The rocks of Castle Hill

Nestled among the eastern ranges of the Southern Alps, an hour’s drive from Christchurch, lies a gentle basin bulging with huge boulders and rock outcrops. The area, known as Castle Hill or Kura Tawhiti, is a Mecca for rockclimbers and skiers, but long before Europeans and their sheep appeared, Maori appreciated that the place had a special magic—one that not even the snows of winter could shroud.

Admit it: I’ve never liked the Canterbury Plains. For me, there’s something irreverent about the plethora of straight lines inherent in intensive agriculture. Brian Turner’s poem Crossing the Canterbury Plains sums up the problem of a place “where a leaf may be blown for a hundred miles, and end up somewhere much the same.”

The land here is so altered from its natural state it barely has any vestiges of its former self. Only the Plains’ creators, the untameable rivers that tumble from Alps to sea, hint at a wilder landscape in the interior. Among them is the Waimakariri, which flows like an artery from the savage heart of the land. As I drive westward, parallel to the mighty river, I feel a rising elation as the purple hills grow inexorably larger.

A grinding of gears marks the approach to Porters Pass, from where the road drops into a broad basin cradled between the 2000 m ramparts of the Craigieburn and Torlesse Ranges. Grazing land carpets the valley and the lower slopes of the ranges. Here and there, jutting outcrops of rock spike the grassy hillsides, but none of them are as impressive as the strange jumbles that litter the Castle Hill area.

Upon first sighting the place, one 19th-century visitor, the Reverend Charles Clarke, described the outcrops as “grouped like the buildings of a Cyclopean city, or the circling seats of a vast amphitheatre; and further still huge groups and solitary masses like the gigantic monoliths of Stonehenge.”

Hewn by eons of rain, wind and groundwater, Castle Hill is an archetypal karst landscape, a monument to an era long past. Thirty to 40 million years ago, during the period known as the Oligocene age, much of present-day New Zealand was covered by the sea, and sedimentary rock, especially limestone, was deposited over the submerged land. But hard on the heels of this quiet period came a round of tectonic restructuring which continues to the present. The land was buckled, uplifted and subsequently eroded. Eventually, most of the Oligocene limestone was stripped away, and today only small pockets remain, one of which is Castle Hill. Even here, the sheets of limestone have been reduced to isolated blocks, pillars and outcrops, confirming that, over eons, rock is no match for a relentless trickle of water.

[chapter-break]

Ature’s Masonry always seems to thrill the human heart, and Castle Hill has long been a site of spiritual significance and artistic inspiration. In more recent times, it has become a magnet for rockclimbers.

“Canterbury’s finest crag” is how one guidebook describes the site, and, at only an hour’s drive from the South Island’s largest city, Castle Hill gets a lot of use by sports climbers. On any given weekend, it is unusual not to see a dozen cars parked at the roadside while their occupants take their skills to the rockface.

Or, in my case, take their ignorance. I am clinging to the limestone, awkward and spreadeagled, like some pathetic insect. I can neither retreat nor advance. I worked my way into this precarious situation through some deft footwork and a lunge based more on faith than skill. Now I am in a state climbers refer to as “Stay no go.” The only option is to fall. I surrender to gravity and enter the void.

Fortunately, since I am only two metres above deck, my “spotter’s” hands easily cushion the fall. That’s one of the benefits of bouldering: you can attempt precarious overhangs and mercilessly smooth faces but remain only metres above the unforgiving ground. No ropes get in your way, and although mistakes are frequent, the punishment is usually minor—a tumble into grass at worst. Bouldering also requires minimal climbing equipment: a pair of friction boots, a chalk bag, a carpet square and a toothbrush.

Carpet square? Toothbrush? I was puzzled, too, at the start. The square is placed at the foot of the boulder, and serves to keep sheep dung and slime off friction boots, and the toothbrush is for cleaning muck out of holds.

