Year of the waka

The sight and sound of a score of waka taua, war canoes, and their sweating, chanting crews will forever remain etched on the memories of those who attended the 1990 Treaty of Waitangi commemoration. The waka has become a symbol of Maori unity and pride in this year of remembrance. Some say it is the vehicle which will carry the mana of Maoridom into the 21st century.

I had never been on a waka taua before. This one is called Nga Told mata wha o rua, a namesake of Kupe’s canoe, and I’m told that it needs every one of its 80 paddles to push it along.

The canoe is big — nearly 120 feet long. It’s carved from the trunks of three kauri trees and sits squat and fat in the water off the beach below Te Tii marae at Waitangi.

The order is given, “Kia rite!” All the paddles dip into the water together. “Tokihi!” the crew growls. The paddles come out, they clunk a beat on the hull and then dip again. “Tokihi!” In, out, clunk! “Tokihi!” In, out, clunk!

“Tokihi!” The waka slowly builds up speed as the paddlers’ muscles flex and ripple.

“Tokihi!” Drops of sea water and sweat mingle and run down their back-bones.

“Tokihi!” The kaea, fugleman, holds up his taiaha and raises the tempo. “Tokihi!” Now the canoe begins to lift. “Tokihi!” To drive through the swells. “Tokihi!” In, out,clunk! “Tokihi!…”

I suddenly feel scared. From this very place last century, Ngapuhi under Hongi Hika, Tareha, Pomare, Waikato — all the great chiefs of Tai Tokerau — set out on their famous raids to the south. Raids against my own people.

I find it hard to sit still among the sweating crew, imagining the despair that must have gripped the survivors of those raids — brought back to this bay in canoes just like this, on calm, peaceful mornings just like this. Some of them would die for Ngapuhi’s utu, revenge. Others would become slaves, an even worse fate. As slaves they would be subject to the command of the smallest Ngapuhi child, fed on scraps thrown down in the dirt and forced to fight with the dogs of the pa for even those. Death always just a crack on the head away. A cloud hides the sun.

It is December 1989, and I’m attending the last planning hui for a project that has captured the hearts of Maori people throughout New Zealand: Kaupapa Waka, Project Canoe — a project that has been 50 years in the making.

To mark the centennial of the Treaty of Waitangi in 1940, Te Puea Herangi, leader of the Tainui people of Waikato, wanted to restore and build waka taua. She wanted to express the tribal prestige of all Maori people by building a fleet of seven canoes, one to represent each of the major tribal groups of the country. Because the tribes needed to co-operate to successfully complete the waka taua, Te Puea’s programme was also an exercise in kotahitanga, unity, the ideal to which she and many other Maori had dedicated their lives.

Te Puea’s project was enthusiastically supported by the government of the day, but World War II intervened and funds dried up. Only three new waka taua were completed, among them the one that I find myself riding in across Peowhairangi Bay: Nga Toki.

“Tokihi!” The waka sweeps on. Some of the crew are tiring and their fatigue is starting to show. “Tokihi!” But here’s a chance for a break. The local tourist catamaran looms alongside. The haka rings out as the crew drive the waka on: “Au! Au! Aue ha!” The white blades of the paddles crash against the hull once and then lift into the air together in salute. Nga Told glides on, suddenly silent, and the tourist cameras click and whirr in a frenzy.

Nineteen ninety. It’s the anniversary of our country’s beginnings, 150 years since the signing of the Treaty at Waitangi. Te Puea’s waka taua dream has been revived, but on a much grander scale than Te Puea envisaged. This time more than 20 waka taua are to be built or refurbished; some to take part in the opening ceremonies of the Commonwealth Games and other events, but all to meet at Waitangi on February 6.

The organisers say that the Kaupapa Waka project meets two needs. The first is to demonstrate mana Maori, pride in Maori arts and organisation, by doing something that is not totally reliant on government funding, and which will encourage ingenuity, revive old skills and, more importantly, motivate Maori people.

The second is to provide a vehicle by which the majority of Maori people — those whose views and opinions seem to be ignored by the media in favour of the more vocal minority — can make a powerful statement about their participation in the life of the nation.

