This little plant exists in one of the more hostile environments on earth, and yet it looks as if it would be withered by the merest hint of frost.

Although I am making this trip in summer, when daytime temperatures reach well into the 20s, snow fell on the peaks two nights ago during a southerly blast. I am thankful the winds are calm today—not the 150 km/hr gusts which can whip you off your feet. Living in the mountains is tough. I’m merely a visitor, protected in my windproof coat, woolly hat and leather boots. For alpine plants, the mountains are a year-round home, and it is often a harsh, unforgiving one.

As I approach the glacier, melting water cascades everywhere, dancing down clefts and ravines, seeping from the ice and snow above. While water is abundant now, during winter, freezing temperatures will mean much of it is in the form of ice, unavailable to plants.

Parched in summer, frozen in winter, buffeted by wind, bruised by rockfall—these are some of the problems faced by plants living in the mountains. Despite these hardships, alpine plants thrive in this demanding environment. In fact, almost half of New Zealand’s native plants live in the mountains, testimony to their remarkable tenacity.

Near the lake edge, I reach a moss-carpeted shelf where a small stream tumbles from bluffs above. In the sheltered enclaves of the cliffs, an astonishing range of alpine plants are growing. Through the vibrant greens of the mosses sprout edelweiss, marguerites, gentians and bristly carrots. Beyond, the snout of the glacier ends abruptly at the lake edge. I marvel at the contrast—a delicate flowerbed in a world of almost Antarctic barrenness.

South Island edelweiss, Leucogenes grandiceps, is not closely related to its Swiss namesake, but survives equally well in our antipodean mountain world. Along with many other alpine plants, edelweiss is a herb—a vascular plant without a woody stem. Small leaves, packed tightly in a circle, form what is called a rosette. This form is common among alpine herbs, with the leaves arranged to maximise the surface area exposed to sunlight. In the short growing season, alpine plants must adopt forms which make the most of the sun’s energy.

There is a danger, however, in exposing too much leaf surface. Large surfaces mean more area for precious water to escape, drawn by the wind’s incessant pull. Alpine plants avoid water loss in several ingenious ways. Most of the Celmisia daisies, for example, have woolly leaves, which are actually covered with fine hairs. The hairs help insulate the leaves and reduce the air flow next to the leaf surface.

Earlier, while crossing Whitcombe Pass, I had drunk from the cup-shaped leaves of a Mount Cook lily. As broad as dinner plates, the leaves capture precious droplets of dew, rain and mist. Actually not a lily at all, Ranunculus lyallii is the world’s largest buttercup, and is a signature plant of the Southern Alps.

Below Ivory Lake Hut, after weaving through some bluffs, I reach the tussock fields of the Waitaha, a remote West Coast valley. Snow tussocks (Chionochloa spp.) are a type of native grass, often filling the valley floors or lower mountain flanks in carpets of waving gold.

Some of these grasses, such as red tussock (Chionochloa ruln–a), can live for more than 100 years and reach two metres in height. They are masters of mountain habitats. In winter, when frozen soil causes a drought, the plants become dormant. Their leaves curl inwards into long, tight spirals, looking like thin stems, and are adept at withstanding both the wind and the crushing weight of winter snow. Water channels along the leaves into the plant’s centre, to give extra moisture during wet, damp days. Dead leaves curl up, to eventually become part of the soil at the base—an important means of recycling minerals and nutrients in an environment where nothing can be wasted.

Plants which take this self-composting strategy to an extreme are the “vegetable sheep” of the genus Raoulia and Haastia. They are covered in a thick, woolly layer of leaves, packed so tightly together that the branches are hidden. Underneath the plant a sort of peat forms from the decay of any dead branches and leaves. The nutrients and moisture are trapped inside, and the vegetable sheep lives partly on the product of its own decay. Because of their woolly appearance, vegetable sheep have fooled many a high-country musterer into sending their dogs over yonder ridge, chasing the lost “sheep” back to the flock. Some of the larger ones, such as Raotilia eximia, can reach a span of more than two metres.

The low, ground-hugging form of vegetable sheep is one adopted by many alpine plants to escape the wind. Other plants choose sheltered crevices and cracks, but these spots have disadvantages. Crevices fill with snow, and may be shaded when more open places enjoy sunshine.

