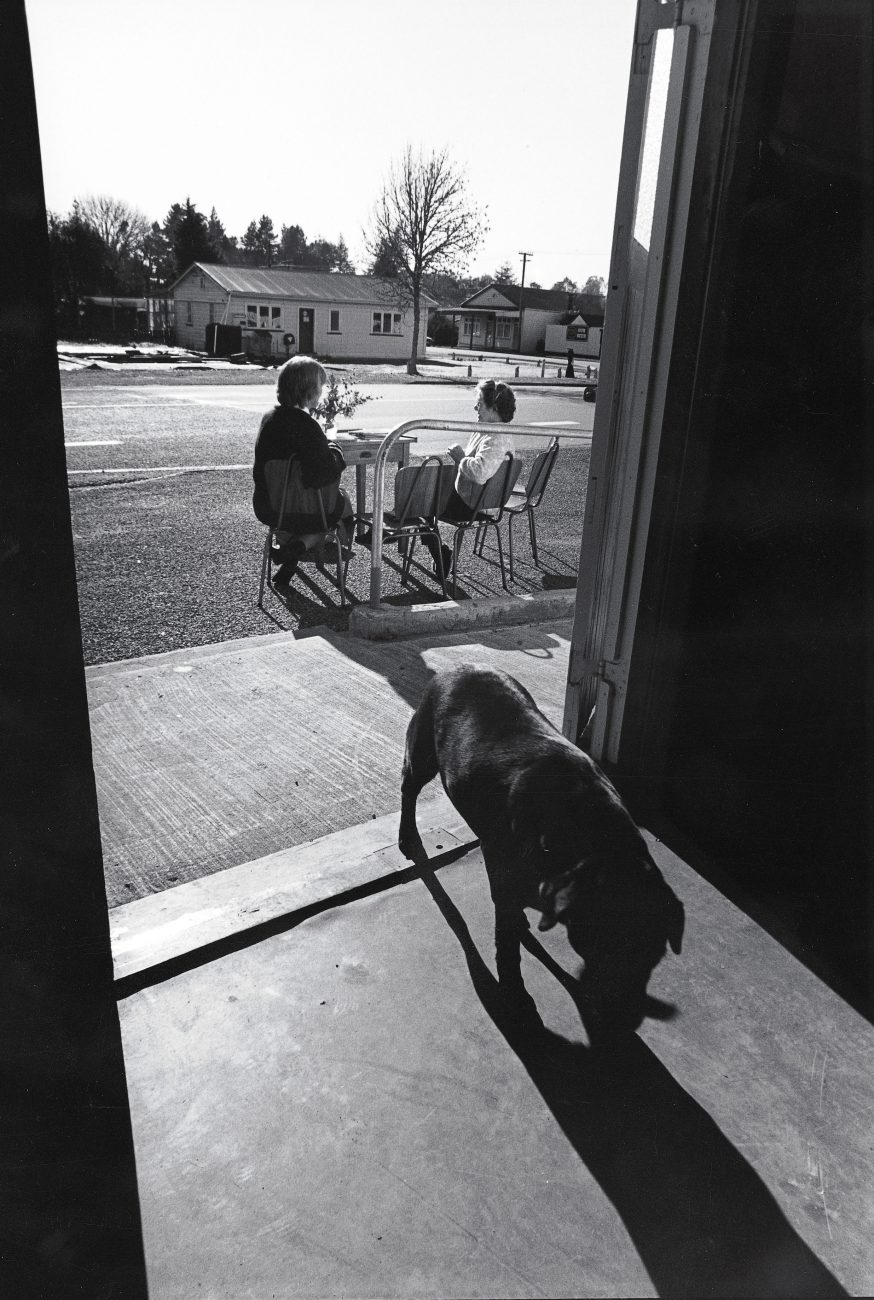

Country doctor calling

David Burrell—affectionately known as Dr Buzz—is a partner in the two-doctor practice that brings medical care to the people of Reefton and the surrounding area of the West Coast. The Coast may be a stunning place to live and raise a family, but the benefits of country living barely compensate for the crushing workload Buzz Burrell—and other rural GPs—have to cope with.

