Waitaki: water of tears, river of power

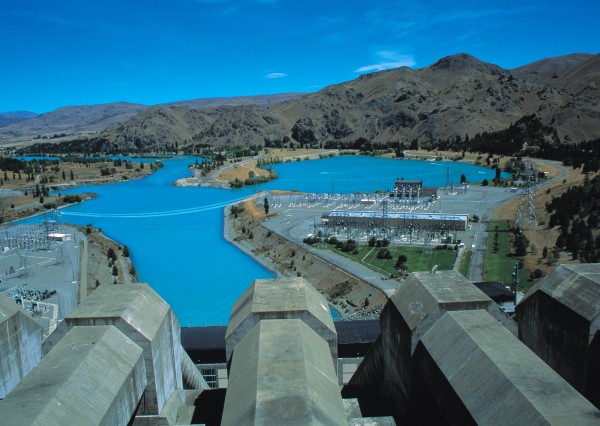

In an age when rivers are managed to satisfy the competing demands of dozens of users, the raw power of a mighty river such as the Waitaki is rarely seen. Draining the central mountains of the South Island from Mt Cook National Park south to the Lindis Pass, the waters of the Waitaki—”water of tears”—now churn the turbines of a bevy of power stations before being siphoned off to irrigate dry plains closer to the coast. Here, 1000 cubic metres of water a second thunder across the spillway of Lake Benmore hydro station.

When i arrived in the hydro town of Twizel in 1982 I knew little about the river that was the reason for the town’s existence. I’d seen it only once before, glimpsed through the fogged window of a bus while travelling between Christchurch and Dunedin. At the time, I thought it looked like all the other rivers we had crossed on the journey south: just another braided waterway meandering its way down a shingle floodplain, lined with willows and spanned by the ubiquitous long, narrow, bumpy bridge.

But during seven years of working as a fisheries biologist around, in and sometimes under its milky blue waters, I came to appreciate how central those waters are to many lives, and realised that the Waitaki was more than just water.

Early Maori fished and hunted on the river they named “water of tears.” The name refers to tears shed by Tane, god of the forest, for Tangaroa, god of the sea. (“Waitaki” is the southern variant of “Waitangi.”) The waters of the river were also referred to as Wai-para-hoanga, or water of grinding-stone dirt, a reference to the high concentrations of glacial silt suspended in the water and the reason for the river’s distinctive milky hue.

When European settlers arrived they started farming its wide plains. Engineers constructed bridges and then dams and irrigation schemes, diverting channels and filling hydro lakes.

Today, anglers value the water for its superb trout and salmon fisheries, while boaties and campers enjoy its spectacular lakes and dramatic scenery. Conservationists also hold the Waitaki in high regard because its wetlands are the home of the world’s rarest wading bird, the black stilt.

All these groups have a significant stake in the Waitaki. And while it means different things to different people, all are united by a passion for the river.

If you want to find out what happened on the Waitaki River before European settlers arrived in the 1840s, you can read the excellent accounts compiled by historian James Herries Beattie—or you can ask Kelly Davis. The solidly built Davis is a descendant of renowned chief Rawiri Te Maire, who roamed the Waitaki valley 130 years ago, and he has the river in his blood.

When Davis talks about the Waitaki, he tells of traditional native fisheries, expeditions into the headwaters to hunt for moa, and the spiritual significance of the water. “It was a key fishery for Ngati Mamoe, Waitaha and more recently Ngai Tahu,” Davis says. “Tuna [longfinned eels], inanga, koaro, kokopu [three types of galaxiid], kanakana [lamprey], paraki [smelt] and aua [yellow-eyed mullet] were all taken, but tuna was the most important species.

“I walked many of these makatea [trails] with my father when I was young, and they’re dotted with nohoanga [camp sites],” Davis recalls. “The hunting parties collected and processed food at these sites or stayed overnight on the way to tauranga waka [food-gathering places].”

More than 300 nohoanga have been found on the Waitaki River valley—a reflection, says Davis, of both its significance as a food source and as a convenient pathway through a landscape largely covered with scrub and bush to moa-hunting grounds in central Otago and pounamu rivers in Westland. Hunting parties could float their booty downriver in a quickly constructed canoe made from raupo or flax stalks.

Equally important to Maori is the river’s spiritual significance. Its catchment includes the country’s highest mountain, Aoraki (Mt Cook), regarded by Maori as an ancestor of lofty mana.