While on a calm summer’s day an adaptation such as a creeping, prostrate form may seem immaterial, when the wind is at its full fury that growth habit may mean the difference between survival and being uprooted. The mountains can be a frightening place in a high wind. Once, in a howling gale on the Ruahine Range, I was forced to crawl the last 300 metres to a hut. Earlier a gust had picked me up, pack and all, and hurled me three metres into a snow tussock. Keeping down among the tussocks, I was able to crawl to safety.

Some plants ignore the lie low rule and use a different strategy: be supple. The whipcord growth form of some Hebe is ideally suited to bending with the wind. Here the secret of success is not to resist but to go with the flow. Lycopodium, some of which are brilliant gold colours, adopt both strategies. Their flattened leaves are more wind resistant, and they can survive the worst storms.

Some plants ignore the lie low rule and use a different strategy: be supple. The whipcord growth form of some Hebe is ideally suited to bending with the wind. Here the secret of success is not to resist but to go with the flow. Lycopodium, some of which are brilliant gold colours, adopt both strategies. Their flattened leaves are more wind resistant, and they can survive the worst storms.

Many alpine plants take advantage of the shelter provided by their neighbours. Alpine gardens growing in multispecies whorls around rocks and crevices are common above the bushline. In the miniature valley between the hills of two adjacent vegetable sheep, a tiny bluebell may find protection from the elements. Tussocks also harbour many species between them.

While weaving your way through waist-high tussocks, their flexible foliage brushing above your gaiters, you shouldn’t get complacent. Tussocks can hide some nasty plants, such as Spaniard, or speargrass.

So called because of their stiff, rapier-sharp leaves that bristle in every direction, Spaniards are not shy about stabbing the unwary tramper, and make a painful seat if you choose to flop down in the wrong spot. Although their spiky appearance would suggest otherwise, Aciphylla belong to the carrot family, along with other alpine plants including the smaller—and softer—A nisotome, or bristly carrots.

One speargrass specimen, Aciphylla colensoi, is named after the missionary William Colenso, who made many botanical discoveries in his explorations of the North Island. Unwelcome attention from Spaniards prompted Colenso, during one of his trips in 1845, to write, “It gave us an immense deal of unpleasantness, trouble and pain—often wounding us to the point of drawing blood.”

The “rugged individualists” of the mountain flora spurn the protection of an alpine community, with its shelter, more stable soils and higher humidity, and live in the most barren of habitats. Sixteen alpine plant species have adapted to life on scree slopes—the epitome of instability. These plants often have roots which probe deep into the damp soils under the mantle of loose rocks. Trailing rhizomes and prop roots enable them to resist movement of the scree, and they quickly put up new leaves if the old ones get buried. Further, many scree plants die down during winter, when scree movement is greatest, thereby avoiding the period of maximum disturbance.

Many alpine plants take advantage of the shelter provided by their neighbours. Alpine gardens growing in multispecies whorls around rocks and crevices are common above the bushline. In the miniature valley between the hills of two adjacent vegetable sheep, a tiny bluebell may find protection from the elements. Tussocks also harbour many species between them.

While weaving your way through waist-high tussocks, their flexible foliage brushing above your gaiters, you shouldn’t get complacent. Tussocks can hide some nasty plants, such as Spaniard, or speargrass.

So called because of their stiff, rapier-sharp leaves that bristle in every direction, Spaniards are not shy about stabbing the unwary tramper, and make a painful seat if you choose to flop down in the wrong spot. Although their spiky appearance would suggest otherwise, Aciphylla belong to the carrot family, along with other alpine plants including the smaller—and softer—A nisotome, or bristly carrots.

One speargrass specimen, Aciphylla colensoi, is named after the missionary William Colenso, who made many botanical discoveries in his explorations of the North Island. Unwelcome attention from Spaniards prompted Colenso, during one of his trips in 1845, to write, “It gave us an immense deal of unpleasantness, trouble and pain—often wounding us to the point of drawing blood.”

