Top of the South

As the second New Zealand Company settlement, there were high hopes for Nelson. But like its quayside coal-fired power generation scheme, that became a fish processing factory, then a seafood research facility, the city had a way of defying its founders to offer something completely unique.

Nelson was founded on a fable.

And that is exactly the feeling you get as you approach Christopher Vine’s central Nelson home, that sense of entering a fairy tale. Shadowed by Church Hill, it sits well back from the narrow lane that once hosted the city’s 19th-century synagogue, obscured by an unruly tangle of trees that spill across a winding path. You push past a branch of spring blossom, glance to check your footing, and when you look up, there is Vine’s home of the past decade in all its shambolic glory—a patchwork of additions and renovations, held together by salvage yard treasures, ingenuity and wit.

Vine, an architect, writer, potter and longtime Nelson identity, has rescued the 150-year-old house—“bulldozer material” when he bought it—using recycled materials that speak lovingly of Nelson’s past. Timber panelling from the ruins of the Nelson Provincial Chambers, bowled in the 1960s despite protests from Vine and others, line an internal wall. At the bottom of the garden, the 79-year-old is using bricks that were ballast in the first settlement ships to rebuild a small shed.

A stone’s throw away is the cathedral, an edifice of Takaka Hill marble that for many symbolises Nelson. Yet Vine and his eccentric endeavour arguably reveal more about this part of the Top of the South. The grand and bustling city envisaged by Edward Gibbon Wakefield’s New Zealand Company and seemingly confirmed by the commissioning of a cathedral never came to pass. From its beginnings, Nelson took a very different path from that hastily drawn up and recklessly promoted by its architects in London.

Modest in scale, less affluent and far more peripheral than had been hoped, Nelson was nevertheless blessed with an ideal growing climate and pockets of wonderfully fertile land. As a result, the nascent city attracted not the ideal pastoral settlers, but rather orchardists, hop growers, artisans, artists, commune-founders, religious cranks and creative thinkers.

In his history of the Nelson region, historian Jim McAloon emphasises the critical importance of geography. “Economic problems—in the sense of getting a living—have dominated Nelson’s history,” he writes. “Nelson has had to contend with isolation, rugged landscape and highly variable soils. Turning unpromising circumstances to advantage is a major theme.”

Or as Vine puts it, over soup shared in the conservatory he has tacked onto this sprawling house of his, “I’ve always thought of Nelson as being like an island within an island, always very much its own place. Take the railway—it just never made it here.”

Erudite, self-deprecating and occasionally curmudgeonly, Vine has invented a life for himself in Nelson in a way that bears out McAloon’s theme of self-sufficiency. Brought up among English privilege, Vine abandoned a promising architectural career in London and brought out his young family to escape the shadow of The Bomb, part of a wave of Northern Hemisphere migration to Nelson during the 1960s and 70s.

He settled his family on a small holding up the Teal Valley, in the lee of the Whangamoas, a mountain range that separates the region geographically and culturally from Marlborough.

“I had a passion for being beside running water. In Nelson, apart from the big rivers, the waterways come down to almost nothing in the summer because of the gravels underneath us,” says Vine. “But the Teal doesn’t.”

The attempt at farming was a fiasco, he laughs, the land infertile, covered in rocks and every kind of noxious weed imaginable, and Vine didn’t have a clue how to work it. Casting around for another way to support his family, he bumped into someone who’d just started a pottery studio out at Waimea.

By the late 60s, pottery in Nelson was beginning to look like a viable career move. Mirek Smisek, the Czech refugee who pioneered the craft in the region, had been joined by English migrants Harry and May Davis at Wakapuaka and Jack and Peggy Laird out at Waimea.

Vine began selling pots. “Initially they were pretty bloody awful, but I became reasonably adept. And back then you could make an adequate living, particularly if you sold from the door.”

Then he tried his hand at painting murals, wrote columns on architecture for various newspapers. He even lived briefly in Auckland. But his “onshore island” called him back.

