Where memories speak

150 years of keeping the past alive at the Auckland War Memorial Museum

After wrestling with locks and alarms for a minute or two, Oliver Stead, Auckland Museum’s head of collections management, triumphantly swings open the inner warehouse door and we step across the threshold into another world.

Under a sky of silver insulation and fluorescent strip lighting stretches a geometric sprawl of calico dust cloths draped over all manner of objects. The antlered head of a deer stares out from the white landscape. A fleet of a dozen or more Pacific canoes hangs suspended from a wall that is all of 100 m in length. World War I field ordnance stand with greased barrels before towering rows of metal shelving. There are racks of Victorian chimney pots, stacked orange shipping crates, a red pedal car, more stuffed animals. Polynesian fishing boxes hewn from tree trunks. A penny farthing.

“Quite something, isn’t it?” says Stead admiringly. “There are a couple of Spitfire engines here somewhere.”

We are inside the Auckland War Memorial Museum’s off-site storage facility, a large, unremarkable building on a busy suburban street. There is no signage to suggest the presence of the 1500 m3 of objects within, many of them priceless, some mere flotsam accumulated through the years in the wake of the ever-growing and evolving museum.

Nor is the warehouse an ideal environment for preserving precious artefacts. Despite repeated attempts to fix it, the roof leaks, and in winter the humidity hits 70 per cent. Mould is rampant—so much so that a conservation technician was employed for two years to clean the worst affected items and make hundreds of protective dust covers.

Museum staff have to accommodate the inconveniences of such a place as they work towards the long-term preservation of everything in their care. But should they feel despondent, there is always the physical magic of the objects themselves.

With a grin, Stead pulls out his favourite: a 2 m-long wooden canoe. A trio of carved human figures crouch inside the vessel, their gaze fixed intently on the horizon. Behind them are several other hunched creatures that look uncannily like clones or ancestral phantasms.

“We don’t know much about it,” says Stead, “but to me it epitomises voyaging into the unknown.”

Leaving the canoe, I push further toward the unknown myself, following Stead down a flight of stairs and into the midst of yet more material. We come upon a row of dusty cabinets built by A. W. B. (Baden) Powell, one of the museum’s energetic former curators, to house his collections. The nearest one is headed “The Teeth of Herbivorous and Carnivorous Mollusca.”

At every turn this storehouse holds a surprise. It is like walking about the attic of an eccentric collector possessed of the means to ransack the world for bizarre objects according to an arcane plan—or perhaps to no plan at all.

I wander over to some metal bins encased in wooden frames. Undoing the latches of one, I lift its white painted lid and give an involuntary start at the unexpected contents. There, in a bath of tea-coloured isopropyl alcohol, large fish lie at all angles of repose, their lifeless eyes gazing emptily as if from the depths of some unapproachable netherworld. A label attached to one reads Jordanidia solandri. A sharp chemical tang slowly permeates the air.

Preservation in alcohol—a traditional fixative maintains the integrity of the DNA, says Stead, enabling scientists to compare the genes of creatures gathered decades ago with recently acquired specimens. Genetic taxonomy, based on DNA sequencing, yields a more complete picture of an organism than that which can be built up through traits such as colour, form and skeletal structure.

“There is a huge amount of genetic potential locked up here,” he says. “Ultimately, we’d like to get into frozen tissue samples.”

Such talk is a long way from the concerns of early museum staff, who fretted about keeping moths from the stuffed birds and wondered what to do with weighty copies of Greek sculpture.

At the time of my visit, news had just broken of a $26.5 million government grant towards the second stage of the museum’s ambitious redevelopment project—not a bad 150th anniversary present for the country’s oldest museum. The project involves building a four-storey copper-domed atrium inside a little-used internal courtyard towards the rear of the museum. An architect’s model reveals it as a vision of UFO-meets-Parthenon.

The new development, part of which could open as early as 2004, will improve exhibition space and visitor amenities and add underground parking, a 150-seat theatre, a Maori craft workshop and a rooftop restaurant. Most importantly, it will also provide safe, atmospherically controlled storage for all the objects now housed in the off-site store. Well, for most of them. Stead admits some culling will be necessary. The cost of storing and caring for individual items is huge, he says, and every time a second-rate piece is added or retained, the increased crowding compromises what can be done to preserve and display the finest material in the collections.

