The Sound Barrier

Classical composition arose in New Zealand during the 20th Century—a period when music was undergoing its global post-romantic revolution. Since that time, Kiwi composition has gone from strength to strength.

A feather-light snow descended in languid spirals, alighting on woollen hats and hunched shoulders, dissolving on contact with worn cobbles. The sun had set at 4 p.m. and the city was washed in the spectral glow of street lamps. Glimpsed through iron gates, the graveyard flanking Greyfriars Kirk appeared to have been lifted from a Christmas card, pyramids of snow topping all the horizontal ledges.

Situated at the top of Candlemaker Row in Edinburgh’s Old Town, Greyfriars, with its long and venerable history, seemed an ironic institution to be hosting an alien invasion. It was the venue for a festival entitled New Zealand, New Music, a week-long gig on the Scottish stage for Kiwi composers. Kenneth Young, a regular conductor–performer with the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra and an accomplished composer in his own right, was holding the baton for the impressive BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra.

Chatting with Ken earlier in the week, I’d been struck by the realisation that I’d never actually attended an orchestral concert in New Zealand dedicated specifically to New Zealand music. Certainly I’d been to many NZSO and Auckland Philharmonia concerts that had managed to squeeze in a local work, but Kiwi compositions often fly under the radar, sandwiched into programmes celebrating the works of long-dead Europeans. Only now, this winter’s night in this corner of old Europe, was I to experience such a rare delight.

[Chapter Break]

Beneath large stained-glass windows set within heavy stone arches, penguin-suited musicians tuned their instruments. The distinctive noise an orchestra makes prior to performance is something I find strangely compelling. Every team-musician becomes an individual, tightening or easing strings, checking reeds, fingering difficult solo passages and organising page turns. From this pre-flight checklist, the receptive listener can sometimes glimpse the entire programme, albeit chopped into fragments that thrust and parry, a melting pot of unexpected liaisons.

The same pre-concert ritual can also be viewed as a sort of passport stamp at the start of a journey. To audiences of the classical repertoire, its burst of sound presages a tour through familiar and much-loved terrain. But for audiences of works by living composers, it usually heralds a foray into uncharted waters. The maps used by ancient mariners were bordered with dragons and tempests to indicate the limits of knowledge, but those same seafarers also told stories of fabled lands with jewel-encrusted streets and lakes of ambrosia. Anything might exist beyond the horizon.

The concert began. First off, a piece by prominent English composer Edward Harper, Intrada after Monteverdi, which was delivered in the spirit of a Scottish welcome-cum-challenge, a kilted haka. Toying with Monteverdi’s famous theme, Harper made an unequivocal statement: You Kiwis are playing with the big boys now, playing our game on our field—we invented this music!

I could feel some collective adrenalin in the Kiwi contingent around me, a buzz of nerves, excitement, possibly even uncertainty. This was to be a telling exposure for a group of our leading composers—antipodean upstarts under the critical scrutiny of an informed international audience. How would they fare? Would they cut the mustard?

With the opening bars of Gillian Whitehead’s Resurgences came an exhalation of relief. As the first Kiwi respondent, this work was smart programming. It is an unimpeachable masterpiece. Shot through with flickering motifs that weave around a darker undercurrent, Resurgences contrasts a delicate touch with searing intensity. The BBCSSO, which specialises in new music, was clearly in its element.

Then came Jack Body’s seductive Melodies for Orchestra, a score based on transcriptions of folk and street music from Greece, Indonesia and India. Pulsating with energy and imbued with exotic Eastern motifs, Melodies is another classic work. As it hurtled to a climax, I felt my feet tapping, my breath shortening. It’s hard to communicate how exciting an orchestra going full tilt with a dynamic work can be to anyone who has not experienced it first-hand.

After the intermission, the momentum was given a further boost by Helen Bowater’s ebullient New Year Fanfare, another window to the East. Bowater lifted her sound world for this piece from street celebrations she had joined in Yogyakarta. The Javanese take to the streets with paper hooters and whistles to welcome the change of the year in a riot of colour and sound, and the old church reverberated with their transmogrified enthusiasm.

