Whangamomona

The small settlement of Whangamomona, buried in the hills of eastern Taranaki, declared itself a republic in 1989 and has since attained a sort of cult celebrity status. For Republic Day celebrations—held in summer every second year—thousands of visitors flock to the town, and are required to hand over $3 for a passport at border control points. Even those who arrive on the several special trains are required to fork out.

The last wisps of mist were evaporating from the high ridges around the Whangamomona Saddle as we wound our way down to the valley below.

At the foot of the hill, three locals leaned nonchalantly on a roadside fence. One of them held up his hand and motioned us to pull over. He shrugged himself off his post, flicked the stub of his roll-your-own into the drain and strolled over to our car.

“Ar, gidday,” he growled. “Passports?”

I handed over mine, issued a decade or so before. Whangamomona’s quartered armorial shield—photocopied sable on argent—was emblazoned on its battered cover. My passengers weren’t so fortunate. Each of them was deprived of a few dollars before we were dismissed as another car approached. For 24 hours we were “legal” residents of the Republic of Whangamomona.

The establishment of a republic is usually the result of a popular uprising in opposition to an unresponsive, autocratic political system. And so it was in “Whanga”.

The declaration of the Republic of Whangamomona on November 1, 1989, followed hard on the heels of the announcement by the chief local-government commissioner, Sir Brian Elwood, that the eastern marches of Taranaki were to become part of the Manawatu–Wanganui Region. Regional councils were to be based around watersheds, and so, as the Whangamomona and Tangarakau Rivers both drained into the Whanganui River, the die was cast.

It wasn’t that the locals had anything against the dedicated politicians and well-meaning citizens of the “Man– Wang”—now operating under the enigmatic trade name Horizons Regional Council—it was just that they weren’t Man–Wangers. Full stop. Sir Brian, with a stroke of his bureaucratic ballpoint, had unwittingly stirred up ethnic complexities in the south-west North Island reminiscent of those in south-eastern Europe.

Just over a century ago this part of the rugged Taranaki interior was opened up for pakeha settlers. By the late 1880s survey parties had explored the rolling front country on the eastern edge of the volcanic ring plain surrounding Mount Taranaki. One group, working east of Strathmore in 1889, was reported to have “decided…it would be more interesting to travel out for the Christmas holidays through the bush country to the head of the Whanganui River”. A glance at the shortest possible route on a modern map shows them to be either sadly misinformed or insane. Yet they reached the bright lights of Wanganui for the break and even returned to their surveying tasks early in the New Year.

In 1890 the tide of mapping finally reached the foot of the ridge that screened the Whangamomona valley from rapidly advancing “civilisation”. Joshua Morgan was one of the first surveyors of the valley. In March 1893, along with his chainmen, packmen and cook, he was working in the chasm of the Tangarakau Gorge when, aged only 35, he fell ill. Two of his men walked day and night to get medical aid from the nearest doctor, on the coast 50 km away, but they were too late and their efforts in any case were almost certainly futile. Morgan died before they could return, probably of peritonitis, for which little could have been done.

Morgan’s grave, right where he died on the bank of the Tangarakau River, is now a welcome but sobering stop for tourists on the winding Stratford to Taumarunui “Forgotten World Highway”. On the centennial of Morgan’s death, a moving rededication of the site drew an impressive gathering of politicians, history buffs and surveyors to the still-isolated spot shrouded in bush. Many, including me, wondered at the fortitude of the early surveyors and their families and paid silent tribute to them.

The first settlers moved into the Whangamomona valley, 65 km north-east of Stratford, in about 1895. A number of them were former gold-miners from Kumara and Dilmanstown on the South Island’s West Coast. Their legacy of independence and disdain for authority in any form whatsoever lives on to this day. In 1897–98, town sections became available and were quickly snapped up. A boarding house and a general store were soon established and a post office and other facilities followed. The original pub arrived in 1902 but burned down in 1910. The present hotel is its 1911 replacement. For nearly 60 years the town flourished as farmers, itinerant workers, railway gangers, stock buyers, shepherds, charlatans and rogues played their respective roles.

The 1989 declaration wasn’t the first hissy-fit Whangamomona threw over the behaviour of authority. Unhappy with Stratford County Council’s (SCC) tardy response to its needs, the area declared itself an autonomous local authority in 1908. The cash-strapped Whangamomona County Council then rather blundered its way through the next 50 years before re-amalgamating with SCC in 1955.

The second half of the 20th century witnessed the gradual but steadfastly resisted decline of the communities in the valley. The devastation of Taranaki’s rural heartland was epitomised by the closure of the Whanga school in 1979 and the post office in 1988, and made worse by the disastrous simultaneous slump in wool and lamb prices.

[chapter break]

Although we were early, we weren’t the first to arrive for Whangamomona’s Republic Day. Several somewhat bleary-eyed overnighters were slumped under the hotel veranda.

