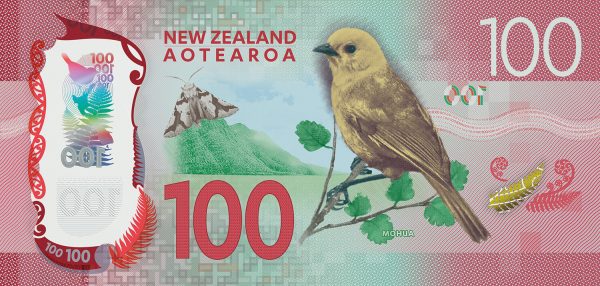

Whio

The story of the bird on our $10 note.

Anyone who has careened over white-water rapids will appreciate the skill of the whio, or blue duck. It is one of only four duck species in the world to make its home in torrent rivers, and is a dexterous navigator of rapids.

“Whio live in the harshest of environments, and even newly hatched chicks can skip across turbid water,” says Andrew Glaser, leader of the Whio Recovery Group at the Department of Conservation.

To feed, they use a fleshy membrane at the end of their bill to feel for insect larvae on rocks. “They are the only duck anywhere with lips!” laughs Glaser. “Well, just a top lip.” Without it, the abrasive rocks would wear away the bill.

Most of us have never seen a whio, let alone admired its lip, its slate-blue plumage or contrasting yellow eyes. Yet they once lived throughout both main islands. Māori named them after the male’s call, a whistle. (The female, in contrast, emits a rattling growl.)

At that time, pairs were spaced along rivers from the mountains to the sea, preferring a medium flow with riffles and pools. As they do today, they would feed at dawn and dusk, and patrol their territories from the air, engaging in aerobatic combat with intruding whio. Soon, however, whio had to contend with intruders of a different kind.

In 2000, a DOC team set up video cameras over whio nests in two Fiordland valleys—one where stoat trapping was taking place, the other that was not predator controlled. Every nest in the untrapped valley was raided by stoats. “Some of the adult birds would try to fight the stoats, and some would get killed by them,” says Murray Willans, a former biodiversity manager with DOC.

Further studies showed that, without trapping, 91 per cent of nests were predated on, and that nearly half of the adult females were killed while nesting or during the two-week moult, during which both sexes are flightless. Predator-free islands offer refuge to other bird species under pressure, but don’t have fast-flowing river systems that serve as whio habitats.

By 2009, just 3000 whio remained, at most. The survivors had retreated to high altitudes, where the pristine, forested rivers they require remain.

Salvation came just one year later, when Genesis Energy took up sponsorship of the species. “Before, I had a $900 annual budget to protect a whio population near Opotiki,” says Glaser. “The serious money from Genesis Energy has made all the difference, and they have never made it about the company, it’s all about the birds and the people. Now we have over 14,000 kilometres of river and 562 pairs being protected from stoats across eight sites… We get almost three times the number of fledglings.”

(Ironically, Genesis Energy’s predecessor, the Electricity Corporation of New Zealand, opposed DOC in court over proposed hydroelectric schemes that would affect whio in North Island rivers. It has since been discovered that dams may actually help protect whio from floods which can sweep away nests and ducklings.)

The wild population is supplemented with whio bred in captivity or hatched from wild eggs. In areas with active predator control, populations are rebounding, and whio have even been successfully reintroduced to Taranaki, where they were lost completely in the 1970s. Yet the decline in numbers continues in unmanaged regions.

Today whio are classified as nationally vulnerable, numbering around 3000.