Torpedo carnivore

Reaching more than six metres in length with a bite force of nearly two tonnes, the great white shark is the most fearsome predator on Earth. Yet despite their reputation as maneaters, great whites are protected in New Zealand as a vulnerable species.

Mike Fraser picked his way over the rocks of Campbell Island’s Northwest Bay, pulled a thick neoprene hood over his head, slipped on his fins, placed his mask over his eyes, blew a couple of rasping breaths through his snorkel, then slid into the water. It was frighteningly cold, barely 7ºC. He looked back to see his four colleagues enter the water, and together they swam through kelp that swayed rhythmically in the Southern Ocean surge like twisted ribbons in the wind. The sea lions, which can normally be seen tumbling through the weed, were conspicuously absent.

Fraser and his friends spent 20 minutes investigating the rocks and crevices of the bay and examining the sandy bottom that shelved gradually out to sea. He was hoping, in coming days, to snorkel with the southern right whales that linger at Campbell Island each April.

This far south, sharks were the furthest thing from his mind—it was believed at the time that great whites never inhabited water less than 10ºC. In fact, he didn’t even see it coming.

Like a train hitting a bicycle, the force of the impact drove him deep underwater and knocked the mask from his face. The jaws of his assailant had closed firmly over both arms, sinking its teeth through the neoprene wetsuit and into the bone. He was driven up to the surface again, and in a moment he will never forget, Fraser turned his head and looked at the shark. It was a single moment of clarity in the thrashing white water. A dense, black, expressionless eye stared back. Pushing hard with his knees, Fraser managed to tear his left arm free.

Then suddenly, numbing relief. The shark turned and swam off, and Fraser looked down to see the mangled remains of his right arm. It had been torn off at the elbow.

On Anzac Day, 1992, after losing half his blood, and lying on the beach for 15 hours in the care of his colleagues overnight, Fraser endured the longest single-engine helicopter rescue in history to survive with the inauspicious title of the world’s most southerly shark attack victim.

But for everything that made this event extraordinary, it exemplifies many of the things that make shark attacks similar. Few are fatal, and in almost all attacks on humans, the sharks never return for a second bite. Scientists believe that this is because shark attacks on humans are cases of mistaken identity and that the predators favour fattier, more energy-rich food sources.

Just four people were killed by sharks (of any type) in 2008, worldwide. And in return, humans commercially harvested some 100 millions sharks. While few great whites are directly hunted, their jaws are in demand as trophies, fetching up to $50,000 on online auction sites. They are also victims of accidental capture in gill nets, shark-control programmes, and vulnerable to over-fishing. As a result, the greatest predator on Earth is itself declining in numbers and now considered endangered.

Seventeen years after the event, Mike Fraser reclines in a roller chair in his Albany office, surrounded by the clutter of a man still obsessed by the sea—underwater video housings, plans of foundered wartime ships. He pulls up his shirt sleeves, easing aside the plastic prosthetic to display a myriad of 10 cm long scars that still cover each arm. The deep kelloid gashes are evidence not of the attack so much as the escape, the path of dozens of teeth as his arms were torn free.

“I can’t understand why people want to kill apex predators,” he says. “They’re just doing what they do.” For a man who has been partly devoured by a shark, his philosophical perspective raises a salient question. Why on Earth would anyone want to protect a man-eating predator?

They don’t even seem to be ecologically important. There are plenty of species we save or control because of the powerful structuring role they have on the environment—fundamental building blocks such as krill, or destructive pests such as rats. Conservation work with such structuring species can transform an ecosystem. But as far as anyone can tell, apex predators like great white sharks have little structuring effect—their numbers are not large, they take few prey, and have no natural predators—with the exception of very rare territorial attacks by orcas or larger great whites.

We choose to conserve species like great whites for another reason—for their singular, intrinsic value. They are fabulously fit for purpose, a design so perfect that they have remained unchanged for millions of years. And aspects of their anatomy are utterly unique—they have organs not present in any other fish, and a suite of senses beyond our realm of experience—eyes with 10 times the light sensitivity of ours, an astonishing sense of smell and the ability to feel vibrations and chemical signals in water in a way that scientists are just barely beginning to grasp. An extra sense allows them to “hear” electrical signals as low as five billionths of a volt per centimetre—the equivalent of electrodes connected to a flashlight battery 16,000 km apart in the ocean—opening a sensory realm of electrical fields that we cannot begin to imagine.