The Whangamomona Hotel, needless to say, has always been the centre of the town’s activity. Today it is one of the few surviving businesses in a community that once boasted a butchery, a bakery, county council offices, a school, a bank, three churches (Anglican, Presbyterian and Catholic), a combined blacksmith, garage and service station, a community hall, a general store and a railway station with a substantial siding.

Today, under the management of John and Clare Grant, the hotel benefits from the demand of city folk to experience back-country life. Weekend stays are now difficult, if not impossible, to book at short notice. In 2003, and again last year, the Grants were one of four finalists in the Best Country Hotel category of the Hospitality Association of New Zealand’s annual awards. This year, they were rewarded with the title.

I fell in with an immaculately dressed old-timer who had just arrived for the day. He was impressed by the success of the occasion. “You know it now takes months to plan?” he asked. “When it first started the whole thing was arranged on a couple of Thursday nights around the bar in the pub. But they’ve been able to keep it just like the original thing. And that’s what really matters.”

My first stay in Whangamomona, 20 or so years before, had been a revelation. In no other corner of the planet had I ever found—nor have I since—a restaurant that served “meat and seven veg” as a standard menu item. Potatoes, pumpkin, cabbage, silver beet, carrots, beans and peas—and that didn’t count the onions with the roast hogget. The gargantuan coal range in the kitchen, along the full length of one wall, heated the entire building and usually had to be approached with a well-dampened towel to protect any exposed skin from instant blistering. It’s still one of the major attractions at the hotel. “Everyone has to take a look at it,” John says.

After dinner, a session in the bar allowed the locals to assess the “outlander” in their midst. It was fully an hour before an old guy on a high stool in the corner called me over and asked if I was related to “Old Harry”. I admitted the man in question was my grandfather, and the gaffer then got serious and gave glowing descriptions of the work ethic, pedigree and illustrious progeny of the heading dog he had bought from Old Harry some time in the 1940s. The ice had been broken and the outlander became a local—or nearly so.

[chapter break]

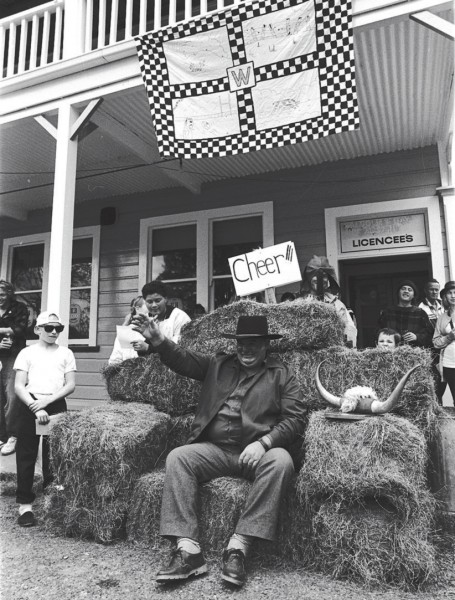

In 1989 Whangamomona swiftly installed the impressively proportioned local identity Ian Kjestrup as its inaugural president. After a decade in power, President Kjestrup withdrew with dignity to a well-earned retirement in the rural fastness of his local estates. The resulting power vacuum witnessed a bitterly fought battle for the presidency of the young republic.

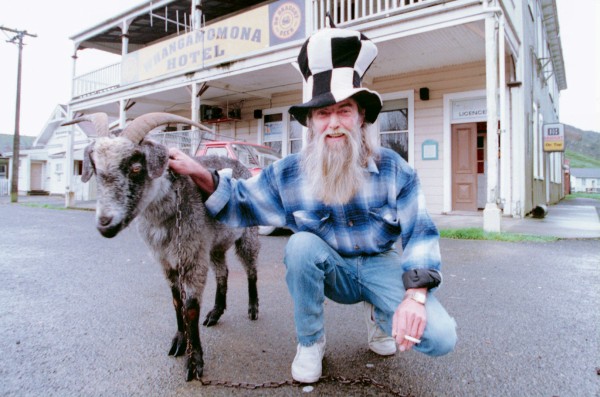

Two contenders, publican Peter “Muff” Ray and roadside goat “Billy” Hircus (a.k.a. Gumboots), were both considered by Republican spin doctor Mark Coplestone to be “down-to-earth blokes with pretty healthy beards”. Coplestone reported that “Muff’s beard probably smells better, but Billy’s is a bit more clean-cut, which should appeal to the discerning voter.”

The 1999 election resulted in a landslide for Billy. Locals relate how Muff voted several thousand times in favour of the goat to ensure his own election wasn’t forthcoming. For his part, Billy was accused of—but never charged with—eating the single vote cast for his opponent while chained to the only polling booth.

Sadly, President Billy—aged 14—died in 2001. He was buried, with full Whangamomonial state honours, in a traditional inland Taranaki wheat-sack casket on his favourite hill-top. “Several dignitaries travelled several hundred metres for the final farewell,” a distraught resident sobbed to city reporters. “It was a really big funeral—the pub was full.”

Billy’s place was taken by a relative newcomer to the republic—Tai, a standard poodle, whose owner was the hotel barman, Lew Poutu.

