Edge city

Like a runway to the future, Auckland’s northern motorway slices across oxidation ponds to reach Albany—a long-neglected rural backwater which is being abruptly transformed into a new city. Despite the speed of change, the district has refused to let its identity be quashed by the encroaching metropolis, and Albany in 1998 presents itself as a colourful mixture of country tenacity and urban flamboyance.

The term “Edge City” coined in 1991, describes the phenomenon of major commercial and retail centres forming on the outskirts of existing cities—and it fits Albany to a T. Sometime in the last decade, Albany let go its rural status and rocketed into orbit as a satellite circling Auckland’s sun. The once quiet basin now wakes each morning to the sounds of earthmoving machines, concrete mixers, nail guns and that universal indicator of progress: traffic.

Where orchards once stood, swanky subdivisions and sprawling industrial estates have taken root. Architects, quantity surveyors and town planners shuttle from one bulldozed patch of ground to the next, supervising the development of “new Albany,” a city in the making.

Since 1991, Albany’s population has grown from 9000 to 14,000. The town now boasts the country’s smartest sports stadium, a university campus, one of Auckland’s most prestigious private schools and a burgeoning commercial centre—and the urbanisation programme has only just begun.

Standing on the uneven clay after the turning of the first sod for Australasia’s biggest supermarket (it will cover an area the size of two football fields), Gordon Davies, property manager of Foodstuffs, estimates $100 million will be invested in the development of the new city in 1998 alone.

“This is the beginning of what must be the most exciting project in New Zealand,” says Davies, whose Pak’N Save will, in August 1998, join superstores already established on a 126-hectare city centre planned for Albany.

“I have immense confidence in the future of Albany,” he says. “Absolutely.”

Though only a short motorway drive from Auckland, Albany was neglected in the rush to settle near the golden beaches of the North Shore’s East Coast Bays, Takapuna and Devonport after the harbour bridge opened in 1959.

Lacking “destination appeal,” as marketers put it, Albany was a place people passed through on their way north, but where few cared to reside. Just why the area took so long to develop is something of a mystery. Head south from central Auckland and it is a long time before you will find anything approaching empty space. Yet here was a vast area only 15 minutes from central Auckland largely devoid of human life.

Albany became hot property only after the North Shore City Council unveiled an integrated 20-year plan and the New Zealand Housing Corporation sold 350-hectare to private enterprise in 1993—a grand scheme that had undergone a 30-year gestation.

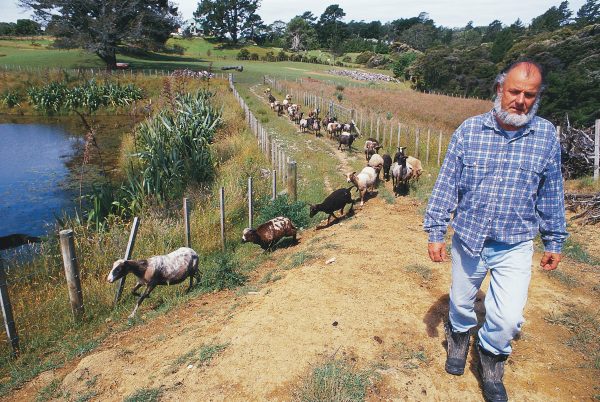

Handed such a windfall, you would think Albany’s landowners would be feeling rather pleased with themselves these days, busily farming capital gains instead of livestock or vegetables.

But many would sooner have preserved their livelihoods and lifestyle than reap overnight riches, and have been reluctant sellers, driven off their holdings by the changes happening around them.

Retired cartage contractor Robert Stevenson, a descendant of a 19th-century gumstore owner and Albany’s postmaster, looks towards the new regional centre site and remembers his father’s wrath when he was forced to sell that parcel of land cheaply to the government, under the iron fist of the Public Works Act, in 1960. Even then, both central and local government foresaw that the 2500-hectare Albany basin could become a major part of expanding Auckland and acquired some 700 hectares to ensure they had control over the development of the region. In the event, Roly Stevenson’s land lay unused for 30 years after the collapse of a state housing scheme, to be sold to developers only in the last few years.

The history of the Stevensons and Albany is one and the same. Mention of the new university campus prompts a story of how Robert’s grandmother, Electra Phillips, buried the family chandelier where the university now stands. It seems she was annoyed at family members angling to own it after her death, and hid it to halt the arguments. The chandelier, with its crystal droplets, was never found.