Understandably, such talk makes curators nervous, and there is tacit resistance in some quarters to any form of winnowing. Nevertheless, managing a collection, as opposed to allowing its chaotic, unordered growth, is a vital museum activity—especially for an institution with holdings the size of Auckland Museum’s.

Some years ago, to gain support for its redevelopment plans, the museum summarised the significance of its collections. A lengthy list drew attention to:

• a Pacific canoe collection that ranks among the top four in the world

• the country’s largest African and Indonesian collections

• the most important collections of New Zealand pottery and applied art in the world

• the country’s largest collection of historical photographs

• the country’s largest herbarium database (now standing at 180,000 entries)

• the largest collection of New Zealand and Pacific land snails and New Zealand bats in the world

• one of the country’s most important reference collections of fish

• ditto for land mammals and crustaceans

. . . and so on.

Perhaps most impressively—off-site store notwithstanding—the museum’s collections are housed in an undeniably beautiful building. It is one of the best examples of Greek revival architecture in the world (and has a Getty Foundation grant to prove it). Crowning a landscaped rise within a wooded park, and with commanding views of Waitemata Harbour, it has long been a city icon.

All this—the size and location of the building, the scientific research conducted within its walls, the 100 plus staff, the sheer diversity of the collections—would have surprised and greatly pleased the museum’s founder, John Alexander Smith.

In October 1852, when Smith opened the doors of his Auckland Museum—a small former farm workers’ cottage in Grafton Road, its site now remembered with a plaque—New Zealand had been a British colony for just 12 years. During that time settlers had been busy scratching a living amid Auckland’s volcanic cones while doing their best to assemble for their town the trappings of Western civilisation.

One of the most desirable civic trappings, in that century of unquenchable curiosity and scientific enquiry, was a museum. The very year Smith declared his establishment open for business, the South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria and Albert) was founded in London, as was the Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg.

Formerly in the employ of the East India Merchant Service, Smith—merchant, chandler, commission agent, gentleman—was a thoroughgoing entrepreneur, and he was in no doubt as to what the home-grown museum’s role should be. His inducement to begin it, he said, was frustration among visitors at the lack of information on the colony’s products.

He therefore resolved, as he later wrote, to “combine the several branches of natural history, weapons tools &c of New Zealand—the neighbouring colonies & the islands of the Pacific—with an industrial collection from this colony in particular shewing the products &c as far as hitherto developed.” He also thought that a library of scientific works and books relating to New Zealand might be a good idea.

In many ways Smith was well qualified to act as a catalyst for the creation of such an institution. One of the leading lights of Auckland society, he provided his fellow colonists with something of a lifeline, supplying them with everything from tobacco, earthenware, blankets and tablemats to cement, nails and iron bars. He even imported a fire engine.

Not content with such trade, he also set up a soap and candle factory and messed about with fish curing, making fabrics and threads from flax and extracting dye from orchilla, a type of lichen.

It was largely due to Smith’s instinct for self-promotion that Auckland province despatched a collection of objects to London in 1851 for the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations. The Auckland entries constituted something of a trade mission, with samples of produce ranging from maize, salted mullet, leather, bark for tanning and woods for furniture-making to lumps of coal, limestone, pumice, iron sand, whale oil and kauri gum—in short, anything that might turn a trading dollar. For good measure, Smith threw in a “native box” and a model pa made from beeswax.

The very next year he was swinging wide his museum portal to reveal stuffed birds, shells, insects, reptiles and various curiosities amongst which, according to the press, “an hour may be very agreeably and instructively spent.”

Governor George Grey loaned some sketches of the Loyalty Islands and other places of interest drawn by Charles Heaphy, then a draughtsman in the Survey Office, and an inventive corporal, James Hall, of the Royal Sappers and Miners, displayed a creditable type of asphalt he had concocted from kauri gum, sand and coal tar and with which he had lined drains at the nearby Albert Barracks.

From the outset, then, the museum was a thing of great diversity, taking on the roles of surrogate zoo, scientific institution, art gallery, library—even, for a time, school of design—until such establishments could flourish independently.

Also from the outset the vulnerability of the collections was all too obvious. In December 1861, the newly arrived curator, Elwin Dickson, found “the moth had made sad havoc . . . especially with the stuffed birds and other skins,” many of which he was forced to remove from display.

Three years later, “the moth” was still causing trouble, forcing another curator to doctor specimens with a preparation of arsenic and to make liberal use of disinfecting fluid to subdue offensive odours.

