The tree hunters

Out there in forest reserves, down remote back roads and tucked away in corners of small towns hide giant tōtara, mataī and rimu. A tiny group of obsessive people, guided by old records and half-remembered stories, regularly hit the road in search of these monsters. Their aim: to bag a champion tree, one whose size, age and majesty will put it at the top of New Zealand’s notable tree register.

It all starts in a Dunedin pizza joint. I’m waiting for my order, idly scrolling Facebook on my phone, when I stumble on a page called Great Trees of New Zealand. Most of the posts are from a bloke called Phil Barker, and his latest shows a man standing in front of an enormous, gnarled tree trunk, deep in the West Coast’s primordial forest. “Largest known matai in NZ,” Phil’s written. “8.76 m girth Lake Kaniere. Discovered last year by my twin Kev and his friends Keith and Claire. Extremely old I believe around 2000 years.”

I’m intrigued. Surely the biggest, oldest, most spectacular trees in New Zealand were all identified long ago?

I immediately message Phil to find out more.

“Yeah mate into hunting giant podocarps,” he replies. “We’ve found record-breaking rimu matai and kahikatea on the coast. I’ll send a few pictures. Planning on checking out a new spot this week. Have enough leads to search for weeks. Make that months.”

By the time my pizza is ready, I have a slew of big-tree photographs in my inbox and a new story idea brewing.

[Chapter Break]

Two months later, photographer Neil Silverwood and I are trundling along a gravel road in my Ford Mondeo, skirting Kōtuku Moana/Lake Brunner, near Greymouth. Leaving behind dairy pastures, the road plunges into dark, thick podocarp forest, the sky quickly obscured by the towering trees on both sides.