Lyell Cresswell’s Salm then launched us into a soundscape more familiar to many in the audience. A Wellingtonian, Cresswell has been based in Edinburgh for 30 years and was the principal architect of the festival. Salm is a piece that evolves from a lonely invocation, in which cello supplants voice in a system of Gaelic psalm-singing. With this archaic style of church music, a precentor leads his congregation, who, joining in piecemeal with heterophonic variations on his theme, weave their voices in and out as they build to an exultant climax. Salm is a beautiful work, complex, rooted in tradition, yet decidedly contemporary. From the opening few bars I found myself again on the edge of my seat.

Rounding the evening off was a newly commissioned piece, the high-octane Seikilos by John Psathas. Building on an epitaph from a second-century Greek gravestone—a reminder to enjoy life in its “sweet fleeting”—Psathas added yet another ethnic strand to the international flavour of the concert.

It came as a shock to plunge back into the chilly embrace of a northern winter, my head ringing with music from warmer latitudes. Are New Zealanders really an amalgam of all these diverse cultural influences? Sure, they treat overseas travel like a birthright, but this pot-pourri of influences could have been the music from planet Earth that NASA would stick in a probe and fire off at alien worlds. You could almost taste the alternating fragrances of hibiscus, lemongrass and retsina wafting insolently about those Celtic flagstones and recesses. A great tonic for a Scottish winter, but where were Fred Dagg, No. 8 wire, the All Blacks and the haka?

Of course, with such a high calibre of music, the presence or absence—or my inability to detect—a Kiwi accent was merely intriguing. The message being spelt out on this cold night was pointed: Vikings and other invaders of the British Isles are old history. Here come the Kiwis!

[Chapter Break]

Sitting with composers at rehearsals—watching them flinch and grimace during the playing of their own work, react with delight at things too subtle for my ear, or smile enigmatically through the creations of their colleagues—I feel like an impostor.

It isn’t that I don’t appreciate their product. I do. What is strange, and what confounds me, is their approach to music, an enterprise that you might think holds few remaining mysteries. They listen to sound with different ears, speak to each other and through their music in a different language. Whereas we ordinary mortals tune in to melody, pulse, harmony and lyrics, and use music to facilitate or augment our mood, composers tune in to invention.

They create sonic textures, sculpting their sounds into melodic contours. They specify odd turnings and use strange metres or complex polyrhythms with an overriding view of music more akin to architecture or abstract art. They get excited about raw sound sources and ethno-musicological obscurities. They like to put glass and bolts inside expensive grand pianos because of the way junk resonates on the strings or changes the instrument’s timbre. They ask accomplished musicians to play on parts of their instruments that were not designed to be played—on the wrong side of the bridge of a stringed instrument or inside a piano—or to modify their technique to invoke overtones and other strange effects on woodwind and brass.

Subversive thinking is par for the course among artists, but few in other media seem as irreverent in their attitude towards their tools. How many movie-makers, for example, deconstruct their cameras? How many painters mutilate their brushes before starting a canvas?

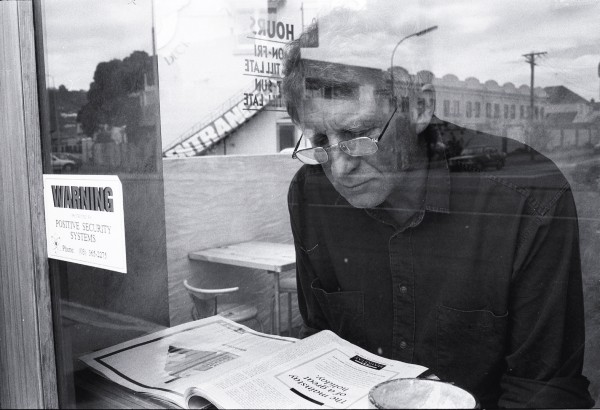

Even more perplexing is that, for a bunch of artistic deviants, composers look rather ordinary. Unlike the self-tagging of goth, punk, country or rap musicians, there is no clue in a composer’s general appearance to their strange passion. No black uniform, face paint, video gimmickry or bling jewellery. No headlining drug excesses or hotel-wrecking sex orgies. Composers walk past you in the street and they don’t register. Any one of them could be your kind aunt or industrious bespectacled nephew.