These abilities continue to baffle scientists and provide inspiration for emerging technologies. But we also revere them as charismatic mega-fauna, and as killing machines—one of the few predators that continue to take human lives.

Peter Benchley’s novel Jaws and the subsequent success of the blockbuster film brought the cinematic power of Hollywood to vilify the great white and have fanned into flame the public appetite for fearsome predators. But this is a response which Harvard sociologist Edward O. Wilson suggests is deeply rooted in our own evolutionary history. “We are not just afraid of predators,” he says, “we are transfixed by them, prone to weave stories and fables and chatter endlessly about them, because fascination creates preparedness, and preparedness survival. In a deeply tribal sense, we love our monsters.” And there’s nothing like the tingle of mortality to make one feel truly alive—just ask Mike Fraser.

[Chapter Break]

“It’s a bugger of a place to fish,” warned the ferry skipper as I crossed Foveaux Strait to Stewart Island, one of the most notorious aggregation points for great white sharks in New Zealand waters. “Between the seals and the sharks you don’t have a show of getting your line up with the fish still on it.” This time of year there are numerous sightings of great whites, particularly around the Titi Islands just off Half Moon Bay.

Clinton Duffy has been spooning a fragrant bouillabaisse of minced albacore tuna into the sea off these islands for the last week. He’s wind-whipped, stubbled and, today, a little frustrated by the keen lack of subjects. “We’re at a perfectly good seal colony, with perfectly good berley,” he calls out to no one in particular. “Come on fishy fishy fishy, what’s wrong with ya?”

Duffy commands something of a celebrity status in the halls of DOC’s regional offices—people sing the Jaws anthem, “dun-nuh, duh-nuh, duh-nuh”, when he passes their cubicle—and seems to be the media’s go-to guy whenever anything bites a swimmer. But the questions he ponders now are harder to fathom than anything the press pitches at him—indeed, they will be central to the conservation of great whites.

[sidebar-1]

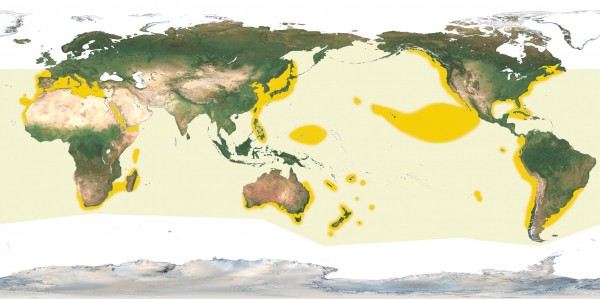

We once presumed that great whites, the world’s largest predatory fish, were only found in coastal temperate waters, but now know that they migrate through open ocean to the tropics as well as subantarctic latitudes. Why? We’re not entirely sure. Where do they breed? We don’t know. Where do they give birth? No idea. How often do they breed? How old do they get? How many are there? All Duffy can do is shrug.

However, he and a team of scientists are piecing together clues from international research and chance observations by fishermen and sifting through an astonishing volume of data he collects from satellite tags that offers some of the best clues to their enigmatic movements, and their continued survival.

So far the team have tracked great whites from Stewart Island to Australia, and from the Chathams to Tonga. They have reams of data on where they go and when, knowledge that challenges much of what was known about the species at the time of Mike Fraser’s attack.

“We were wrong about just about everything back then,” explains Duffy. “We only knew what could be observed on our own coastline. But now with satellite tags we can track sharks to locations where no one is there to observe them.”

Consequently, the range of great whites has extended substantially from its assumed boundaries to take in remote and frigid latitudes of Alaska and well south of New Zealand’s subantarctic islands.

But gathering data is one thing, extracting the reasons for these massive trans-oceanic journeys is more difficult. Many of the tropical destinations so sought after by great whites are dead centre in the middle of nowhere, far from the nearest land and with nothing but 4000 m of deep blue sea beneath them. What’s the big attraction?

Here the scientists, so wedded to facts and empirical certainty, must flex their right hemispheres, look for unlikely possibilities, draw tenuous hypotheses based on little-known migration patterns of possible prey. It seems likely, for instance, that the great whites that Duffy has tagged at the Chatham Islands time their winter tropical holiday to coincide with humpback whale migration— specifically, the times and locations humpbacks are known to calve.

Duffy is also convinced that the very large sharks are female, and that they are pelagic—that is migratory, open-water species—most of their lives. Great whites in New Zealand waters commute between breeding grounds and known feeding opportunities either in the subantarctic or the tropics. In contrast, males are smaller, often found in coastal rather than open water and never attaining the size of the femme fatales. In fact, the largest male shark ever recorded is 5.5 m long, which is a large shark by any measure, but dwarfed by accounts of 7 m females.

