Looking for the good life

Throughout the country, people are forsaking city and suburb to move back to the land. Making money isn’t the drawcard—returns from farm products are meagre. Rather, these emigres are flocking to smallholdings in the hope of establishing a more agreeable lifestyle, one in which the pressure of urban work can be offset by the gentler rhythms of nature. In the Hokianga, Miriam Tyler strolls among her grove of 100 walnut trees grown from select seed to provide valuable timber some decades hence.

Suddenly, reality was very different from all the dreaming and planning. The cattle truck was backing into the gateway of our newly acquired property on the outskirts of Masterton, about to deliver our first batch of heifers. Would the sagging fences contain the animals? Was there enough grass for them? Would some poor beast break a leg as it was prodded out of the truck onto the rock-hard summer ground?

I turned to my wife, Diane, to share my mounting doubts about the absurdity of swapping our comfortable suburban life for the challenge of establishing a smallholding from scratch, but she had taken refuge behind one of the few trees on the property, a forlorn, lightning-struck totara. We were not farmers. Whatever had possessed us to think we were?

Sixteen years later we’re still at “Ranginui,” our 9 ha rural haven, now divided into 12 paddocks stocked with cattle, sheep, hens and kune-kune pigs, and with hundreds of trees bringing shade, shelter and a diversity of birdlife. Diane has overcome her fear of animals, but I’m no more practical than I ever was, and a mild panic still sets in if a fence wire snaps. I console myself with the thought that we provide plenty of work for contractors.

It is mostly townies like us who have fuelled New Zealand’s smallfarming revolution. We are the ones who have harboured the dream of owning some country acres—of waking to the “quardle oodle ardle wardle doodle” of magpies rather than the hum of thousands of cars converging on city parking buildings. And for increasing numbers of us, that dream is coming true.

Fly in a small plane over the edges of any New Zealand city and you can look down on a scene that has changed markedly during the past 20 years. There has always been, of course, a patchwork of market gardens and orchards serving city needs, but now, spreading outwards in ragged ripples, thousands of new dwellings—from kitset homes to mansions—sit on smallholdings where an impressive array of animals and crops are grazing and growing.

There are regional differences dictated by such factors as population pressure, level of affluence, the quality of roads, and local-body attitudes, but smallfarming is playing an increasingly important role in the rural economy from one end of the country to the other.

And it is not just the economy that has benefited. The influx of new people into rural areas has breathed life into the sometimes foundering communities where they settle—keeping schools open, revitalising social groups and boosting contract work. The sale or subdivision of traditional farms has also allowed many farmers to escape the crushing burden of unsustainable mortgages.

Ministry of Agriculture estimates, Quotable Value New Zealand figures, regional authority and local council data and a little educated guesswork put the number of smallholdings (between one and 40 ha) in New Zealand at well over 70,000, and growing fast. Real-estate agents put the total even higher, at 100,000. The number of smallholdings is steadily nosing ahead of large farms at a time when 360 ha and 3000 stock units is considered a barely viable farming enterprise.

Not surprisingly, smallfarming is largely a middle-class activity. Land close to cities and towns is expensive, and the cost of building even a modest house with water collection, sewerage and connections to power and phone is higher than in town. As the return on this considerable capital investment is generally minimal, smallfarmers must either have a sizeable nest egg or salaries substantial enough to meet the hefty outgoings.

Since 1984, middle-class New Zealand has prospered under successive Labour and National governments. The number of self-employed has gone up steeply, and there are more well-paid consultants in the computer and communications industries than ever before. Here, as in similar economies overseas, the more prosperous are deciding where and how they will live, and for growing numbers this is not on pocket-handkerchief urban sections.

New Zealanders have always felt a strong affinity with the land. Many of our forebears were farmers, and we may recall with affection and nostalgia childhood holidays spent on farms. Our attachment to the suburban section and home ownership has been stronger than almost anywhere else in the world. Perhaps urban in-fill sections little bigger than cemetery plots have finally become too small to meet an inchoate need for our own patch. And although small rural blocks are more expensive than a suburban section, they appeal to a sense of value for money: for perhaps 25 to 50 per cent more than the cost of an equivalent house and minuscule section in town, you get a house plus 60 times as much land!