The “rugged individualists” of the mountain flora spurn the protection of an alpine community, with its shelter, more stable soils and higher humidity, and live in the most barren of habitats. Sixteen alpine plant species have adapted to life on scree slopes—the epitome of instability. These plants often have roots which probe deep into the damp soils under the mantle of loose rocks. Trailing rhizomes and prop roots enable them to resist movement of the scree, and they quickly put up new leaves if the old ones get buried. Further, many scree plants die down during winter, when scree movement is greatest, thereby avoiding the period of maximum disturbance.

Scree plants help stabilise slopes through their network of roots and ability to build soils. One scree specialist found in eastern parts of the Southern Alps from Marlborough to Canterbury, the attractive penwiper (Notothlaspi rosulatum), grows in a rosette of grey leaves which blend perfectly with their surroundings. During December to February they produce a small but spectacular dome of flowers.

Over a period of decades, scree slopes may eventually become stable enough for other plants to make new homes. As the scree stabilises, the community of plants on the slope slowly changes, too. Sometimes the pioneer plants are ousted by a succession of more aggressive newcomers which arrive once the soils are more established. However, there will always be new scree slopes to colonise, and avalanches continually open up fresh rocky surfaces. In the volcanoes of the North Island, lahars and lava flows create new habitats for colonising plants. Some slopes are too unstable to ever be colonised fully.

[Chapter Break]

To be considered a true alpine plant, a species must grow in a zone which lies between the bushline—the attitudinal limit beyond which no trees can grow—and the snowline. In this zone, herbfields, fellfields, scree and tussock grasslands are the major habitat types.

The altitude of the bushline depends on summer temperatures, which vary with latitude, but proximity to the sea also plays a factor. In the central North Island the bushline may be as high as 1450 m, while in the deep south trees may not grow at altitudes above 900 m. The snowline varies between about 2000 and 2400 m.

Often the edge of the bush is not a sharply defined line, but more of a transitional zone where cold-resistant shrubs can survive. One of the commonest subalpine shrubs is the dense, scratchy leatherwood, almost impenetrable to trampers. Leatherwood forms a distinctive subalpine scrub band in many mountains, reaching its greatest extent in the Ruahine and Tararua Ranges, central Westland and Stewart Island. Above the subalpine zone, only true alpine species can survive.

Three major vegetation zones are recognised in mountains, and within these zones different plant communities exist.

The low alpine zone is the area immediately above the bushline. In this area lie the herb and tussock fields where most alpine plants live, including buttercups, daisies, speargrass, snow tussocks, Astelia, foxgloves, gentians, eyebrights, orchids and Anisotome. Five hundred metres above the bushline, the tussock and herb fields fade out.

In the high alpine zone, plants are smaller, fewer and scattered among expanses of rock. Plants of these areas, called fellfields, include gentians, some buttercups, daisies and Hebe. Here also are the vegetable sheep, Raoulia and Haastia, surviving as low cushions over rocks. A few sedges and grasses exist in fellfields as well. Scree slopes occur where shattered rock, shed from outcrops and bluffs, spills down steep gullies and slopes.

The nival zone begins about 900 m above the bushline, where permanent snow persists for most of the year. Only the hardiest plants can survive here, including mainly vegetable sheep, lichens and mosses. Only three flowering plants reach the nival zone: Hebe haastii, Ranunculus grahamii and Parahebe birleyi.

Like their lowland counterparts, alpine plants rely primarily on wind and animals to disperse their seeds. With such a short season for growth and reproduction, many mountain plants prepare flower buds the previous year. After the returning warmth of spring melts the snows, plants can be flowering within a few days, ready to attract insect pollinators.

New Zealand’s native flowers, although diverse, are not well known for the spectacular colours and complex shapes seen in many other parts of the world. Many produce simple flowers in plain white or yellow. A few exceptions exist, such as bluebells, but even these blooms fade quickly to paler tones. New Zealand was isolated from the rest of the world when specialised pollinators such as long-tongued bees and butterflies evolved. Our more primitive native insects have primitive short tongues, and lack colour-sensitive vision.

To attract the attention of moths, flies and beetles—the main pollinators—some native alpine flowers, as the prolific Celmisia daisies, wave their flowers on long stalks. These “flowers on stilts” are effective, and it is not unusual to see a daisy with an insect on every flower head.

