To Samoa, to war

Just over a week after Britain declared war on Germany, now 100 years ago, New Zealand entered the fray also, despatching troopships to take Samoa. It would be a benign introduction to the horror that would unfold in Europe and Africa, but the first step in New Zealand’s involvement in the Pacific, and the coming of age of a country.

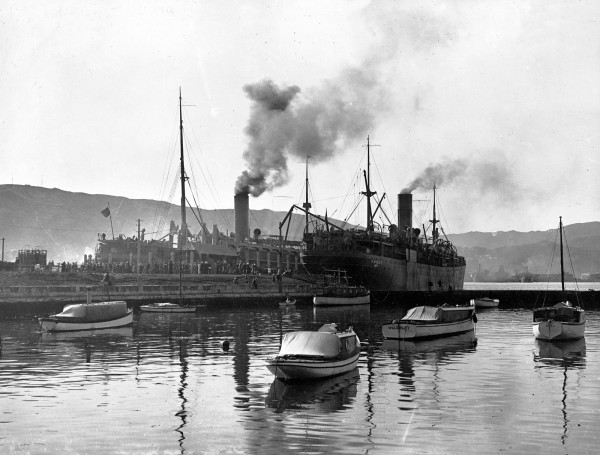

August 12, 1914 was only a few hours old when New Zealand offered up its first sons to the Great War. From the Buckle St drill hall in Wellington, they marched down Cuba St heralded by a brass band, cleaving a reverent crowd, to King’s Wharf, where the transports Moeraki and Monowai laid down gangplanks to glory.

It took most of the day for 1600 recruits to embark, against a backdrop of singing, haka, and what one observer called “merry raillery” from the wharfside crowds. One private almost became the first casualty of the war when he fell overboard.

Around 7pm, the transports loosed their ropes. Wives, mothers and sweethearts watched their men draw away; the ships turned and steamed towards Matiu/Somes Island, then promptly dropped anchor: the Admiralty had yet to deliver sailing orders. Moeraki and Monowai swung about in a wretched Wellington southerly all the next day, and the morning of the next, until the New Zealand Expeditionary Force ran out of porridge.

All talk aboard was of the destination, still unknown: the surf boats hinted at a tropical landing (and the skippers of both ships were old hands in the islands). But why, the men may have wondered, were they issued heavy woollen underwear and uniforms?

Toward the evening of the 15th, secret orders finally came to the hand of the commanding officer, Colonel Robert Logan: “You will proceed to the German islands of Samoa and seize them…you will take such measures as you may consider necessary to hold them, and to control the inhabitants.”

New Zealand had been given a job to do, but the British cable made it very clear that once the job was done, Samoa was to pass to the Empire. The cable sent to the Governor had been explicit: “If your ministers desire and feel themselves able to seize German wireless station at Samoa we should feel that this was a great and urgent Imperial service. You will realise, however, that any territory now occupied must at the conclusion of the war be at the disposal of the Imperial Government.”

Finally, the transports slipped anchor under a pale sliver of waning moon. Rounding Pencarrow, the vessels turned north, to a rendezvous with three British cruisers, Psyche, Pyramus and Philomel, as escort and protection against the German cruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, known to be prowling the western Pacific. The convoy, blacked out save for dim bow and stern lights, headed for New Caledonia, where they were joined by the French cruiser Montcalm and the Australian cruisers Australia and Melbourne.

Next port of call was Suva, where 14 Samoan men volunteered for the liberation of their homeland. They were welcomed aboard the Monowai by officers grateful for liaison and interpretation staff.

Not long after the ships left Suva, the mood on board turned sombre as bayonets were issued and sharpened and the men placed dog tags around their necks. What had so far been a bit of a lark had become a voyage more grave for the mostly rural volunteers as they stowed their 150 rounds of ammunition each.

The convoy now ploughed into heavy seas, and the landlubbers suffered: deck parades were abandoned and the sick musters were better attended than the church services. Worse still, the food was running low so that raw onions stolen from sacks aft—atop ship’s biscuits became something of a treat.

The fleet closed on the island of Upolu of August 29 in the early dawn from the south-east. Reveille roused the troops to a first glimpse of their objective. Psyche was to enter the port under a white flag, while Australia, Melbourne and Montcalm were to seal the transports in under a protective blockade to seaward. Nobody knew where the German cruisers were.