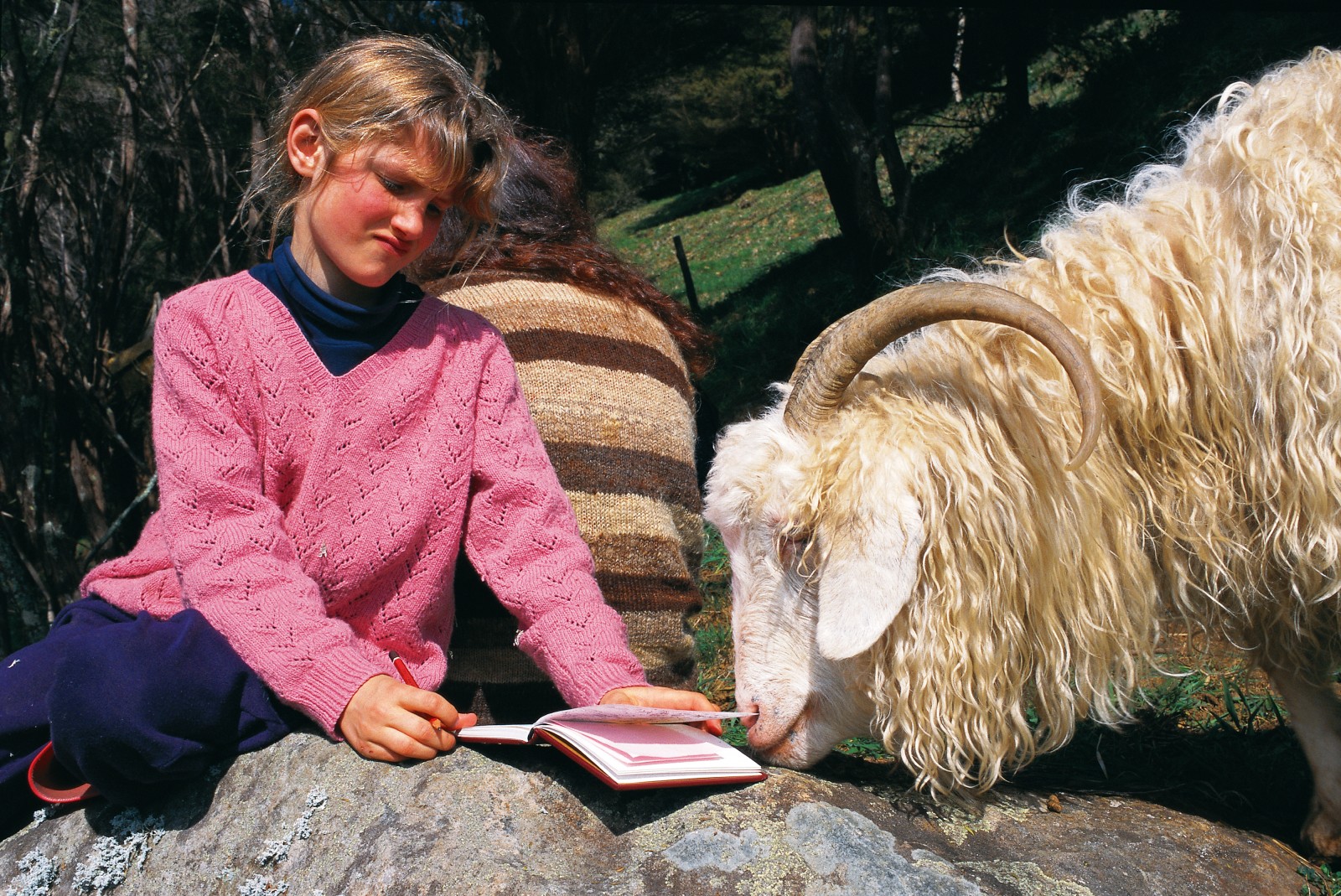

Also influencing the move to rural pastures is the thought that the country is a better place to bring up children—an idea that frequently tarnishes as they age.

A strong sense of community is also cited as a benefit of country living, although, paradoxically, many people head to the country to escape the press of urban neighbours.

Regardless of why we go, the important thing is that we are going. Between 1991 and 1996, there was, after decades of rural population decline, a 9 per cent increase in the numbers of Kiwis living in country areas, including small towns. It is a trend being repeated in the United States, Canada, Australia and the United Kingdom.