Early on, Smith instituted a practice which was to enlarge the museum’s holdings considerably and which was pursued with great success by later curators: he wrote shameless begging letters to anyone within the colony or overseas who he thought might be in a position to supply some useful item, either as a gift or by way of exchange.

Out went correspondence to the trustees of the British Museum, to the commissioner of Assam in Calcutta, to the Australian Museum in Sydney, to New Zealand’s retired colonial secretary, Andrew Sinclair, and to a host of others, expressing a desire for everything from woven “native” mats and weapons to minerals and exotic birds.

Smith kept a detailed account of his acquisitions, meticulously recording everything in a large journal. Characteristically, the very first donation entry acknowledges the gift of the journal itself from a local stationer’s. The earliest collection item noted was a piece of yellow sulphurate of copper from Hawaii, part of a collection presented by the lawyer and politician Frederick Whitaker.

Whitaker was much involved in mining copper and manganese on Kawau and Great Barrier Islands in the 1850s, and had sent copper ore to the 1851 Great Exhibition. In 1867, he was elected first president of the Auckland Institute (a forerunner of the Royal Society of New Zealand), and in this capacity was to have considerably more to do with the museum.

Having failed to find a more suitable home for the collections than a tiny farmhouse, Smith enigmatically quit Auckland for Napier in 1857 (there are suggestions he despaired at Auckland’s lack of enterprise), and for a decade or more the museum languished, until in 1868 it was placed in the care of the Auckland Institute.

For the next almost 130 years—until 1996, when control was transferred to a new board of trustees—the institute’s secretaries would oversee the affairs of the museum as curators and, later, directors. The institute’s bent was intellectual rather than commercial (as Smith’s had been), so the focus shifted to lectures based on the museum’s collections.

The search for suitable premises for that burgeoning horde of objects stretched over many years as the museum shifted first to a room in a government building (which later became the Northern Club), then to a dilapidated former post office in Princes Street (where the Hyatt Regency now stands). There, under the stewardship of one of the museum’s most remarkable curators, Thomas Frederick Cheeseman, the museum made a stand. In 1876, the post office was replaced by a purpose-built home, and for 50 years Cheeseman guided the museum’s growth, eliciting gifts and cultivating public support while enthusiastically pursuing his own botanical interestsPhotographs reveal something of the museum’s character at that time. One shows a balconied hall that looks the epitome of Victorian busyness and overcrowding. Classical statues fight for elbow room around a giraffe skeleton that stands incongruously in their midst. Others record the arrival of the massive war canoe Te Toki a Tapiri; the skeleton of a moa; a white-gowned preparator at work in the basement amid a veritable menagerie of stuffed animals.

[Chapter Break]

At a time when the city had no zoo and when books with coloured illustrations were scarce, Cheeseman’s collections illustrating plants and animals from around the world were both educational and entertaining.

Some have survived, and are on display in an exhibition celebrating the museum’s sesquicentenary. To my delight, I find there, in a partially opened shipping crate, the “polar bear stalking musk oxen in snow” set piece that was such a transfixing childhood experience. Those massive paws, the seductive textures of fur and snow, the unutterable plight of the hunted. For years—until I saw the violent cover art of Konrad Lorenz’s On Aggression that Arctic diorama for me signified nature’s dark side.

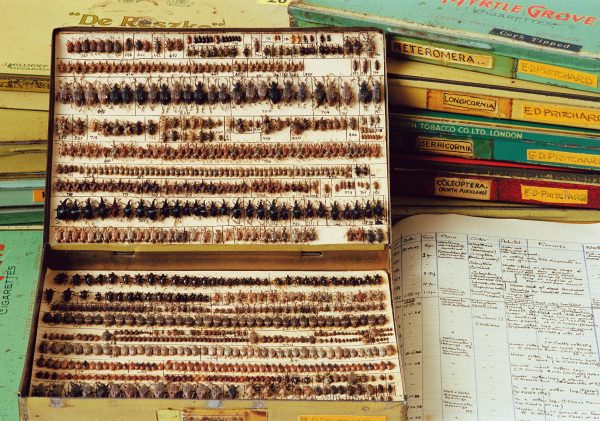

Gifted in 1906, the polar bear and oxen are the only mammals to survive from the Princes Street era. Nevertheless, the 150th display is not short of material. There is a letter by James Cook dating from his 1768 voyage, written in a surprisingly fine hand and signed with a schoolboy flourish; a delicate group of 41 hummingbirds in a small tree; a drawerful of forlorn study skins of the extinct huia; a mummified cat and falcon dating from around 750 BC. The oldest traceable insect in the museum’s collection—a giant weta obtained by William Colenso in the Bay of Islands in 1838—is on show along with trays of jewel-like beetles with neat, almost microscopic, labels.

