LOADING

![]()

![]()

Meyer Islands, Kermadecs

The last roost

While birdlife on Raoul Island was ravaged by rats and cats from the 1920s, neighbourly Meyer Islets remained free of pests.

Kermadec petrels wheel high above the cliffs at the Meyers, with the dark form of Raoul in the background. Since a massive operation to remove pests from Raoul in 2002, seabird numbers have blossomed there, slowly returning the islands to former glory.

LOADING

![]()

![]()

North Meyer, Kermadecs

Welcome to Sharkland

Below the waterline, the Kermadec Islands are close to pristine, and brimming with sharks—the ultimate indicator of a healthy ecosystem.

Galapagos sharks are a constant presence, lurking like hungry dogs around every corner. They won’t worry a diver, but do keep smaller predator fish under control, maintaining a healthy balance on the reef.

LOADING

![]()

![]()

Raoul Island, Kermadecs

The epicentre

Raoul Island is massive volcanic cone, with a caldera at its centre and two volcanic lakes. Ironically, at present, Blue Lake appears green and Green Lake is blue.

Green Lake erupted in 2006, tragically killing a DOC worker and raising the level of the lake eight metres.

LOADING

![]()

![]()

Boat Cove, Kermadecs

Strange fruit

The Kermadecs are the only place in New Zealand with water warm enough to support coral. Here, in a sheltered crook of Raoul Island, a massive plate coral and other species cling to the reef. Coral is actually an assembly of smaller animals, zooxanthellae, and algae living together as a colony. In turn it supports a wider community of small fish and—lurking in the background—sharks.

LOADING

![]()

![]()

