LOADING

![]()

![]()

Westhaven, Auckland

City on the sea

We are citizens of the sea. Māori arrived in New Zealand by sea, as did Pākehā, and our commercial centre of Auckland lies on the shores of two harbours and at the headwaters of the immense Hauraki Gulf, Tikapa Moana.

We are also guardians of this ocean space, and kaitiaki of all within it. There are places that remain pristine, and places where the mauri has ebbed away in the wake of development. It’s time we considered our role in health of the gulf.

LOADING

![]()

![]()

Viaduct Basin, Auckland

Beneath the boats

Beneath the granite-clad apartments and superyachts, NIWA divers survey the pontoons of the Viaduct Basin.

The Mediterranean fanworm was discovered in Lyttelton in 2008. MPI attempted to eradicate it using divers both there, and in Auckland’s Viaduct Basin, after the fanworm spread. Despite their efforts, it became widespread in the Waitematā by 2010, and eliminating it is no longer considered feasible.

LOADING

![]()

![]()

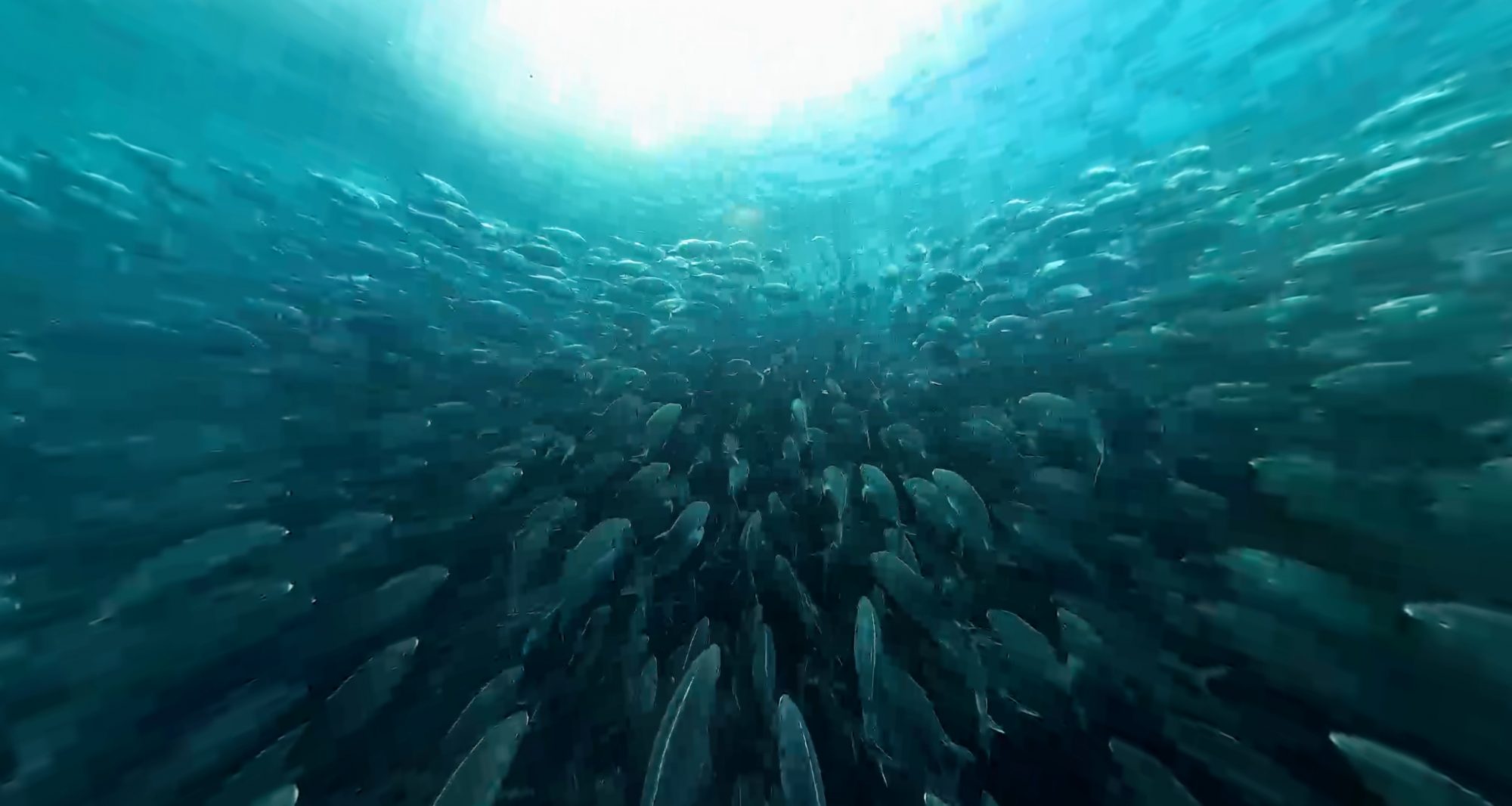

Simpson Rock, Hauraki Gulf

Trevally traffic

Schools of feeding trevally once covered acres of the Hauraki Gulf, so plentiful was the krill and so abundant the fish. Today, however, schools of trevally may be ‘only’ 30 metres across, and concentrated in parts of the gulf that remain relatively intact.

Here at Simpson Rock, there is no protection, and the moment we finished filming this sequence, two fishing boats pounced on the school.

LOADING

![]()

![]()

Hauraki Gulf, Auckland

Bow riding

Off the northern coast of Waiheke, vivacious common dolphins travel in search of the next work-up. They are lithe and playful, but also devastatingly effective predators, working around and through schooling fish such as kahawai, soury and pilchard.

In all, there are 25 species of marine mammals found in the Hauraki Gulf, almost a third of the world’s marine mammal species.

LOADING

![]()

![]()

Hauraki Gulf, Auckland

Sustainable fishing

A Leigh Fisheries longliner reels in a catch with practiced efficiency. Target species—such as snapper—go to the fish bin and then to market, and a flick of the wrist dispatches non-target species back into the sea.

Leigh Fisheries was established in 1957 and the founding families are still shareholders. They also track their catch, so the consumer knows when, where and how the fish was caught—even the name of boat.

LOADING

![]()

![]()

Nordic Reef, Hauraki Gulf

Off balance