Green acres are calling us.

[chapter break]

What, then, is a smallfarmer? “A vertically challenged agriculturalist,” runs the well-worn joke. While names like “smallholder” or the American “homesteader” might be less obvious butts, they are really no more descriptive. “Toy farmer” is obviously derisive, while “hobby farmer” rather unfairly equates small-scale farming with stamp collecting or restoring old cars.

It seems, in fact, that the term “smallfarming” is as much an attitude of mind as a fence around a given number of hectares. Pamela McDowell’s quarter-acre section in one of Lower Hutt’s most exclusive streets swarms with beehives, hens, a worm farm and raspberry and blueberry patches. Sales from her produce, including bagged organic compost, supplement other income from bottling pickles, chutney and relish and caring for several elderly people. She considers herself a smallfarmer.

Gary and Emily Williams’ 50 ha property in the Horowhenua, where organic sheep and cattle graze and many species of timber and firewood trees grow, is larger than the usual smallholding but they, too, consider themselves smallfarmers.

When attendees at a 1997 smallfarming conference were asked to describe how they perceived themselves, the responses reflected an emphasis on farming over lifestyle: “A person with an affinity for living/growing things and the earth that produces them,” said one. “A small-scale intensive and efficient primary producer,” said another. “A less traditional land user, usually in it for love,” announced one financial realist. And even more succinctly: “A person with a lot of hope and a big pocket.”

John Fairweather, of Lincoln University’s Agribusiness and Economics Research Unit, defines smallfarmers (or smallholders, as he categorises them) as people who have a commitment to effective land use, and who earn at least some farm income. They differ from a group he calls “lifestylers”—a term derived from the ubiquitous “lifestyle block” dreamed up by real-estate agents when they began to sell the concept of country living 20 years ago.

“It’s my guess that there are about five times as many lifestylers as smallholders,” says Fairweather. “The large houses they build are the tangible signs of their urban success. Generally, lifestylers retain their urban ties to a greater extent. They’re usually not going into the countryside to be rural; they’re in the country and remaining urban.”

Not all urban escapees are wealthy, however. Sometimes young families move to rural areas because the deposit on a few doubtful hectares and an old house moved off an inner-city section can be a route to relatively inexpensive home ownership. In some parts of Auckland’s lifestyle block zone, as many as half of the houses have been transported in, leading to a curious mix of styles.

Complicating the issue of terminology is the fact that some lifestylers also have agricultural aspirations. Canadian expatriate Lorne Kuehn, who, with his New Zealand wife, Pamela, lives on 40 windy hectares on the shore of Lake Ellesmere, has coined his own term for the farming activities of well-heeled lifestylers. “I call it ‘vanity agriculture,” he says with a chuckle. “Vanity farmers are the lawyers, stockbrokers and airline pilots keen to affect the genteel English manor lifestyle, with a few expensive animals dotting the grounds as attractive talking points. Did you know, for example, that, their scarcity and present marketability aside, an alpaca’s lifetime of fleeces is worth about one-tenth what you pay for the animal?”

Lorne has the good grace to grin as we sit in a shady part of the garden that surrounds the 22-room mansion that was once one of the area’s premier homesteads. Across a paddock or two, just out of sight, is an impressively large herd of alpacas.

Lorne, who had wanted to farm for as long as he could remember, chose to retire at 45. This caused some consternation, as he was Canada’s head of scientific intelligence at the time. It was an early example of the “cashing out” phenomenon. Successful real-estate investment and patents to several inventions provided the wherewithal to buy Waitangi Estate and to spend a New Zealand-sized fortune renovating the house and reviving the farm. With energy and enthusiasm, as well as a nod in the direction of a very conventional local community, the Kuehns grew lucerne seed, ran sheep and cattle, sold hay, planted a woodlot. “But we were appalled to discover that you simply can’t make any money from conventional farming in New Zealand,” he says.

The Kuehns’ response was to diversify more and take a niche approach, focusing on rare-breeds farming. The result is exotic: alpacas, llamas, belted Galloway cattle, Enderby Island rabbits, miniature horses, Shropshire and Arapawa sheep and a hazelnut orchard and vineyard thrown in for good measure.