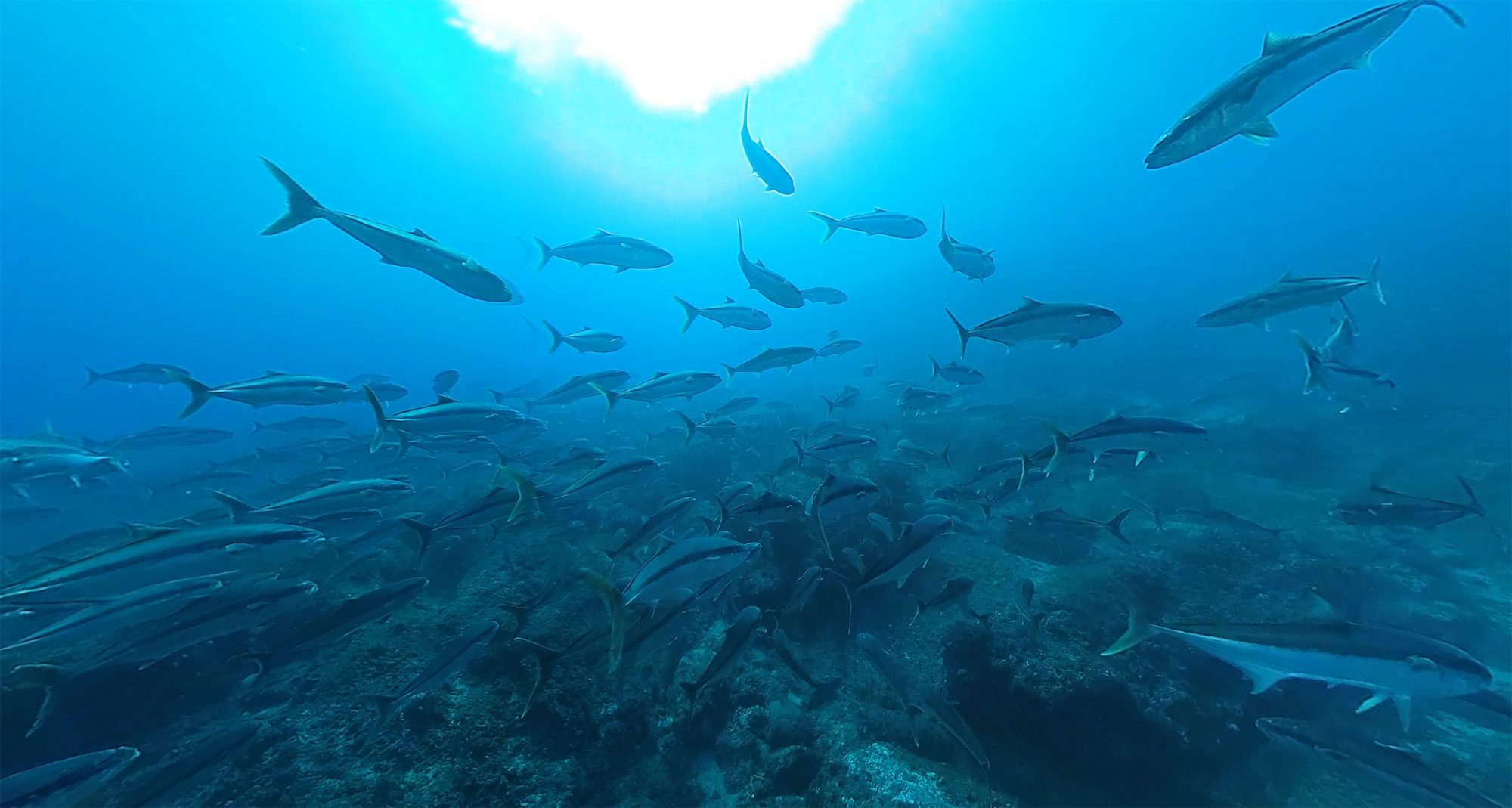

South Meyer, Kermadecs

Scooter with kingis

Director of photography Richie Robinson expertly pilots a dive scooter alongside a school of kingfish, thronging in the shallows at Meyer Islets.

Tropical waters are typically less rich in nutrients than the temperate water around New Zealand, meaning less baitfish are available. As a result the kingis can be more slender, and often turn to eating juvenile petrels.

LOADING

![]()

![]()

Raoul Island, Kermadecs

Ride the mule

Hold on to your hat, you’re riding a mule—four-wheel-drive all-terrain vehicles that can navigate the narrow, bush-cloaked goat tracks that are Raoul’s autobahns.

At nearly 2900 hectares, it’s a large island, and every day DOC rangers criss-cross the rock for surveying, monitoring, weeding, and tending to the island’s infrastructure. There are seven on the island, rotating on 6- or 12-month tours of duty.

LOADING

![]()

![]()

Raoul Island, Kermadecs

The thin green line

After the 2002 predator eradication, Public Enemy #1 on Raoul is no long rats, but weeds—Mysore thorn, black passionfruit, buttercup plant and two species of guava. It can be heavy-going buffalo grass, and even more difficult on the steep cliff faces which harbour Madeira vine. To date, only one species has been totally eradicated, but many weeds have been dramatically reduced in coverage.

In 2017 a menacing pathogen was discovered on the island. Myrtle rust now threatens the island’s endemic pohutukawa forests, creating biosecurity concerns both inbound and outbound.

LOADING

![]()

![]()

Parsons Rock, Kermadec Islands

Foreigners

A small school of boarfish linger in a crack at Parsons Rock off the heaving surfline of Denham Bay.

Tropical fish larvae reach the Kermadecs on ocean currents from the north, but also the south—travelling from Australia’s Great Barrier Reef across the Tasman and past the northern tip of New Zealand. Each year brings new larvae, and fish never seen before at the Kermadecs.

LOADING

![]()

![]()

Boat Cove, Kermadecs

Lions' den

Two lionfish, trailing their elaborate manes with 18 venomous spines, linger in a cave with slender roughy and yellow-banded perch.

Listen carefully, you can hear the echo-location clicks that allow roughy and bigeyes to navigate in the darkness of the cave.

LOADING

![]()

![]()

High Seas

Homeward bound

A good northerly on the quarter makes for easy running home. Point the bow south-west, and follow the Kermadec Ridge for a thousand miles towards the blue horizon. Some days the light will be sharp and the conditions benign, other times the boat will be a rollercoaster careening on the edge of control.

Six hundred nautical miles from the mainland is far enough to protect the Kermadecs from the ravages of most fishing, invasive species and pollution. And it makes the prospect of prospecting less likely too… But it’s not far enough to escape the reach of climate change which threatens to change the chemistry of the ocean itself. Our decisions over the next 10 years will determine the fate of these islands forever.