Yet the scariest death-metal rocker is musically dull by comparison, imprisoned by ultra-conservative 4/4 time signatures, their sharpest tools impoverished chord changes and dinky rhyming word-patterns. Drab-looking composers, on the other hand, can produce art so radical and anarchic it beggars belief. To them, the edgy stage antics of hard rockers who smash guitars into amplifiers, with all that unpredictable feedback, are little more than crude testosteronal theatre. They might be interesting for their sonic possibilities, but you can bet a composer would explore those possibilities far more inventively than any Pete Townshend or John Entwistle.

Even when framed in a conservative language, the creations of contemporary composers are complex and not for the faint-hearted. As one who dabbles occasionally in rock music, where a chord chart is an unusual indication of proprofessionalism, I am mesmerised by scores, especially orchestral scores. Concert musicians are not only told what to play and when to play it, they are also instructed how loud to play, what mood to approach a note with, and how much expression to draw from it.

An orchestral score contains instruction sets for 90-odd musicians to play parts written specifically for their instruments. All of which means a lot of notation, perhaps a hundred A3 pages of dense scoring for a mere 10 minutes’ playing time.

On completion, a score is entrusted to players or a conductor to interpret. The performance that follows is entirely dependent on the skill and empathy of their interpretation. I can think of no other artistic format, save perhaps script-writing, in which the creator takes such a large risk with the presentation of their art.

A composer knows absolutely what all the different parts playing together should sound like without hearing a performance of the work, because the score is constructed on an inner template. I have witnessed a look of horror in the eyes of a composer at a rehearsal when a single instrument in the great orchestral wash has been played p (softly) instead of pp (very softly) as specifically indicated. Welcome to Planet Nuance, the home of control freaks—somewhere beyond the asteroid belt!

[Chapter Break]

Lyell Cresswell left New Zealand in 1972 to complete musical studies in Aberdeen. Not wanting to take up an academic post and with more opportunities in Britain for freelance composing, he became established there without any real intention. It was an accidental migration—and serendipity for the Scottish arts community, which embraces him now as a national treasure.

I had my first exposure to his work at the 1987 Wellington Sonic Circus, an extravaganza of New Zealand music orchestrated by Jack Body. Cresswell had journeyed home to present part of A Modern Ecstasy, a large-scale work for orchestra. Some friends told me not to miss this piece, so I dutifully filed into the Michael Fowler Centre to see why there was such a buzz. I watched and listened and felt truly perplexed. A Modern Ecstasy sounded like the work of a master! It seemed so accomplished, challenging, and so very musical—why had I not heard of Cresswell before? He walked shyly onto the stage to accept the excited applause, a smallish man in his forties, balding and with thick glasses—someone’s Uncle Lyell in a cardigan—who had just tamed a huge beast of an orchestra with a work of daring originality.

But Cresswell thinks there’s more to it than that. Any new composition, by definition, has no precedent—no famous recording or historic performance to be compared with. A combination of a demanding score and a tight rehearsal schedule can lead to a fine work sounding like a shambles, with the result that the audience—unfamiliar with it—will assume the fault lies in the piece. A safety-first approach is therefore prudent. Invention and risk-taking are easier to flirt with as you move up the food chain, because the virtuosity of the players you work with increases.

I think you could also say that you’re not influenced by fashions to the same degree when you’re older,” says Cresswell. “You have more confidence to take risks.