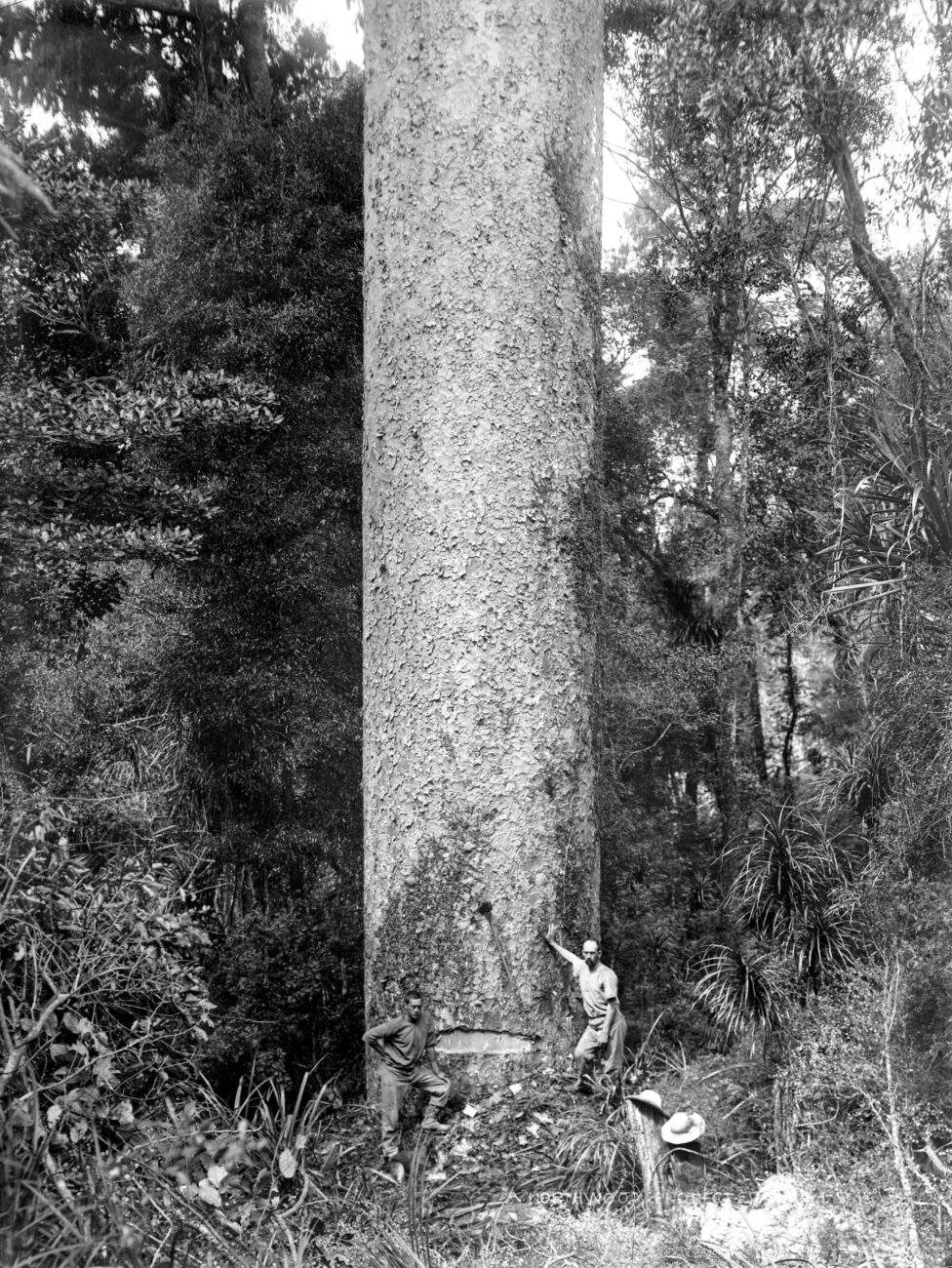

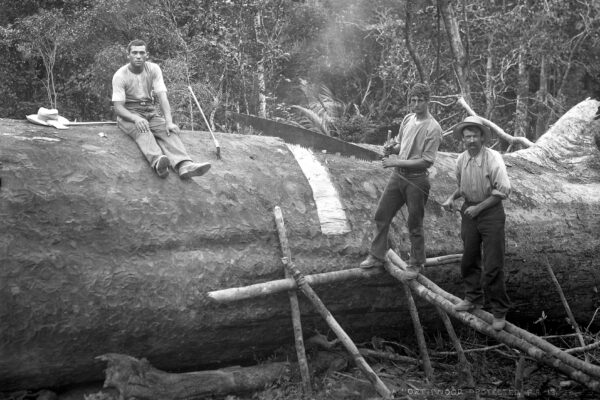

Much of New Zealand’s lowlands were once dominated by forests filled with kahikatea, rimu, mataī, miro and tōtara, but commercial logging throughout the 19th and 20th centuries laid waste to them. It came to an end only in the 1990s, largely through fierce opposition from activists, and just in time to save the last few precious fragments—like this small reserve on the shore of Lake Brunner. Some of the biggest native trees still standing in New Zealand wait just off the road—not that you’d really know that as a casual visitor. According to the sign, there’s nothing here besides a short track that leads to a waterfall.

When Neil and I pull up at the car park, Phil is already there, along with his friend Glen Johnston, a forester turned conservationist. Phil runs a motel in Hokitika, and he’s a busy family man and whitebaiter. Any chance he gets, though, he’s on the road, hunting the last of the Coast’s big podocarps. Back in 2019, not far from where we’re standing, he found New Zealand’s biggest kahikatea. Today, he’s looking for another giant he’s spotted in a satellite picture of the reserve.

The forest is tangled and wiry. A web of supplejack vine ensnares the trunks and tree ferns and podocarps, making for very difficult passage. We tumble through the undergrowth, contorting our bodies to avoid the supplejack’s grip.

A former rugby league prop with a bad knee, Phil is not exactly built for this kind of travel. “It’s never a straight line,” he says, puffing. “You see a big tree and make your way towards it, and it’s almost like it moves on you as you go through the bush.”

As we get closer, the tree’s crown looms through gaps in the canopy. Even from a distance, you physically feel its presence, its size seeming to generate a kind of gravity.

Its base, when we reach it, is cluttered with vines, and its heights are full of perching plants—ferns, lilies and creepers. At first, Phil’s not sure if it’s a miro, mataī or a kahikatea. He eventually decides it’s a mataī—impressive, but not big enough to bother measuring. Then Glen finds some fallen foliage, and it turns out to be a miro, the smaller cousin of the mataī. This changes things.

“That’s an exceptional miro,” says Phil. “We’d better throw the tape around that one.”