“Tokihi!” Nga Toki cruises on towards Russell, Kororareka — the `hell hole of the Pacific’, as the missionaries called it. Here the whaling ships of last century put in for supplies, grog and women. That Kororareka was looted and burnt to the ground by Hone Heke, and today’s version is just a collection of buildings gathered quietly around a sheltered beach. There’s still a flagpole on the hill, but now it’s sheathed in metal — nothing that a really serious protester with a chainsaw couldn’t deal to, though…

Nga Toki glides in to the wharf. Again the haka rings out and the paddles crash and point to the sky. Then they are thrust into the water, braking the canoe. The crew dig in and lean back hard on their paddles. The water surges around us — Nga Toki takes a power of stopping.

“Y’all come far?”

It’s an American woman in a green t-shirt. “Yeah,” comes the casual reply. “We left Hawaii last night.”

“Oh really! George, did you hear that? Now, I want a picture of these guys.”

The green t-shirt pushes George forward and the crew of Nga Toki laugh, loll back in their seats and smile for George’s camera.

Back at the hui, we are told that the people of Tai Tokerau are king pins in the Kaupapa Waka project. They are responsible for the issuing of invitations to bring the waka to Waitangi. They also know about the handling and manning of a big canoe, Nga Toki, and at this planning hui they offer their experience and advice to other iwi.

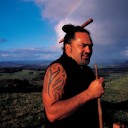

Tai Tokerau also have the responsibility for handling the local arrangements. Accommodation and food for 7,000 people for up to a week is needed. The man in charge is Wiremu Williams, an imposing figure whether on the marae or acting as the kaea, the time-caller, for Nga Toki. Wiremu, ex-Army, wants to run the operation like a military exercise, and it is this underlying order which will make the events at Waitangi seem so natural and relaxed. But then the desire for order is in Wiremu’s blood. One of his ancestors was Karuwha, ‘Four-eyes’, the bespectacled missionary Henry Williams, who played a pivotal role in putting the case for the treaty in 1840.

The navy is at the hui — two officers in their crisp whites. It’s somehow fitting. The navy was here 150 years ago, too, only then they didn’t have Kiwi accents. As they explain their role for Waitangi Day, someone wonders out loud whether they would be so free with their detailed information about the Queen’s movements on Waitangi Day if this were Northern Ireland. It’s an expression of trust on the Navy’s part that is appreciated by many.

The discussion then turns to the question of how to deal with protesters, and each group adds waka security to their list of ‘things to do’.

The hui has been a great success an energiser. As people shake hands and hongi in farewell, some glance sideways at Nga Told anchored just off the beach, as if to say, “You ain’t seen nothing yet!”

[chapter-break]

Kaupapa waka caused an explosion of activity around the country as various iwi groups began the task of building their waka, training crews and fundraising. The goal, timewise, was attendance at Waitangi Day, 1990. But Haare Williams, the project co-ordinator, saw Kaupapa Waka in wider terms, as another expression of the Maori renaissance. In this case it fostered a rediscovery of carving and seafaring skills, a re-emergence of history and an awakening of tribal pride.

It wasn’t just canoes that Kaupapa Waka built, but a people.

Canoe building is just one of the many aspects of traditional Maori life which have changed dramatically in the last 150 years. The hard labour of hewing trees down and shaping them into canoes using only stone tools and fire is gone forever. The ancient tools have been replaced by chainsaws, steel adzes and chisels, fibreglass, laminated planks, marine paints — the whole gamut of technological modernity. Change is endlessly debated on marae, and while some Maori mourn a continual erosion of traditional ways of thinking and doing things, others welcome the flexibility that change has brought.

One of these is master carver Tuti Tukaokao, who in his time has built three canoes. Te Awanui (47 feet long and 30 paddlers), to be crewed by Ngaiterangi at Waitangi, is his work, as is the design of the whakairo, carving, on Takitimu, the 80-foot Ngati Ranginui waka with room for a crew of 60. Tuti reflects:

“With the use of modern tools, a lot of the hard work is taken away. It means that we can complete jobs quicker. Why should we spend months and months doing work, when with the modern tool we can accomplish a lot more?”