Tai’s presidential tenure was cut short a year or so later following an assassination attempt by an envious mastiff-cross colleague during a pig-hunting expedition.

The 2005 campaign put ex-president Kjestrup back on the hustings, along with “Murt” Kennard, the local café owner. Fresh-on-the-scene ex-Wellingtonian Bruce/Miriam Collis, whose unashamed propensity for cross-dressing raised more than a few eyebrows in the conservative rural community, was a late entry in the presidential stakes.

The campaign rhetoric had all the hallmarks of that reported during the recent US and Ukrainian elections: personal invective and slights were common, and Miriam’s questionable dress sense eventually became a major election issue.

By mid-afternoon on Election Day, the temperature was in the high 20s and the air immovable. The sweet scent of hard fern drifted from the surrounding hills. A tongue-lolling, black-and-tan huntaway corkscrewed his face delightedly through the pennyroyal in the paddock alongside the railway, then wandered away to flop, amid a mint-smelling haze, in the shade of a nearby stand of manuka.

It’s usually the dogs that most enjoy the Gut-buster Run, one of the highlights of Republic Day. It’s up the steepest ridge behind the town and is scheduled for midday or early afternoon. The time is carefully planned to ensure that competitors are able to unwind in the bar beforehand only briefly lest their hill-climbing prowess is impaired. Runners are often accompanied by several excited dogs on the well-worn sheep track through the ragwort and foxgloves to the hill-top pine tree and back. This year the field, sadly reduced in number but not in ability or enthusiasm, was led to the finish by farmer Bradley Bromich.

A battered ute wove through the multitude. It was filled to overflowing with young Black-singlets of the Kennard election team, loudly extolling the virtues of their candidate to visitors and locals alike. Polling by then was well under way, but in the republic there’s nothing like a bit of last-minute gerrymandering to keep the voters on their mettle.

Contests like gumboot-throwing, whip-cracking and horseshoeing are harmless enough; however, a few of the entertainments on Republic Day are not for the squeamish. Possum-skinning and a bizarre guess-the-number competition featuring an antique bathtub seething with eels of impressive size do not appeal to some gentlefolk. One memorable year even petrol-heads might have winced at the competition to guess the time a car engine, drained of radiator water and sump oil, would take to seize up. Presumably few entrants came even close to winning, as the time was a barely believable 35 seconds.

Early in the afternoon, two trainloads of bewildered “northern-city” rail enthusiasts were disgorged from their carriages onto the gravel ballast where the station used to be. They were politely directed along the length of Whangamomona’s main street to be efficiently relieved of their remaining small change by the rank-on-rank of craft and food stalls. Master of Ceremonies Mark Coplestone repeatedly warned the advancing tidal wave of visitors that the unusual smell they might have noticed was “fresh air” and encouraged them to “make the most of it”. They eventually returned to their carriages—less bewildered but cashless—for the journey back to the exhaust-fumed safety of the metropolis.

[chapter break]

These days, those who remain in the remote settlements between the Whanga Saddle and the Tangarakau Gorge present a unified, staunch face to the world at large. In times past their small communities—proud of their rural townships—competed with each other in sports with all the ardour and subterfuge of provincial rugby teams.

Marco (named after a surveyor’s dog killed by a large boar), Kohuratahi, Tahora and Tangarakau flowered briefly during the first part of the 20th century. Each then collapsed, becoming a mere road junction marked today only by a few ancient macrocarpa, poplar or walnut trees and old, isolated railway and public-works houses.

The chronicle of Aotuhia, 20 km south-east of Whangamomona, is typical. The lower Whangamomona River area was opened for settler farmers in 1896. For the first few years, access to Aotuhia was from the Whanganui River via a narrow bridle track. By 1914, a road that wound its way down the river from Whangamomona had been completed. This more reliable route had additional families taking up farms in the area. A few years later the settlement was established enough to have sports events in a domain, a school, a telephone exchange and post office, and even a wildcat oil well.

Difficulty of access, always a problem, was borne with resignation during the brief period of prosperity that followed WWI. In the early 1920s, gruelling times began with a slump in dairy prices as many farmers relied on the income from their small herds for ready cash. As the Depression deepened during the late 1920s and early 30s, the vicious cycle of plummeting prices and reversion of pastures began to take its toll. Most of the farmers and their families were forced to abandon their properties with what they could pack into drays. “Forfeited” was scrawled across their land deeds in New Plymouth’s departmental offices.

By 1940 only one settler remained. He was finally forced to leave his farm after floods washed out the Whangamomona road and repairs were deemed unwarranted. Thirty blocks totalling 9500 ha were given up to regrowth of manuka and fern.

From then until the 1980s, the Aotuhia valley was leased for grazing. Then a new road from Makahu was laid to service a Department of Lands and Survey redevelopment scheme, planned to form 12 farms. Although the scheme didn’t attain its original vision, Aotuhia Station is now operated as a single farming unit. The balance of the block was bestowed on the Department of Conservation (DOC) and has proved to contain a sizeable percentage of Taranaki’s fast-dwindling brown kiwi population.