The Waitaki was the site of Hipa Te Maiharoa’s epic land protest. A powerful religious leader and prophet, Te Maiharoa established a settlement at Te Ao Marama (now named Omarama) in the headwaters of the Waitaki in 1877. He claimed that this inland area had not been sold to the Crown, and belonged to iwi.

Te Maiharoa and about 150 protesters, including Te Maire, occupied the site for two years before Minister of Native Affairs John Sheehan gave the order for police to evict the protesters. When Inspector Andrew Thompson and 12 constables arrived to enforce the eviction order the protesters refused to leave.

Te Maire was arrested and tempers flared. A protester tried to shoot Thompson but was restrained by Te Maiharoa—avoiding bloodshed and possibly the start of land wars in Te Wai Pounamu (the South Island). Two days later the protest ended peacefully and Te Maiharoa set out for a reserve at Korotuaheka (Waitaki mouth), where he died in 1885.

The injustices suffered by Maori on the Waitaki were recounted by Te Maire when he appeared before a Royal Commission of Inquiry in 1891. “All the mahinga kai are taken by Pakeha,” the old chief lamented. “The Waitaki is not available to us, owing to it being stocked with trout. Some of us were nearly put in jail for catching weka on the runs because station owners wanted them for game, but afterwards the weka were killed by poison.”

Davis says Maori values and taonga have been further eroded since the river was developed for hydro power. Longfinned eels are gradually dying out in the upper catchment because dams impede upstream migration of juveniles. Nohoanga and makatea have been inundated by hydro lakes.

The impact of hydro development on traditional Maori taonga was ignored, says Davis, until the Resource Management and Ngai Tahu Settlement acts “put Maori back onto the playing field.” Now Ngai Tahu is negotiating with Meridian Energy, which owns all eight power stations on the Waitaki River system, to resolve the issue of customary Maori fishing rights.

[Chapter break]

The first europeans on the Waitaki River came to the area 33 years before Te Maiharoa’s protest. Edward Shortland, a doctor, guided by the son of a sick Maori he had attended, travelled north from the whaling settlement at Moeraki, reaching the Waitaki River near Papakaio in January 1844. Shortland noted that “they crossed the plains walking without trouble, for the soil was stoney and barren, producing nothing that grew higher than the knee.” The explorers headed inland to Georgetown, where a group of Maori ferried them across the flooded river on small raupo canoes. Shortland wrote in his diary that the Waitaki was “furiously rapid and a dirty white colour.” The Maori’s leader, Huruhuru, explained the river’s source and the route over the Lindis Pass to Hawea and on to the West Coast. Huruhuru drew a sketch of this route for Shortland, which for years remained the only official map of inland Otago.

Walter Mantell was the next notable European visitor, arriving in 1852 to survey the Maori reserves for the Crown. Mantell went further inland to Kurow and discovered Maori rock drawings near Duntroon. He was later appointed commissioner of Crown lands for Otago. It became his responsibility to oversee the settlement of farmers on land purchased from Maori by the New Zealand Land Company.

Seven years after Hugh Robison built a sod but near Oamaru Creek, in 1853, and started establishing the first station in the area, almost the whole Waitaki valley had been settled. Land was allotted on a first-come, first-served basis, although the ownership of one station was decided in a novel way when two pioneers, Hugh Fraser and Alexander McMurdo, both fancied the same property. The pair agreed to settle the matter by racing their horses to the nearest matagouri bush. McMurdo won the race, and with it the right to lease the 128,000 ha that became Benmore Station. Fraser had to settle for second best, Ben Ohau Station, on the other side of the Ohau River.

The Waitaki valley boomed on the back of high wool prices in Britain and the unexpected bonus of gold discovered in the Maerewhenua River. With the gold came bushrangers, who terrorised and robbed miners. The notorious Kelly Gang developed a fearsome reputation, holding up the Duntroon Hotel and Great Western Hotel at Kurow Creek in the 1860s. At the Great Western, the audacious Kelly held the entire pub at gunpoint while ordering the cook to prepare his gang a meal.

By 1866, the nearest town, Oamaru had become a thriving service centre of 5000, and in 1876 a road-rail bridge was constructed across the Waitaki River near Glenavy.

The rate of geographical change was astonishing. Farmers replaced native grasslands and trees with pasture, and introduced plants swept through the open, shingle riverbed like wildfire. Large stations were divided into smaller ones as the demand for land in the Waitaki valley escalated. Within three decades Europeans changed the face of the valley dramatically.