Carol Diebel, co-curator of the display, tells me the intention was to take advantage of the limited space available to create the look and feel of a Victorian cabinet of curiosities.

“It is just as cluttered back here,” she says, showing me to her own workspace.

Diebel is the museum’s curator of marine biology, a department she runs with the aid of a technician and a handful of volunteers. In the passage outside her office two helpers taking a tea break at their desks pause to say hello. Noel Gardner, now in her 80s, has been lending a hand at the museum for 60 years—her husband Norm is a land snail specialist. Fiona Thompson, in her 70s, is following the interests of her father, who was a professor of zoology at the University of Auckland.

On nearby windowsills are geological specimens, including a metre-long submarine chimney hauled from the seabed at a depth of 300 m off the entrance to Kaipara Harbour. Donated collections of shells lie on work tables in the passage and in cardboard boxes on the floor awaiting attention. “At the minimum, we need to know where a thing was collected and when,” Diebel says, adding that even with this information, assessing gifted material is a slow business.

Having had occasion to approach museum staff about the identity of marine mammal bones, I ask about the range of requests she fields from the public.

“We get a lot of people coming in and asking what kind of animal they’ve found,” she says. Fossils are popular, and ambergris, a waxy substance found in whale intestines, has been big this year, she tells me. Ambergris is used as a base in some perfumes, and there is a ready (and legal) market for it in Asia. Diebel offers an easy identification test: heat a needle and push it in. If the needle comes out trailing a thread, there is a good chance you are holding a piece of ambergris.

One marine specimen handed in—a colonial sea squirt—had to be sent to Australia for identification due to the shortage of taxonomists in New Zealand. That gets Diebel on to a favourite topic: the role of basic, as distinct from applied, science. She explains the difference with a simple illustration. Looking at ways of stopping a mosquito biting people is applied. Investigating mosquito biology is basic. Money for the latter has always been harder to get.

Diebel sees the new emphasis on biodiversity and on monitoring human impacts as affirming the importance of the museum’s reference collections. She shows me several drawers full of holotypes—the original specimens used to describe new species. I recall a spiral exhibit in Diebel’s anniversary display made up of 119 shells—just one tenth of the species described by Powell alone.

Near the holotype drawers are shelves crammed with robust folders, their spines decorated with blocks of colour and hand-lettered labels. Powell, again. I pull out one with a red spine, numbered 128–130. Inside the thick card binding is Palaeontological Bulletin 26, “the genus Pecten in New Zealand,” by C. A. Fleming. Turning the back cover I read in large letters: “Himmler Dies From Poison—Arrested By British.” Below is a photograph of the Nazi Gestapo chief and text that mentions potassium cyanide.

Ever the budget-minded pragmatist, Powell evidently cannibalised old newspaper files to make the cardboard covers for his research material. Amused, I take down another folder. Ignoring its scientific contents, I read “Torture Demonstrated to Supreme Commander.” A photograph shows a grim-featured General Eisenhower witnessing a bizarre re-enactment.

Sandwiched between the leaves of wartime history, Powell’s meticulous records and files did much, in the days before photocopiers and computers, to add value to his work. “The importance of his library is still not realised,” says Diebel, who dreams of reuniting its scattered parts.

More appreciated is Powell’s field work. He contributed greatly, for example, to the Three Kings expeditions undertaken by Auckland Museum staff between 1934 and 1954. These scientific forays to the small cluster of islands lying 56 km off North Cape typify the adventurous spirit of enquiry inherited from Cheeseman.

Indeed, Cheeseman had visited the islands as early as 1887, but the real work began in the 1930s with the discovery of a new subspecies of bellbird and new giant land snails. Thanks to the isolation of the Three Kings, more unusual finds were soon made, including a blind hairy land snail, Cytora hirsutissim, and the world’s rarest tree, Pennantia baylisiana—just one was found, on Great Island.

Another aspect of the Three Kings field work was research into the recovery of endemic species following the removal of introduced animal pests—mainly goats. As a result of these studies, the museum made a pioneering contribution to what is now called ecological management. It is work carried on today by people such as botany curator Ewen Cameron.