One of his recent projects was a major commission from the Scottish Arts Council—a work of music theatre that explores issues of exile and identity. A subject of this work, Norman McLeod, was the fiery 19th-century Scots preacher whose exile with a band of followers, the Normanites, brought him to Waipu, south of Whangarei.

Exile is a theme that crops up regularly for Cresswell. Coming to terms with his own sense of uprooted national identity led him to the concept of a Kiwi music festival in Scotland. He wanted to show his adopted community that he was just the visible tip of an iceberg and that an exciting hub of art-music has flourished away from its European birthplace. His belief that the excitement and freshness of New Zealand composition would win over an arts-savvy European audience gave the project its momentum.

The Scottish press, lavish in its praise of the concerts, mooted that New Zealanders must be “natural multi-culturalists”, alluding to the way their composers move so easily through a sea of cultural influences. It’s hard to disagree with this assessment, but this and a second festival three years later included works that could only have grown out of New Zealand soil. Two were even based on New Zealand birdsong: Eve de Castro-Robinson’s haunting Other Echoes, and Gillian Whitehead’s Journey of Matuku Moana, which also explored the composer’s tipuna.

A number of composers, including Whitehead, Jenny McLeod and Helen Fisher, have identified strongly with Maori, collaborating with indigenous performers, artists and writers. Quite a few have been attracted to native birdsong, too. The distinctive kokako finds its voice translated in pieces by Douglas Lilburn, John Rimmer and Ross Harris, to name but a few, and many works evoke a range of voices from the dawn chorus.

New Zealand composers have turned to other aspects of their physical surroundings, too, for stimulus, infusing their music with the same vision of landscape that informed painters like Colin McCahon. Yet where a landscape falls most conspicuously on the eye, so does visual art. Translating sight into sound, on the other hand, is an abstract process resulting in something impressionistic at best. The hills of New Zealand rendered as music might easily merge into hills elsewhere. Lilburn’s Overture: Aotearoa—an iconic New Zealand work—could be enjoyed by someone not familiar with the specific landscape the composer had in mind as an evocation of, say, Sibelius’ Finland.

In other words, drawing inspiration from the New Zealand environment does not guarantee a distinctive Kiwi voice. It is also worth noting that New Zealand still doesn’t have a full generation of dead composers.

Douglas Lilburn, who holds the mantle of “Father of New Zealand Composition”, died in 2001. Edwin Carr, Lilburn’s contemporary, died in 2003, and was still writing music at the start of the century. Another composer of that generation, David Farquhar, is still writing substantial works. New Zealand music is a mingling of its first few generations, very much in its infancy.

While such a lack of historic depth could be viewed as a handicap, it has an upside, albeit one probably better appreciated from abroad. In the established music centres of Europe, stylistic movements often hold sway, meaning many composers work within the confines of particular schools or trends, closely bound to—and constrained by—a living tradition. New Zealand composers, by comparison—and other composers around the Pacific rim—while informed by musical directions in Europe and the United States, do not seem to be tied to them to the same degree. The music they produce is ineffably different. To my ear it can sometimes seem less measured, but it is extremely varied and has a certain unmistakable vitality and virility.

[Chapter Break]

One kiwi composer who regularly looks towards Asia for inspiration is Jack Body. Like many other New Zealanders of his generation, Body went to Europe for “finishing”, attending institutions in Cologne and Utrecht, then for two years in the late 1970s lived in Java, a guest lecturer at the Indonesian Music Academy.

Body’s interest in Asia was first kindled during a journey he made on his way back to New Zealand in 1971. Seeing life and death so vividly played out in places like India and Afghanistan caused him to think deeply about his art, placing it in a social and political context.

These days Body, an associate professor at the NZ School of Music, is still an inveterate traveller. While his work interests extend over the widest possible musical gamut and spill over into visual art, it is his synthesis of Eastern and Western music that creates the most immediate impression.