“We know of other smallfarmers with more limited resources who’ve developed successful economic niches like a hectare of flowers or breeding horned sheep for hunting,” Lorne says.

[Chapter break]

Smallfarmers differ in their level of affluence, but they share many fundamentals. They all complain that there aren’t enough hours in the day, because they almost all work off their properties, whether that means jetting the world or driving to town. They invariably moved to the country to enjoy the pluses of country living and escape the urban minuses, but few are so dewy-eyed about Arcadia that there is not some level of economic intent as well. It might be crucial to day-to-day living or the comforting thought of a retirement cushion.

Generally, smallholders scrimp and save, and often make sacrifices to buy their properties; they rarely inherit them. They usually come to smallfarming after varied, often successful, careers in a number of fields, although some have farming in their genes. While many are not in it for the money, it would be the rare or poorly run smallholding that did not cover the rates, achieve a degree of cost-saving self-sufficiency and fund work that enhanced a property’s worth.

A 1994 survey conducted by Country Living, then the magazine of the New Zealand Smallfarmers’ Association, in which 178 smallholders completed detailed questionnaires, adds more facets to a profile of the smallfarmer. Only 45 per cent of their properties had been subdivided from existing farms; 62.5 per cent had mortgages; 61 per cent of respondents and 77 per cent of spouses worked up to 20 hours a week on their properties; 35 per cent earned less than 10 per cent of their income from smallfarming; 71 per cent were employed off their properties, with 47 per cent in full-time occupations; 73 per cent of spouses worked off the land, 48 per cent of them full time.

Main farming activities in 1994 were: sheep farming (39.5 per cent), cattle grazing (36.5 per cent), dairy beef (21 per cent), calf-rearing (18.5 per cent), horticulture (13.5 per cent), trees for timber (12 per cent), pigs (11 per cent), and tree crops, particularly walnuts, chestnuts and olives (7 per cent). As many as 79 per cent of respondents had achieved partial self-sufficiency, and 49 per cent had aspirations of complete self-sufficiency. Twenty-four per cent farmed organically or biodynamically, and these were goals for 44 per cent more; only 8 per cent used chemicals “widely,” while 83 per cent applied them “sparingly.”

For some, smallfarming is a livelihood after redundancy, or the opportunity to revel in a peaceful, multifaceted retirement. Others take a particular pride in self-sufficiency, see smallfarming as their superannuation scheme or thrive on the challenge of a second smallholding after taming the first.

In a number of ways, Dick and Lyn Bennett are model smallfarmers. They manicured a scruffy, flat two-hectare corner of an Otaki dairy farm into a model diversified smallholding in the 1980s, and were quickly self-sufficient with an abundance of home-grown mutton, lamb, beef, pork, eggs, vegetables and fruit. In 1994, with literally nothing left to improve on their property, they moved to a hilly, gorse-choked 5.2 ha property near Tauranga.

With Lyn eligible for superannuation, Dick took early retirement from his engineering business to lick this more exacting challenge into shape, and five short years later the Bennetts are beginning to ponder another move, probably one more in keeping with the inexorable passing of time.

“We just couldn’t imagine living any other way,” says Lyn. “And we live wonderfully well on what we produce, our superannuation and quite meagre savings.” It’s not always the case, but Dick’s make-or-mend-anything abilities and the pair’s hard work have also meant they have significantly increased their capital assets since beginning the smallfarming life.

There are a number of successful single smallfarmers, such as Yvonne Jansen, a retired naval officer, who planned and ran a goat-rearing smallholding on the outskirts of Masterton with military precision for a number of years before deciding that the rigours of full-time employment—necessary to keep the farm going—were destroying her enjoyment of country living. Now in town, she dreams of another smallholding when her second career, as matron at a girls’ school, comes to an end.

Generally, though, smailfarming is a partnership, and when both partners work off the property, which is often the case, a division of duties is essential. Smallholders tend to carry out routine chores during weekday mornings and evenings and use weekends to develop their properties.

Long daily commutes between farm and town can be a wearying fact of life for smallholders, but Laurie Callender manages to put the 60 km drive between Kaukapakapa, north-west of Auckland, and the city to good effect. As sales manager of an Auckland car company, he uses the travel time to iron out any problems in the new-model Volvos he sells. The traffic also gives him ample time to plan weekend work on the property, which also includes repairing chainsaws for neighbouring farmers.

plenty of rural chores, such as clearing thistles, regularly confront her, she considers that the move to a less stressful existence has saved her health.