An ecosystem in balance is marked by diversity and abundance. An ecosystem out of balance is a desert of monotony. Here at Nordic Reef, snapper populations have been depleted by overfishing, kina populations have exploded and devoured all the kelp, sponges and algae. The lush and vibrant reef has become a wasteland, or as biologists refer to it, a ‘kina barren’.

It is a dead zone, and without weed for protection, few larvae will resettle successfully to repopulate it. Even if fishing stopped tomorrow, it may take a decade to recover.

LOADING

![]()

![]()

Hauraki Gulf, Auckland

Meet the locals

Commercial fishers take around 2000 tonnes of snapper per year from the gulf, and recreational fishers an equal amount. Snapper populations are now well below the ‘target’ sustainable level of 20% of unfished populations.

For many species, populations are so low that fishers are no longer able to hit the total allowable commercial catch. Crayfish catches are now at the lowest levels since 1980 and a large recently discovered scallop bed collapsed after just three years of harvest. Destructive methods such as bottom trawling, Danish seining and scallop dredging are still being used.

LOADING

![]()

![]()

Orakei Wharf, Auckland

Recreational fishing

Fishermen cast a line from Orakei Wharf. For some, fishing here is recreational. For many others, it’s about sustenance.

However, the impact of recreational fishing cannot be underestimated. In the Hauraki Gulf, some 220,000 recreational fishers haul up the same tonnage of snapper per year as commercial fishers, but few believe the recreational take is impacting fish stocks or habitats. It is more frequently referred to as a birthright than a privilege—or a detrimental activity.

LOADING

![]()

![]()

Herne Bay Beach, Auckland

Spilling sewers

In many of Auckland’s older suburbs, stormwater and sewerage is combined. As the population has increased, infrastructure has failed to adapt adequately, and changes in climate make rainfall events more intense.

Under the terms of its resource consent, Watercare is allowed to overflow sewerage into the harbour twice per year per engineered overflow point. At some 50 locations in the western isthmus, such as here in Herne Bay, the overflow is tripped almost every time it rains, spilling around 2.2 million cubic metres of diluted wastewater into the harbour each year.

LOADING

![]()

![]()

Pōnui Island, Hauraki Gulf

The remains of the day

At Pōnui Island, under the shade of picturesque pōhutukawa, effluent from a farm drains into the Waiheke Channel adjacent to the Te Matuku Marine Reserve. Stock roam freely through the waterway and the wetland above it. The smell, fortunately for the viewer, can only be imagined.