The subject of size is always seized upon with enthusiasm when it comes to fish in general, and sharks in particular. Chatham Island fishing legend Fred Abernethy reliably recalls a 9 m shark that straightened out the hook, there have been persistent historical accounts of 7.5 m sharks in Tory Channel, and an 8 m shark was once harpooned in Fouveaux Strait.

But it is persistent reports of very large and very small sharks around the beaches of Northland that make Duffy most curious. Because very large sharks, as we have said, are almost always female, the presence of juveniles at the same time is indicative of shark conservation’s holy grail—the birthing areas. Evidence of this, and the areas in which they breed, are absolutely crucial geographical stakes in the map of their conservation.

[Chapter Break]

The water at Edwards Island sparkles with dancing sooties. Shy albatrosses look on with porcelain complexions and Buller’s mollymawks peer down their harlequin snouts at the long slick of tuna oil extending away from the transom with the tide. Then the call goes up, “Shark on!”

Twenty metres behind the boat a fine dorsal fin cuts through the berley trail, steadily, deliberately coasting towards the boat. As it comes up to the transom it rolls gently on to its side, exposing the two-tone battleship grey and white colouring, the jet-black eye, the sharp lines and voluptuous curves that make sports cars both objects of desire and lightning quick.

As it slides along the port side, skipper “Barney” Brown calls the tail at the transom and Duffy lines up the snout with measurements scribed on the gunwale of the Jester—at least 4.1 m long, and probably approaching a tonne.

[sidebar-2]

This is a large shark, but it’s no phantom menace, no monster. For all its obvious mass it moves slowly, gracefully, turning merely with a twist of a pectoral fin. There is little noise but the hiss of the dorsal fin slicing the surface like the sound of slowly tearing a page from top to bottom.

Another smaller shark appears; soon there are three circling the boat. One has been tagged in previous days and is identified as “Ella”, the other an untagged juvenile.

“It’s at the bow going down the port side,” calls Warrick Lyon, a NIWA scientist. “Ella’s on the quarter,” calls the skipper from starboard. DOC’s Phred Dobbins hauls in the throw baits hanging from the transom—they’re there to entice the sharks, not to be eaten. Soon, another great white is at the boat and Lyon is calling their movements like an aircraft controller. “The juvenile’s gone under the keel, coming up on the port side, Ella’s coming down to starboard.” Kina Scollay, a paua diver and himself victim of a great-white attack, tracks the movements of each shark on video, capturing frames that can be used later to identify each member of the fishy cast by scars, tag positions and colouration variations.

There are sharks everywhere. A note to readers: Never swim at Edwards Island in April.

The largest shark approaches the port side, Duffy ominously following its form with a long prod. At the end is an inch-long stainless-steel spike and a pop-up archival transmitting (PAT) tag that will track the location of the shark every few seconds for the next 11 months—invaluable data for understanding the animals. Tags attached to other sharks have all been set to just nine months to avoid failure due to waning battery life, environmental fouling and data corruption. But Duffy’s taking a punt on this last shark to reveal a more complete pattern of migration. It’s worth a stab.

When the long shadow is parallel and close to the boat, Duffy strikes, ramming the tag into muscle at the base of the dorsal fin, and pulls out the spike. The shark twists a little, but seems surprisingly unconcerned.

This week, Duffy and the team have identified 15 different great whites in the same location and tagged eight with PAT tags. They’ve been named, measured and photographically identified—Ella, Phred, Miranda, Chopper, Barney—namesakes of children, friends and family of the crew. Particularly encouraging, Duffy has identified two sharks seen at Stewart Island last year, adding to a growing body of observational evidence that these sharks are creatures of habit, returning year after year to favoured feeding grounds.