In the temperature-controlled environment of what was once the museum’s bird hall, Cameron watches over a herbarium of 300,000 specimens, which includes 500 sheets of plants gathered during Cook’s first voyage. He takes one of the precious sheets from a fireproof cabinet. On it is a native orchid found near Mercury Bay in November 1769, its leaves still green.

The sheets themselves were requested from the British government in the 1890s to help with the writing of the Flora of New Zealand, a job completed by the ubiquitous Cheeseman.

Botanical specimens are constantly returning to Cameron or being sent out to specialists around the world, following a practice dating from the museum’s early years, when international networks helped overcome New Zealand’s isolation and gave local curators access to the latest scientific thinking.

At present, for example, more than 1000 specimens are on loan to lichen expert David Galloway, in London, who is updating the classification of New Zealand lichens.

Cameron offers to show me his computerised database, and as we step into his office I remark on a fine piece of mottled kauri furniture with rewarewa and puriri inlays. “Ah, yes,” he says. “We have more space than Louis [Le Vaillant] has in applied arts, so I’m kindly storing it.”

I agree that it complements the fine leather-bound set of Curtis’s Botanical Magazine, dating from 1791, which

graces the shelves behind. Such books—and there is a sizeable library of them in the larger workroom—are indispensable in tracking the serpentine shifts in plant taxonomy.

Over recent years the process of classification has been invigorated and accelerated by DNA testing, which confirms some connections and splits others.

“It will all settle down. We are just in a state of flux because of the increased information,” says Cameron.

As well as managing the herbarium and database, Cameron also does a lot of what he calls “weed work,” identifying plants for the Auckland Regional Council’s biosecurity officers and others. “We are ideally placed to pick up new weed records because of Auckland’s long, warm growing season,” he says.

More than 650 species have naturalised in the region over the past 150 years, and the museum’s historical records are valuable in tracking the changes and alerting authorities to new threats—more so since the Department of Conservation doesn’t have a herbarium, and Auckland University donated its own 50,000-strong collection to the museum.

Indeed, one of the key jobs of curatorial staff these days is the management of information. Nor is this restricted to scientific data. Auckland Museum’s curator of applied arts, Louis Le Vaillant, who holds the only such position in the country, looks after New Zealand’s most comprehensive database of New Zealand craftspeople, designers and manufacturers—7000 in all, with works dating from as early as the 1820s.

Like Cameron, Le Vaillant also relies on the work of private collectors and enthusiasts—people such as the late Zillah Castle and her brother, Ronald, Wellington pharmacists with a love of baroque music. For 50 years the Castles’ Newtown house was home to what became the country’s most important collection of rare and unusual musical instruments. The Castles used the instruments widely in concert performances and to illustrate lectures and radio broadcasts, putting the first one they bought, a spinet, in the back of the car whenever they toured.

In 1998, Auckland Museum acquired the collection, which had grown to some 500 pieces, a third of which are now on show in a dedicated hall of music. And an intriguing assembly of wood, bone and metal they make. Among the items demanding attention is a phonofiddle, “equal in richness and tone to three ordinary violins,” says the accompanying text, and a Stroh cello. Stroh was a singular man, known for his forays into telegraph communications and acoustics. His cello and nearby violin are wild hybrid things that give the impression of an orchestra’s string section having fallen amongst the horns and become inextricably entangled. No one seeing them could be in any doubt that whatever sound was wrung from them would be of considerable volume.

Creating a home for such a fine assemblage can bring unexpected benefits. As a result of seeing the Castle collection, one museum visitor gifted a violin made in Greymouth in 1876—the oldest recorded as having been made in New Zealand.

“Applied arts” is a broad label that nets a huge variety of objects, from Qing dynasty court ware to English pewter, from tribal rugs to studio ceramics; in short, any individual object with aesthetic merit whose design is indicative of a style or technical development.

The range becomes obvious as Le Vaillant shows me round his patch. He is leading the way through a military exhibit towards a distant outpost of his department when, unexpectedly, he stops before a panel on which old news footage is being projected. A grainy image shows a brace of grinning Edwardians hauling a flimsy seaplane down to what I recognise as Mission Bay.

Without formality Le Vaillant grasps the panel and slides Rangitoto and the Waitemata Harbour aside. I just have time to read “Sea Dogs and Flying Aces,” then we are through into an air-conditioned store full of mostly English furniture—grandfather clocks, pieces with delicate veneers, a jewellery cabinet inlaid with pewter; even an 1842 Webster organ, the first musical instrument made in New Zealand.