Ashore, by various guesses and scant intelligence, waited a force of some 80 Samoan armed police under German captaincy, but Logan was mindful that visiting German warships reported recently may have unloaded reinforcements and weapons. There were also between 300 and 400 German civilians on Upolu, who may have been conscripted into its defence.

The soldiers could now make out the sharp spine of the island. Plantations tumbled down the verdant flanks, and a belt of foaming white marked the thrashing of breakers on the fringing reef.

The German flag flew above the Government offices opposite Tivoli Wharf, where a New Zealand cutter tied up, bearing an ultimatum for the German Governor from Rear Admiral Sir George Patey, commander of the Allied fleet:

“Your Excellency,

I have the honour to inform you that I am off the Port of Apia, with an overwhelming force, and in order to avoid unnecessary bloodshed I will not open fire if you surrender immediately. I therefore summon you to surrender to me forthwith the town of Apia, and the Imperial possessions under your control.

An answer must be delivered within half-an-hour to the bearer. Wireless communications are to cease instantly or fire will be opened on the station. If no answer is received to this letter, or if the answer is in the negative, the cruisers have orders to cover the landing parties with their guns.”

But the German Governor, Erich Schultz, had already fled inland to the wireless station, and the troops spent a breathless hour waiting for news from the landing party. Another 30 minutes, and the Psyche lowered her white flag. The cruisers moved inshore and trained their guns. In the nick of time, signal flags fluttered a missive that no resistance would be offered, although, ran the German cable, the territory would not be surrendered. Schultz expressed umbrage at the threat of bombardment, claiming it contravened the Hague Convention. He also advised that the wireless station had been stood down.

As a picket boat swept the harbour for mines, the cutters were lowered, and soldiers of the first wave scrambled down rope ladders to the bucking craft. Each boat bore a company of infantrymen, a machine-gun section, field engineers, signallers and medical staff. They plied the reef entrance and stood to off the beach near Matautu Point while the soldiers waded ashore. Then the men regrouped on the road as the 5th Wellingtons combed surrounding bush.

By 12.30, the New Zealanders had established their beachhead.

They crossed the Vaisigano River and seized the courthouse, post office and telephone exchange, custom-house and other Government buildings. Anything of utility was commandeered—horses, bicycles, vehicles. Naval signallers began tapping their codes; Samoa had been invaded without a shot being fired.

It fell to Captain Keenan and his 3rd Aucklands to secure the prize—the wireless station. Following their Samoan guide, the company struggled under heavy packs to their steep objective. Their thick woollen clothing was a sweaty liability, and some men had to be left beside the track. The detail arrived at the station (completed only weeks before) around midnight. The station guard put up no fight, but it became clear the Germans had sabotaged the plant, removing engine governors and reconfiguring the electrical circuits into a maze of bad connections.

Then a radio operator noticed some odd-looking wires running from the dynamo into a hole in the floor. Following the leads gingerly, he found himself face to face with a stack of dynamite: had they started the engines, the company would have been blown sky-high.

Later the next day, Governor Schultz was put aboard a transport bound for New Zealand and spared the sight of the Union Jack (at the insistence of the British) being hoisted over the courthouse as the Psyche loosed her guns in celebration.

The liberation was complete. But its effect rather depended on which side you were on.

For many Samoans, the New Zealand occupation would prove more oppressive than the German. The next five decades were destined to be some of the most inglorious in the country’s history.

For New Zealanders, the moment was also bitter-sweet. The annexation fulfilled a long-anticipated desire for power and colonial-style influence in the Pacific, and it would mark the first volley of the country’s participation in the Great War, a conflict unlike anything the world had witnessed before. Regrettably, other theatres of combat would not be so benign as Samoa. New Zealand landed on the beach in Apia as the ready and willing pawns of the Empire, but landing on another beach on the Gallipoli Peninsula less than a year later, the small nation would fully appreciate the cost of its allegiance.

One hundred thousand New Zealanders served overseas—ten per cent of the population—and nearly one in five of them perished. Those fortunate enough to return (among them, 40,000 wounded) came back older and wiser, with a new understanding of New Zealand’s role in global affairs, and the many aspects of culture and identity that set it apart from Mother England. These would be hard lessons to learn, and the first step of that journey was the stride from a navy cutter onto the shimmering sands of Samoa.