[Chapter Break]

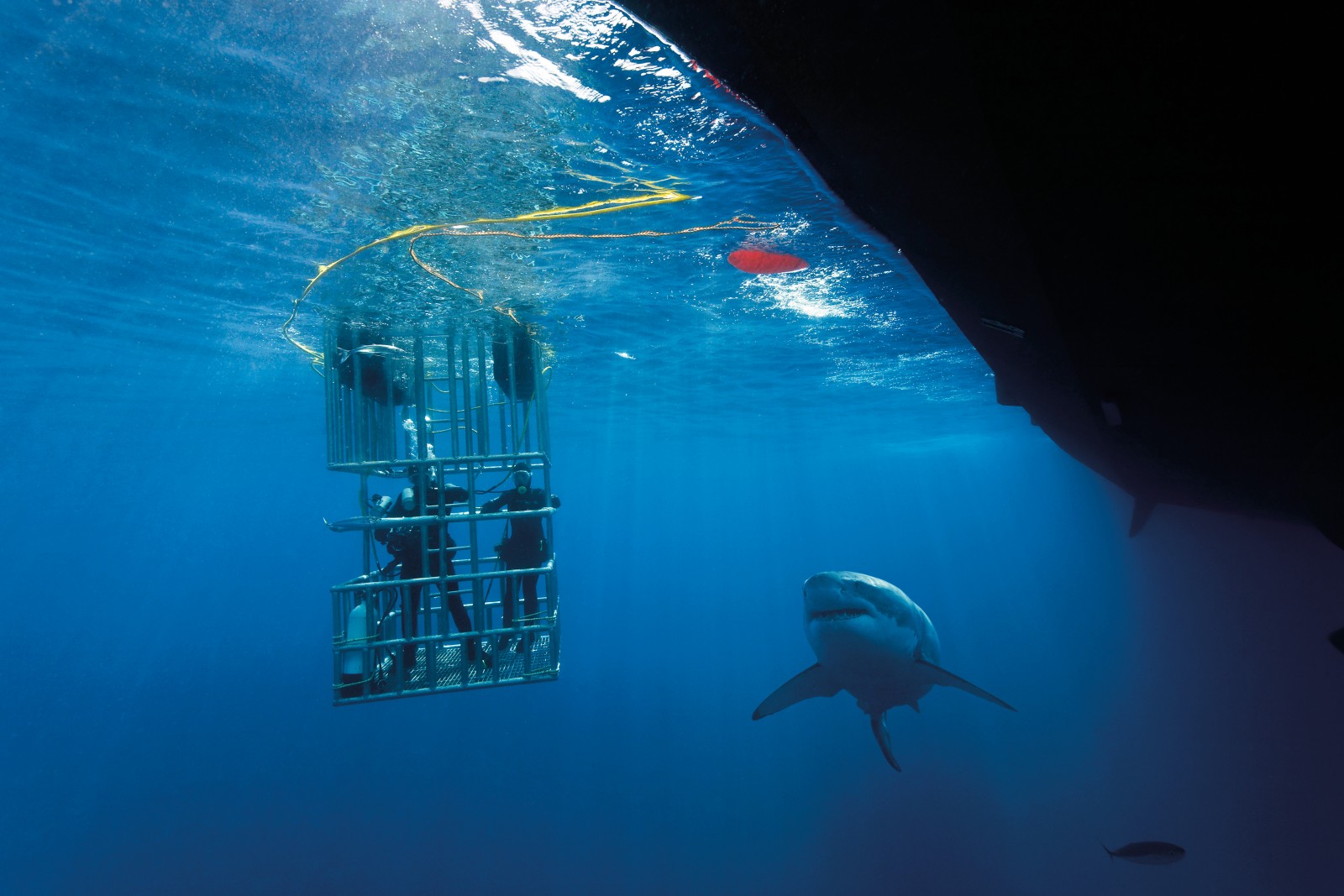

Not everyone is so keen on great whites, especially not the paua divers propping up the bar in Half Moon Bay. Rumours that a mainlander has started a cage-diving operation for tourists, chumming the same water as the local divers extract their livelihood from, have turned out to be true.

“You don’t have to spend long at the South Sea Hotel to hear stories about great whites,” says Storm Stanley, who’s been paua diving on Stewart Island for years and is now chairman of the Paua Industry Council. “But these are dangerous creatures. Deliberately attracting sharks with chum then putting divers in the water modifies their behaviour. They start associating people with food.”

Local paua divers are not just hot under the collar—they’re terrified to go in the water. “You’ve suddenly got a predator-prey thing going on,” says Stanley. Whispers in corners even suggest that they will begin slaughtering sharks if the cage-diving continues.

Duffy is less convinced that behaviour modification is anything new. “They certainly associate boats with food,” he says. “But that’s because cod boats have been chumming and cleaning fish here for years. It’s harder to imagine they’re going to attack a diver because of some chum.”