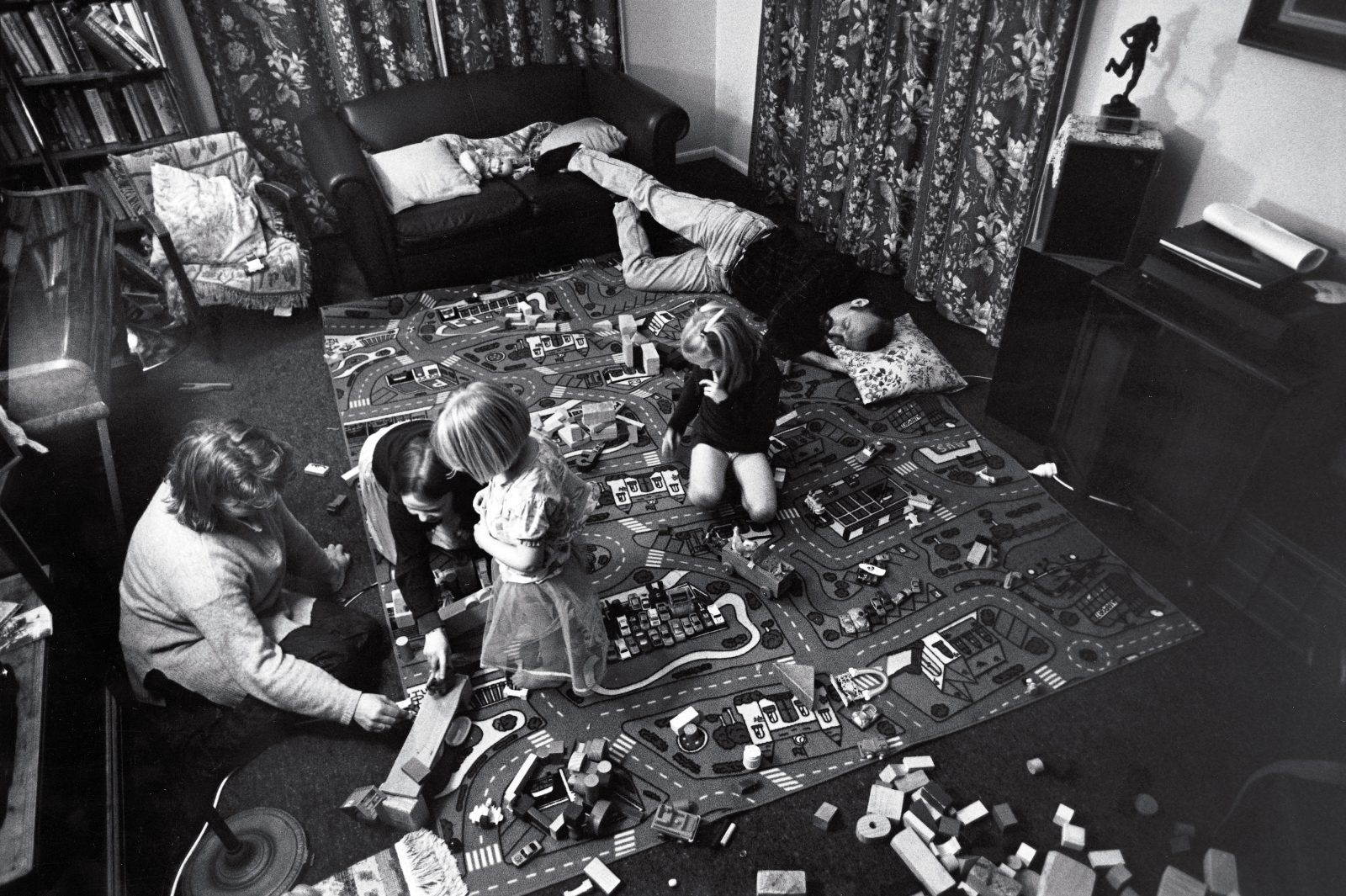

Daisy has an “R”-day at school. She has already found a rope, a ring and a ribbon. Lily needs “something round” for her class. Poppy, the youngest of the three girls, is a bit sad this morning. Dr Buzz is carrying her on one arm while he brings some raisins and a rag for Daisy.

“We are not late, we just lost our advantage!” he yells, stoking the coffee plunger. His wife, Lauren, is getting ready for a trip to Greymouth, 80 kilometres away, where she is to give a presentation as part of her studies for a nursing degree. Buzz is organising breakfast.

He is also on call. A pager is clipped to the towel he flung around himself after a quick shower. This little gadget may sit there quietly, but its very presence makes Buzz and Lauren tense. If someone between Reefton, Lewis Pass, Inangahua and Ahaura—an area twice the size of Greater Auckland—needs a doctor urgently, the pager will go off. Dr Buzz will jump into a pile of neatly arranged clothes and out the door. Lauren will have to rearrange her travel plans.

[Chapter Break]

Since 1993, Dr David “Buzz” Burrell and his associate, Dr Julian Ashburner, have provided medical service to the people in Reefton, a small coalmining and timber town lying inland between Greymouth and Westport. They service the surrounding area, too, looking after a total of about 3000 patients.