Far as Callender travels, others are willing to face even longer commutes. According to Wayne Hastings, a real-estate salesman in Paparoa, a township on the Kaipara Harbour, there has been an explosion in rural subdivision development in the past few years. “We’re the ‘last frontier’ as far as Aucklanders are concerned,” he says. “The local district council has a more laid-back attitude to subdivision compared with Rodney, to the south, and, with plans for more northern motorway extensions, we’re going to be less than two hours away from Auckland, at the outer limit of the distance people are prepared to travel.”

Hastings is selling bare 4 ha blocks at up to $200,000 each. He says that many of his buyers are in the computer business and plan to work from home or travel to the city only once or twice a week.

Not far from Paparoa, Otamatea Eco-Village is promoting a very different sort of lifestyle. It is a community rather than a subdivision, and 15 unit titles are being sold, each consisting of a freehold 2 ha block and a one-fifteenth share in 70 ha of jointly managed common land. With a base purchase price of $80,000 per title, the firstcomers, some already building their “visually compatible” homes, have middle-class occupations and resources, and a commitment to permaculture principles. Their vision is to “create fertile, holistically integrated agricultural systems and a village culture.”

In the South Island, smallfarming may be helping stem the population drift northwards. Dunedin City’s rural development officer, Jon Muirhead, has the job of encouraging new farming activities with sufficient potential to maintain the economic viability of Otago’s hinterland.

[Sidebar-1]

As the emphasis has been on intensive horticulture, with crops such as gentians, gevuina nuts (cool-climate cousin to the macadamia), hydrangeas and peonies, which thrive in the region’s longer daylight hours and colder winters, the seminars and information service he offers have attracted a disproportionate number of smallfarmers.

With gentians, for example, three-quarters of the growers are smallfarmers who hope to supply cut flowers to the Holland, Japan and the US. Sixty thousand plants have been established in the region over the past 18 months.

One of these growers is Ruth-Ann Anderson, who has developed, with her husband, Dave, an immaculate smallholding from an untidy 3.6 ha contractor’s yard down a blind lane on the outskirts of Mosgiel. In addition to sheep, goats, pigs and sufficient hens to generate gate sales of 6-7 dozen white, brown (and green!) eggs a day, Ruth-Ann, a horticultural science graduate from Lincoln, has 4000 gentians planted, and will begin exporting blooms this year.

[chapter-break]

Not every smallfarming venture flourishes as vigorously as the Andersons’ gentian patch. Vicki Hay, who lives with her family on a 4 ha property near Mosgiel which, with its impressive stables and barns, might have been lifted out of the Kentucky countryside, made no attempt to hide her disillusionment when I walked with her around the property.

A small-scale horse breeder, she had been running up to 10 horses on the property, and, despite one showjumper selling in the US for $30,000, found occasional sales barely covered the daily feed and other costs. She helped pay these overheads and upkeep on the property by working as a research company organiser, with hours fluctuating between 20 and 60 a week. Time was at a premium, and horses are not easy-care animals.

“Apart from feeding and watering, it takes 10 minutes every day to dung out each horse’s area,” she said. “Increasingly, it’s time we simply don’t have.” She started to see the ever-mounting manure heap as more of a problem than a marketing opportunity.

Several months later she described her attitude as cynical more than disillusioned. “Some people have totally unrealistic views about living on a smallholding,” she told me. “I get tired of hearing how lucky we are to be here when they have absolutely no idea of the time and costs involved.”

Hay has taken decisive action to cut back her working hours to 20 a week and to reduce the number of horses, cross-grazing them with less-demanding sheep. “We may even have the time to enjoy it here a little more,” she added hopefully.

Financial troubles can cause a smallfarming venture to come unstuck just as easily as they can sap a traditional farm of equity. Relative to large farms, production costs on a small block are high—and are not always appreciated at the outset. A 10 ha farmlet requires many of the same infrastructural components as a 500 ha property—yards, water supply, electric fences, farm bike, posthole borer, fencing tools and much more. The smallfarmer will buy herbicides and drenches in small, relatively expensive amounts, and when stock are purchased there will only be a few on the truck, yet the delivery cost will be the same as if the truck were full of animals. To the 500 ha farmer, 10 ha is just one more paddock.