Every month, Robert Stevenson attends a meeting dedicated to preserving the history of the settlement that started as a supply post for timber men (in the 1840s) and gumdiggers (after 1860). He interviews elderly residents and collects photographs of the old days to ensure that the new Albany has some heritage to look back on. “The district’s changes will be so immense, we’re in danger of losing what we’ve got,” he says.

In Stevenson’s childhood, Albany was a dreamy meadow, a paradise for children, a place to play with birds and frogs; a place where you could eat your fill of fallen fruit and wash it down with cool water from the village handpump on the way home from school.

“Up until the 1960s, we knew everyone in Albany. Not any more. Now we can’t wait for the motorway to bypass it so we can have some peace again,” he sighs.

At the time that his great-grandfather William Stevenson, an Irishman from County Antrim, arrived at the township in 1856, Aucklanders lived with the smell of smoke from bush and scrub fires burning at Albany (then named Lucas Creek, a corruption of the name of the first European settler, flax trader Daniel Clucas), as gumdiggers foraged for golden nuggets following the removal of the great kauri forests.

The diggers were men of varied backgrounds—among them remittance men, criminals, runaway sailors—whose labours supplied gum for the varnish trade. Liquor smugglers in turn supplied the diggers with refreshment, and the area acquired a pretty rowdy reputation.

In the 1880s, as the gum started to run out, fruit growing started at nearby Greenhithe and quickly extended into the Albany basin. Not only was Auckland supplied, but fruit was soon exported to Australia and further afield. By the 1890s, 30,000 to 50,000 cases of apples and pears were being produced each year.

A public meeting in 1890 renamed the settlement Albany in an attempt to alter the district’s unwholesome image. The new name was that of an Australian fruit-growing district, pronounced with a short “a” as in Albert. The name achieved prominence in the form of two particularly productive strains of fruit later discovered in and named for the area. One was a black, disease-resistant grape, a sport of Isabella, which became famous as Albany Surprise, and the second was the Albany Beauty sport, discovered on a Gravenstein apple tree where the Massey University campus stands today.

The orchards are all but gone. Aucklanders no longer flock here for apples, peaches, pears, nectarines and strawberries as they did after the Auckland Harbour Bridge was opened. Today they are more likely to be visiting the industrial parks or the North Harbour Stadium, home of North Harbour Rugby.

[Chapter Break]

Commercial developer and investor Allan J. Wiltshire is driving me around the North Harbour industrial estate in his leather-lined Range Rover. There’s a look of confidence about these wide streets and smart new buildings, and Wiltshire seems to have a story to tell about every one of them.

The area has been promoted as New Zealand’s Silicon Valley. Big-name tenants such as Sony, Sanyo, PC Direct, Hasbro, and Mattel have legitimised the notion.

“Demand for space has been strong,” says Wiltshire. “A few years ago, if you were lucky, you could have picked up vacant land for $37 per square metre, but today it’s more likely that you’d pay $165, like the fire service did for its new station.”

Medium-sized ma and pa companies come here when they outgrow their premises elsewhere in Auckland, says Wiltshire, pointing to a typical example. “We put up that new building for a little factory from Wairau Valley. It was 700 square metres, and immediately the company had a new lease of life. Now they want an extra 400 square metres.”

After spending nearly a decade doing daily battle against the traffic from their Greenhithe home to Auckland’s trendy Parnell district, importers of children’s novelty items Roger and Arlene Tyler decided to relocate their office to Albany. Now they live six minutes’ drive from their 1000-square-metre warehouse. Business is booming, they say. Demand for their Disney, Barbie and Skydancer accessories has led them to double their staff to 16 in two years. The Tylers’ Artco showroom is on a circuit well worn by buyers who stock up from five publishers and toy manufacturers now based in Albany.

The trickle northward is predicted to become a torrent. A foreman I spoke to at a North Harbour industrial building site told me forcefully that Albany as a separate entity is a thing of the past: “It’s all North Shore now. The new city centre here will make Takapuna look like a corner dairy.”

Being on the ground floor of a grand design has its drawbacks though. Locals complain that the traffic, particularly from the end of the current motorway into Albany village, is a nightmare—one destined to continue at least until the northern motorway extension from Albany to Puhoi is opened early next century.

Albany’s shopping village at the historical centre of town desperately needs relief in the form of a local shoppers’ road to relieve the pressure of bat-ding highway traffic, says Albany Business Association president Amber Lomas. A fruit seller in the old part of town, she fought the council for five years to get a road installed—before land prices went skyward.