Like many rural GPs in New Zealand, Julian and Buzz are expats—both came here from England. However, they have not used country service as a mere stepping stone to an urban practice where they could earn more than twice as much. They came to Reefton because they wanted to. They wanted to be part of a caring community, and they wanted to be their own bosses.

Like many small towns, Reefton has seen an endless succession of locum doctors. When Buzz and Julian bought homes in Reefton, the locals breathed a sigh of relief: stability had returned to an important part of their lives. The new doctors even started planting pine trees in the area. “It’s our pension scheme,” jokes Buzz. “I will be a rich man, when I’m 110!”

[Chapter Break]

Dr Buzz makes his way to the surgery, which is located in tiny Reefton Hospital. He arranges the chairs in an inviting array, props the window open with a tuning fork which happens to fit in the hole under the frame, and waters the plant above the bed.

“People lying here don’t want to look at something dead,” he says.

Before the day’s patients start to arrive, Buzz visits others across the hall in the hospital. One of them, a former wood-chopping champion, is old and can barely walk. He is depressed and wants to go home. Buzz examines him, but for most of the time he just holds the man’s hand and talks. This doctor not only prescribes medicine, to his patients he is medicine.

He checks a newborn baby and her young mother. Both need rest. They do not yet know if the baby’s father is interested in them.

At the other end of the building the waiting room is filling up. The first patient volunteers to make a cup of coffee for Dr Buzz, who is studying her file. He takes a throat swab to test for strep bacteria. He knows how to break the bad news: “This test is so positive it will soon start melting the table!”

The chest infection of an elderly man has cleared up quickly. He is in good spirits and very thankful to the doctor. “Don’t thank me, I just supplied the petrol—you did the driving,” Buzz tells him.

He speaks the language of his people. He clears up the confusion of another patient regarding the actions of two types of pills to get high blood pressure under control: “These ones are the V8 under your bonnet and these ones are the fluffy dice.”

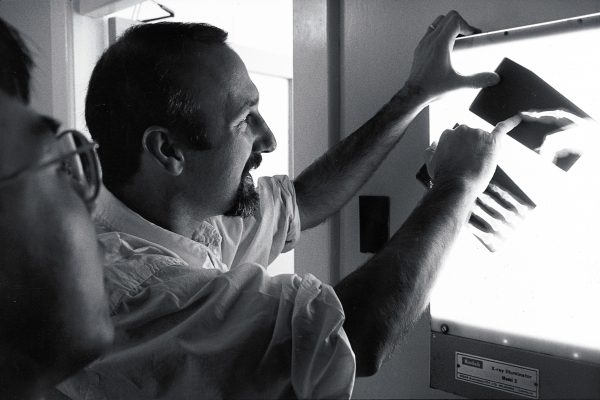

The steady flow of patients is interrupted by an emergency. Buzz rushes over to the hospital. A woman passenger on the Hokitika bus has collapsed. She looks pale and frightened.

Dr Buzz runs some tests and organises an ambulance to Greymouth Hospital, which is closer to her home. The woman does not know who her local GP is—the old one left a few weeks ago.

Back in the surgery Buzz examines a miner who has a cut in his forearm. It is so deep that the tendons are exposed. Buzz spends a long time cleaning coal dust off the wound. A nurse shines a torch into the gap. After an hour, the miner leaves all stitched up. Like most patients in Reefton, he does not need to pay.

[Chapter Break]

When the two doctors took over the Reefton practice, they slashed charges. Consultation fees, structured according to age and income, range from zero (for the majority of patients) to $28. Return visits are either half the cost of the first visit or free. On top of that, many patients leave the surgery with free medication from the sales-rep stash.

“I’d rather have people spending money on their children.” Buzz says. “We are motivated by Christian and socialist beliefs and try to provide quality community healthcare—not the market model promoted by the National government’s reforms.”

The doctors dream of a completely free primary healthcare system for Reefton along the lines of one which operates successfully in Hokianga. There, the community elects a board of trustees who decide what they want from their health service and appoint an executive officer who runs the operation. Doctors are paid salaries and are based in the small Rawene Hospital, visiting nine outlying clinics once or twice a week. Community nurses staff the clinics full time. The small hospital has a few beds for acute, maternity and long-stay patients. Mental, dental and home-support services are also provided to the district’s 9600 residents. Doctors’ visits and drugs are free. Even allowing for services provided to residents by medical facilities outside the area (for example, by larger hospitals in Whangarei or Kaitaia), Hokianga healthcare costs the Health Funding Authority less than two-thirds the national per-patient average.