This is a compelling picture of run-off in the rural context, but the volume of material from major rural tributaries into the Firth of Thames, for instance, is orders of magnitude more concerning. Concentrations of nitrogen in the Firth have increased dramatically since the expansion and intensification of dairying began in 1998, as has phytoplankton and carbon dioxide. Oxygen depletion in the Firth is about four times worse than in the outer Gulf.

LOADING

![]()

![]()

Leigh Wharf, Hauraki Gulf

Dumped

The irony is that the camera can’t see far enough to properly document the worst sites in the Hauraki Gulf—they’re too turbid to see more than a foot. So we’re here, in the serene and relatively intact harbour environment at Leigh, to film human impact where the water remains clear enough to get a picture, but where our influence is becoming obvious.

Jack mackerel circle about the wharf piles, while the discards of civilisation rot quietly on the seafloor. An octopus has made a home in a car tyre, and mud accretes slowly over consumer electronics. It’s an unhappy scene, but in reality, orders of magnitude better than elsewhere in the gulf.

LOADING

![]()

![]()

Hauraki Gulf, Auckland

Future food

Shellfish aquaculture appears to be relatively low impact, and presents the opportunity of high-value, high-quality protein, sustainably cultivated in a healthy marine environment. In 2016 marine farms in the gulf produced 1200 tonnes of oysters and 27,000 tonnes of mussels.

The farms offer little visual amenity, it’s true, but here in the Waiheke Channel—as elsewhere in the Hauraki Gulf—the mussel farm offers employment, economic opportunity, a recreational fishery and few negative side effects. Fish farms, conversely, are generally high impact propositions as finfish require feeding, which greatly increases nutrient loads and adverse affects on the seabed.

LOADING

![]()

![]()

Hauraki Gulf, Auckland

Islands of the Gulf

There are some 70 islands in the Hauraki Gulf, cast across the great embayment in a disorderly fashion. Most are in the languid waters of the inner gulf, such as here in the Waiheke Channel, where hundreds of placid anchorages make for some of the best cruising in the world.

Lurking beneath, however, is the invisible menace of life in the gulf. Over the past 90 years, sedimentation in the Firth of Thames have been increasing at rates ten times higher than other estuaries. Sedimentation is toxic to marine organisms, reducing diversity and abundance. If anything, rates of sedimentation in the Firth are expected to increase as rainfall events become more intense.

LOADING

![]()

![]()

Miranda, Hauraki Gulf

Prepare for take-off

Godwits and wrybills roost on chenier shell banks at Miranda, and the western shore of the Firth of Thames. Each year, godwits will embark on the longest non-stop migration of any bird in the world, flying from this site to the Yellow Sea in China, then to Alaska, and returning across the Pacific, direct, to New Zealand.

At the outflow of the intensive dairy farmland of the vast Hauraki Plains, the Firth is among the most modified marine environments in New Zealand, with high turbidity, nutrient loads, pollution and very low levels of oxygen, particularly near the sea floor. It was once carpeted with 500 square kilometres of mussel beds that filtered the outflow of kahikatea swampland, but the kahikatea was felled, the swamps drained and the mussels dredged up by 1960. By then, the sedimentation in the Firth was too thick for mussels to re-establish.

LOADING

![]()

![]()

Birkenhead Point, Auckland

Waka-ama with Richard

Richard Manuka leans on his hoe and drives his waka-ama towards the city from Birkenhead Point. With each stroke he re-enacts the practised movement of his tūpuna, in similar craft but in a very different marine environment—the water beneath him harbours a fraction of the life it once did.

Has the mauri of this place been enhanced, or depleted? Can we have our 21-century city, and restore our environment too? Māori principles of kaitiakitanga may offer a new way to understand complex systems such as the gulf and our relationship with them.

LOADING

![]()

![]()

Snells Beach, Hauraki Gulf

City of sails

Secondary school sailing teams manoeuvre before the start of a team race at Snells Beach north of Auckland. Instead of sailing to win, team-racing requires skippers to consider the most advantageous finishing order for the whole team, even if it means the individual places last.

The fate of the gulf requires Kiwis to make the same calculation—how do we put sustainability before individual gain? Is there an outcome that benefits the environment as much as society itself?