Local history chronicler Derek Morris has spent years exploring the isolated valleys around Whangamomona and chatting with old settlers, many of whom have since died. One valley in particular, along with its pioneers, is the stuff of folk legend. The Marangae, as it is always known, is tucked away, like some deserted Himalayan kingdom, between razor-backed ridges.

I visited Morris one evening to find him busy with maps spread across his dining table. He waved his hand over an extensive patch of green on one of them.

“The Marangae was opened up in 1909,” he said. “It was certainly the most isolated of all the valleys round here. It was 16 km or so of hard slog just to get out to Kohuratahi. Of course today we see the Marangae as the back-of-beyond, but you have to remember that these people believed that, within a few years, they’d be surrounded by all the intended infrastructure of a viable rural community—a school, hall and store. Maybe even a dairy factory within easy reach.

“All bar one of the Marangae settlers had left by 1933, only 24 years after the blocks were balloted. They were sadly disillusioned. The last one—“Battler” Nelson—finally called it quits in 1942.”

Derek’s finger traced the meandering dotted lines of disused roads with their tunnels, cuttings, quarries and derelict footbridges on his NZMS 260 map.

“There were hundreds of kilometres of proposed roads that remained as just lines on the map and many others that were made but are now abandoned and overgrown. Over the years I’ve walked most of them and I still marvel at the number of men and man-hours that must’ve gone into forming them with just picks and shovels. And the quantity of papa they moved was just enormous. They reckon that there were dozens of road-makers’ tent camps all over the area before the First World War. The network was even surveyed to connect with Raetihi over the Whanganui River and from there north to Ohura.”

A bit later he was back on the Marangae.

“There were 12 or so farms over there, and some pretty sorry tales of families who tried and failed.

“In 1931 there was a bloke by the name of Don Morrison, who threatened a crown-lands ranger with a rifle when he arrived to collect the mortgage and rates arrears. The next day the ranger arrived back with the cop from Whanga, but Morrison was missing, his house had been burned down and all the stock and dogs shot. A couple of years later a pig hunter found his remains in a gully not far away. Morrison’s wife had disappeared a few months before. No one knows to this day whether she just walked out on him or not…but there was a rumour that she was later seen in Napier.

“Then there were the Marrs. The whole family, kids and all, were evicted from their farm and found on the roadside at dusk by a neighbour. They were 10 km from the nearest settlement and their entire possessions were in a couple of suitcases.”

As Morris folded his maps away he summed up: “I’m lucky to have been able to talk with many of these people and to share their strange combination of enthusiasm and dismay even after so many years. They were really special.”

[chapter break]

It was the social side of things that often helped residents to endure the difficulties of life in the Whangamomona valley.

In the 1920s, the Marco hockey team gained local notoriety for a spirited but bloody game against Stratford. The Taranaki Daily News was moved to print a suitable tribute, They’re Tough, Mighty Tough, in the East (with apologies to A.B. “Banjo” Paterson’s Gebung Polo Club), which began:

It was somewhere up the country, in a land of rock and scrub, That they formed an institution called the Marco Hockey Club. They were tough and wiry natives from the rugged mountainside, And the game was never thought of that at Marco wasn’t tried.

The valley also has nurtured an impressive number of individuals who have risen to sporting prominence, both nationally and locally. All Blacks Jack Sullivan, Bob Scott and Reuben Thorne; Black Fern Emma Thomas; axemen Ned Shewry, Doug McCartie and the Pittams brothers, Cliff and Leo; sawyer Sheree Taylor; champion miler Randolph Rose—all have spent at least a little time there.

The Dean Cup was presented by Athalinda Dean, the wife of the Whanga publican, in 1906. Unkind rumour has it that the cup was originally for a cricket competition but became a rugby trophy in 1907 when a suitably flat wicket couldn’t be found. “Linda’s cup” is still battled for annually on the frost-white domains of Toko and Whangamomona. This makes it one of New Zealand’s oldest surviving senior rugby trophies. The Ranfurly Shield, a mere three years the Dean’s senior, is now part of the commercialised game. The proud amateurism of the Dean Cup should, therefore, make that trophy New Zealand’s pre-eminent “dinkum-rugby” prize.

In 2003, in a spooky replay of the very first challenge 96 years earlier, Whangamomona confronted Strathmore at Yarrow Stadium in New Plymouth. It was the first game since the 1907 match to be played outside the Eastern Districts. Strathmore won 17–16. In 2004 Toko won, so the Dean Cup is shared around a bit.

Rugby and hockey aren’t the only competitive sports played in these parts. On the roadside bank opposite the main door of the Whangamomona Hotel is a decaying cross-section from a forest giant, nailed upright among the cocksfoot seed heads and manuka. Painted like a dartboard from Hell, it’s a target for axe-throwers who compete from the pub door. No one has yet been reported injured or killed while competing.

The recreational activities of rural communities like Whanga are seldom far removed from everyday life. Dogtrialling, shearing, chopping and sawing competitions test abilities and talents honed by competitors’ occupations.