I move to another boulder, called Run and Jump Slab. Taking my cue from the name, I quickly reach its modest summit. Not for the purist, perhaps, but just my grade.

Later, as expert boulderer Ivan Vostinar leads me through a labyrinth called Quantum Field, I remark that the flattened tops of many of the boulders resemble a giant’s dental work. One conspicuous for with incurving sides reminds me of Michelangelo’s finger of God.

“It’s called the Perfume Bottle,” Vostinar tells me. We’re heading for less exalted territory: Spittle Hill, to attempt Joker.

“Only two people have climbed it before. It’s a V8, which is the hardest boulder we’re doing today. The world ranking goes up to V14, but a beginner would find even VO hard.” Vostinar’s speech betrays a slight accent: his family emigrated from Prague 18 years ago.

He walks up to the boulder, and in a series of quick hand and foot moves reaches the halfway mark Here he pauses, his entire weight held by one hand. Bicep bulging, he swings across the face for a crucial hold, and before I know it he has made the summit, leapt across to another boulder, and is grinning by my side.

“You didn’t tell me you were one of the only two who had done it,” I protest.

Diablo (V8) proves to be Vostinar’s nemesis. It is midday, and the basin is sauna-hot. “The rubber gets tacky—it’s better in winter,” he says. He is talking about his friction boots, which attain top performance at temperatures from 8-10°C. These boots have revolutionised free climbing, giving incredible grip from the most dubious of holds.

The Czech tries perhaps half a dozen times, but fails. It’s quite often like that—the whole boulder, or project, as he calls it, dependent on just one move, one handhold.

“Ever fallen?” I ask.

“Two breaks, both indoors. The moral is, don’t climb indoors.”

And why would you, when the real thing is so near?

[chapter-break]

Seeking Respite from the heat, I head for water. “Two torches, warm clothing, sturdy footwear”—so reads the sign at Cave Stream, a second reserve a few kilometres north of Castle Hill. It is such a hot day that I decide to dispense with the warm clothing, and enter the subterranean stream where it disgorges from the base of a 30 m cliff, its opening looking like something a tunnelling machine has bored.

Swallows swoop from their hidden nests in the recesses above. I feel as if I am entering the river Styx of classical mythology, said to flow nine times through “the infernal regions.”

After a few minutes I regret my heat-hastened decision to strip down, as the icy water starts to bite. I’d forgotten the viticulturist’s adage that it’s always 10°C underground. I scramble up a waterfall in the darkness, then walk quickly to keep warm. Twenty minutes later I emerge into daylight, feeling as if I’ve been through at least one of the infernal regions and am entering another: old man nor’wester hits me like a blast furnace.

Summer’s fierce heat and winter’s chill are made more intense by the dryness of the place. The basin lies in the rain shadow of the Southern Alps, and parts of it receive only a metre of rain a year, compared to four-and-a-half metres at Arthurs Pass, just 50 kilometres along State Highway 73.

Phil “swampy” Marsh has based himself at Castle Hill village for three-and-a-half years, and likes the place so much he is building a house there. Marsh works for an industrial abseiling company, and had just returned from a six-week painting and restoration job on the East Cape lighthouse when I met him.

“My work takes me everywhere—lighthouses, the Otira viaduct project, setting explosives, the Taranaki oil rigs, all sorts of crazy things.”

But it’s the recreational opportunities that have drawn him to Castle Hill. He recently obtained a concession to run a canyoning, rockclimbing and caving operation in nearby Arthurs Pass National Park.

“I’m an outdoors geek,” he admits.

Historian, amateur archaeologist and writer Barry Brailsford is another of Castle Hill’s permanent residents, attracted to the place as much for its spiritual significance as its scenic splendour. As we talk in his new house, autumnal sun streaming in through the second-storey windows, he strikes me as a spirited figure, though many have dismissed him as a maverick.