By 1925, the South Island needed more electricity to sustain an expanding population. Power stations at Coleridge, Waipori and Monowai were reaching their limits, and hydro engineers charged with finding new dam sites turned their attention to the Waitaki River. Its central location and large flow made it ideal for hydro development, and three years later work started on the 36 m-high Waitaki Dam, near Kurow.

Conditions for the 1230 workers on the dam site were brutal. Using picks, shovels and wheelbarrows, they battled freezing cold winds and icy water in the winter and searing heat in the summer. The site was also notoriously unsafe, and by the time the project was finished, 11 workers had been killed and 1864 compensation payments made for injuries.

In his private memoirs, one employee, Bruce Painter, recalled the horror of witnessing three of these fatalities while working on the dam. One labourer had both legs severed by a runaway concrete trolley, another fell and was impaled on steel reinforcing and a third slipped off a scaffold and drowned in the river. Such fatalities were regarded as an inevitable part of working on a construction site during the 1930s, says Painter. He recalled that blistered and bloodied hands were a common sight, and not considered worthy of complaint. Workers knew they were fortunate to have a job and accommodation during the Depression.

The Waitaki Dam project provided New Zealanders with more than just electricity. It was the birthplace of ground-breaking social policies that included free healthcare and hospitals. These policies had been embraced by an idealistic young doctor, David McMillan, who looked after the Waitaki Dam workforce for five years. When McMillan left Kurow to become a member of the first Labour government in 1935, he played a key role in devising the Social Security act. Political observers noted that the scheme had many similarities to the Waitaki Hydro Medical Association’s healthcare system.

McMillan was joined in the Labour government by Arnold Nordmeyer, who had also been associated with many of the dam workers while he was minister at the nearby Kurow Presbyterian church. Nordmeyer became better known as a minister of another kind, producing the notorious Black Budget as finance minister of the second Labour government in 1957.

As New Zealand recovered from the Depression, and the economy starting growing, hydro development continued on the Waitaki River. A 25-megawatt power station at Tekapo was completed in 1951, and seven years later work started on the Benmore Dam. The 1550-strong work force completed the massive 110 m-high dam in 1965. The Aviemore Dam was constructed between Waitaki and Benmore in 1968, completing a series of three dams and hydro lakes on the lower river.

Development of the upper catchment occurred between 1970 and 1985, when water from lakes Tekapo, Pukaki and Ohau was diverted through a 57 km network of canals to a series of four low-head dams. The level of Lake Pukaki was raised 37 m, effectively doubling its storage capacity, lake outflows were controlled and a new hydro lake, Ruataniwha, was formed.

At the time, the upper Waitaki development scheme was the largest of its kind in the world. Workers operating huge machines toiled round the clock, shifting mountains of earth, pouring thousands of tonnes of concrete, fabricating steel and installing complex electrical systems.

Nearby Twizel was like a giant ant colony, with hundreds of workers continually moving back and forth to the site.

Overseeing this multi-million dollar task was project engineer Max Smith, who, at the time, was arguably one of the most powerful men in the country. A larger-thanlife personality who knew every one of his Ministry of Works staff by their first name, Smith was affectionately known around Twizel as “God.”

In addition to its magnitude, Smith says that a remarkable feature of the upper Waitaki development was that it proceeded without any major protests from environmentalists. Ironically, the only real conflicts occurred between Smith and the two developmental agencies, the Ministry of Works (MOW) and the New Zealand Electricity Department (NZED). Determined to leave a legacy of more than just dams and canals behind him, Smith used the engineer’s equivalent of poetic licence to construct an Olympic-standard rowing course on Lake Ruataniwha. He also spoke out against the MOWs plan to abandon Twizel when the project was completed.

“They weren’t very happy about the rowing course, but it didn’t require any more work—we just pushed a bit of dirt around here and there. I couldn’t see the point in dismantling Twizel either. It had better facilities than most other rural towns its size, so I spoke out.”

A power struggle developed between Smith and MOW officials in Wellington. There were rumours that the bean counters were unhappy with Smith’s autocratic, yet pragmatic and highly effective, style, and that his days as project engineer were numbered.