Kaukapakapa vet Tom Henderson, who calls on many smallfarmers and owns 20 ha himself, considers that those who live on larger smallholdings with traditional stock—sheep and cattle—have a hard time of it. “You can’t make a useful amount of money from 20 ha around here, so you have to have some other job,” he says. “But the tasks you have to do on your land are pretty similar to what is required on a full-sized farm. There may be fewer cattle in the mob, but you still have to move them just as regularly. Sheep have to be crutched and drenched and shorn just as often whether you have 50 or 50,000. Because most of your time is occupied with earning a living, all your ‘spare’ time is needed to stay on top of the farming operation.”

Time and money aren’t the only obstacles to be surmounted. For the newcomer to farming, being suddenly confronted with hectares of fast-growing gorse and thistles, and animals much larger and more intransigent than they ever appear in books or from the windows of passing cars, can be daunting to the point of despair. There is a lot for the neophyte farmer to pick up, and most of this knowledge and skill has to be gained on the hoof.

Many hard lessons are learned, and sometimes the only consolation is that you can laugh about them in hindsight. One budding smallfarmer tried to wean his first two calves from their mothers by keeping the normally placid cows behind an electric fence on the roadside in front of the house, while the two calves were placed in the most distant paddock. The first hint that all was not well came next morning, when his wife, feeding a baby in the lounge, heard an ominous plopping emanating from the far end of the house. One of the cows, anxious to find her bellowing calf, had broken through the fence, trotted along the drive, and pushed into the house through an open ranchslider. Unsettled by confining walls and unfamiliar carpet, she gave vent to nervousness in time-honoured fashion. The term “house cow” took on a new meaning for this family.

Much of the work on small blocks is hard and not particularly pleasant. De-horning cattle is always a gory business, and scraping maggots from the fleeces of flystruck sheep is far from enjoyable. Clearing hillsides of gorse (which seems to regrow almost as fast as it is cut), pruning large stands of pine, spraying thistles, erecting new fences, planting trees—all can be thankless and exhausting tasks.

But there is great satisfaction, too. The fence may have taken three weekends to complete, but it is ruler straight across the land, and should contain animals for at least the next 20 years. The block of trees that was such an effort to plant is growing well and will beautify a steep gully for perhaps another half-century. Fat, contented, healthy stock, enhancing the richness of the landscape, will fetch top prices at the next sale. These are the real rewards of those who work the land—to smallfarmers no less than their larger neighbours.

[chapter-break]

So, how is the smallfarming revolution affecting life in rural communities? Developments in picturesque Gladstone Valley in the Wairarapa typify a countrywide phenomenon. Long-time resident Ian Stewart wrote about the valley in two 1993 issues of Country Living. “What happened to our immediate neighbours, a number of whom had been seduced by SMPs [supplementary minimum prices] and other government initiatives to increase their indebtedness, is similar to the pattern that developed throughout the country,” he wrote. “The influx of smallfarmers has been significant in two ways. Most importantly, the infusion of new capital and relatively high prices paid for small blocks, particularly those with surplus houses, has allowed farmers to stay on their land and even ensure farming livelihoods for the next generation. Secondly, the increase in population and the diversity of new skills and interests that have entered the area have invigorated and enlivened the community.

“Today there are double the number of people living on and off the land in the part of Gladstone I’ve been describing that there were 20 years ago. Two decades ago there were about 10 property owners and farm staff and their families. Today there are only two permanent farm workers (and three self-employed workers in their own or rented houses), and over 20 farm/farmlet-owning families. One third of the residents have come from outside the area, mainly during the last decade.”

Gladstone’s renewal, which included a $180,000 sports complex and community centre, was particularly obvious at the school. In the early 1980s, the roll had dropped to close to 50, and the school was facing an uncertain future. In 1993, there were 100 pupils and five staff.

“Our roll is still growing slowly, and reached 119 at the end of 1998,” says Gladstone principal Kevin McKay. “It’s particularly noticeable that most children starting here are in the 8-10 age range—that’s about the age children are when their parents can afford to move onto a smallholding. In 1995, 70 per cent of enrolments were children from traditional farms and 11 per cent from smallholdings. This year, 42 per cent are from small farms and only 34 per cent from larger properties.”