It’s as though old Albany is so unimportant that it doesn’t exist. The council is not interested in what’s already here, only in the new centre. I’m not saying the development of the area is a bad thing, it’s just that we, the ones who are here now, end up being fobbed off. I think it’s fair to say that until the traffic problems are sorted out, the existing businesses will not prosper.”

The inevitability of change has set the cat among the roosters as Albany village retailers struggle to keep existing customers. They worry that their biggest drawcard, an aging Three Guys supermarket, will up-stakes when the new retail centre a kilometre closer to Auckland gains momentum.

The area’s businesses believe the village’s survival will depend on its being seen as a semirural Parnell or Devonport, with speciality boutiques, professional services and the village’s trademark 100-strong flock of free-roaming poultry adding a quirky rustic charm.

Another attraction is Albany’s small gem of a park, which includes the remains of an old orchard. Down the lower slopes, families picnic beside Lucas Creek. Keep walking beyond the totara grove, along the sluggish river, and you can walk underneath State Highway 1 and strike off on a steep bush walk, leaving the traffic buzz far below.

[Chapter Break]

It was during the 1970s, when infill housing started to splinter the quarter-acre section and suburban privacy became just a memory, that refugees from city and suburb started to seek out the countryside, including the environs of Albany. Many of these escapees settled on 10-acre blocks, as often as not a mixture of bush and pasture on rolling or steep ground. Zoning rules generally inhibited the subdivision of the more productive rural land which the orchards occupied.

These small blocks were large enough to feed a couple of dozen sheep or a handful of cattle, but ponies were a favourite with the girls—and not just country kids. Plenty of city girls owned a horse and leased grazing in Albany. Pony clubs were big, as were ribbon days, one-day events and gymkhanas. Little troupes of horses and their slightly apprehensive black-helmeted riders regularly clip-clopped along the verges of local roads, even the main highway.

Lorraine Patten of the North Shore branch of Riding for the Disabled estimates that there were as many as 800 horses around Albany. Even after the Housing Corporation’s land was sold in 1993, the Albany Pony Club leased land from the developer, but now that land has gone under the bulldozer blade. The club has been forced to lease paddocks in Stillwater, 15 kilometres away.

Club members say that the polite but emphatic message from council and developers has been that the horse is no longer appropriate in Albany. Disenfranchised riders cast baleful glances towards the industrial blocks and sports centre. At a meeting of pony clubs, someone made the comment that if horse riding was a male-oriented sport, as rugby is, there would be no problem with grounds.

The replacement of Albany’s rural swathes and orchards by roads and buildings has been the most dramatic change to Albany’s landscape over the last several years. Before World War II, there were 56 orchards in the district, most of them long established.

Leo Floyd, a fruit-grower, comments: “A few years ago, council put up our rates 400 per cent in one year. Then along came the bulldozers, trucks, speeding traffic and industrial buildings popping up all over the place. It scared off the people who used to come here to buy our fruit, and now it’s no longer economic to stay here. We are moving out of Albany, my home town, to continue fruit-growing at Riverhead.” Floyd’s orchard, now zoned industrial land, is in full, poignant bloom as he and his family prepare to leave it behind.

Former Albany orchardist Sid Clemow’s 14-month unsuccessful battle to save his patch of dirt ended with his admission to a coronary-care unit. In 1974, when government already had 700 hectares of Albany land, it decided it required a further 200 hectares “to ensure the orderly development of the basin as a new urban community,” as the office of the Minister of Works and Development wrote to those whose land was about to be acquired.

Locals were outraged by the threat to their livelihoods and fought the government with petitions and legal action. The ministry finally backed off amid a hailstorm of criticism, and the orchards secured a 20-year reprieve—but ultimately, the men of the land lost the war.

Now, with the last of the orchard established by his father in 1912 sold to developers, Sid Clemow has joined the new Albany. Remarried at 70, living in a Universal Homes brick-and-tile subdivision, Brookfield Park, a kilometre from his old orchard, he tends his flower garden, something he never had time for during his fruit-growing days.

“I haven’t planted any apple trees in my new garden,” he says. “I’ve had enough of that. We thought we had won, but we lost in the end.”

New Zealand Herald cartoonist Minhinnick’s “approaching swarm” cartoon, depicting an angry orchardist spraying a cloud of developers, politicians and planners, was still fresh in the public’s mind when the then Takapuna Council slipped quietly into the driver’s seat.

