The unseen world

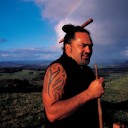

We shake hands. I say, “Kia ora,” you say, “Kia ora,” and, unless you’re Maori or we are in a Maori setting, this is usually followed by a conscious effort on my part to contain the urge to press noses with you.

For a Maori, the hongi is a physical expression of our meeting on a spiritual level. My wairua (spiritual self) greets yours.

The hongi is the key to a free flow of emotions based on mutual trust and goodwill. The breath of life enters and leaves through the nose. The practice of hongi with the deceased at a tangi is a physical acknowledgement that the wairua has indeed departed its mortal coil — the nose being the final part of the body to turn cold.

But, back to you and me, the Maori in me says, “Go ahead,” but somehow the conventions and the times in which we live dictate something else. There is an uneasiness. I see it in your eyes, I feel it in your hand — your wairua and mine do not sit comfortably together. We have merely acknowledged each other’s presence.

Even after 150 years we still choose merely to co-exist.

Come, feel the warmth of my nose.

They ring me at quarter to five on the morning the old man [Sir James Henare, paramount chief of the northern tribes] died.

Afterwards I sat for a while thinking about the old man. Then I rang a friend at Mitimiti.

“Harold, I can see the mullet jumping in the waves,” I said.

“No, Father, no mullet. The fishing’s bad at the moment.”

“But Harold, I want some mullet to take to the old man’s tangi. A koha (gift) from our people.”

“Well, Father, if you want me to go out, I will. But I don’t think there’ll be any fish for the tangi.”

Harold rang back later that morning. He had ten dozen mullet.

I say that was the old man’s mana.

Mana is not just charisma. It is a force that brings about change; an ability to act in ways that move people. Mana isn’t something you can set out to earn or achieve, like ‘Brownie points’. It comes from a lifetime of experiencing and addressing the unseen world of tapu.

Tapu means far more to the Maori than just prohibitions (“Don’t touch this”, “Don’t go there”). Tapu is the spiritual essence of all things. It arises from the mauri, the life principle of all creation, and constantly points us back to the source: Io, or God.

Trees have tapu, so you don’t cut them down without acknowledging Tane, the guardian of the forests. Rocks and mountains have tapu; Tongariro, for instance, is so tapu that some Maori will not even look at it. Fish and birds have tapu, and it is common practice for fishermen to return the first of their catch to Tangaroa, guardian of the sea.The highest expression of tapu, though, is in people.

Te wa, the journey of life, is filled with opportunities to address the tapu of our fellow-travellers. This is done by acknowledging their dignity as human beings created by God. At one level, the words “Kia oral” (literally, “Have life!”) are just a common greeting; at a deeper level they are an acknowledgement of the worth of another person. By greeting someone you are addressing their tapu.

A very visible and moving way of experiencing tapu is in the tangi; hence the importance of these occasions to Maori people. I have ministered for 12 years in and around my home marae of Motuti, a remote settlement near Panguru, on the north Hokianga. In just one of those years I buried 44 people, two-thirds of whom were from towns and cities away from the Hokianga.

Why do the families of such people return to the ‘back of beyond’ in droves for a tangi? Because it is a way of acknowledging the dignity of the person who has died, and the dignity of their ancestors and the whole whanau. And by returning to the source of tapu, the family and friends are invigorated and spiritually replenished.

I liken it to te kawai kumara (the runners of the kumara) coming back to te putake (the tap root). Cut off from the root, the runner shrivels. It can only take in food by joining itself to the root.

The process of welcoming visitors on to a marae is another well known way of addressing tapu. Visitors (manuhiri) are under tapu in the form of a prohibition as they approach a marae. They have their own tapu, or dignity, of course, but in this context they are foreigners, an unknown quantity. Who can tell whether they are friend or foe?

The kuia calls her greeting. In some situations a warrior issues a fiery challenge and lays down the wero, dart. The visitors respond according to the protocol of the marae with korero (speech) and waiata (song), after which the hongi (embrace) lifts the tapu, erasing the status of `manuhiri’ and making the visitors one with the tangata whenua — the people whose turangawaewae (identity) is at that marae. The visitors are now hunga kainga (people of the house).They share their hosts’ hospitality, protection and mana.