Most conversation gets round to dogs, sheep or axes once politics, rugby and the weather have been disposed of.

Dog-trialling is a family affair. Three generations of Murphys (Bill and Gus; Bernie, Gary and Des; Steve and Dan) have dominated the scene in Taranaki for decades. They have, though, been equalled and occasionally surpassed by other locals, such as Denny McAloon and Don Law. In the 2005 club champs, 14-year-old Lance Downs and his bitch, Tee, from Aotuhia Station, created something of a sensation by qualifying for the run-offs, held at the Taranaki Centre. There, the pair gained a creditable third place in the long head. Old hands predict a bright future for the young trialist.

Neither red nor fallow deer have spread into the area in significant numbers, so wild pigs—Captain Cookers have for years provided the main blood sport. Brought in by Maori, pigs were already well-established when the first pakeha arrived. By the 1920s they were so numerous they often rooted up hectares of hard-won pasture in a matter of days. They also killed and ate a large percentage of each spring’s crop of newborn lambs. Back then weekend tallies of more than 60 animals weren’t uncommon. Pig-hunting was a matter of survival for many farmers.

These days pigs aren’t that common, but madmen—like my son and his friends—still scour the ridges and gullies accompanied by piratical packs of tusk-scarred dogs. They are perpetually searching for the “Big Red (or Black) Razorback Boar”, claimed by legend to have dwelt for years in the depths of any one of the distant valleys.

I must say that I appreciate the occasional bloody hindquarter—its origins still obvious from adhering leaves and remnant bristles—that appears in my fridge. It makes a most acceptable alternative to a plastic-wrapped, production-line joint from the supermarket chiller.

Another local legend, one of New Zealand’s most acclaimed axemen, hailed from Kohuratahi, a few kilometres north of Whangamomona. John Edward (Ned) Shewry was a world champion around the time of WWI. His prowess in demolishing gigantic blocks of kahikatea or poplar 60 cm in diameter won him deserved international fame. Shewry possessed axe-wielding skills that are still held in considerable awe by modern practitioners. Apocryphal stories of his exploits abound. As one elderly, but still dangerous-looking, ex-chopper related:

“Yup, ol’ Ned use’ t’ dehorn his yearlin’s with a naxe, so they say. Stood over the race, he did—one foot on each side—and never missed a beat. Just lopped them off, he did. Bloody marvellous t’ watch, it was! Just bloody marvellous!”

Ned served in the New Zealand Cyclist Corps during the war and was awarded the Military Medal for “disregard for danger and devotion to duty and comrades in distress” at Marfaux, in France. Ned, though, reckoned he got it “because I kept the cookhouse supplied with kindlin’ wood!”

In his later years, having destroyed many trees during his long life, he became a dedicated supporter of Taranaki’s Pukeiti Rhododendron Trust and, on his death, left it his substantial estate.

[chapter break]

In the second half of the 1920s, the township of Tangarakau was for a short time home to as many as 1200 or more. As well as several stores it boasted a bakery, drapery, hairdresser-cum-tobacconist, fruiterer, library, doctor, boarding-house, sports fields, maternity home and school, plus all the other trappings of a self-sufficient, isolated Kiwi community. With three discrete residential areas for, respectively, single men, married couples with children and married couples without children—the last of these being known as the seedless-raisin section—it was established in 1925. It was to be the base for railway construction in the area, including the driving of six of the 24 tunnels needed to link Stratford with the Main Trunk Line near Taumarunui. The line was begun in 1901 but completed only in 1932. After that the rail gangs and their families moved on, many to other public-works projects. For some time the town also housed construction workers erecting the pylons for the electrical transmission line from Arapuni power station to Stratford.

The arrival of the railway from Stratford in 1914 overcame a nearly insurmountable problem for early road engineers. It was almost impossible to find accessible hard rock for surfacing in the soft tertiary mudstones of the valleys. Initially, many roads were of corduroy construction—built with split-timber slabs laid transversely—or made with fascines of manuka, which had to be regularly replaced as they rotted and sank into the clinging mud. After the winter, the cut-up road surfaces had to be levelled before they dried and hardened into concrete-like waves and troughs for the summer.

The lack of road metal was partially overcome using a technique devised in Wairarapa in about 1894. There, on the notoriously unstable Weber to Alfredton road, soft papa mudstone was fired in kilns to produce brick suitable for surfacing. The first “papa burning” trials at Whangamomona were made in 1898 by William Nathan, the resident Public Works Department overseer.

Small kilns were built on the side of the road, and larger “face kilns” in cavities blasted in the papa hillsides. They were of primitive construction, alternate layers of timber and clay being piled up and then covered with earth. Firing took several days, after which the brick-like product was broken up and spread over the road. Many of the area’s “red-brick roads” are now covered with more conventional gravel or asphalt, but fragments of the older surfacing may still be seen on Marco Road and outside the Whangamomona cemetery.