On the table a green pounamu eye, kept smooth by the oils of human touch, winks at me from within its weathered rind. The shelves are lined with indigenous people’s literature, Elsdon Best’s anthropological works, strange-shaped stones and a painted triptych of the Moeraki boulders.

Stones are important in the Brailsford lexicon. “The South Island is a waka, and it was at the centre of the waka that the most sacred stones were kept,” he tells me. “Castle Hill is at the centre of the South Island, and here limestone—the keeper of the bones—pops up out of the middle of the greywacke.”

As if to prove his theory, he points out a cup-shaped limestone feature on the skyline. For him, it is symbolic of the spirituality of the area—”the sacred nest.” We talk of ley-lines, lines of energy which have some sort of cosmic meaning to the illuminati. Marsh had told me that no less a personage than the Dalai Lama has referred to Castle Hill as one of the energy centres of the universe. For several years, New Agers have held a Transfusion Dance Party at nearby Flock Hill in summer.

Many of Brailsford’s theories arise from hundreds of hours spent with elders of a tribe which calls itself Waitaha and claims to have lived in Aotearoa for more than 2000 years—a highly controversial assertion, given that most authorities agree on a date of 1000-1300 A.D. for human arrival to these islands.

Brailsford recently published a distillation of Waitaha knowledge under the title Song of Waitaha, but its release has raised the hackles of Ngai Tahu, which is tangata whenua of the area. Atholl Anderson, a Ngai Tahu scholar, archaeologist and former professor of anthropology at the University of Otago, has dismissed the book as “daft cryptohistory” and “neomythical picaresque,” while Gerard O’Regan, heritage manager of the Ngai Tahu Development Corporation, says the iwi is furious at what it sees as misrepresentation of southern Maori tradition.

But the detractors don’t faze Brailsford, who was awarded an MBE in 1990 for his contribution to Maori scholarship and education. “We’ve got to debate these things,” he says. “The elders I have worked with give a story of this land that is far removed from what conventional archaeology—locked into its scientific paradigm—tells us. The mind and the parachute have one thing in common. I say open our minds, and bring more within the frame, and let many voices be heard.”

No one is denying that Maori occupied Castle Hill in pre-European times. One of the most important archaeological finds in recent times was made here in 1983: a backpack, found in a rock shelter. No such artefact had ever been seen before, nor had any European observer described a Maori pack.

Radiocarbon-dated to the 15th or 16th century, the pack has a circular wooden frame, over which a large drawstring bag is fitted. The highly functional design—plaited shoulder straps, frame, padding—isn’t too far removed from my own nylon pack. But to Brailsford it is more; it is evidence of kumara cultivation.

“This is exactly the sort of thing the elders described to me,” he explains. “In summer, they brought the ‘peace child’—the kumara—up from Waimaire. They were grown in baskets which were moved around, and there were up to 3000 people here during the summer.”

Canterbury Museum archaeologist Chris Jacomb says that archaeological evidence for large numbers of people occupying the area is not strong. Only two of the shelters that bear rock art show signs of occupation in their floors, and no midden remains are known from the vicinity. However, Jacomb says that archaeology “is only one of the windows we have into the past; oral tradition and whakapapa must be included to get the full picture.”

Regardless of how many frequented Castle Hill, it is unquestionably a place of special significance to Maori. In the Ngai Tahu land settlement deed, which details the 1997 deal struck between the government and the iwi, Kura Tawhiti (to give the place its traditional name) is listed as one of only 14 areas in the South Island to have a topuni—literally a cloak of dog fur, symbolising high mana—placed over it. The summits of Mt Cook/Aoraki, Aspiring/Tititea and Tutuko are also on the list, as are Kahurangi Point, Shag Point and Bluff Hill.

The topuni proclaims the sacredness of the place, asserts Ngai Tahu’s mana over it and gives the iwi a say in how it is managed. According to Ngai Tahu tradition, Kura Tawhiti means “the treasure from a distant land” and is an allusion to kumara cultivation in the area. It was also the name of one of the ancestors aboard the Arai Te Uru canoe, which sank off North Otago.