Former North Shore City planning director David Hughes’ clipped southern Welsh voice intones unemotionally how the government ran out of steam after the orchardists kicked up in the 1970s. Major earthworks at an Albany university site were abandoned first, followed by government plans to use the basin for state housing.

During the 1970s and 1980s, the council strengthened its bonds with Albany’s largest landowner, then the Housing Corporation. The corporation liaised with city planners to identify future zones and gradually develop a package of land uses and recreation areas, while protecting aspects of Albany’s environment.

Although Albany is destined to become almost entirely urban, the council’s greenfields zones assure future citizens of a wide range of recreational facilities: parks and bush reserves, rugby, soccer, hockey, softball, and cricket fields, tennis courts, a golf course and a $30-million water theme park.

[Chapter Break]

Graeme Platt is a thorn in the side of the interlocking teams of planners. He regards the urban dream as a nightmare. An afternoon with him and his Australian wife, Rosemary, is like being at the vortex of a political whirlpool. Bearded and intense, Platt speaks rapidly, swooping on any intimation that North Shore City may have done the right thing by organising orderly development at Albany.

“We’re being swamped by suburbia, robbed of the source of our own identity by a tide of bureaucracy!” he explodes. “The council’s sole aim is land subdivision. It has taken charge completely. The council members talk about consultation, but public meetings aren’t consultation. We go to these meetings and we are unrealistic—bearing in mind they want to house half of Saigon and Bangkok here. The European population isn’t expanding at all.

“Democracy is government of the people by the people. We have got government by the bureaucrats for the perpetuation of the bureaucracy. The new Albany was conceived in the bowels of bureaucracy, not from the heart of Albany.”

Platt and his equally articulate wife are fighting a fistful of battles, in varying stages of preparation: North Shore City Council v Platt; Platt v NSCC; Platt v the former Lands and Survey Department.

The Platts operated New Zealand’s first dedicated native plant nursery on Albany’s main road from 1974 to 1995, but the site has recently been leased by an oil company for a petrol station. Beside his attractive new house, Platt now maintains an experimental kauri plantation, testing his idea that kauri grows best as a swamp plant.

Unlikely as it may seem to harassed council staff, who fmd his warrior spirit daunting, for a number of years Platt suffered from chronic fatigue syndrome, or ME, a disorder which he claims to have overcome by taking regular doses of a cocktail of 26 minerals “essential for bodily functioning.” He is certain that local soils are deficient in many of these minerals, and considers that ME represents an “enraged immune system ravaging the body’s own mineral-deficient proteins.”

Although supplying the widespread demand for this elixir makes some inroads on his time, plants remain dear to Platt’s heart. He can’t resist trotting out one of his digs, to raise the hackles of flower-lovers everywhere: “You see gardeners every weekend, their noses in plants’ genitalia. I don’t know why people concentrate so much on flowers; the whole plant has so much more integrity . . .”

If, as Platt says, “mother’s cultural indoctrination” towards roses, petunias and camellias was to blame for the wholesale ripping out of natives be fore native plant consciousness took hold sometime in the 1970’s, no one would dream of mentioning the idea at the 67th birthday party of the Albany Country Women’s Institute, where floral sprays are carefully pinned on the lapels of members from visiting institutes.

President Peg Welsford asks for a few moments’ silence to reflect on “all the dreadful tragedies and all who are troubled, including the Queen and her family.”

It is mostly visitors who swell the numbers inside the stoutly built George VI Coronation Hall. Once secure on Albany Horticultural Society land, the kauri hall is now stranded on a triangular island, where the noontime traffic hum competes with encroaching bulldozers.

A member passes on an apology for an absent friend whose husband has just had a bypass operation. Her comment: “He is home, but, manlike, will do too much if not watched with a close eye.” After candles representing Albany CWI’s past, present and future are ceremonially fanned out on a cake made and iced by member Lillian Smith, raffle winners are announced.

The proceedings seem timeless, a manifestation of an ancient Albany of apple trees and three-digit telephone numbers in which the main business was the country pub; an Albany that existed long before the district ever made headlines.

Perhaps Albany first entered national consciousness through the activities of Centrepoint Community, started by pest eradication specialist turned spiritual leader Bert Potter 20 years ago.