Tuti suffers from osteoarthritis. His right arm, the one which swings his mallet, has already been operated on to try and arrest the disease. With this complaint, it is modern equipment which enables a craftsman to practise his craft.

Te Kotuiti Tuarua, 58 feet long and big enough to carry a crew of 60, is a canoe which belongs to the `modern’ tradition that tohunga like Tuti Tukaokao have pioneered. Constructed of laminated kahikatea and totara, Kotuiti is also the first waka taua to be built by the Hauraki tribe of Ngati Paoa this century. For them, Kotuiti is more than just a canoe: it represents a step in the restoration of the mana of their tribe.

That restoration began in 1986, when the government acted on recommendations from the Waitangi Tribunal and returned to the tribe a 2,000-acre farm block on Waiheke Island. This event recognised Ngati Paoa’s mana whenua. The canoe was to foster mana tangata. According to Gary Thompson, one of the young men who helped to organise the project, Te Kotuiti Tuarua “… did a lot of good for Ngati Paoa. While the success of our Waiheke claim had begun the process of giving the people an identity, this waka really brought them together.”

Gary says, “It was brilliant. The young people really committed themselves to it, especially at the building stage where, if we had a few hiccups, they’d stay on and work late and get the job done.

“They trained hard, too. We began our training in June 1989 and we put 130-odd through our wananga, training school weekends. We did things like working-out with weights, ‘dry-water’ paddling, learning about the different parts of a waka, learning haka and waiata, learning about tribal traditions and about wairua, the spiritual side. When the waka was finished, our kaiako, Jake Puke, made all of us hongi the figurehead on the tauihu. It was a very moving experience and after that we really felt at one with our waka.”

Ngati Paoa decided to take Kotuiti part of the way to Waitangi by sea. The January morning they chose for the voyage was dull and overcast, the sky low. As if to compensate, the crew made the ground of their marae at Kaiaua shake with their haka. Down on the beach they circled the canoe as it sat in its cradle near the high water mark, each one of them running a hand around the carved rauawa. This was their waka, and this was how they showed their aroha for it.

Kotuiti left the stony Kaiaua beach accompanied by karakia and blasts on a puwhaureroa, a traditional shell war trumpet. Then the canoe circled back, the crew raising their paddles in salute as they passed the urupa and Ngati Paoa’s ancestral dead. As the karanga of the women floated across the water, the waka turned and set off for Auckland, 52 kilometres away.

In their wake came God’s Speed, a 52-foot American sloop which was acting as guardian angel, or back-up. Paul Kronenberger, the skipper, offered his support as a contribution to the spirit of 1990, but his motivation is his service to the glory of God.

Through the morning, Kotuiti made good progress along the coastline, pausing frequently to salute tribal kainga sites and urupa, old and new. Rounding the ‘corner’ that signals the start of the long passage that runs between Waiheke Island and the mainland, Kotuiti ran into the sou’westerly which had been steadily rising and was now pushing up a bumpy slop.

Spray drenched the waka crew. Where the tide had been running in favour of the canoe, now it was coming at an angle, which meant the paddlers had to work harder to maintain speed.

They battled on, but with the wind gusting at 40 knots it was time to make for shore. Kotuiti sheltered at Maraetai, near Clevedon, and successfully completed its journey to Auckland the next morning. The crew were received tumultuously at Orakei, the marae of Ngati Whatua.

Of all the waka, only Mataatua’s northern waka achieved the original idea of many of the project teams paddling their waka to Waitangi. Mataatua was paddled from Doubtless Bay to Waitangi, a distance of more than 100 kilometres.

One proposal, to paddle the 120-foot South Island waka Te Awatea Hou across Cook Strait, was eventually abandoned, but not before the idea had attracted criticism from the Navy, who refused to provide an escort for the vessel.*

The canoe of the Taranaki people never made it to Waitangi even by road: a burning brake lining on its transporter caused a fire which destroyed the waka completely. Construction delays and bad weather forced the abandonment of plans to paddle other waka to Waitangi.