Hunting, as well as cultivation, took place at Kura Tawhiti. Stephen Phillipson of the Department of Conservation says that moa were probably hunted here, and even after they became extinct the area was still renowned as prime territory for summer harvesting of kakapo, weka, great spotted kiwi, eel and kiore.

“Maori also collected taramea, the resin from wild Spaniard plants, up here,” Phillipson says. “In the evening they would set a small fire smouldering under a bush, and next morning collect the resin off the tips of the leaves. Taramea was a very valuable commodity for trade—much more valuable than pounamu—and was used as a perfume.”

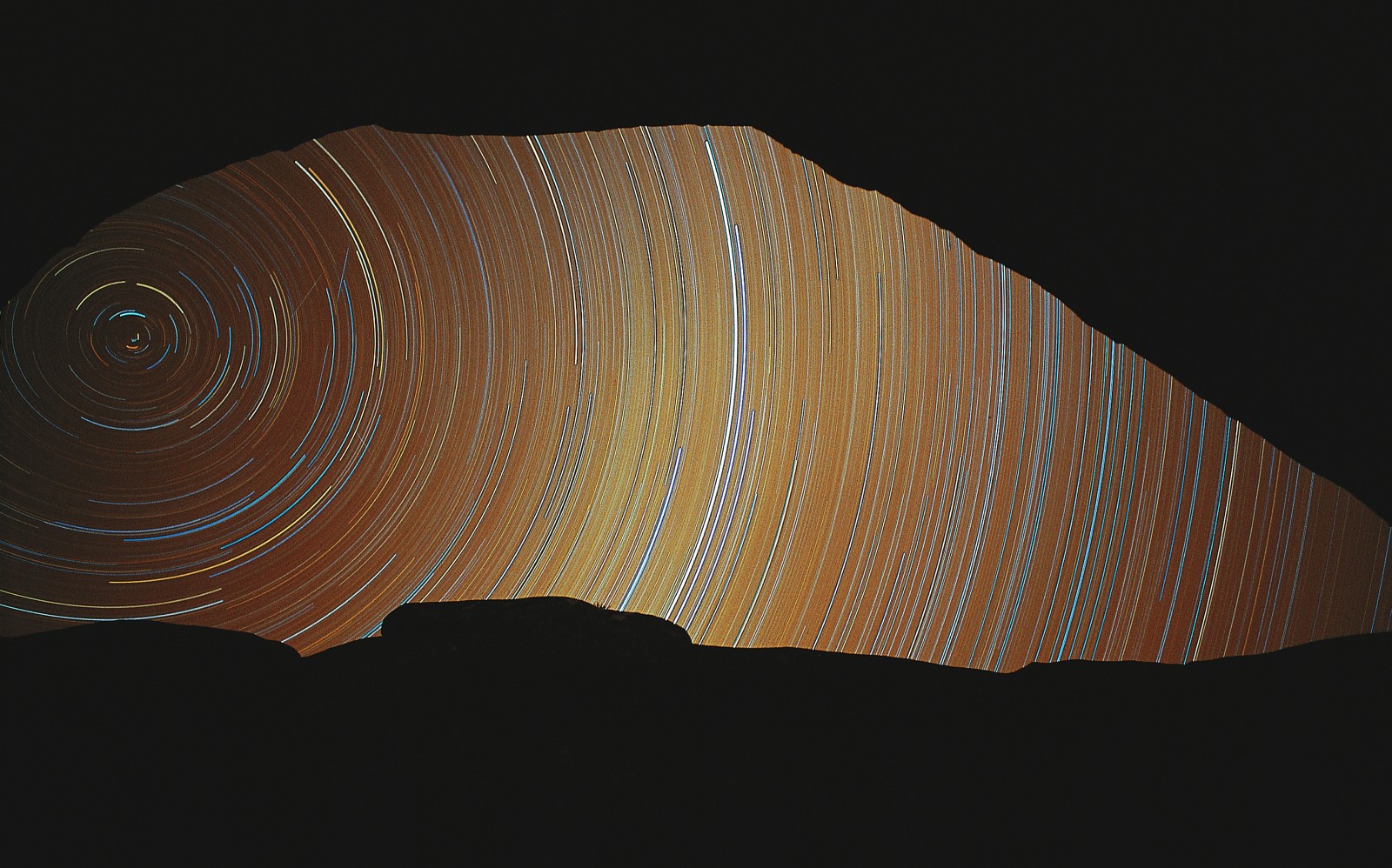

The arrangement of rocks in a landscape was also significant to Maori. “They may have aligned various limestone outcrops with particular star clusters to set their calendar,” Phillipson explains. “And although the elders are reluctant to reveal much about it, senior tohunga are thought to have lived in the area and trained their apprentices here. The cave at Cave Stream was also a really important urupa [burial place] for distinguished chiefs and tohunga. Once recreationalists started to use the area, some of the remains were removed, but others were sealed away in the walls. Make no mistake: Castle Hill is very important to Maori.”

And not just to Maori. There is a history of European land use here that has its own story to tell.

[chapter-break]

On my way back to Christchurch I call in to see Mike Bradley, the farmer who owns the land on which the 54 ha Castle Hill Conservation Area is located. He has owned the now 11,000 ha station for eight-and-a-half years, and runs 7000 merinos and 300 beef cattle on the property.

I’ve caught him at a bad time—he is about to head into the back country on his four-wheeler. Driving up the Porter Heights skifield road, I try to recollect his words: “It’s still there. Just past the quarry. You can’t miss it.”

I nearly did. A farrago of limestone blocks intermixed with rosehip and matagouri is all that greets the eye, but it holds the remnants of the homestead of the original runholders—the Porter brothers. They took up the run in 1858.