Conceived in the afterglow of the hippie era, Centrepoint offered “radical freedom and deep intimacy,” and encouraged its members to get rid of their own hang-ups (which to Bert often included monogamy) and work through their conflicts with others. Members pooled their money to buy land, and in 1977 the Centrepoint Community Growth Trust was formed, with Potter as its first spiritual leader.

“Centrepoint is based on peace, love and the discovery of our human values,” wrote Potter in 1993, but since 1995, issues of power and money have regularly brought the trust before Auckland’s High Court.

The conviction in the late 1980s of a handful of members, including Potter, on child sex and drug charges has left only a small core of about three dozen members out of 280 who formerly lived on the property. Unresolved questions about the Centrepoint trust’s charitable status and ownership of its estimated $12 million in property, plus financial claims from disgruntled former members, promise plenty more work for the legal profession.

The cornerstone of contention is the Centrepoint Community Growth Trust’s clause which says members must forfeit all their worldly goods to the trust, which guarantees to provide for all their needs. Among various legal actions in progress is a $100 million suit against the Attorney General for failure to protect the trust and a challenge to his appointment of the Public Trust Office as interim financial overseer and preparer of new trust and community deeds.

Due to be released in 1999, Potter has never been replaced as the spiritual leader in Centrepoint’s charitable trust deed. Most Centrepoint observers believe he still holds the commune’s key power cards from his cell in Auckland Prison at Paremoremo, just a few kilometres away from where he once held sway over New Zealand’s most famous extended family.

Today’s Centrepoint has a subdued feel to it. The cushions around the walls are faded, the air musty in the once-famed Red and Green Rooms, where group sexual therapy took place. Centrepointers still drive to Albany village to collect supplies in their numbered diesel-fuelled fleet cars. Their presence does not challenge the locals as it once did, when a third of Albany’s school roll was from Centrepoint, and non-Centrepoint parents became embarrassed by affection publicly displayed, and finally alarmed by rumours that sex was not confined to consenting adults.

In the face of the new tidal wave of development, Centrepoint has almost become part of the old Albany establishment, and, like it, in danger of being overwhelmed. Its splendid 31.5-hectare reforested valley is much envied by developers but considered too legally entangled to contemplate buying at present. Beside its entrance a 32-court tennis complex (five indoor) is planned, together with a 1000-space car park.

[Chapter Break]

If centre point once kept the nation’s attention fixed on Albany, Allan Clarke was the man who, more than anyone, put the town on the commercial map. The softly-spoken car dealer started modestly in the village in December 1974, selling used cars, but his business rapidly expanded to become a major outlet for new and used Japanese, European and Australian vehicles.

His catch phrase “only 12 minutes north of the bridge” was beamed from radio stations all over the Auckland province, and during his heyday, from 1983 to 1990, he was turning over in excess of $100 million per year. Sales in the best month totalled 755, he says, trotting out the figures as though it were just yesterday.

Clarke’s year-in, year-out publicity campaign and ever-expanding premises caused locals to refer jokingly to their town as Clarkesville. Clarke himself says that efficient service was the key to his success: “We could do a complete service on a Corolla—including not just all the usual things but a wheel alignment, engine steam clean, vacuum, outside wash and polish and blackening the tyres in 35 minutes—while the customer worked out in our gym or watched a video.

“Twice a year we held huge car sales and got in Brendan Dugan and his band to create a shindig. Mery Smith would announce from the forecourt that for the next two hours petrol would be only 50 cents a litre. That would cost us $5000 a hour, but it would bring in so many people that there would be traffic jams covering half the Shore.”

A finance company put the whole empire into receivership on ill-defined grounds at the start of the 1990s. Even so, Clarke, now a forestry entrepreneur, somehow cast the die for Albany, as the village remains dominated by a constellation of lesser caryards—seven at last count.

Around the same era as Clarke, maverick bulk-meat merchant Earle Thompson also brought the name Albany into the public eye. Starting with one discount Albany Meats shop on the main road, he pioneered Saturday trading. Four additional stores were later established around the city.

Thompson became deputy leader of Bob Jones’ New Zealand Party and its Rodney candidate in the 1984 election.

Another major but more recent player in Albany’s ascent, Massey University purchased 73 verdant hectares from the Housing Corporation in 1989 and today provides degree courses for 3500 students on the Albany campus, in addition to 8000 at its main campus in Palmerston North and 17,000 extramural students.

In the mid-1970s, the then University Grants Committee had commissioned earthworks for a new northern university at Albany, but the move caused a commotion in the academic world, which argued that a young Waikato University needed all possible resources. Albany was promptly axed.