In a way, the bad weather showed just how much Maori people have moved away from their past. Several people observed that, on a subconscious level, the crews thought of the waka taua as ‘cars’ — you just hopped in and away you went. But living in the natural world requires acknowledgment of nature’s powers of wind and tide, and when the storm god, Tawhirimatea, stalked the skies, the spirit and muscles of even the best crews could not match him. The inability of the waka to journey at will was a gentle reminder of how it used to be.

[chapter-break]

The tainui convoy left Ngaruawahia in the early evening of January 31. It consisted of six waka on their transporters, a fleet of over 20 buses, a containerised kitchen and storeroom and more than 500 supporters and crew in vans and cars. The convoy, traffic officers front and rear, crawled along all night, reaching Waitangi at dawn the following day.

Home for Tainui for the next week was ‘Tent City’, on the flat land above the beach at Waitangi by Te Tii marae. The city’s skyscrapers were two huge marquees, one housing Tainui and associated tribes; the other the communal dining room. Smaller tents were marshalled in rows down the back road — most of them supplied by the Army, who were also responsible for handling the catering arrangements.

An army kitchen smells the same where ‘er you be, but walk a few yards towards the bridge over the Waitangi River and you’re in fairground land, with mobile stalls offering everything from candyfloss to a hangi. But there’s a cost. The roar of the stalls’ generators drowns out any sound of the summer, and the smell of frying swamps the tang of the sea.

As Waitangi Day came closer, the anticipation and euphoria among crews and supporters became catching. The hopes that Te Puea had had in 1940 were turning into reality in 1990, for the feeling almost everyone wanted to talk about was unity among the tribes.

Tribes like Ngapuhi, Ngati Awa and Ngaiterangi, whose tipuna had come to Aotearoa on the Mataatua canoe, had renewed their common ancestral links by co-operating in the building of their respective waka, sharing materials and advice. Ngati Ranginui of Tauranga re-affirmed their close ties with Kahungunu, but more especially with the Tainui (Waikato) tribes, in remembrance of the time when they had fought as allies against the Pakeha during the wars of the 1860s.

The massed haka of the Tainui crews made the dust fly. It may be that many of those young men knew nothing of the detail of their ancestors’ cause, but the power of their history demolished the line between past and present. The crew yelled and stamped, and what you felt was the passion of Rewi Maniapoto’s words at Orakei: “Ka whawhai tonu matou, ake, ake, ake!” (We will fight on forever!)

Unity had a humorous face, too. When Mataatua had a mishap that pitched several of the 50 crew into the water, it became obvious that the Tuhoe ‘bush boys’ had never learned to swim! They were teased about it for days.

The unity on display was not just at a tribal level. In many waka, heavily tattooed Black Power and Mongrel Mob members paddled together, their rivalry sacrificed for a cause they both believed in. Other waka proudly included Pakeha crew, in recognition of the contribution that many Pakeha had made to the various waka taua projects.

But while unity provided the spiritual strength which created the sweet atmosphere of Waitangi, it was the waka and their crews who were centre stage. Their first big day came on Friday, February 2, when the entire waka fleet paddled together across Peowhairangi Bay to the beach at Waitangi and a massed powhiri from the iwi.

The giant canoes, their crews making the spray leap with their paddles, raced towards the people thronging the beach. The crowd rushed backwards and forwards, trying to make sure they would be at the spot where their waka would land. People laughed and cried. Old men sat alone with their memories, and several old kuia wept openly as the canoes came.

The waka charged in, answering the karanga of the women, and as the hulls grounded the young men leapt ashore to perform their haka. Just for a moment it was possible to shut out the background of cars, tents, motorboats and all the paraphernalia of modern life, and imagine this beach as it might have been 150 years ago … a fleet of war canoes drawn up on the sand and the ranks of shouting warriors.

The crowds inspecting the canoes hardly thinned as night came and the beach took on a carnival air. Most of the waka were roped off and guarded by crew members, some of whom explained to visitors the manufacture of their craft and the detail of the carvings. The security of the waka was the responsibility of the crews operating 24-hour watches. Some feared protest action — a spray paint attack on the carvings, perhaps, or a steel-capped boot into a fragile fibreglass hull.