Another pair of siblings, Charles and John Enys, bought the then 14,000 ha Castle Hill run from the Porters in 1864. One of their nicknames was “buckets in the well,” for it seemed that one was always in England if the other was not.

John is the brother who has left the strongest footprint on the history of Castle Hill. As a “gentleman farmer,” he had plenty of time to follow non-agrarian pursuits, and earned a reputation as an “amateur scientist whose spelling is as atrocious as his enthusiasm is keen.” Some of his letters, held by Canterbury Museum, indicate that his interests were (in descending order): “ferns, moths and butterflies, cats, human beings, sheep.” The ranking probably explains why the Castle Hill run wasn’t a particularly successful operation.

His list makes no mention of trout, but they must have figured in there somewhere, as his diary is mainly concerned with his piscine liberations (and subsequent catches) from the Porter and other rivers. April 4, 1880, was a propitious date. “Caught first trout with fly,” the diary announces.

Among John Enys’s friends was William Izard, a lecturer in law at Canterbury College, a member of the Acclimatisation Society and a fellow angler. Izard’s diary records that one hot summer day, he walked from Springfield to Castle Hill—a distance of some 32 kilometres. Dog-tired, and his tongue like a rusk, when he reached the last creek before Trelissick (as Enys called his homestead), he found a tempting pool. As he enjoyed his soak, he noticed “three fine trout” that shared it. He tickled them up and, beaming with pride, bore them up to the homestead as an offering to his host.

“I put them there this morning,” was Enys’s terse reply.

Enys’s diary entry for February 15, 1867, sounds a macabre note: “Dug up the murdered man,” it reads. The victim, known only as Jem, was unearthed from the bed of Cave Stream. Victorian xenophobia resulted in suspicion falling upon “some Chinese with whom he was travelling.”

Such events were not uncommon. The flotsam and jetsam of Empire had washed up in the South Island drunk on cheap whisky and dreams of gold. Castle Hill was on the main thoroughfare to the booming West Coast fields, and hungry diggers stole stock or simply showed up expecting to be fed at the station’s expense.