But it’s hard to speculate on the motivations of a one-tonne fish—this is not an animal we fully understand. With every tag returned, scientists are still learning more about the sharks, their habitat and range under constant re-evaluation, even extending as far south as the cold waters of the subantarctic where Mike Fraser was attacked. In part, this is due to the peculiar anatomy of the great white that allows it to exist in regions where few other sharks can survive.

The body temperature of fish, and indeed most creatures on Earth, fluctuates with their environment. And because of this, these ectothermic (cold-blooded) creatures tend to live where the average environmental temperature is conducive to their physiology. However, mammals and birds are endothermic (warm-blooded), equipped with a revolutionary anatomical system to regulate our own internal temperature—an elaborate trick that has enabled us to extend our range across an enormous variety of habitats.

Like all fish, most sharks are also cold-blooded, but the great white and at least half a dozen other species of laminoid sharks have developed a special organ, a network of blood vessels called the rete mirable that uses heat generated by swimming to warm the brain and stomach. The result is a heat exchanger so efficient that it can maintain an internal temperature up to 14ºC above the ambient water temperature.

And the pay-off is enormous. A 10ºC rise in body heat can result in a three-fold increase in the speed and strength of muscle contraction—supercharging the great white to maintain faster swimming speeds for longer, increase the efficiency of digestion and therefore also the amount of caloric energy it can consume in a given period. But above all else, the greatest advantage is an extension of range into colder, richer water.

It now seems possible that a great white could inhabit water as cold as 7ºC. Possible, but also very expensive. When you or I leap into a cold pool, blood flow is diverted to concentrate around our vital organs—hence the white fingertips and blue lips. We also begin to metabolise rapidly, converting food and body fat into energy. It is the same for sharks. In cold water, a great white shark burns energy like a blast furnace and may require up to 10 times as much food as a cold-blooded shark of a similar size. Their distribution is therefore dictated by food sources—typically large prey of high calorific value.

[sidebar-3]

This suggests that whatever Mike Fraser’s leviathan was doing at Campbell Island, it was not sight-seeing. It was there for one reason alone, dining. And in cold water it would have been more sensitive to the calorific value of its prey than ever, which is probably why it never returned for a second bite. So if Fraser wasn’t really a la carte, then what was?

Seals, sea lions…whales. Now there’s a high-value target.

Obscure clues begin to reveal an obvious pattern: In April every year, southern right whales and their calves migrate north from Antarctica, stopping at Campbell Island. Ironically, it seems that Fraser and the great white shark that attacked him were looking for the very same thing that spring day in 1992—an encounter with southern rights.

[Chapter Break]

Back at Stewart Island the crew continue dispensing a slurry of “marinara” over the side. The stench permeates every pore and hangs in particularly offensive concentrations in the bilge. A ragged bouquet of albacore tuna hangs limply on the throw line, weaving in the ebb tide.

Suddenly a blunt head erupts from the depths shattering the tranquillity with a geyser of white water. It surges a metre out of the water, taking the bait in its mouth; the rope snaps taut with an audible crack and the body slams back on to the surface, whipping it to foam with its tail. Thrashing, heaving, displacing water in huge waves, pounding like a pile driver. Eyes rolled back in blind fury. Teeth tearing at the bait. Heavens, the teeth! Framed with fleshy pink, the jaw extends forward for the kill, snout pulled up and creased, the whole head of the animal distorted for the benefit of biting.

The boat lurches violently and Duffy leaps at the line, hauling it back in. The 800 kg shark competes for control—it hardly seems fair. But, as if it were ever a contest, Duffy loses, the green polypropylene line burns through his hands and he leaps backwards to avoid it. With the crack of a bull whip, the line is sheared off and ricochets back into the boat. You couldn’t have made a cleaner cut with a razor blade.

The waters of Edwards Island close over the top, fizzing with spume.

It was an emphatic demonstration of power, and the illusion of grace we witnessed earlier is replaced instead with a profound sense of dread. Jekyll had become Hyde, the monster had emerged and revealed its most monstrous tendencies. All that remains are the swirling vortices of where the beast has been; the power, the fury, slips silently into the deep channel with the shark.

This individual carries on its back the hope of a species, a tag that may reveal the most important habits and habitats of great whites, recording where they go this year, to help us conserve them next year.

In 2007 we protected great whites in New Zealand because we revere them as super predators, are fascinated by the mysteries of their migrations, and have plenty to learn from them yet. And while great whites continue to attack and kill humans, we resolve to protect them from ourselves—to our enduring fascination, and even our peril.