Gladstone’s growing reputation as a premium wine-growing area second only to Martinborough in the Wairarapa has not blunted the demand for smallholdings. District plan changes have also made it easier for farmers to offer prospective buyers a wider range of small lots.

Twenty years ago, a holding needed to be 25 acres (10 ha) in order to comply with the Wairarapa South County Council’s economic unit strictures. In 1998, one of the area’s most recent urban émigrés, Louise Walker, bought a 1 ha smallholding with a 1930s farm cottage overlooking Gladstone. An Auckland magazine advertising manager in her late 40s, she decided it was time to leave an increasingly stressful life behind her. Louise has thrown herself into remodelling the cottage and promoting its homestay potential, is immersed in the local community and has ambitions to market lavender.

“It’s been a gigantic step for me, moving 600 km from a well-established career and most of my friends, but it’s also been a lifesaver,” she says. “I don’t know how much longer I could have survived in Auckland without serious health problems.” Not that the move to the country has been entirely stress-free. “One of the frustrations of living alone is that some things simply can’t be done without the application of more brute strength than I can manage,” she says. “And with everything from the house onwards costing more than I’d planned, I’ve had to go back to selling advertising space part-time.”

While the interest in smallfarming has often proved a boon to struggling traditional farmers willing to lop a few hectares off their properties, not all farmers have greeted the arrival of the newcomers with enthusiasm.

Some in the Gladstone area believe the rapid increase in the number of smallholdings in the Carterton district, which now allows rural subdivision down to 3 ha by right, will affect farm production. One concern is that incoming smallfarmers can, under resource laws, object to, and possibly stop, rural practices they don’t like. There is concern that smallfarmers will be unhappy about smells from nearby piggeries or the noise of dawn-to-dusk aerial topdressing, after-dark use of bird scarers and night-time crop harvesting.

“I know of two cases where lifestylers have complained about aerial topdressers flying over their houses at dawn,” says long-time Gladstone farmer Rex McKay. “We need to protect the rights of existing landholders to carry out our farming activities as we always have.”

Lincoln’s John Fairweather believes such niggles are the exception, and that most smallfarmers adapt quickly to the rural scene and enjoy the experience. In a 1993 report, “Smallholder Perceptions of the Rural Lifestyle,” based on a study of intending and existing mid-Canterbury smallfarmers, he wrote: “There was no evidence found to support the hypothesis that a significant number of smallholders were dissatisfied with their rural experience. . .

Nearly all smallholders intended to enjoy the lifestyle for as long as possible. There was no significant migration back to the city.”

And there have certainly not been the recorded cases in New Zealand—as there have in Britain and the United States—of rural newcomers being driven back to town by unfriendly natives, the cacophony of country noises and the pungency of agricultural odours.

“You do hear talk about the ‘parasitic bed-and-breakfast brigade,’ townies who come out, build flash houses, sleep there, have breakfast and then rush off to town,” says Richard Johnson, district planner of the Waimakariri District Council. Not one to take anything for granted, he carried out research in his booming district and found that genuine criticisms and concerns were practically non-existent. Contrary to the loudly voiced opinions of the few, lifestylers were heavy users of local services.

[chapter-break]

Laurie callender, a former president of the NZ Smallfarmers’ Association, has no doubt about the contribution smallholders make to a community. “Apart from the huge financial difference it’s made to some farmers to sell parts of their farms to smallholders, I’ve seen ample evidence around the country that the two groups complement each other very successfully,” he says. “Large farmers are generous with advice and the loan of machinery; smallfarmers can often show that a new crop or animal diversification does really well in an area.”

He points out that genuine smallfarmers are committed to improving their properties. “Smallfarmers aren’t part of the ‘big house, small pony’ brigade,” he says. He also adds, a little wryly, that smallholders are often deeply enmeshed in the local community. Soon after the Callenders moved to Kaukapakapa, Jan was secretary of the local Women’s Division Federated Farmers, vice-president and health officer of the Kaipara provincial WDFF, secretary of the ratepayers’ association and on the local community hall committee.