“I do think this place has a soul,” he says. “I think of the way that Nelson is sheltered by these hills around us—I imagine them as being like hands—which give us this privileged climate. Yes, it has a sort of introversion, but maybe that’s not such a bad thing sometimes.”

Yet it’s not quite a land for romantics. They come as dreamers, perhaps, pulled by the climate and the cheap land, but, like Vine, to stay they have had to adapt to the economic realities, create their own jobs, work hard. There are few big employers in Nelson. Many of the staple industries are seasonal, and the place shuts up shop during winter. “Historically,” he says, “people who weren’t prepared to live by their wits have had a bit of a hard time of it in Nelson.”

[Chapter Break]

It rarely appears like a crucible of tears and struggle, of course. Standing at the top of the granite cathedral steps, from where the eye travels down Trafalgar St to a distant glint of cerulean blue, you get a sense of what those founding architects imagined for New Zealand’s second colony, a place of hustle and enterprise, central to national affairs.

Yet less than one year after it was made the seat of an Anglican diocese and granted city status, Nelson was dismembered. With separation from Marlborough in 1859—the result of years of political tensions between the small farmers and artisans and the big run-holders of the Awatere and Wairau valleys—Nelson’s distinctiveness was confirmed, writes McAloon. “The province became an entity in which agriculture rather than pastoralism was dominant.”

“I think it must have been a great blow to the pride of Nelson when Marlborough opted to become separate,” remarks Vine. “This place remained primarily a province of peasants, really, operating smallholdings, doing interesting things like orcharding, tobacco farming, hop growing and now viticulture.”

You can read that diverse history on country byways like Neudorf Rd, which spools out through the soft Tasman hinterland, backdropped by Mt Arthur and bulletpointed along its length by the relics of tobacco and hop kilns. Today, the road is populated with cheese plants, cider orchards, olive groves, wineries, studios and furniture workshops. It feels like you have turned off the Moutere Highway and into Europe.

A couple of kilometres along, I find Neudorf Dairy, a sheep-milk cheesemaking operation owned by Brian Beuke, descendant of one of the original German families who settled the district in the 1850s. They came to the Moutere, says Beuke, “because the land was cheap and available and they were very poor”. For the most part the land didn’t make them rich, but years of hard work transformed subsistence farming into something more viable.

It’s a very different landscape now along Neudorf Rd. Beuke, who started milking East Friesian sheep a decade ago and built the dairy in 2006, is almost last man standing.

“When I was at primary school, 90 per cent of the kids were from families who made a living off the land,” says Beuke, who can remember the days when stock were driven down Neudorf Rd. “By the time our children were at school 20 years ago, they were probably the only ones left. The small farms have rapidly become uneconomic and most of this area now is lifestyle blocks.”

That transformation of Neudorf Rd and the surrounding district really began in the 1970s, according to Judy Finn, who with her husband Tim founded Neudorf Winery at that time.

“There were a whole lot of new people to the district, and they brought a tremendous range of skills. It was the fag-end of the back-to-the-land movement so there was that romantic vision of carving out a living that was left over from the 60s, but it was slightly more sophisticated—we’d all got past the commune idea.”

The land the Finns found on Neudorf Rd, near Beuke’s place, proved world-class. North-facing and with the free-draining Moutere clay—which Nelson’s orchardists have always maintained grows the district’s best apples—the terroir at Neudorf produces complex, texturally rich wines that routinely win prizes.

Yet at the time the Finns planted their first vines, they were regarded as wildly eccentric. Herman Seifried had started his winery at Upper Moutere, but winemaking was still fringe. Judy Finn recalls there was “bewilderment” among the established community at their venture and all these new arrivals. “When we arrived, the area still had the strong German ethic. We really had to prove that we could work hard.

“It’s become a very strong community, one in which most people produce something in that European style—wines, apples, boysenberries, mushrooms, cheese; there’s a guy making knives up the valley, another who makes wooden furniture. It’s never been a fashionable area like Mapua, never chi-chi; it’s just very real.”