I want to linger over every item. Growing battle-hardened to such a surfeit of riches as the museum possesses takes time.

We head out through a glazed, sculpture-choked terrace almost amidships on the building’s roof and into a ceramics store. Birdsong envelops the racks of Crown Lynn and studio pottery. We are, Le Vaillant explains, directly over a natural history gallery.

Next we visit what Le Vaillant calls his “central processing unit”—a small room where objects are first accessioned. It is a crowded space containing drawers of jade and Indonesian silver, bundles of fabric and clothing accessories. Keeping non-New Zealand items remains important, he says, because their countries of origin “are where some of us come from or refer back to.”

Finally, off Centennial Street—a beguiling scaled-down slice of colonial Auckland—a door opens to the textiles store, where Le Vaillant shows me Persian rugs and other carpets wrapped in protective sleeves of Tyvek fabric, each with a label and identifying photograph.

At my feet are bare wooden boards, the old stage from the days when this part of the museum housed a library reading room and auditorium. Down a short flight of steps, half hidden by shelving, is the stage’s carved foot.

Then, bewilderingly, we are back among things military. The ramble through applied arts has unexpectedly yielded an archaeology of the museum building itself. Even the cramped office space Le Vaillant shares with history curator Rose Young and several assistants harks back in its architectural details to a former life as Cheeseman’s stately wood-panelled office.

And, I am reminded, it was Cheeseman who hit upon a cunning way to realise his vision of such a commodious, imposing building in the first place. “Cunning” perhaps does the curator an injustice. What he did, back in the pinched and war-ravaged early decades of last century, was suggest that to raise an imposing new museum might be a suitable way of honouring Auckland’s World War I dead.

Almost a third of the 18,166 New Zealanders who died in that brutal conflict have no known grave, and to the people of the province the idea of a living memorial was an immediately appealing one. Even the site Cheeseman proposed (and others before him)—Observatory Hill, on the rim of a volcano—seemed preordained. Sold to the government in 1840, it was known by Maori as Pukekawa, “hill of bitter memories,” after the Nga Puhi musket raids of the 1820s.

By June 1920, £52,000 had been raised by the Auckland Institute, along with £158,650 through public appeal and £37,000 in the form of a government subsidy. Two years later, an international competition for the design of the proposed building was won by the firm of Grierson, Aimer and Draffin, a team of young New Zealand architects who, fittingly, had themselves served in the Great War. Kenneth Aimer and Keith Draffin had been wounded at Passchendaele, on the Western Front, and Aimer and Hugh Grierson had both lost brothers on active service.

Their design drew on classical Greek architecture, which, by the mid-19th century, had come to symbolise democracy and learning. The facade’s entablature and Doric columns, echoing the Parthenon, would have stirred ex-servicemen’s memories of Mediterranean temples glimpsed from the decks of troop ships. The Auckland Museum was likewise designed to make an impression from the sea, and to enhance the effect a small obstructing hill in front of it was removed.

Draffin tried to obtain the blueprints of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Whitehall, in London, on which to base a cenotaph for the museum’s courtyard, but the exercise proved too expensive. Instead, it is said he doggedly went to the movies every night for a week to sketch the tomb from cinema newsreels.

The building gains in stature from the very materials used. The walls are of concrete faced with Portland stone shipped from England, on a foundation of Coromandel granite. The fluted entrance columns were chiselled by stonemasons from solid blocks of limestone (which, appropriately for a museum, contain fossils).

A 1950s extension to the rear of the building, honouring the dead of World War II, doubled its size but attained less purity in the execution, being finished in more economical concrete moulded to resemble stone.

The finished building manages spectacularly to embody its function, probably better than even Cheeseman, who died in 1923, could have dared hope. More than that, by skilfully blending Maori motifs (the koru and taiaha) with its predominantly neoclassical features, it came to provide what Stead calls “a lasting architectural tribute to the idea of memory in cultural history.”

[Chapter Break]

Even as the Auckland War Memorial Museum was being built, a highly unusual Maori artefact, known simply as the Kaitaia carving, was acquired. Found in a Northland swamp, this work of art, featuring a solitary human figure flanked by two lizard-like forms, came to symbolise the outstanding richness of the museum’s ethnological collections.