On one occasion, a man named Levell showed up demanding meat for his dogs. The Castle Hill cook offered flour and water, but Levell remained insistent. The cook lost his temper, and in the ensuing altercation shot the man. He was charged with murder, but the jury’s verdict was “no bill.” Murderous times, the 1860s.

Another digger’s tale makes a less lamentable story. He fell between two boulders, breaking a leg. Not one to bemoan his fate, he held it out “and got his mate to chop it off with an axe.” With the aid of a stick, the digger walked on as well as ever—it was his wooden leg which had been amputated.

In 1871, Enys, perhaps hoping to both profit from increasing traffic to the West Coast and better satisfy the demand for accommodation, was involved in the building of a hotel. Big limestone blocks were shattered with gunpowder, then carted three kilometres to the construction site. Stones were cemented on top of one another, the exterior then cut smooth and the inside left rough.

Various proprietors ran the establishment. Cobb and Co., which had started a stage coach service to the West Coast over Arthurs Pass in 1866, used the hotel as a staging post. About 1900, the Midland Railway line to the West Coast was opened for passengers as far as Avoca. On the first day that the train came through, everyone left the hotel to admire the train, and in their absence the building burned down. It was never rebuilt.

Castle Hill limestone has seen at least one use that befits the spiritual associations of the area: as building material for Christchurch Cathedral. Enys donated stone for the font and pulpit, and it may have been employed more generally in interior work. On a less lofty plane, lime is still taken from the area for agricultural use.

Like his close friend Samuel Butler, John Enys returned to England later in life, inheriting the family seat in Cornwall. But he remained a man with a foot in both camps: his pride in the Mother Country was not an English rose but a garden of New Zealand natives.

John Reid, who owned Castle Hill Station during the 1970s, was a man with a different vision. He foresaw a huge increase in demand for recreational facilities in the South Island, and decided that what was needed was a mega-resort—on his land. His plan included a village, two golf courses, casino, international equestrian centre, a thousand-bed hotel, artificial lake—the works.

However, Reid had his fingers burned in the 1987 stockmarket crash, and the vision—just starting to take form as sections were sold and building commenced—foundered. Today the village comprises some 50 houses and boasts a permanent population of only a dozen, with many others coming and going.

Building regulations require the houses to be strongly built to withstand earthquake and wind, and to have steeply pitched roofs to cope with snowfall. (It is the snow that draws many here, and Castle Hill is close to five skifields.) The village boasts a nine-hole golf course—although the rabbits provide a few extras.

Although he has sold the main station, Reid continues to own a few plots in the area, and still harbours dreams of an equestrian centre and restaurant there. Early in Reid’s occupancy (1973), he imported distinctive, shaggy Highland cattle, and seeing the big animals at his Trelissick Fold—the first Highland stud in the country—was something of a treat for passing motorists.

[chapter-break]

After skiing down New Zealand’s longest run, Big Mama at Porter Heights, I collapse into the powder for a breather. The Castle Hill basin drops away to the north-east, and to the north the mountains of the Craigieburn Range stand out like a “who’s who” of New Zealand botany. The patriarchs, Cheeseman and Cockayne, loom large, flanked by Enys and Izard.

Men of science were common early visitors to Castle Hill—the names Haast, Hugel, Filhol, Potts, Fereday, Kirk, Reischek, Cheeseman, Finsch, Benham, Hutton and Thompson all appear in John Enys’s diary. Easily accessible by coach, the place was a Shangri-La for botanical explorers. The name Enys is not only remembered in the landscape, but in the plant genera Nasturtium, Ranunculus, Anisotome, Carmichaelia, and Agropyrum—all hold an enysii species.