In 1998 Body staged an opera, Alley, with librettist Geoff Chapple, to open the New Zealand International Arts Festival in Wellington. Rewi Alley is a folk hero to the Chinese, admired for his lifelong dedication in their country to the principles of peace and education. Alley’s response to the grinding poverty and hardship he encountered in Shanghai in the late 1920s—rolling up his sleeves and getting stuck in—is one New Zealanders think of as typically Kiwi. Body’s fascination with Asian cultures mirrors Alley’s in many ways. He says he is drawn by the profound cultural differences between Asia and New Zealand.

“Perhaps the emptiness we New Zealanders feel, the lack of a sense of identity, the insecurity about who or what we are, all this somehow assuaged by his (my/our) engagement with a culture and history so ancient and volatile and sure of itself…through this experience we learn who WE are—I believe Alley always thought of himself as a “real Kiwi”—he could certainly never be or become a Chinese!”

Asia is no longer merely a travel destination—it has come to us. In recent years, central Auckland has witnessed a steady transformation of facial features from predominantly European and Polynesian to largely oriental. And just as Japanese, Chinese, Koreans, Vietnamese and Indians today fill the country’s universities, Body foresees Asian perspectives assuming greater influence in the arts.

He has transcribed Asian folk music regularly for Western instruments. Transcription is the process of taking something you hear and turning it into a score. Reversing the normal flow of score to music is, he says, a fascinating way to approach composition: “Music just exists in time and space and passes before our ears—transcribing creates a text to understand it.

In his orchestral work Pulse, Body pushed his transcriptions further, exploring pulse as a concept in Eastern and Western music. Along with the difficult metre of a Papua New Guinea fire dance, he combined Beethoven, Berlioz and Stravinsky into a web of juxtapositions. Pulse examines the primitive power of pulse in classical music. For some listeners it becomes a game of spot the famous theme, but the work warrants concentrated listening beyond that.

Hearing it for the first time, I sensed something new and exciting, an artist stepping back from his art to open up an unexpected vista. Rather than listening to new music with old ears, it seemed as if I was being instructed how to listen to old music with new ears! And therein lies a hint of the magic that one finds in this type of music—accompanying the text are layers of subtext, wheels within wheels.

Transcription supplies Body with a rich vein of possibilities, but it is just one of many ways to approach composition. The traditional image of a Mozart-like figure poring over his score with quill in hand is valid, but this is by no means the only way of arriving at a finished work. Jenny McLeod pioneered tone clock theory in New Zealand, a system that, from a given entry point and within certain parameters, dictates tone sequences. Other composers have mooted magic squares, random numbers, obscure mathematical systems or even messy old intuition to make musical choices. Some composers write from the middle out or from the back to the front, or cut and paste blocks of material. There are a few who annotate an essentially improvised structure, even playing directly to score via computer, while others are notorious technophobes who employ copyists to clean up their scratchings so that they are legible to players.

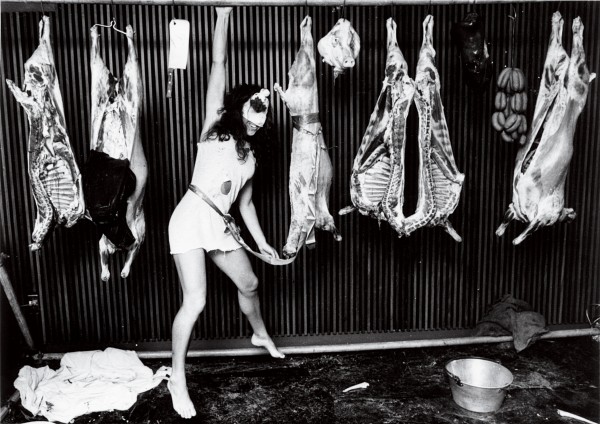

Then there are those who approach from a different angle entirely: rather than using notation, they manufacture the circumstances for an intriguing sound world to occur. Annea Lockwood’s 1960s work Piano Burning entails immolating an aging instrument to draw from it new sounds—an exploration of the boundary between creation and destruction.