In traditional Maori terms, ignoring the principles of tapu is the same as declaring spiritual suicide. Yet a society that favours material over spiritual values has systematically violated and belittled these beliefs, labelling them superstitions and relics of paganism, and declaring them to be of no importance in the modern world.

The reality is this: a failure to address tapu is a failure to grow. Your mana remains stunted, moments of achievement slip through your fingers and your life journey becomes frustrating. Not only that, if you fail to respond to the challenge of te wa to address tapu, you are not just depriving yourself of mana, you inhibit the growth of others. Life is a team sport; if you drop the ball you let the whole side down.

The relationship between mana and tapu can be compared to the workings of an artesian well. The water source deep underground is like tapu; the gushing of water up through the bore and on to a thirsty land is like mana. Failure to address tapu drives the water back down the bore, and the land dries up.

There are three ways of addressing tapu: through tika (justice), pono (integrity, or faithfulness to tika) and aroha (love). By continually striving to act with tika, pono and aroha in day-to-day life, tapu flourishes and mana radiates outward like the ripples of a stone dropped into a pond.

Consider the laws of tapu as they relate to food. In Maori tradition the preparation and consumption of food must be kept separate from any object that has to do with the body, such as a bed, a toilet, etc. Even to sit on a kitchen table where food is prepared would violate tapu. Yet these values are largely lost on younger Maori who have grown up with the prevailing Pakeha culture which makes no distinction.

I have been involved in two instances where the tapu relating to new life and the body has been dramatically violated by association with food. Both related to the practice of Maori mothers asking to retain the afterbirth for later burial (an important ritual which fixes a person’s roots to his tribal area). In both cases the placenta had been put in a household deep-freeze full of food until the mother came out of hospital.

It would be no exaggeration to say that, in terms of tapu, all hell broke loose! A family member became violently ill in one case and the mother became uncontrollably hysterical in the other. In both cases I insisted that the afterbirth and all the food be immediately buried, and as soon as this was done the physical problems ceased.

Nowhere has the erosion of tapu been more devastating than in the loss of the Maori language. Language is tapu because it expresses the very soul of a person. Without te reo, tapu is stifled. Without te reo, the karakia (prayers) that fertilise and enrich every aspect of life, from the cradle to the grave, are impotent. Within Maoridom there are prayers for birth, prayers for betrothal, prayers for carving canoes, prayers for baiting a hook, prayers for planting, weeding, reaping, chopping and a thousand other activities.

If tapu is the water source, and mana the gushing of the well, then te reo is the bore which allows mana its expression. The quenching of language is a severe violation of tapu; it blocks the puna waiora, springs of life.

Violations of tapu demand to be re-addressed through tika, pono and aroha. But an essential part of healing and reconciliation is encounter — preferably in person, or at least through the iwi (tribe). This is because violation of tapu is not solely an individual matter; it affects the whanau and the iwi.

Here is one reason why some Maori are seeking an alternative justice system, one that involves the extended family and tribe, and one which gives scope for encounter. Without acknowledgement and encounter, injustice will never be truly resolved. Like a whale, it will disappear for a time, only to surface again seeking the pure oxygen of tika, pono and aroha.

A hundred and fifty years ago the Treaty of Waitangi provided Pakeha with the opportunity to become tangata whenua, and to share the mana of the Maori. Like visitors to a marae, the newcomers were seen as manuhiri. The treaty was a vehicle by which the designation of manuhiri could be lifted. However, though the document was signed, the treaty was not implemented. Tika and pono were violated, and aroha fled.

I believe that Pakeha have not enjoyed the mana of tangata whenua because of treaty violations. The result is a generation of New Zealanders that is still looking for its roots and hungering for a deeper relation ship with the land.

The answer is in the tapu of the treaty. Address the tapu that has been violated, and mana will be set free to be the mantle under which all may become tangata whenua.

Only then will Hobson’s hopeful words become reality: “He iwi tahi tatou.” Now we are one people.