The pressure was too much for Smith, and after 39 years of building dams he opted for early retirement. However, Smith had the last laugh. Twizel is now a thriving holiday township, and NZED’s successor, the Electricity Corporation of New Zealand (ECNZ), is a sponsor of the country’s major rowing events—including those at Ruataniwha. “I have a bit of a chuckle when I think about that. They didn’t want a bean of Twizel or the rowing course back then.”

Now living on his North Canterbury farm, Smith makes a point of attending at least one rowing regatta at Lake Ruataniwha each season. When he drives through the Mackenzie Basin and views the dams, canals and power stations that he helped build, he reckons “it didn’t work out too badly.”

[Chapter break]

After 50 years of endeavour, the Waitaki system now has eight power stations with a generating capacity of 1758 mW, enough to supply almost a third of New Zealand’s electricity needs. The retail value of the power generated on the Waitaki is estimated to be $700 million per annum. But not everyone is impressed with what the Waitaki has become. In these more environmentally enlightened times, many are concerned about the loss of open, braided river habitat that is critical for black stilts, wrybill plovers and black-fronted terns. These rare native birds were already under threat from introduced predators when large areas of their habitat were either flooded by hydro lakes or left high and dry by the canal system. Black stilts were the worst affected because their breeding and nesting is confined to the upper Waitaki. Numbers plummeted and the species was on the verge of extinction when the Department of Conservation (DOC) launched a successful recovery programme in 1981.

Manager of the programme Dave Murray admits it is an expensive and labour-intensive task, but says it has paid dividends. The chance of a black-stilt egg hatching and developing into an adult has been increased from one to 30 per cent. Despite that improvement, numbers of pure-black adults (as opposed to the more common pied form) in the wild have increased from a perilously low 30 in 1981 to a still perilously low 40 in 1998/99.

“The situation is still critical,” says Murray, “but with the wild and captive management techniques now developed there is definitely light at the end of the tunnel.”

Part of the recovery programme is the removal of invasive introduced vegetation from rivers in the upper Waitaki—vegetation which has smothered many open shingle riverbeds in the catchment, destroying habitat suitable for black stilts, wrybill plovers and black-fronted terns. Project River Recovery has seen thousands of willow trees removed and widespread spraying of lupins, gorse and broom and other weeds in the Tekapo, Ahuriri and Pukaki Rivers. Artificial wetlands have also been created, and Murray says the birds have responded by returning to these areas to feed and nest.

While the project has enhanced habitat for wading birds, it is not without critics. Anglers are concerned that the removal of willows has degraded trout habitat, tourist operators lament the loss of the spectacular Russell lupins and local residents are worried that spraying herbicides over rivers will harm water quality.

Along with its impact on wading birds, the Waitaki hydro scheme has taken a toll on migratory fish species including salmon and eels. When the Waitaki Dam was completed, salmon were prevented from reaching spawning grounds in the upper catchment. For the next five years (the maximum age reached by salmon in New Zealand) thousands of fish accumulated below the dam, trying to migrate upstream. Denied access to the upper catchment, they were forced to spawn in the Hakataramea River, the only suitable tributary downstream of the dam, and in side braids of the lower river. Although there is no accurate historic data, fisheries scientists estimate that salmon spawning runs decreased from around 100,000 to around 10,000-20,000 fish per year.

The movement of native fish species, most of which are diadromous (they migrate between freshwater and the sea at some stage of their life history), has also been restricted by dams. While species such as common and upland bullies have adapted by forming land-locked populations above the dams, longfinned eel numbers have declined in the upper catchment.

Attempts to help migrating fish surmount the dams have had mixed success. A fish ladder for salmon constructed on the Waitaki Dam was a failure, while the effectiveness of juvenile eel passes recently installed on the Waitaki and Aviemore Dams is still being assessed. One of the few successful innovations has been a manmade spawning race at the base of Aviemore Dam. The one-kilometre-long race is the only spawning tributary for brown and rainbow trout in Lake Waitaki, and is used by 200-400 fish each season.

In addition to these long-term impacts, hydroelectricity generation has delivered some one-off hits on the environment. Silt loadings were elevated in the lower river while dams were being constructed, smothering bottom-dwelling stream invertebrates that are an essential source of food for fish.

Perhaps the single most catastrophic incident occurred on April 3, 1992, when an ECNZ blunder resulted in the Waitaki’s flow being reduced to a 35 cumec trickle. Thousands of trout, juvenile salmon and native fishes were stranded and died before ECNZ operators realised their mistake and hurriedly increased flows. Red-faced executives agreed to compensate for the mishap by releasing 100,000 salmon smolts into the Waitaki from 1993 to 1997.