Fuli Pereira, assistant curator of ethnology, spends much of her day registering new acquisitions, but says the time when the museum could afford to buy older pieces, let alone unique objects such as the Kaitaia carving, has long gone. With an increased demand for indigenous artefacts drawing private collectors with deep pockets, as well as the heavily bankrolled Te Papa, Auckland Museum is being priced out of the market, she says. “At the last Dunbar Sloane auction I went to, even the old hands were commenting on the new faces there with corporate money. We were completely outcashed.”

For the most part, the museum contents itself with filling gaps in its collections from the 1920s on, and developing its contemporary Pacific collection “to make it relevant to the people we would like to see come through the door.”

Even so, Pereira is clear about the limits to such an approach. “For me, the purpose of the collections is to show our past and how it is relevant to the present. It would be a mistake for the museum to be completely taken up with acquiring contemporary objects.”

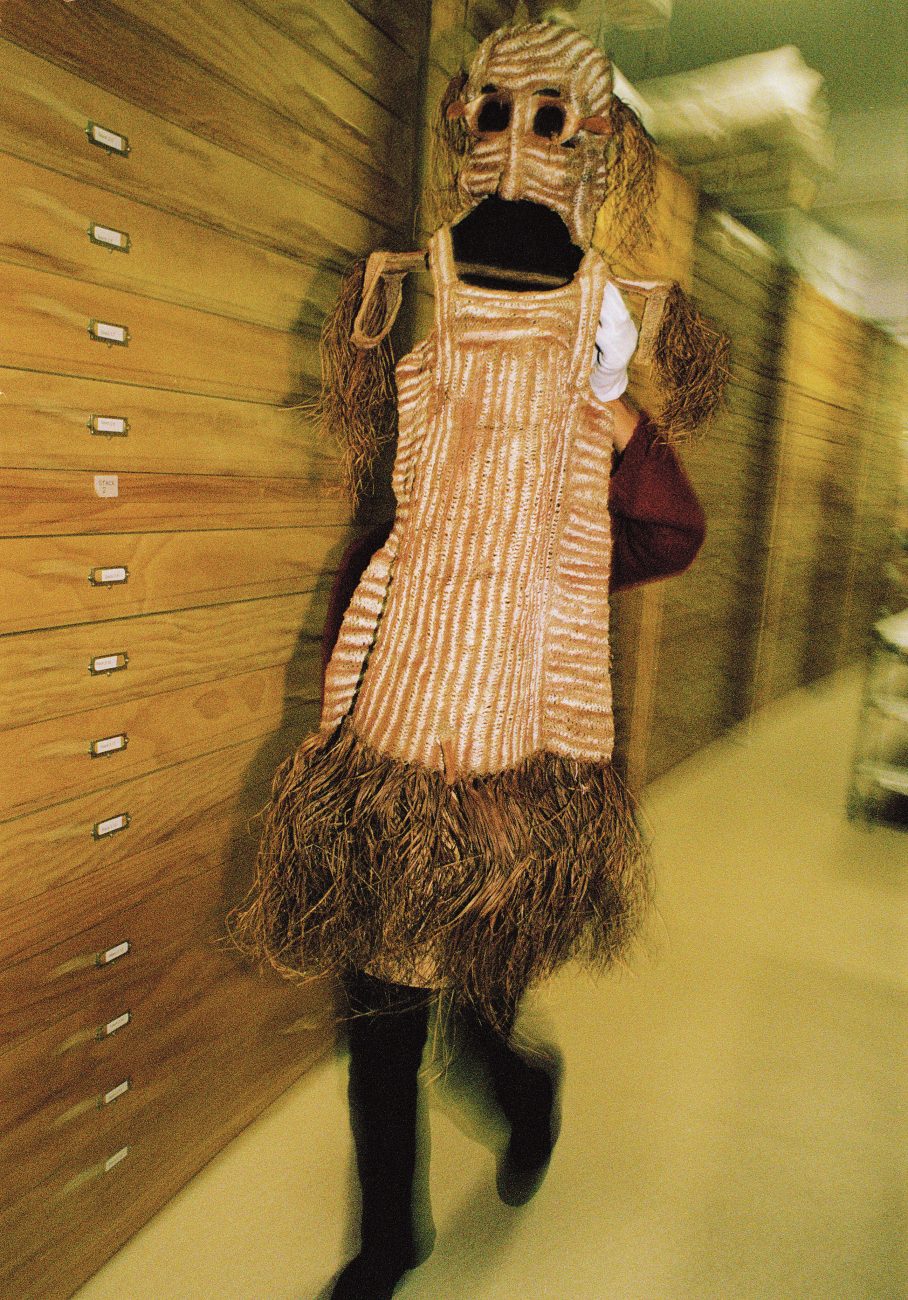

In ethnology, as elsewhere, there is little doubt that the museum has a tangible grip on that past. Pereira takes me into climate-controlled storage rooms holding cloaks and tapa cloths, basketwork, weapons and jewellery; dendroglyphs from the Chatham Islands; a 6 m-high rack of ko (Maori digging sticks); carvings from a meeting house; weapons—“I couldn’t begin to tell you how many of those we have.”