As it happened, there was no protest directed at the waka. Protesters don’t attack Maori pride, but rather those structures and attitudes that conspire to diminish it. But it would have taken a brave person even to try. Guards stood, feet apart, a paddle firmly gripped in their hands, unsmiling. You’d have to kill them first.

Ngati Maniapoto’s flagship, Maniapoto Mokau ki Runga, looked able to fight off an attack all on its own. The tauihu of this canoe owed as much to fantasy as to tradition, although tradition was there all right, aggressively restated in the size and angle of the ure of the tekoteko. Above him were several twisting spirals, joined by a filagree of pierced work lacquered to a hard gloss, with touches of bright paint between.

When Maniapoto put to sea it looked as if it had sailed out of a Polynesian Dungeons and Dragons saga. On the beach, guarded by paddle-wielding crew, it stopped the crowd in their tracks. It was a scandal, it was appalling, yet such was the power of this great sea monster that people admired it immensely anyway.

At the far end of the line of waka was Takitimu, the Ngati Ranginui canoe from Tauranga. The men in charge of the project, George Rikirangi and Morris Wharekawa, were proud of their ‘plastic fantastic’:

“We had a deadline and the only way we could meet it was to look at a new way of building our waka. We were saved by KZ7. Takitimu is built from the same material — but what a cost! Even though the 1990 Commission gave us a grant of $50,000, we had to find more than three times that amount again ourselves. Some of our people took out personal loans to help with the funding. You wouldn’t believe the cost of the tins of that fibreglass stuff.

“We have some pretty firm inquiries about building more waka for other tribes. Now that we know how to do it, we are looking at this as being one way of recouping the money we have spent.”

Takitimu also had an American connection. The original anchor for the canoe was the usual large stone enclosed in a flax net. When a local American diver saw it, he asked, shouldn’t it be a stone with a hole through it, just like the ones he had seen in the islands? The Ranginui people agreed that such were the anchors of their ancestors, but they were long lost. Well, said the diver, I know where there’s one! During a dive off Tauranga he had come across it in about 40 metres of water. The stone, an ancient canoe anchor lost in unremembered time, was retrieved and presented to Takitimu. Too precious to use, it was placed in a specially carved box filled with sea water to keep its coating of marine growth alive. Sitting in a place of honour amidships, the anchor stone became a mauri, a visible repository of the spirit of the waka.

There was a different, but very moving, spirit about the Moriori waka, Te Rangimata. Made under the direction of tohunga Tim Te Maiharoa from bundles of raupo lashed together, the Moriori waka wallowed at anchor, the sea washing through it. It was plain, but functional, and superbly adapted for sailing up against the cliffs and rocks of Rekohu — cliffs that would demolish a waka taua. Te Rangimata made a silent statement about non-aggression, and it was good to remember that assertive pride and competitive identity are not the only mana. The waka looked hopelessly hard to navigate. but, as Maui Solomon, co-ordinator for the Moriori waka project, said, “…it’ll probably be the safest on the water.”

The waka’s role on Waitangi Day was to provide a floating guard of honour and escort to the Queen’s barge. The crews trained relentlessly. All day long they were out in their waka, their paddling chants drifting across the water. When they were on shore, you could follow the progress of their training runs by the banners which headed up the columns of jogging crew members.

The discipline was impressive. Crews were subject to a rahui which forbade alcohol and, in some cases,sex. One crew captain explained, “…nothing comes easy, man. If you want to be in our waka you have to learn to do it hard, you gotta concentrate, you gotta live for the waka. You can’t do that with a guts full of beer.”

But in spite of the seriousness, training was also a good time. Practice paddles turned into fierce competition as waka sprinted against one another in impromptu races.

Paddling out among the Navy frigates anchored in the bay, crews exchanged formalities with Her Majesty’s ships. The white-uniformed sailors snapped out their salutes while the paddlers raised their paddles, looking like small forests of white-topped conifers. One canoe captain was piped aboard and made his naval off-sider a presentation of his paddle.