[sidebar-1]

With Glen’s help, he wraps the tape around the trunk at chest height. Then he whips out his Nikon Forestry Pro—a range-finding device that measures the height of trees using a laser beam—and steps back to get an angle on the top of the trunk.

“Shit, it’s a bloody beauty!” he shouts. “Twenty-seven metres. I’ve looked at hundreds of miro and this is the largest I’ve ever found. This’ll be a record tree.”

I’m finding it hard to comprehend. We’ve scrambled just a few hundred metres into roadside bush and found the biggest miro known in New Zealand.

“Off to a good start, lads,” says Phil. “It’ll be on the tree register in a few days.”

[Chapter Break]

The New Zealand Tree Register uses a point system to rank trees, with girth, height and average spread determining the final score.

Top of the register is Te Matua Ngahere, the 2000-year-old kauri in Northland’s Waipoua Forest, with 807 points. Its neighbour, Tāne Mahuta, comes in second with 788 points. (Although taller than Te Matua Ngahere, Tāne Mahuta’s girth is lesser.)

The register began in the 1970s, when the Royal New Zealand Institute of Horticulture created a database of notable trees. Today, it’s maintained by a group of enthusiasts, one of whom is Brad Cadwallader. An arborist in Nelson, Cadwallader spends his spare time hunting trees—particularly exotic specimens such as elms, sequoias and macrocarpas, which can be found all around New Zealand. For him, digging up the stories attached to these old trees is a big part of the appeal.

“It’s a real hobby,” he tells me. “When I go travelling, I take my measuring gear with me, and I enjoy nothing better than to go out poking around in the bush or in people’s neighbourhoods, seeking out some of these stories.”

Stories like that of the Seymour Oak. In 1842, Henry Seymour, one of the first British settlers in Nelson, planted acorns he’d brought with him. One of the seedlings washed away in a flood, but was eventually found and replanted where it stands today, on Seymour Avenue.

The top 25 trees on the register are all kauri or introduced species, such as eucalypts and redwoods. (The biggest redwood is a 150-year-old tree in the Frankton Recreation Reserve in Queenstown, and the biggest eucalypt is on the Taieri Plains near Outram.)

[sidebar-2]

“We’ve got a very large number of species in New Zealand that are the largest in the world,” says Cadwallader, “because we’ve got a very long growing season and a temperate environment. In Tauranga is the tallest macrocarpa in the world at 52 metres. We’ve got the largest Camperdown elms and horizontal elms. We’ve got the largest and the tallest Norfolk Island pines in the world. The list just goes on and on.”

Giant native trees are usually in less accessible spots than introduced species, meaning there are likely many yet to be recorded.

“There’s hidden champions out there to be found,” says Cadwallader. “I get contacted every day about a big tree that someone has heard of, or that a hunter has seen somewhere. There’s not enough time in the day. Maybe when I retire, I’ll have more time to be able to go and actually pursue some of these trees.”

[Chapter Break]

Phil, Glen, Neil and I push deeper into the bush around Lake Brunner. I’m starting to sweat as we battle the undergrowth. Phil is leading us towards a huge tree he spotted on Google Earth—one of his most valuable tree-hunting tools. With Google Earth, he can scan detailed satellite images of the forest and locate the biggest tree crowns before going in for a closer look.

As we come up on it, the enormous mataī seems to disappear into the sky above. A rātā vine winds around it. Phil gets his tape measure out to check its girth, having to clamber over fallen logs to do so.

“Shit, it’s well over two metres!” he yells. “We better register this one. This is a real big tree. It’ll have to be a thousand years old.”

He pulls out his phone and records a video for the Facebook page. “We’ll register this and hopefully people will come and see it.”

Mataī are his favourite tree. “It’s just the majesty of them,” he says. “You’re looking at something that was around before people came to New Zealand. Most of the farmland on the West Coast was once mataī forest, because mataī likes the flat, fertile ground. Luckily we have some areas left, but it’s only a few per cent of what there was.”

In 2019, near Lake Kaniere, Phil located the biggest known mataī, with a register score of 407. Then his twin brother, Kevin, a science teacher, came down from Auckland to visit, and went looking for the record-breaking tree.