That said, Finn acknowledges the pull that the area exerts on what you might call practical dreamers. “It’s an area where people come to live out their dreams,” she says. “If you’re coming from Germany, or Switzerland, you think, ‘What will I do? I’ll grow gourmet mushrooms and sell them in risotto packs’—mad things like that that tend to work out well. It’s part of the charm of this place, that nothing is unreasonable.”

Up the road, I spot the perfect metaphor for that notion, in the form of one of Michael MacMillan’s giant concrete sculptures. MacMillan, a fourth-generation sculptor and potter, lives with his wife, Jackie, and young family in the 1870s Neudorf School, using a pair of shipping containers in one of Brian Beuke’s adjacent paddocks as his workshop.

When they moved here from Pelorus Sound a few years ago, MacMillan found his work changing, becoming less fluid and elemental, more reflective of the heavily cultivated hinterland around him. The concrete is corduroyed like a ploughed field, the shapes wheel-like and often threaded with sheaths of grape-vine cuttings retrieved from the Finns’ winery.

“It’s an extreme environment here, too, though. When we arrived, this place was in drought and it was 36 degrees; and in winter we have had snow around the house,” says the sculptor, who works out in the elements, under a tarpaulin strung up next to one of the containers.

Their converted schoolhouse served for years as the Neudorf Community Hall, and the MacMillans are constantly finding bits of old crockery, bottles, coins and other artefacts. Neudorf Rd itself was a main coach route and a link to the Baton Valley goldfields. The remains of a 19th-century guesthouse still cling to life—just barely—closer to Dovedale.

Some things haven’t changed, however. “It was all about hard work and commitment here historically, and I think that’s still the case for people on this road,” says Jackie MacMillan. “Everyone works bloody hard at what they do. And it’s still subsistence—the money comes in for a while, and then it doesn’t.”

[Chapter Break]

It was a textbook example of non-violent action: nine women—among them Sonja Davies, who would later become a Labour MP—sat on the tracks for six days in 1955 until they were arrested in an attempt to stop the demolition of the last of the Nelson Line*. It made no difference, and by the following year Nelson had lost even this vestigial railway link to the world.

Isolation has always been Nelson’s bane. During the 1960s, writes McAloon, as the region’s relative prosperity declined and more young people left to find work, “it reinforced feelings that Nelson was backward and neglected by central government”.

But that sense of being out on a limb is also deeply attractive. If there is a spiritual home to New Zealand’s commune movement, it’s arguably Nelson and Golden Bay, where cheap land, sunshine and seclusion were hippy catnip during the 70s.

Nelson’s original commune, however, was something quite different. “We have never tried to be shut away,” says Kathy Francis, a longtime member of the Riverside Community in Lower Moutere. “In the early days, they wanted this place to be the yeast that moved the world.”

We talk while walking down from Francis’s “granny flat” to collect her milk, past a cluster of modest wooden houses and the communal lounge and kitchen, past “the Oval”, which is shaded by 50-year-old oaks that Francis and a sister planted from acorns that they brought home as kids from Lower Moutere School.

Their parents were among the Christian Pacifists who founded Riverside in 1941 with the intention of putting beliefs into action—representative of a Nelson tradition of political activism behind liberal causes such as human rights, one that consistently bumps up against Nelson conservatism. Like most of the Riverside men, Francis’s father was jailed as a conscientious objector during the war years. She can remember how once, as they waited for a bus, his pacing suddenly evoked memories for him of being in a cell.

“They wanted to set up a way of life according to Christian teachings, rather than the Church. They weren’t church people at all—they were too far out to the edge; the Church couldn’t cope with Riverside. They hoped that new members would come from the Church, but they never did. They came from all sorts of much more disreputable places, from here and there, and later they came from the hippy movement.”

Francis, who eventually raised four children in the community, came back as an adult member at the end of the 70s. By then, Riverside had shed its Christian requirements—“It was a case of change or die,” as she put it—but there was still friction with the new arrivals. She recalls “big conflicts” over spraying in the orchard.