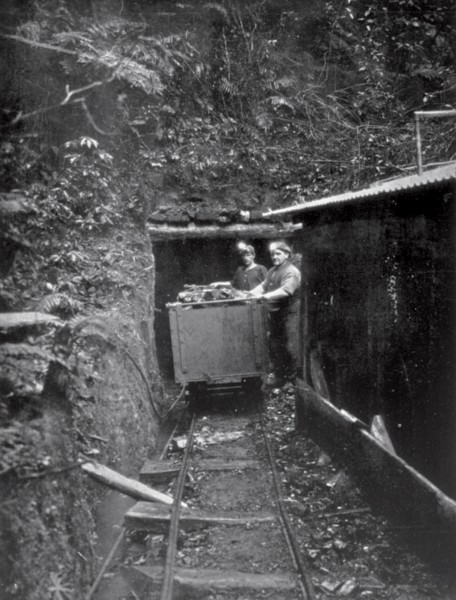

Black, too, is a signature colour of the area. The sub-bituminous coal deposits in the Tangarakau Gorge are part of several extensive Miocene-age fields that run from the Mokau River and south Waikato to Ohura and Tangarakau. Beginning in the 1920s, outcrops in the gorge were mined in a small way, with the coal being brought across the river by aerial ropeway to roadside bins. Later, Egmont Collieries was formed and transported the coal via a bush tramway alongside the river to Tangarakau township, where it was loaded into rail wagons. The mine closed in 1934.

The company also began mining at Tatu, on the Ohura side of the gorge, but in 1940 the government-owned State Coal took over the operation. The Tatu mine eventually closed in 1971, mainly because of the national decline in demand for coal as other Taranaki black gold—oil and gas—became increasingly available. The 1979 international oil crisis reactivated interest in the area’s coal reserves, and the possibility of open-cast extraction remains, given the imminent demise of the Maui gas field.

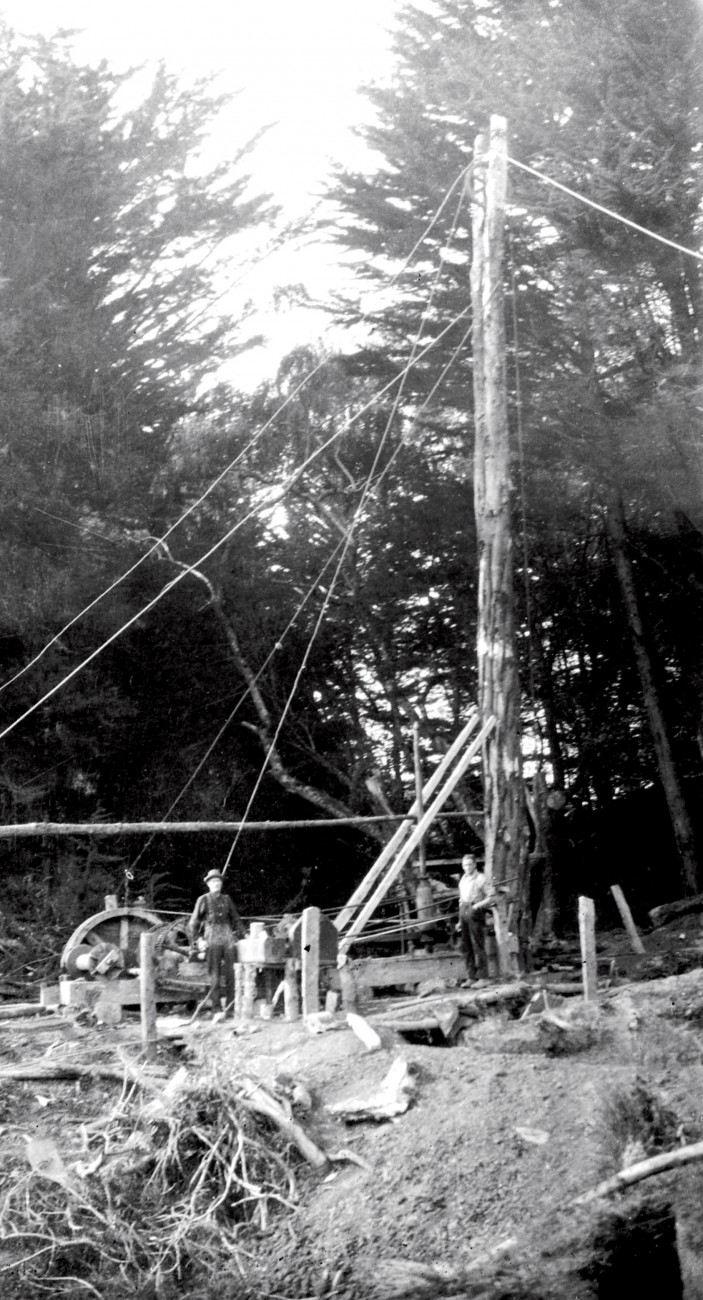

In order to keep up in the oil-exploration stakes, Whangamomona joined in Taranaki’s early-20th-century obsession with petroleum. In the late 1920s, several farmers on Prospect Road began drilling without the required Mines Department authority. After being taken to task they eventually capitulated and formed the impressively named New Zealand Petroleum Syndicate. Although the drilling rig consisted only of a macrocarpa trunk and several ingeniously used car parts, the syndicate’s two wells are reputed to have reached around 300 m before being abandoned as both the group’s enthusiasm and its capital ran out.