Using a specific system does not necessarily dictate the way a piece finally sounds. For instance, a system that throws up melodic or rhythmic sequences still says little about how a work might be conceived or how it evolves. There are composers who see an overview of their work in visual terms, as shapes, colours or motion. Some explore a single motif or pattern, extrapolating all the material required for the work from this nucleus. Some approach composition as problem solving or, like Ross Harris, relate to music as a language which contains expectations of form and familiarity that are open to manipulation. By viewing it linguistically, Harris says, he can layer his composition “with mixed messages, illusions, false trails and almost never more than a hint of redemption”.

Despite the limitless variety of tools at the composer’s disposal, technical limitations impose some common constraints. While composers don’t need to be able to play all of the instruments they write for, they need to understand the properties of each: where its top and bottom notes sit; if there are any holes in the range, or intervals that are too difficult to span; how harmonics and other effects are produced; how fast a hand can travel around the frets or keys; and how much breath a musician can pour into a mouthpiece before going blue in the face. Even freeing up a hand to turn the page becomes a consideration in dense passages.

Yet, for all this, what is heard in the finished product seldom betrays the methods used by its author. At the heart of any piece is the same motivation as drives all art: a desire on the part of the artist to discover who they are and to find a way to express that tenuous insight in a tangible way.

[Chapter Break]

Chris Cree Brown is a Christchurch-based composer who has gained a reputation for pushing all kinds of boundaries. He has occasionally stirred up audience reaction by infusing some of his music with social commentary. At the 1987 Sonic Circus in Wellington, he presented a work for orchestra plus tape and video, Black and White. This was a personal perspective on the 1981 Springbok tour, which had aroused political protest and civil violence to a degree never previously experienced in New Zealand’s well-ordered backwater.

Black and White is a potent piece, an emotionally concentrated political statement. The years between the events that inspired it and its premiere had not softened any of the scar tissue; emotions still ran high. During the performance a number of NZSO players laid down their instruments and walked off the stage in protest. They objected to being the mouthpiece for a political viewpoint they didn’t necessarily support. This action could not have been scripted to better effect. A confrontation of issues that had created so much social division was met by a performance that was itself beset with tense emotions and divisive bebehavior. Some in the audience stormed out while others gave a standing ovation. Seldom is an artwork so aptly titled!

Cree Brown is not alone in using music to vent his political concerns. Douglas Lilburn’s heart-rending Poem in Time of War (1967), an electroacoustic work protesting against the excesses of the conflict in Vietnam, As Though There Were No God (2003), by Ross Harris, which moves the spotlight to Iraq, and Helen and David Bowater’s theatrical The Chafing of the Stump (1987), a meaty smorgasbord of animal carcasses demanding vegetarian relief, give a sense of the spectrum of issues that can give rise to art laced with political messages.

But politics is only one among many landscapes that Cree Brown chooses to explore. In 1999 he found himself at Scott Base participating in the Artists to Antarctica programme. An electroacoustic work, Under Erebus, that issued from this experience involved the manipulation of the unique soundscape he encountered: wind, penguin calls, crunching footsteps and a variety of other sounds, recorded both above and beneath the ice. Under Erebus is a haunting evocation of an alien wilderness rendered with exquisite timing, a million miles from the long- baton charges of the Red Squad.

Cree Brown’s 2002 installation Aeolian Harp in Christchurch Botanic Gardens—an instrument that played shimmering harmonics in the lightest of breezes—revealed yet another startling and subtle dimension to his work. Like fellow Christchurch composer John Cousins, he creates at the cutting edge of an experimental music that blurs any meaningful distinction between music, performance and other branches of the visual arts.

When douglas lilburn died on 6 June 2001, it was a significant day for New Zealand music. Nevertheless, the event rated only a small column on an inside page of those newspapers that chose to mention it—the merest media blip compared with the outpouring of public grief that accompanied the death of a prominent sportsman a few months later. Such muted acknowledgement, however, was all too accurate a gauge of the profile and popularity of contemporary music in New Zealand.