Some of the newer Nelson communes, meanwhile, regarded Riverside suspiciously. “We went to work all the time and we lived in conventional houses and had structure. There were a lot of other communes around that didn’t like Riverside—they saw it as Establishment. But over time we came to be like the older brother, helped them to set up trusts, loaned them equipment and money—we had some money then; not any more.”

This self-supporting communal living hasn’t been an easy road in the 21st century. Riverside’s dairy farm squeaks by, but the orcharding fell away in the 90s, too small to be economically viable. A cafe launched 10 years ago to supplement the farm income does well to break even; likewise the garage.

It’s a subtly different place, too. Income is pooled, and big decisions still arrived at by consensus. But working patterns have diversified; people see less of each other, and communal meals are organised less frequently.

Yet this year, five new families were taken on as members. It means more mouths to feed, says Francis, but it shows Riverside has a future. “From the mid 90s, I felt like we were just hanging in there, but I don’t feel that now. We’re moving forward.”

How does she account for Riverside’s longevity, given so many other communes have closed long since or descended into chaos? “I think it’s partly because we have a strong philosophy that this isn’t just about us wanting to live a nice life, that it goes a bit beyond that.”

“And it’s also our economic structures—when the community is in a mess, you still have to go to work.”

[Chapter Break]

It’s a vast space, Darryl Frost’s Tasman workshop, more akin to a boatbuilder’s yard than a potter’s studio. Intruding vines twist along walls, and sparrows flit through under its high iron ceiling. Yet somehow Frost has pulled off the feat of making the place feel cluttered. There is work everywhere; warped, organic forms, caught in a no man’s land between solidity and mishap.

Those signature Frost shapes are the result of a wood-firing technique known as anagama. At the bottom of his Kina Beach Rd property he’s built a tunnel kiln that steps seven metres up a slope. During a firing, he and a team of friends have to keep feeding this thing wood for five days and nights straight. A rough piece of text scrawled across a nearby beam gives some idea of the headspace: “In which reality am I?” it says.

It’s a demanding process, involving a randomness that Frost cherishes but which is also nerve-wracking. “It becomes about where you place the work in the kiln, the direction of the flame, what wood you use, how much ash flies up, who is firing the kiln—because people fire in different ways. It takes me a week to load it, nearly a week to fire it, and at the end of it all, the way you close it down is as critical as anything else, because you can change it in that moment from being super grey and matty and crystalline to something shiny and gooey. And it’s when you are most exhausted that you have to make that critical decision.”

Despite that element of happenstance—or perhaps because of it—the work captures this landscape. You can see Tasman’s estuarine waters and its beaches. “I use kinas off the beach here, clay from Golden Bay, ash from the trees around here. My work is totally about where I live,” says Frost, who came to Nelson on a house-truck tour 27 years ago and just never left.

He’s living out that story you associate with Nelson, of making a living from his art, and his art from the land.

It’s getting tougher, though. There used to be 180 potters, he says; now there are roughly 18 on the arts trail. “Cheap imports have killed it, and it’s a hard way to make a living. But for me, there’s something about it that keeps you alive.”

Was it ever an easy ride, though? Anna-Marie White, curator of Nelson’s Suter Art Gallery, has found a letter in the gallery’s archives from Colin McCahon, who lived in the region off and on for 10 years. In the letter, McCahon inquires of a gallery staffer about the fate of one of his paintings, gifted to the Suter by the writer John Caselberg.

“It was the first McCahon ever gifted to a public gallery,” says White. “McCahon writes: ‘It’s had a horrible life there; Nelson is a cruel city to people and to paintings’.” She laughs. “I want to make that a bumper sticker but my boss won’t let me.”

White took on the curator’s role five years ago. From New Plymouth—another New Zealand Company town—and of Te Atiawa descent, she mixes the forensic and the good-humoured in her insights on Nelson. And she has a clear-eyed understanding of the region’s role in this country’s art history—including the romantic myths.