[chapter break]

At around 2 p.m. on Republic Day 2005, the result of the presidential election was announced and Murt the café owner was installed as the fourth president of the Republic of Whangamomona. The result was greeted with a brief cheer from the crowd and a short speech by the new president. “That’s unusual,” someone nearby commented. “This one can actually talk.”

The sun was lowering in the west but the asphalt was still liquid when we decided to leave the republic. A reasonably easy drive of 90 minutes and 100 km would have us back in New Plymouth. But we did spare a thought for those travellers of a century before who, with a lot of luck and a really good run, might have made 15 to 20 km in that time.

A couple of weeks after Republic Day I re-acquainted myself with the valleys beyond the township.

On the outskirts of Whangamomona the republican administration had, in their usual laconic manner, placed a safe-driving slogan on the rear of the “Welcome to Whanga” hoarding—“Please Drive With Your Eyes Open”.

To the north lay an ocean of grassland ridges surmounted by steep-cliffed, bush-clad caps, like crusader castles in the Levant. Blame them on land-clearing practices and geomorphology. Fourteen mixed dairy-and-beef farms were made available around Marco and Kohuratahi under the Discharged Soldiers Settlement Act after WWI, beginning a process of transformation of the hill country that reached its peak with the introduction of aerial top-dressing after WWII. Yet remoteness and fluctuations in beef and wool prices have often made farming here a tenuous occupation.

David Walter, a farmer from Douglas (about 25 km along the road to Whangamomona from Stratford), a long-time local authority politician and now chairman of Taranaki Regional Council, has been analysing the changing farming, population and social patterns of the area for the last 30 years.

“Over the past four or five years farmers in the area have had the best mutton and beef prices since the 1960s and they’ve been able to catch up with long-neglected maintenance—and even upgrade their ageing cars. Confidence has returned to the hill country, but the number of farm units has shrunk dramatically as amalgamation of farms has increased.” With a wry grin he continues: “And gone are the prophets of doom of the 1980s and 90s, who saw pastoral farming as a sunset industry. Gone, too, are those who preached widespread planting of pine trees. It’s now the beleaguered forestry industry that looks like dipping below the horizon.

“The 70 per cent population exodus from the old Whangamomona county during the 1960s and 70s has turned around. It’s got a long way to go yet, but most of the spare houses around the valleys are now occupied by contractors and farm hands whose labour is again keenly sought. Tourism, and the profile given to the area by Republic Day and the Forgotten World Highway, New Zealand’s first heritage trail, is beginning to pay off.” Walter believes that this isolated bit of country has begun the new millennium with an air of optimism unparalleled since the wool boom of the 1950s.

[chapter break]

I passed through Marco, home to one of the two remaining schools in the area, and continued on to Kohuratahi, now with little more than a public hall and a small roadside war memorial. A sobering 41 of the district’s 130 serving youths were killed in WWI, most of

them in the mud of France and Flanders in 1917 and 1918. That’s nearly double the 16 per cent national average. Then it was on to the fourth and final saddle, Tahora, before the descent into the watershed of the Tangarakau.

The road here winds along the spine of the ridge past Kaieto Café, with its stupendous views east to the central North Island volcanoes—Ruapehu, Ngauruhoe and Tongariro—then round to the west and the legendary outcast, Mount Taranaki. Half-a-dozen harriers flew reconnaissance patrols on the updrafts along the slopes of the ridge, and the croaking of bell frogs—all too uncommon these days—rose with the late-morning thermals from a stock pond in the valley far below.

A fifth saddle, Moki—once, by repute, the worst of them all—is now pierced by a Gothic-arched tunnel completed in 1936, but the old, evil road survives as a pleasant walking track through Tahora Scenic Reserve.

Just before the highway enters among the towering crags of the Tangarakau Gorge, the Moki road veers off towards Mount Damper and, finally, to the coast at Tongaporutu. It was only in 1984 that the last stretch of this road was completed, allowing a 250 km round-trip through Stratford. As if to prove that nothing much is ever new, the old Tihi Manuka trail passed near here, giving coastal Tainui access to the upper Whanganui River and the Taupo basin beyond.

In a programme similar to that run at Aotuhia, the Department of Lands and Survey purchased the struggling station at Mount Damper in the 1960s and developed it for sale a couple of decades later.