But even in those days the botany was much altered from the cover of Hall’s totara and tall shrubs that had prevailed on the soils of Castle Hill for millennia. Maori fires almost certainly started the demise of the forest, a process which was continued by settlers clearing land for grazing. Tussock and pasture now clothe the land, but hidden amongst the limestone tors and screes are some of our rarest and most endangered plants. The six-hectare Lance McCaskill Nature Reserve, established in 1950, was the first in the country set up to protect a plant: the Castle Hill buttercup. McCaskill, a university lecturer in Christchurch, was determined to protect the plant, and took a carload of students to help him erect a stock-proof fence around the area several years before the reserve was gazetted. Hares and rabbits were excluded by a new fence in the 1960s.

Taxonomy can be a perverse business, and the Castle Hill buttercup, thought to be a distinct species restricted entirely to this basin, has recently been found to be just a variant of a widespread species, Ranunculus crithmifolius. Usually this species grows on scree, and in the gentler environment of Castle Hill it looks quite different. The leaves are larger and less divided into lobes, the plants are bigger and often greener, and it flowers more freely.

But all is not lost. The fencing has protected several other small plants that are now very rare outside the reserve. These low-growing plants—none of them more than five centimetres high—need open areas of limestone debris (protected from grazing animals), and the tilling provided by regular frost heave to keep the soil loose. (At 900 m elevation, Castle Hill has no dearth of frost.) A forget-me-not, Myosotis colensoi, is the most notable member of the group.

More small, critically endangered plants live in the Castle Hill reserve. The three-centimetre-high sedge Carex inopinata is fine-leafed, sprawling and very difficult to identify, and the grass Australopyrum calcis obtatum was described only six years ago. Both of these species grow best in partial shade, and would once have sprouted on the floor of the forest and shrublands, so a modest revegetation programme has been initiated in the past five years to establish a more conducive habitat. ShrubsMyrsine, kowhai, Coprosma, native brooms, Olearia, Griselina, kohuhu—are being established (with difficulty), and totara will be planted once the shrubs are thriving.

Only two mountain totara remain in the whole area—very distorted specimens perched atop boulders at Gorge Hill. Each is conical, with a trunk about a metre wide at the base, tapering abruptly to give a tree less than three metres high. Cuttings from this pair will form the core of the new totara plantings.

At Cave Stream Scenic Reserve are more fenced-off areas, protecting further rare plants. Unusual plant communities are growing here on a glacial outwash terrace, a river terrace and the steep rise to a river terrace—all, according to Stephen Phillipson, quite distinct assemblages.

“The four-hectare Enys Scientific Reserve on the glacial outwash terrace was fenced against rabbits and hares to protect bog pines, but serendipitously the area contained five specimens of the very rare Hebe armstrongi,” says Phillipson. “We collected seed and were able to raise and return 200 more plants to the reserve, which is great because three of the original five have since died. We are also trying to establish this plant in the Cave Stream Reserve.

“On the river terrace are two more rare plants, Hebe cupressoides and the broom Carmichaelia kirki. Although Carmichaelia is a broom, it is the only member of the family to grow like a vine—it’s most odd. We’ve had to fence hares out of this area, too. The riser community contains the Carmichaelia and also the extremely rare Helichrysum dimorphum.”

Ann Shepherd, a DoC worker from Arthurs Pass, describes the Helichrysum as “the ugliest plant you’ve ever seen. Even when it’s in full health it looks dead.” Unlike most of Castle Hill’s other rarities, it has the ability to survive rabbits and hares—but not, alas, sheep.

Probably no other place in the country has such a concentration of small reserves protecting rare plants.

[chapter-break]

F the plants are hard to spot, Castle Hill’s rock art is even less obvious. “Most drawings at Castle Hill are barely recognisable,” says Chris Jacomb, handing me the results of an inventory of rock drawings and shelters recently carried out at the site.