However, in light of Roger Douglas’s user-pays philosophy and the UK Jarrett report on universities, former Massey vice-chancellor Neil Waters realised that universities would soon feel the pinch if they did not move with the times. With 60 per cent of Massey’s Palmerston North students coming from outside Manawatu, especially from Auckland, predictions of a new academic climate had major implications for Massey.

“You could see there was going to be a lot less support for students, and that meant it would become more difficult for students to move from their home towns,” comments present Albany campus principal Ian Watson.

“We perceived the threat before other universities did, and thought that if Auckland University wasn’t going to Albany, why shouldn’t we go? We decided to take the mountain to Mohammed.”

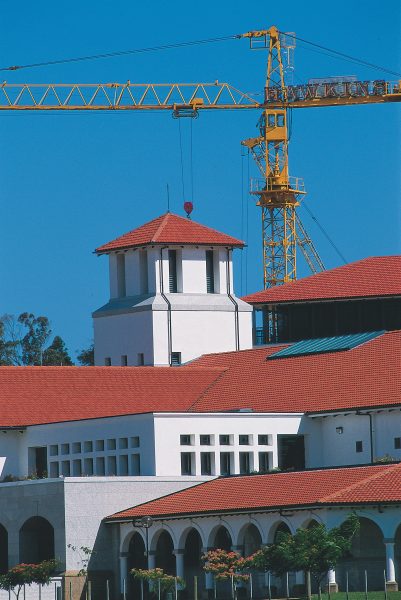

The exercise of establishing a Massey satellite campus at Albany began in 1993, when it opened with 500 students. It seemed curious for a university to be housed in several dozen kitset homes (erected in mere months), soon presided over by an imposing Mediterranean-style building the best part of a kilometre distant, but it made good commercial sense to set things up gradually.

The Albany campus is growing by about 500 students per year, and offers courses in business, science, education, humanities and social science. Links between “town and gown” are strengthened as academics study their new backyard. Led by professor Paul Spoonley, a team of sociologists explores North Shore issues—most immediately, transport and environmental concerns—brought about by the rapid growth in the area. Business studies students regularly invite the township’s business people to “network” at breakfast seminars.

Across the road from the university lies the futuristic North Harbour Stadium, part of the North Shore Domain, a new sports and recreation complex. I watch as stadium general manager Graeme Running tries to sell seat packages to a group of sightseers: “It’s the first curved stand in the country, with a perfect view from wherever, and these are the best lights ever seen in this country—by a country mile. We are creating a social and networking environment second to none.”

From the main lounge, with seating for 1400, visitors look out over the clay landscape where Albany’s regional centre will be established in the new millennium. A brand new roading system is dominated by the circular Don McKinnon Drive, named for the former deputy Prime Minister, who represented the area from 1978 and remains a regular dignitary at countless official openings on the industrial estates back down the highway.

The 126-hectare regional centre site was bought in 1994 for $21 million by site developer Neil International. Neil’s managing director, Dick White, says the project is a special opportunity and challenge because it involves a large block of land where integrated overall planning has been possible—in marked contrast to the piecemeal and add-on planning that has marked much of Auckland’s progress for over 30 years.

[Chapter Break]

In the 19605 and ’70s, it seemed that Albany was the ugly sister of the North Shore, getting all the dirty jobs: the oxidation ponds, the maximum security prison, the crematorium and cemetery, later the refuse tip.

Now, with an impressive stadium, university campus, expensive private schools (such as Kristin), housing estates and a grand shopping centre to come, the town is becoming the belle of the ball.

One who would have been amused by the turnaround is poet A. R. D. Fairburn, whose grave lies only a few hundred metres from all the cranes and new concrete. According to his late younger brother, Thayer, Fairburn was interred at Albany in 1957 because it was the cheapest place to bury him.

His grave in the small country graveyard went unmarked for seven years, until several of his friends chipped in to erect a 350-kilogram basalt stone.

Thayer Fairburn is not sure that Rex would have approved of a tombstone, but he feels his brother would have liked the Albany cemetery of the 1950s, set in the heart of a quiet and pleasant district.

Fairburn’s brief but telling social analysis, “The Power and The Glory,” leaves the reader in no doubt of how he viewed the human condition, at Albany or anywhere else.

The road to the abode of the blest has for stones the broken bones of the best.

The worst get there first and their nest is feathered with the feathers of the rest.

The question is: will Fairburn rest as comfortably in the new Albany?