Despite the complaints of jetboaters, kayakers and anglers about the loss of prime recreational waters as a result of the Waitaki scheme, the development has in some ways enhanced the catchment’s recreational values. The hydro lakes are a big attraction, and roads formed during development have improved access throughout the upper catchment. In addition, the dams have stabilised flows, reducing the incidence of severe flooding and erosion in the lower river. The average annual flood in the Waitaki is now only 800 cumecs, just over two times the normal flow of 364 cumecs. This makes the Waitaki much tamer than most New Zealand rivers, which have a mean annual flood of around 20 times the mean flow.

“Sure, things have been changed around, but not all the changes have been detrimental—it’s just different,” says Central South Island Fish and Game Council field officer Graeme Hughes. “The lakes are definitely more popular than the sections of river they replaced—campers and boaties think so, anyway. They support some pretty good trout stocks as well.”

Opinions on the impact of any hydro development span the whole gamut from praise to vilification, but Hughes’ assessment is probably close to the mark.

[Chapter break]

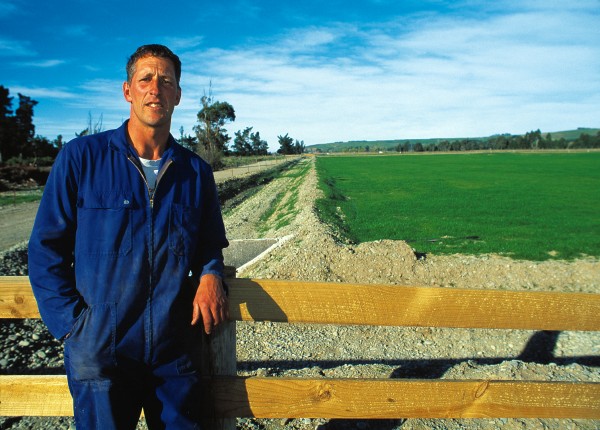

Duntroon farmer Sid Hurst has always known what water could do for farmers on the Waitaki plains. As a young lad he helped his father siphon water illegally out of the Oamaru Borough race to wild-flood paddocks. The response was dramatic. Irrigated areas turned green and flourished, creating a stark contrast with the arid brown of surrounding paddocks.

“The race had more than enough water for a town the size of Oamaru, so we used to take a bit now and then. It made me realise that water could completely change farming on the Waitaki plains,” Hurst recalls. Hurst decided to try to convince his neighbours that what the area needed was an irrigation scheme. After some initial hesitancy on the part of the more conservative farmers, agreement was finally reached and construction started in November 1970.

The first water flowed to farmers in September 1974, and eight years later the scheme was completed, at a cost of $8.98 million. Now 200 km of raceways and 12 km of pipes deliver a maximum of 17 cumecs of water to 16,000 ha of land. In this drought-prone province with a mean annual rainfall of just 480 mm, dry, unproductive paddocks have been transformed into some of the most productive and valuable farmland in the South Island.

“The big advantage on the Waitaki is the reliability of the water—farmers can maintain high stocking rates with confidence, and this is why dairying has taken over,” says farm consultant Richard Green. “Irrigation lifts the carrying capacity of the land from around five stock units per hectare to 15-20.”

Land once dominated by pastoral and cropping farmers has been largely converted into dairy farms that now cover 12,000 of the 16,000 hectares of land watered by the Lower Waitaki Irrigation Scheme. A core of sheep and cropping farmers have remained on the Waitaki, but Green says many have sold out to offers they simply couldn’t refuse. Dairy farmers have transported around 40,000 cows into the Waitaki Valley in the past 16 years.

For those farmers who have stayed with cropping, sometimes because residual DDT levels in the soil exceed the minimum acceptable for dairying, the benefits of irrigation are also substantial. Green says cereal crops on irrigated land yield about 30 per cent more than on dry land. Farmers can also resow winter green feed crops after harvesting, knowing they will grow quickly in the autumn.

Now there is a possibility that another major irrigation scheme covering a further 16,000 ha will be developed. A farmers’ co-operative is proposing to pump water from the Waitaki River into the Ngapara-Enfield area southwest of Oamaru.

Green believes farmers on the Waitaki plains have one of the best irrigation schemes in the country. The Waitaki’s comparatively clean water optimises pasture growth and the health of stock, while the absence of seasonal restrictions on abstraction is a blessing.