Wind, so often the enemy which desiccates alpine plants, becomes a friend to help distribute pollen and, later, seed. Tussocks use wind to great effect and produce vast quantities of airborne seeds. Daisies are famous for their numerous seeds, too, which can lift into the air on the faintest of breezes.

Some alpine plants opt for a “quality rather than quantity” approach to seed dispersal. Making just a few juicy berries, these plants entice animals to spread their seeds. Snowberries (Gaultheria spp) are the most familiar alpine berries, coming in a succulent red, pink or white.

Snow totara, Podocarpus nivalis, also produces red berries, feeding kea and wood pigeons venturing above the bushline. Once eaten, the seed can be transported for miles, courtesy of its winged host. When finally defecated, the seed sits in the bird’s nutritious waste, ready—with luck—for germination.

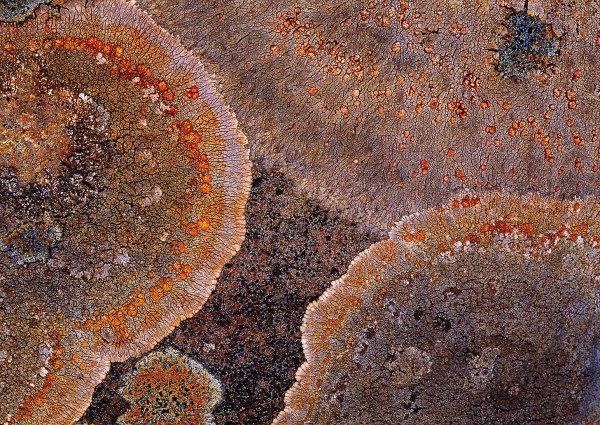

Only a very few plants are hardy enough to colonise the most extreme alpine environments. Incredibly, lichens are known to grow on the summit rocks of Aoraki/Mount Cook, making them the highest form of life in New Zealand. Able to withstand extremes of desiccation, lichens secrete an acid which can dissolve rock surfaces to form primitive soils. True pioneers, they require only rocks, water and air to survive. In such cold extremes, lichens are slow growing, and some may be hundreds or even thousands of years old.

Another harsh environment for mountain plants are alpine bogs, like those adorning the tops of the Douglas Range, in Kahurangi National Park. Alpine soils are notoriously poor at holding nutrients, and nowhere is this truer than alpine bogs. Closer examination of these bogs sometimes reveals dense patches of tiny plants with club-like leaves. These are sundews (Drosera), of which New Zealand has several species. One often sees the carcasses of small insects caught in their leaves—a grim clue as to how these plants get their nitrogen and phosphorus. Sundew leaves have numerous hairs, each secreting droplets of sticky glue. Foraging insects become caught among the hairs, and are slowly digested by the sundew’s enzymes.

The innocent-looking eyebrights (Euphrasia) have also solved the nutrient problem, not by murder, but by theft. Tapping into their neighbours’ roots, these floral vampires steal liquid nourishment.

While plants such as tussocks may have to contend with thieving eyebrights, for many alpine plants a more serious threat comes from browsing animals, especially insects. New Zealand has only 15 species of grasshopper, but 12 of them are found in the mountains. They come in a range of colours, depending on their habitat. Those at the bushline are camouflaged by their green, gold or brown colour, while those higher up are almost indistinguishable from the grey scree. In summer, alpine herbfields are often alive with their leaping antics. On several occasions I have seen pairs mating, the smaller male perched on the female’s back. If you take a step too close she leaps away, carrying the two of them to safety. A host of other insects inhabit the alpine gardens, including native bees, giant weta, butterflies, moths, flies, caterpillars, giant weevils and beetles.

With all these hungry insects munching away, it is not surprising that alpine plants have developed some defence tactics. While some—such as the penwiper—choose camouflage, adopting the subtle colours of their surroundings, others rely on their leaf hairs to discourage predators. A hairy surface is difficult for a leaf-eating insect to get hold of, making the meal a tiring experience. The tough hairs themselves are hard on the insects’ mandibles, which mean fewer leaves get eaten.