In Reefton, Buzz and Julian have calculated that a saving of just seven per cent on their current budget would allow them to stop charging patients altogether. And more than that is wasted in the current system on paperwork and bureaucracy alone. A combined hospital and surgery owned and run by a community trust would easily achieve the savings, and allow people in the economically depressed West Coast town free access to healthcare.

[Chapter Break]

The healthcare improvements extend beyond Reefton. Buzz and Julian have also established weekly clinics in the community halls of Ahaura and Ikamatua, at the backpackers’ hostel in Springs Junction and in the school staffroom at Inangahua Junction.

It takes about 20 minutes to drive to Ikamatua. The rolling hills make for a scenic drive, but for Buzz they are also the reminder of medical emergencies of the past. He knows the story behind each white cross alongside the highway. “This corner does not have a cross yet, but we attend a crash at this particular spot about once a year,” he says.

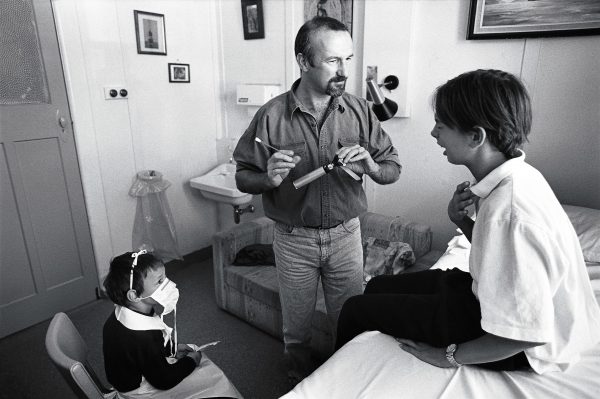

In Ikamatua a patient helps unload the truck. Carol, the nurse, climbs up to the fuse box, and the lights and heaters in the community hall come on. She sets up office and surgery in the bar. Buzz works in a room which is also used as a playcentre.

The first patient sits next to him while he tries to bring order to a huge stack of test results. “Don’t go away, I’m nearly there . . . Now that I have cured your files, what can I do for you?” The woman needs a check on her blood pressure.

A farmer needs a splinter removed from his foot. After two months, it has become infected. An embarrassed teenager needs some advice on contraception. Dr Buzz pulls out a photograph of his three girls and explains the circumstances in which each one was conceived. This puts the young woman at ease.

As the day wears on, long past official surgery hours, Buzz tries not to lose his concentration or humour: “This may be the 30th patient I’ve seen today, but I am the first doctor he has seen, maybe for months. I want to communicate that he is important.” He does not overestimate his own importance, though, and holds with Voltaire, according to whom “good doctors keep their patients amused until they heal themselves.”

[Chapter Break]

When Buzz arrives home it is dark. Conscious that busy family doctors can all too easily neglect their own families, he reads a story to Poppy and Daisy. At eight o’clock the family sits around the table and starts dinner with a prayer. The children are encouraged to talk about their day. Lauren thinks her presentation went all right.

Buzz is still on call, and so, indirectly, is Lauren. She will have to stay home with the children in case Buzz needs to go out.

The constant disruptions of the pager to meals, sleep and normal routine wear down many rural doctors. Taking any sort of holiday or break poses real problems. If Julian has a week off, Buzz is exhausted by the end of it, and he then needs a week’s rest to recover, and so on.

Locums are almost impossible to obtain, especially when they hear about the amount of on-call work. Even if they can be found, they demand fees so high that it takes the low-budget practice months to recover financially. Maintaining accreditation with the Royal College of GPs means regularly attending refresher and update courses, but this leads to the locum problem again.

Trapped and burned out, many rural GPs throw in the towel, swapping the country for more lucrative urban practices with regular hours and little on-call work.

Various organisations are trying to make rural practice more survivable, but the number of doctors willing to work longterm in remote areas is still declining.

[Chapter Break]

At nine o’clock the phone rings and Buzz hurries out to visit a child with suspected pneumonia. He is back half an hour later and starts surfing Medline on his computer to find the latest research for a woman with a rare condition.

At 10.30 he rushes to the hospital. A boy sits pale and wide-eyed in the disused operating theatre. He can hardly breathe. Buzz administers nebulised adrenaline with oxygen to relieve the symptoms of acute epiglottitis. An ambulance is organised to drive the sick child to the hospital in Greymouth. His mother goes with him, and Buzz drives her Holden back to the house and hides the key under the mat so her husband can go to work in the morning.

Buzz goes to bed at midnight. He is tired and a little tense. Who knows, tonight there could be a major accident on Lewis Pass? He is the only available doctor within a radius of 150 kilometres. He hopes he is prepared.