Ngati Ranginui in Takitimu made a trip across the bay to Russell. They saluted the town, and then presented a paddle to the dignitaries. Local shopkeepers and residents were so impressed with the waka that the crew’s intention to buy $100 worth of lunchtime fish and chips was brushed aside. Lunch was on the town.

Three days out from the big day, disaster struck. Tamatea Ariki nui, the huge Kahungunu canoe which was over 110 feet long and capable of carrying 150 crew, was in trouble. Rumours that the waka had broken its back swept Tent City. Supporters rushed to see for themselves, and Ngati Ranginui supported their cousins with a rousing haka.

The waka had been built from two totara sections with a central join, and when it had been drawn up on the beach during the powhiri, the pressure on the join had been too much. The waka had started to break in half. Tamatea was moved to the back beach and screened from public view by tarpaulins to preserve its dignity. Night and day, men worked, bolting and welding steel bars over the join to strengthen it. A fibreglass coating completed the job and, on the afternoon before Waitangi Day, Tamatea came floating out from under the bridge and into the bay again. What a welcome it got: a tremendous haka of celebration from all the waka crew, standing knee deep in the water.

Waitangi was tomorrow. But maybe it was the night — in the hour before dawn, when finally the beach was clear — that really belonged to the waka. Some, such as Nga Toki and Te Awatea Hou, were anchored off the beach, facing out to sea in the old way, ready in case an enemy should thrust his nose around the point. Most were nestled side by side on the beach, symbolising the peace and unity of the kaupapa. But all of them, lying silently in the night, expressed the spirit of the long history and identity of this country, for which New Zealanders have yet to learn the true and natural words. “We are here! We are Maori! We can carry you all!”

Te Tii marae, too, grew in stature at night. A dusty concourse by day, in the dark it reasserted its guardianship of the bay. The great carved you which mark the place where the northern chiefs met to discuss the Treaty among themselves, stare out over Tent City. They’ll be here when the crowd is gone; their spirit was here, and made its choices, in 1840.

Waitangi Day came bright and hot, as every day seems to in the north. The islands in the bay were floating on the water. A rising swell pushing in from the open sea looked threatening for those waka with little freeboard, but it seemed these waters would be controlled by sheer determination. One by one the waka slipped away through the waves to take up their stations in the front rank of the flotilla.

It was a gloriously mixed bunch. Heroes of recent years, Kn. and KZ7, were there, decked out with flags and bunting. So, too, were champion rowing and surfboat crews, a single sculler and a variety of Pacific Island outrigger craft. A dragon boat in vivid technicolour had difficulty going slow enough to keep position. Further out was a collection of tall ships, their spars providing convenient, if unsteady, lookout posts for crew members, and a swarm of small sailcraft and motorboats jostled for position in the sunlight. There was even a place for the very smallest of water transport, as two surfers casually worked over a right-hand reef break at the entrance to Hobson’s Beach.

Up at the Treaty House, the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi was being re-enacted before the invited VIPs. They sat in suits and picture hats in the covered stand, straining to hear because the sound system faced the ordinary people and the concealed protesters in the open stands. Perhaps that was only right, because it’s the people of Aotearoa who need to understand the treaty more than anyone else if it’s to become a force for unity rather than division.

Down by the beach, where the people were in shorts and jandals, there was a different spirit — one that echoed the differences between the traders’ settlement of Kororareka and the missionaries’ station at Paihia 150 years ago. Up at the Treaty House they had come to see the Queen. Down on the beach they came to see Aotearoa putting on a show for her our show, symbolised by the 22 waka and their 2,000 crew.

And then, suddenly, the Queen’s barge was in sight, accompanied by Zodiac security boats and a naval launch. The time of the waka taua had come. Nga Told and its Tai Tokerau crew turned to escort the Queen into the beach. On she came, past the patiently waiting waka, past the captains standing tall, past all the young men who until now had not known pride, all the young men who had suddenly found themselves. And the descendants of the chiefs who had once been lords of the land lifted their paddles as one in salute.