One Australian artefact dealer was so impressed by the depth of the Pacific holdings that he went home, selected the best house boards from his Irian Jaya collection and presented them to the museum. Pereira observed a similar reaction when she unrolled a collection of rare ‘ie sina (Samoan mats) before a group of Samoan women, reducing them to tears.

“It made me think I was on the right track,” she says.

Pereira, born in Samoa to Tokelauan parents, came to the museum in 1992 on a Maori and Pacific Island traineeship. One of the reasons she was employed, she says, was the growing awareness of the museum’s governing body that it needed Maori and Pacific Islanders on the staff to help care for their taonga.

The inaccessibility of much of the Pacific collection, due to a chronic lack of space and temporary off-site storage, hampers Pereira, who is trying to attract more Pacific Island families into the museum. Carving schools and Maori groups are already frequent visitors, along with those visiting family-owned taonga, but a common attitude was summed up by a Samoan working on the museum refit, who told her: “I prefer Te Papa myself. The kids like the rides.”

A clearly frustrated Pereira will have none of that. “There are Pacific Islanders who don’t know their past, who are searching for their identity,” she says. In her view that is a hole that entertainment, no matter how alluring, can never fill.

Richard Wolfe agrees. For 20 years, until he retired in 1997, he was the museum’s curator of display. He believes high-tech interactive displays confer little long-term benefit. Some, he says, are simply demeaning.

“I have come to the conclusion that the most authentic interaction is to be had from an object with a label, because that requires you to think. Interaction should be intellectual, taking advantage of an object, not just swinging on a lever.”

When Wolfe took up his post, Auckland Museum had three floors of “fairly ancient” galleries. His job was to keep the light bulbs going while changing exhibitions every three months or so to freshen up the place.

Then, after decades of declining popularity, museums worldwide discovered showmanship. An age of grand theatre dawned, with blockbuster touring shows such as Tutankhamun, Oro del Peru and China’s Buried Army renewing public interest. The design world became involved, and suddenly, says Wolfe, museums were glamorous again.

With the rapid growth of city attractions, ranging from wide-screen cinemas to theme parks, the temptation is to compete by making a visit to the museum an ever more fabricated Disneyland experience. Wolfe takes a dim view of such a prospect—as does collections head Oliver Stead. Stead acknowledges that museums need to be made more attractive in what is a highly competitive entertainment environment, but says that, historically, science has been the engine of museum endeavour, and he is keen to see that function become more prominent.

Following the restructuring of science in New Zealand, the government is keen to give the public access to the fruits of research, says Stead, and museums are well suited to act as the conduit. There is a proviso, however: “You earn the right to do innovative work by first doing the mainstream well.” Spielberg wouldn’t have had the chance to shoot Schindler’s List, Stead points out, if he hadn’t first made Jaws.

Nevertheless, the attempt to remain relevant to the needs of society creates tensions—for instance, between the acquisition of low-value ephemera to document New Zealand social history and high-quality objects of applied art; between the nostalgia of 40-year-old kitchen technology, say, and the aesthetics of rare Korean pottery.

Both have their place, and the gap separating them is not unbridgeable. When the museum’s old war trophies hall was reconstituted as the “Scars on the Heart” exhibition, seemingly insignificant objects—a tattered map, a ration card—found their place next to things of great rarity. All had one thing in common: they helped tell the stories of real people who had once used them and whose lives they had helped shape.

The ancient Greeks coined the word “museum,” meaning a temple of the Muses: a place where the nine goddesses of the arts and sciences gathered. By the end of the 19th century the deities had become dowdy janitors, their modern temples mere echoing halls filled with treasures recovered like wreckage from the shores of a fast-moving world.

Now, at the start of the 21st century, those treasures are being seen with fresh eyes, and valued for the memories that resonate within them. Memories of craft technique and social experience, of evolution and migration. Of sacrifice and valour.

Memories that the Auckland War Memorial Museum has been safeguarding for 150 years.