In 1993, Jacomb was part of a survey team which investigated old reports of drawings and shelters. Most were found, and some new ones showed up. A couple had mysteriously disappeared. An old photograph depicting a highly stylised figure spearing a tuatara-like creature catches my eye. “A hoax,” Jacomb tells me. “It was rather different to anything seen anywhere else—probably done with charcoal, which soon washed away.”

Strangely, John Enys and Julius von Haast, Canterbury Museum’s first director, never documented the Castle Hill rock art, although Enys found adzes (which he called tommyhawks) and some “rough knives of hard flaked stone.”

Of all archaeological matters pertaining to Maori, rock art has been the most controversial. The Dutch painter Theo Schoon described the dogs, fish, birds and bird-men that form the main subjects of this art as “frozen poetry.” The most easily recognised and prevalent are human figures—frontal silhouettes with flexed limbs. Almost all South Island rock art has a strong family likeness. Facial features are almost never shown, as if the subjects were universal. Artists used charcoal or ochre, and more rarely the rock was carved or scratched.

Haast considered them the work of “pre-Fleet” or even non-Polynesian visitors, due to the marked divergence between most drawings and traditional Maori wood carvings. This scepticism was deepened by the apparent lack of an oral history of rock art held by 18th-and 19th-century Maori. Diverse theories were proposed from their apparent likeness to works of other cultures. They were variously attributed to shipwrecked Tamil seafarers and Buddhist missionaries. They even rated a mention in Erich von Daniken’s Chariots of the Gods.

Such flights of fancy have been debunked by zealous archaeological study over the past two decades. Excavations of shelter floor deposits coupled with radiocarbon dating have established rock art as an important part of early Maori culture. It is thought that the great majority of drawings were carried out in the first few centuries after arrival.

Some of the art is of more recent antiquity, and clearly depicts European sailing ships and people riding horses. The intent behind the pictures is unclear, but it shows that southern Maori maintained its rock art tradition through to historic times.

Limestone overhangs also provided shelter for early European stockmen and travellers. Some exhibit drip lines—grooves chiselled along roof overhangs to channel water so that it drips off the point instead of running into the cave.

Between the crags known to rockclimbers as Quantum Field and Dark Castle is a gully, at the bottom of which is an old stockyard site. Nearby, a man-sized boulder has been cleanly sawn, and on its cut face are autographs from days of yore. “O’Malley” and “Milliken” were Irishmen who grew oats for the West Coast wagon and coach horses. Inscribed above is a more famous name, a barely legible “Haast,” son of Sir Julius. Julius Herman Haast owned the Castle Hill run for a year in 1897.

The weathering of these deeply grooved monikers makes it all too clear why Maori rock art is so indistinct. And the graffiti of today—profound etchings in the vein of “I waz hair,” sadly noticeable on some rocks, is destined to go the same way. In geologically stable Australia and Africa, rock art has survived tens of thousands of years, but New Zealand’s dynamic environment makes rock a poor canvas for human paintings.

On my last visit to Castle Hill I follow in Izard’s and Enys’s footsteps. I trace an ancient river terrace to where Broken River cuts its gorge downwards towards the Waimakariri. As I wade upriver, the hills hem in close, almost forming a box canyon. The limestone beds here are not cream, but grey, coloured by ash from primordial eruptions. I catch one of Enys’s progeny from the Porter’s rushing waters, while, overhead, jets boom by Australia-bound. Hanging on the horizon, the sun is like an over-ripened grapefruit. Its last rays light the cliff ramparts, giving an almost Badlands feel to the scene.

“Every stone has a story.” Barry Brailsford’s pleonastic words ring in my head. I leave Castle Hill sceptical about ley-lines, but after clambering up boulders, dragging myself through the Stygian recesses of Cave Stream and feeling the tug of a strong rainbow trout in the Porter’s rushing waters, I feel I know why this area is so special to Maori and Pakeha alike.

These limestone tors—my finger of God, Vostinar’s Perfume Bottle, Brailsford’s keeper of the bones—are no mere castles in the air.