While mechanical defences are good, chemical defences are better. Many alpine plants are filled with toxic and irritating chemicals. Tiny crystals beneath the surface of the leaf can give insects an unpleasant taste in their mouths. Leaves, hairs, stems, and flowers can all be laced with insect-deterring compounds. Southern heaths, a family which includes the common Dracophyllum genus, make good use of these foul-tasting chemicals in their leaves.

[Chapter Break]

One of the enigmas of New Zealand’s alpine plants is their evolutionary history. Around 93 per cent of our alpine plants are endemic, evolving into unique forms in our mountains. Yet our mountains are only five million years old—a mere blink of the eye in evolutionary time. For the previous 50 million years New Zealand was a low-lying flat expanse, with a much warmer, subtropical climate than the one we have today. How could so many alpine plants (more than 600) have evolved in such a short time?

Alan Mark, professor of botany at Otago University, has wrestled with this question for over 40 years. One theory suggests that some of New Zealand’s alpine plants may have evolved from related lowland species. Habitats such as infertile bogs, cliffs, and shady ravines may have harboured plants which liked cooler conditions during the warm periods in New Zealand’s history. After the mountains were built, new alpine habitats were created, and the cool-loving plants could then move into the mountains.

If our alpine plants did evolve in this way, then one would expect to find closely related species still down in the lowlands. While this is the case for some alpine plants, it is not true for all. Mark cites the instance of Hectorella caespitosa, a species with no close relatives anywhere, and one which seems to have evolved inexplicably quickly.

Mark puts more credence on a second theory, which postulates that most of New Zealand’s alpine flora reached here from other countries as seeds and spores carried by winds and birds. Southeast Asia, Tasmania and pre-glacial Antarctica are the most likely sources.

The recent discovery of fossilised beech leaf remains in Antarctica, dated as young as 5 million years backs up the idea that Antarctica could have been a seed source for some of our alpine plants. “Unfortunately, herbaceous plants don’t preserve well,” says Mark, “and we don’t have firm evidence yet.”

[sidebar-1]

The ancestors of plants such as Hectorella may have lived in Antarctica, and reached our shores by wind or bird dispersal. When the ice sheets advanced over Antarctica, only the New Zealand descendants would have remained.

But precisely how and when they got here, says Mark, remains a mystery.

[Chapter Break]

Despite their impressive ability to adapt and survive in the mountains, many alpine plants are threatened by the changes humans have brought. Fire, combined with grazing, has probably been the most significant problem, particularly in the drier mountains of Otago, Canterbury, Nelson and Marlborough.

Maori burned areas in their hunt for moa, and European settlers torched tussocklands in order to provide grazing for sheep. Burning became a frequent, often romanticised, part of high-country life, used to stimulate new growth in the tussocks.

Repeated burning, heavy grazing and the introduction of rabbits had a devastating effect on many native plants. Erosion became widespread, and introduced weeds such as hawkweed (Hieracium spp.) thrived. Only in recent years has formal protection come to some of these drier eastern mountains. Part of some pastoral leases, considered unsuitable for further grazing, have been set aside as reserves administered by the Department of Conservation. There is still much progress to be made in these neglected eastern mountains, and weeds continue to provide a threat to the native plant communities which live there.

Along with sheep and rabbits, European colonists brought several other mammals which ran wild and started to affect native alpine ecosystems. Tahr, deer, chamois and hares were among the imports. The mechanical and chemical defences of native plants, effective against local insects, were virtually useless against the new invaders. Browsing by introduced animals saw the retreat of the most vulnerable alpine plants to the relative safety of inaccessible ledges, crevices and ravines.

Tahr are natives of the Himalayas, and, after being introduced to Mt Cook in 1904, have spread to occupy the central areas of the Southern Alps, between the Landsborough and Whitcombe Rivers (see New Zealand Geographic, Issue 23). Extremely agile, tahr are able to reach the most inaccessible of alpine plants to forage. Instead of selectively grazing, they typically feed in herds, and may wipe out whole areas of the most succulent alpine plants.

Chamois were imported from Europe, and, like tahr, liberated in the Mount Cook area. Now widespread throughout the Southern Alps from Nelson Lakes to Mt Aspiring, and spreading in Fiordland, they roam widely over the alpine zone down to the bushline. Their diet includes snow tussocks, herbs and Dracophyllum species.