[Chapter break]

To get an idea of how popular the Waitaki River is for recreational pursuits, take a drive along State Highway 83 to Omarama during the Christmas holidays. Initially, there’s not much to see, just glimpses of a wide floodplain winding its way up an even wider valley. Any jetboaters or anglers on the river are hidden from view by the dense tangle of gorse, broom and willows.

But once you reach Kurow and drive along‑side the hydro lakes things change dramatically. Campers, boaties, water skiers, windsurfers and anglers are everywhere. At certain times of the year the Waitaki is so popular space is at a premium. Anglers stand shoulder to shoulder at the Waitaki mouth, forming a human picket fence when the salmon are running, and thousands of holidaymakers jam into lakeshore camping sites over the Christmas period.

Sailor’s Cutting, Haldon, Waitangi and Glenavy are crammed full of tents and caravans. The former hydro towns of Otematata and Twizel have also become thriving holiday spots, with comparatively cheap houses making them an affordable alternative to high-priced Wanaka and Queenstown.

The Waitaki is renowned for its fishing. A National Angling Survey conducted in 1996 rated the Waitaki catchment the fourth most popular fishery in the country, with an annual effort of 86,131 angler days. Anglers are drawn by excellent stocks of brown and rainbow trout found throughout the catchment and a major chinook salmon run in the lower river, a combination unique in New Zealand waters.

One angler who knows the river’s fishing spots better than most is Graeme “Squid” Warren, a professional fishing guide and former power-station operator at Waitaki Dam. When Squid is not out fishing or guiding he can be found tying flies in his Kurow home, dreaming up an excuse to get back out on the river.

The Waitaki may not have the international reputation of Taupo but Squid reckons it’s a superior fishery. “It offers so many different types of fishing—there’s a caddis hatch, great nymphing, salmon fishing, clear water, milky water—and it all changes so much in a 24-hour period. It’s a big river with big water, and if you hook a fish it’s a real challenge to hold on.”

One of the most popular events on the angling calender is the Waitaki salmon fishing contest. Up to 700 anglers make an annual pilgrimage to enter the contest, although catch rates vary wildly from year to year. If the contest coincides with a lull in the upstream migration of salmon then most anglers go home emptyhanded. In 2001, 340 anglers could manage only 34 salmon over four days, which equates to approximately one salmon every 320 hours of fishing.

The past three years have been lean ones, but despite the frustration experienced by anglers the vast majority will be back again next year. Self-confessed salmon fishing fanatic Steve Hayward, headmaster of a local primary school, explains:”Salmon fishing is like an incurable disease. Once you’ve got the bug, you can’t stay away. There is nothing to match the thrill of hooking a big salmon in fast water. Plus they are an exquisite table fish.”

Non-salmonid species such as whitebait, eel, flounder, kahawai, mullet and lamprey are also popular at certain times of year. Whitebaiters line up at the Waitaki mouth during the peak season, from October to November, while anglers fish for kahawai that congregate off the mouth in large schools in November and December.

Duckshooters, jetboaters, kayakers, bird watchers and tourists all use the Waitaki. Lake Pukaki, with Aoraki and its surrounding greywacke giants, Sefton and Tasman in the background, would have to be one of the most photographed scenes in New Zealand.

While Fish and Game’s Graeme Hughes is satisfied that the Waitaki River is in good shape today, he is less certain about the future. Meridian is conducting preliminary investigations into the lower river’s suitability for yet more hydroelectricity generation and has indicated that a canal system would be viable between Kurow and Black Point. A favoured option involves diverting most of the river into a canal, leaving a residual flow of 80-120 cumecs in the natural riverbed. Engineers and scientists have concluded that a residual river would sustain an adequate fishery, but Hughes is less convinced by the proposed development.

“One of the greatest things about the Waitaki is its size—you can spend all day on it and not see another person. The big-river aspect will be lost if that development goes ahead.

“I’ve also got doubts about a residual river supporting a decent fishery. There are too many uncertainties for scientists to predict what will happen if they take away 250 cumecs—nature’s too complex.”

Hughes says that at the moment a functional compromise exists between the demands of power companies and other users, but predicts this delicate balance will be disrupted if the lower river is further developed.

“The Waitaki is something special for so many people—I don’t think they should risk taking that away.”

It looks like turbulent times ahead for the river of tears.