It wasn’t until the 1950s that you could say there was anything special or unique about Nelson’s art scene, remarks White. “That’s when you get the post-war European migration and that artisan tradition which gave rise to the jewellers, the weaving guilds and the potters.”

Painters? You think of McCahon, who painted several important paintings in Nelson and Golden Bay, Doris Lusk, who was here, too, and especially of Toss Woollaston, out at Riwaka. But White’s take is that these artists were made elsewhere. Woollaston had his first serious show with Peter McLeavey. “The big canvases we associate with him come from that period, so he was really made in Wellington.

“We have all these wonderful ideas of Leo Bensemann folk dancing in Golden Bay, or Rita Angus hanging out at Riverside as an anti-conscription activist, of all those artists getting together in Nelson, this romantic notion of workers’ cottages at Mahana or Riwaka. But they were here working seasonally. They came because they could get money to live, to support young families. This idea that Nelson plays a critical role in New Zealand art history? It was a postscript. Nelson didn’t provide the conditions for those people to become artists; it provided the conditions for them to be menial workers and to struggle.”

White’s take on her new home mixes fondness and frustration—befitting a town with a split personality. She is sensitised to its lack of appreciation for things Maori. “Buddhism is very strong here; it infuriates me that at times people seem to know more about the politics of Tibet than they do about Maori.”

[Chapter Break]

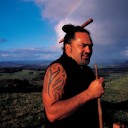

Bright art, pale town: in the last census, the Nelson region was New Zealand’s least ethnically diverse, with a population more than 80 per cent European. Yet despite Maori’s low demographic profile, corporate Maori is emerging as a heavyweight player in the region’s economy, alongside powerful families such as the Talleys and corporations such as Sealord.

Wakatu Incorporation’s concrete and steel downtown headquarters speaks of that power. The first thing you see is a monumental carving, a nine-metre-long, 3.5-tonne stylised waka, set on its end and rising three storeys through the atrium.

Wakatu’s wealth owes nothing to Treaty settlements. It’s not an iwi, but a corporation owned by 3000 descendants of the four tribes who sold the land on which the New Zealand Company established Nelson. Wakefield’s intention—again, unrealised—was that onetenth of that land would be set aside as reserves for Maori enrichment. It wasn’t until 1977 that “The Tenths” were signed back, and another decade before Wakatu secured the right to do anything more than administer it. The incorporation has made sharp progress since, turning $11 million into $250 million worth of assets, with a stake in Nelson’s major economic drivers—with the exception of forestry and tourism.

“When the Europeans arrived here, Maori were great traders,” says Keith Palmer, Wakatu’s Pakeha CEO, “and one of our major goals is to return Maori to that rightful place in the Nelson economy, so that’s why we’re in seafood, wine and horticulture.” (In property, too: Wakatu is a major developer and landlord.)

Palmer also notes that Nelson is one of New Zealand’s most export-focused economies, heavily reliant on primary industries, with lower-than-average wages and a big hole in the 20–35-year age group. Wakatu wants to change it all, and is focusing on selling high-value food and beverage products into Asia. It recently inked a deal with China’s biggest wine company, and wants to be a major player in aquaculture, particularly in high-return fin-fish farming. Most ambitiously, it is pursuing a multimillion-dollar centre for seafood and aquaculture at the Glenn, just north of the city, that could be a catalyst for a thriving export industry.

“Nelson is a natural centre for aquaculture,” says Palmer. “We have the Cawthron [research institute], the natural resources, Plant & Food, we’ve got the technology and infrastructure; it’s just a question of putting it together. We’re pushing it strongly, because we think that is where Nelson’s future lies. It’s a natural fit.”

Eight tribal proverbs translated into eight management principles cover a wall at Wakatu headquarters. Among them: “He who is active, thrives”. Nelson, sunbaked, self-content—a “Sleepy Hollow”—has always been a place where dreamers have to graft.