And at least a few smallholders find they so enjoy the challenges of farming that they use their blocks as stepping stones to becoming full-time, large-scale farmers.

Some prejudices do remain, though. Smallfarmers are sometimes criticised for treating animals poorly, usually because of inexperience or ignorance. Committed smallfarmers believe these attacks are sometimes as much to do with concern about the spread of smallholdings—anathema to some traditionalists—as animal welfare issues. “Genuine smallfarmers don’t like to be lumped in with people who have a few acres and as many animals for decoration,” says current Smallfarmers’ Association president Ray Toms. “Smallholdings are easy targets because they can usually be seen from the road. We don’t hear anything about the awful neglect of, for example, flystruck sheep that goes on out of sight in the back paddocks on large ‘easy care’ farms.”

Simultaneously, smallfarmers are ridiculed for treating stock like pets. It is certainly true that most smallfarmers still carry out the “lambing beats” now abandoned by many large farmers, who operate on survival of the fittest principles. Lambs bottle-raised in the kitchen do become members of the family, and if you make the mistake of naming them as well they are destined to wind up as lawnmowers, not roast dinners.

[chapter-break]

The Beguiling compensation for the winds that sweep across Andy and Sue Barratt’s hillside property near Karitane, north of Dunedin, is a spectacular coastal view. The Barratts have planted half of their 17 ha with 4000 varied trees in hedgerows and clusters to provide a sympathetic microclimate for 200 hazelnuts that will come into full production in eight years’ time. Their endeavour has challenged local assumptions about land use.

“At the beginning the locals thought we were mad,” says Sue, “but when they saw how hard we worked and the difference the trees began to make, they admitted that it was pretty marginal land for sheep.”

The Barratts are not alone in thinking outside the agricultural square. Over the past two decades, New Zealand smallholders have been among the most innovative and successful farming experimenters. Dairy and fibre goats, emus and ostriches, alpacas and llamas, angora rabbits, chestnuts, hazelnuts, walnuts, olives, herbs and lavender have all begun their sometimes chequered histories on smallholdings. This is not really surprising, as smallfarmers are not usually financially dependent on the success of their farming operations, so are more likely to take leaps into the unknown than are their big-farm cousins. They are nonetheless still interested in finding ways of making small acreages pay, and their efforts often point the way to future farming opportunities. Smallholdings can be seen as demonstration plots that give large-scale farmers broad hints about diversification options that really do work in a particular part of the country.

Some smallfarmers have chosen not to innovate, but to capitalise on their proximity to established markets. A number have done well by supplying specialist vegetables or garnishes to the booming city restaurant trade. Others are fulfilling a growing demand for medicinal herbs. One smallfarming family breeds butterflies to order. Another grows palm trees for beautification projects around much of the North Island.

Such niche activities may seem quaintly old-fashioned and hardly part of the economic mainstream, but appearances can be deceptive. Next century, to paraphrase Charles Handy, the noted British business philosopher, most people won’t have conventional jobs. Instead, they’ll have customers for the products and services they provide. Smallfarming, in terms of a vocational model, may turn out to be the next millennium’s status quo.

There are common strands running through the lives of New Zealand smallfarmers. More than anything else they are individualists who had the courage, energy and persistence to take their dreams further than an envious flick through the pages of Growing Today. Most feel that, symbolically at least, going smallfarming has been an attempt to take more personal control over their lives in a world where this is becoming increasingly difficult.

Certainly, things don’t always go according to plan. Weather is a wild card, capable of undoing the work of months or years in a single hailstorm or flash flood. Even an average winter can bring days of continuous rain, when lakes surround the house, and cattle, like 600 kg rugby forwards, churn the soil to deep mud.

The compensations, however, are manifold. Beginning to notice nature’s subtleties is one: nuances of weather changes, social interactions amongst a herd of animals, the way a bird prefers berries from one tree over those from another. At Ranginui, I can spend a hectic morning indoors, slave to telephone, fax and email, and then, in 10 minutes outside checking the hens’ water, shifting sheep from one paddock to another or feeding out a bale of hay, I literally feel the mental fog blowing away.

As Andy Barratt says, “Beyond any doubt, developing our property’s been the most rewarding thing we’ve ever done.” And Sue Barratt speaks for many smallholders when she adds: “Every weekend is like going on holiday!”