Hares, also imported from Europe, have become naturalised to mountain environments. While the sword-like leaves of spaniards may have deterred moa browsing, they seem to be no impediment to alpine hares, and it is not uncommon to see these plants heavily browsed.

Up until the late 1960s, introduced wild animals caused widespread damage to alpine ecosystems. Through the advent of helicopters and live-recovery techniques developed in the 1970s and ’80s, thousands of these ungulates—mostly red deer, but also tahr and chamois—were shot or caught in nets to be taken out to farms. The mountain gardens had a temporary reprieve. Many places, devastated by decades of browsing, recovered into dense mosaics of lush alpine growth.

Among the plants most at risk from browsing are some highly palatable, rarer alpine species such as Ranunculus godleyanus, the buttercup I saw near Ivory Lake. This species has been found in as few as 20 sites in the central Southern Alps, although its inaccessible habitats and conspicuousness only during the summer probably mean it is more widespread than has been recorded.

While browsers seem to be under at least a level of control, introduced weeds are spreading at a rate that is causing concern. Landcare Research scientist Claire Newell recently remeasured alpine plant plots in the Avoca-Harper catchments of Canterbury’s Craigieburn Forest Park which had been monitored regularly between 1955 and 1980. She found that the diversity of alpine plants in the plots had increased significantly by 2000—a result she attributes to recovery after several periods of intensive browsing by deer and chamois between the late 1940s and early 1980s.

However, she also found that two species of introduced Hieracium, which first appeared in the 1965 data, were present in much larger numbers. In 1980, Hieracium lepidulum occupied only 17 per cent of plots. By 2000, that had doubled to 38 per cent. In comparison, H. pilosella, the hawkweed common to lower-altitude grasslands such as the Mackenzie basin, occupied only 5 per cent of plots in 1980, but by 2000 was present in nearly 30 per cent.

H. lepidulum invades the litter layer beneath tussocks, and may restrict tussock seedlings from establishing, whereas H. pilosella appears to outcompete alpine herbs growing between the tussocks.

In parts of the central North Island and eastern South Island, ling heather (Calluna vulgaris) is a serious threat to alpine plant communities. Used to harsh northern hemisphere winters, heather is much more aggressive than many native plants, and its distinctive purple hue has spread quickly—especially in Tongariro National Park.

Introduced in 1912, by 1921 heather covered 1200 ha of our oldest national park. By 1993, it covered over 600,000 ha. Harry Keys, advisory scientist for the Department of Conservation in Turangi, says heather is a major problem because it can grow to about a metre high, and although some native plants can penetrate its canopy, many are smothered.

Pulling the weed out or using sprays has proved only partly effective, and large-scale control would be very expensive. More hope lies with biocontrol. Since 1995, a beetle, Lochmaea suturalis, which feeds only on heather, has been introduced, and appears to be having an effect.

An even more ominous threat comes from a North American import. Lodgepole pine, Pinus contorta, is a relative of the familiar radiata pine. The government conducted test plantings of contorta on the southern slopes of Ruapehu in the 1920s and 1930s. It soon became apparent that not only was lodgepole pine almost useless for wood, it was an aggressive weed.

Capable of growing at higher altitudes than native trees, it threatens to take over parts of the alpine zone. In Tongariro National Park, it has taken 25 years of back-breaking work by conservation staff, the army and volunteers to bring the weed under control.

Other areas, such as the eastern South Island and Kaweka Forest Park, are not faring so well. In the south-eastern Kaweka Ranges contorta has marched across the southern ridges, shading out many native species, and in places is so thick that pushing through it has become virtually impossible. Each year, the Department of Conservation tackles areas of contorta for removal, but it is an ongoing and expensive battle.

In the eastern South Island, there is no control, and contorta threatens to change tussocklands into exotic forests.

Despite the clever bag of tricks which alpine plants have developed to survive, new threats in the mountains pose a clear challenge to their existence. Recent increases in biodiversity funding should enable the Department of Conservation to better protect the unique flora of our mountains. With continued vigilance against fire, weeds and browsing mammals, alpine plants might recover—at least in places—to their full pre-human glory. These hardy plants, some of which live where only climbers dare to tread, surely deserve this chance.