It was from the extensive upland tawa–kamahi forests around here that the last of Taranaki’s kokako (Callaeas cinerea) were captured and transferred to captive-breeding facilities a few years ago. Only 20 years before, a couple of friends and I had been privileged to hear the heart-stopping dawn chimes of free-range “bluegills” echoing along the ridges near Tahora. Those lonely calls could well have been the death song of the local kokako, as their population plummeted to a mere half-dozen birds by the 1990s. It was hoped that the transfer would keep the Taranaki birds’ characteristics circulating in the wider kokako gene pool and provide some variation to shore up the perilously small populations in other areas. Sadly, the staunch “Valley” birds have been reduced to a single male, Tamanui. During the 2004–05 season he finally condescended to mate with a Waikato female to produce two chicks. That has got to be carrying independence and disdain just a bit too close to extinction.

Some even older Tahora residents have already travelled the path to oblivion, although they are still occasionally found imprisoned in spheres of hardened mudstone. The immense Miocene crab, Tumidocarcinus giganteus, roamed the deep oceans of the continental shelf here between 5 and 15 million years ago. The males have huge right-side chelae (claws), often larger than their bodies. One of the biggest claws recorded was a massive 200 by 110 mm—the size of a large human hand.

I was still at secondary school and helping a neighbour to milk his cows when I realised that the weight being used on the milking cups to machine-strip the herd was a large fossil crab, still mostly protected by a skin of mudstone. Bruce recalled that he had found it while working in a road gang at Tahora during the Depression. He readily agreed to exchange it for a rock from the nearby creek and I became its proud new owner. In the absence of any available literature at the time, I sent the director of the old Dominion Museum in Wellington, Dick Dell, a drawing of the beast, which he soon identified as a male Tumidocarcinus. Although over the years I’ve found a few leg fragments embedded in north Taranaki cliff faces, no further specimens in such good condition have come my way.

For the first few hundred metres, the 20-minute walk to Mount Damper Falls follows a clay farm track alongside the sluggish, Kahlua-coloured stream. Tiger beetles buzzed before me, and a few long-tailed cuckoos and their whitehead hosts called from the bush beside the creek before its descent to the falls. Increasing numbers of tourists in recent years have meant that DOC now has a viewing platform above the breath-taking chasm below the falls, but when I first visited the spot, nearly 30 years ago, I could see the waterfall only by hooking an arm around a sturdy tree and leaning out over the abyss.

[chapter break]

Diplomatically, it was necessary for me to make a courtesy call on the Kennards’ café and see how the new president was handling the pressures of office. Murt was uncharacteristically subdued. “It was OK till the full initiation last night,” he muttered. “Ex-President Kjestrup turned up after the pub closed with the bottle of ‘initiation whisky’ and took off the cap. It was pretty late this morning when the ceremony finished.”

“And I had to get our B & B guests sorted by eight this morning,” chipped in Marg, the first lady. “So it’s going to be a looong day.”

We talked a bit about Republic Day.

“They reckon there were 5000 people through the village,” enthused Marg. “A thousand came on the trains. I was cooking Whanga Burgers, sausages and other food all day. And the school and other stalls were also run off their feet. None of us could keep up with drinks and I was just handing out glasses of water later in the afternoon, when it really got warm.”

Things were a bit quieter now. A couple of elderly through-travellers were lunching in front of the café, and a half-dozen twenty-somethings lounged at plastic tables outside the pub over the road before jumping into their cars and driving off towards Stratford.

With increasing tourist traffic of this sort, locals are slowly becoming accustomed to cameras of one sort or another being used in their midst. In one of its earliest forays into Taranaki, the New Zealand film industry came to Whangamomona at about the same time as Vincent Ward was shooting his bleak and sinister Vigil in the Uruti valley, a few watersheds to the west. Makutu on Mrs Jones was a 25 minute “short” filmed here in 1983, for which the buildings got a much-needed spruce-up with a quick coat of paint. Makutu, based on a short story by Witi Ihimaera, was directed by Larry Parr and starred Annie Whittle as Mrs Jones and silver-locked Taranaki kaumatua Sonny Waru as Mr Hohepa, the tohunga.

A bush ballad, composed by shearers following an incident in a shearing shed at Mt Damper Station in 1948, was popularised when it was performed at Tahora Folk Festival 30 years later. It tells of an exasperated novice shearer who “spins out” and kills a sheep with a blow from his hand-piece just as the boss arrives on the scene.

It was up the Mangapapa in the Amalgamated shed

Where a chap named Tommy Marshall went completely off his head.

He was shearing as beginners do, with hands and feet and teeth Making a tough go of it amongst the froth and heat.

Up the Mangapapa where it rains all day

Up the Mangapapa amongst the fern and the clay.

The ballad was later recorded by local folk-song guru Mike Harding on his 1998 album Past to Present and is a truly indigenous piece of Taranaki folk music.

In songs such as this it’s all too easy to romanticise the “carefree” existence of an earlier rural New Zealand. Even the success of such celebrations as Republic Day reinforces this notion.

For today’s urbanites, a weekend without access to supermarkets, sports goods and shoe stores and with only faltering cellphone coverage is marginally survivable—but only if a return to the “real world” is programmed for late Sunday. Yet thousands live full and contented lives in rural communities around New Zealand, and it is really these and their generations of resilient predecessors that Whangamomona Republic Day celebrates in grand manner every couple of years.