“When your twin brother gets into something, you often get roped in as well,” Kevin tells me later over the phone. “I’m just in awe when I’m around these big trees. It’s a spiritual experience. They’re just magnificent.”

Kevin didn’t find the mataī. Instead, he stumbled across a different, larger tree, one with a score of 441—a new national record.

The same year, Phil was tipped off about a stand of big rimu trees near Harihari. He found among them a 35-metre giant that turned out to be the biggest known rimu in New Zealand—449 points.

“Phil published some photos online,” says Kevin, “and then this guy sent a picture of what looked like another enormous rimu. It was in the Otanewainuku Forest, near Tauranga. So my wife, Olga, and I took off for a day trip. We spent about four or five hours in the bush and found about a dozen really big rimu trees.”

It was only as they were preparing to leave, however, that Kevin and Olga stumbled on their own record-breaker, toppling Phil’s Harihari record by 26 points.

“Phil was a bit put out.” Kevin laughs.

“There is an element of competition, because we’re bloody blokes and it’s a bit of a laugh. But really, I don’t care. I’d love someone else to go and find a bigger one.”

When I ask Phil about it, he’s philosophical about his brother claiming his record—and with a North Island tree at that. “We’ll just have to keep looking and see if we can beat it,” he tells me.

The enormous fallen mataī Phil’s led us to today would have, he says, been the biggest recorded if it were still standing. Its upended base is a gnarl of twisted roots, one clutching an enormous granite boulder it ripped from the earth as it fell during Cyclone Ita in 2014.

Since Ita, there has been a push from milling companies to be allowed to extract and mill fallen logs like this. A reasonable-sized mataī might hold more than $25,000 worth of timber. I ask Phil how long this log will last here on the forest floor.

[sidebar-3]

“Centuries,” he replies. As it decomposes, it will provide a food source and home for fungi and billions of invertebrates, as the nutrients in its wood leach slowly back into the soil, nourishing the forest that lives on above it.

But Phil already has his eyes on another huge mataī. He thinks he may have located a tree on Google Earth that matches the description of one recorded in the Waitaha Valley by the legendary explorer Charlie Douglas, and marked on a Lands and Survey map in 1906.

So much to discover, so little time.

The day is wearing on and Phil is in no mood to sit around.

“I can see another big bastard through there,” he says now, peering through the foliage at another looming crown. “It’s a rimu. I think we should press on.”

[Chapter Break]

I leave the West Coast with big trees haunting my thoughts. After my first day tree-hunting, I went and looked up Phil’s Nikon Forestry Pro rangefinder online. It was $650. This worried me—the last thing I need is another hobby.

State Highway 73 leads me out of the remnant podocarps of the lowlands, through the beech forest of the higher altitudes, then over Arthur’s Pass and into the open tussock country of the foothills. From here, the road drops to the intensively farmed patchwork of the Canterbury Plains.

What has been lost here on the east coast of the South Island is hard to comprehend. All but minuscule traces have vanished. What’s left are like crumbs on a smooth tablecloth.

One of these crumbs is nestled in the foothills of Mount Peel, near Geraldine. Here I take the Dennistoun Bush Track through a tiny patch of old podocarp forest, and get a glimpse of the irretrievable past.

In the dappled golden light of early evening, I follow the path through groves of big kahikatea and mataī. This is no wilderness experience—in the distance I can hear roosters crowing and what sounds like a lawnmower. At the edge of the water race, I find the tree I came to see.

It’s known as the Blandswood tōtara, after the nearby village of the same name. Twenty-one metres high and with a girth of 11 metres, it’s the second biggest tōtara in the country. Its gnarled, thick base looks like the fist of God punching the earth. The soil around it writhes with roots. This is not a tree you visit. It’s one you humble yourself before.

There is no information panel or signpost to tell visitors what they’re looking at, or to explain the huge loss it represents. I only know it is here because it caught my eye while perusing the New Zealand Tree Register yesterday.

I pay my respects, then get in my car and drive off across the manicured, tamed landscape of rural New Zealand, shelter belts of macrocarpa and radiata pines arrayed over the bones of our long-vanished forest.

I went through the mountains to write about tree-hunters, and I’ve returned as one of them. From now on, my eyes seek out big trees, my mind fizzing with questions: How big? How old? What story do they tell?