Lilburn was a towering figure, a pioneer who left behind a body of work that made New Zealand music a viable concern. He studied with Ralph Vaughan Williams at the Royal College of Music in London during the late 1930s. A founding lecturer at the music faculty of Victoria University, he established the electronic-music studio there and became a pioneer of the medium.

Having built a reputation as New Zealand’s leading composer with an eloquent individual writing style that at times evoked Vaughan Williams, Sibelius and Stravinsky, Lilburn changed tack mid-career, pursuing a new idiom for self-expression. At an open lecture at Otago University in 1969 he explained:

“I felt the impact of a revolutionary new music stemming from Darmstadt, and also of a radically new medium of electronic sound. This situation became alarming, began to make me feel that unless I somehow kept up with all the new developments I might be condemned to a musical inconsequence or sterility. Of course, in human or musical terms this would be intolerable—to spend one’s life keeping up with the Darmstadt Joneses.

“But for a time I really felt as though I’d taken a tumble through the looking glass, and I would have to run faster and faster even to keep in the same place. It turned out not to be that, but a curious thing postulated by 16th century navigators, and perhaps by Einstein—roughly, that if you travel far enough in the same direction you arrive back in the same place, but a different person.”

Lilburn’s musical curiosity and taste for experimentation influenced the next generation of artists, setting the course new music has since taken in New Zealand. He formed Waiteata Music Press, which publishes works of New Zealand composers, and in 1984 founded the Lilburn Trust, a generous and largely invisible hand that has fostered the growth of composition in New Zealand, thereby helping promote a Kiwi artistic identity. His legacy cannot be overstated.

Composition would hardly exist in New Zealand without the fostering hand of the universities. Some composers work as lecturers, and ex-students often retain lecturers as mentors who encourage their efforts in a largely indifferent marketplace. Trapped by circular dependence, composition has suffered from an ivory-tower stigma, galling for practitioners who long to see their art accepted by a wider public.

Composers insist that music is, or can be, a serious art form and need not be treated as ear-candy. They ask audiences to extend themselves when listening and to accept that the effort required to unravel a work will lead to a commensurate reward, just as it does in the literary, visual and dramatic arts. The basis of any creative work is experiment—bold experiment—and irreverence. Bach and Beethoven were revolutionaries, too, in their time. But getting that message across is an uphill battle.

In 1995, Dame Kiri Te Kanawa stirred up an anguished howl of protest with a flippant remark delivered during a TV interview in South Africa. She had been employed to sing the theme song for the Rugby World Cup, being staged at the time in that country. Asked if, while in South Africa, she would be performing any New Zealand music, she replied: “No, I’m sorry. We haven’t got a wealth of composers out there unfortunately.”

Invited to respond to this comment, composers sent an avalanche of outraged letters to Music in New Zealand, the (now sadly defunct) magazine for the musical fraternity. Of course, Dame Kiri’s principal repertoire is pren20th-century operatic, and it is perfectly true that no indigenous work from that period and genre exists. But her remark was nevertheless a strangely dismissive one for New Zealand’s leading musical icon to make.

Auckland composer John Elmsly noted in one of many open-letter responses: “Divas are narrow specialists who excel in a small number of famous roles—success partially guaranteed because the music is so familiar that beautiful mimicry is more important than the ability to fashion a great performance from the unknown.

Elmsly’s response encapsulates a defining dilemma for composers. Audiences are drawn to what is familiar, composers to its polar opposite. The unknown is a bad place to be working if you want to be popular.

[Chapter Break]

Popular music is virtually a soundtrack for our lives—in shops and cafés, piped through work places, blaring out of cars and sports stadia, or dubbed into movies, TV dramas and documentaries—and classical music and jazz nurture smaller slices of the public consciousness, but there are few outlets for contemporary art-music.

Radio New Zealand’s Concert FM sets aside broadcast time in which it features new and home-grown music, but it is the only branch of the media that shows any significant interest. Major newspapers usually review, and sometimes preview, performances in their arts sections, and some are very good, such as the New Zealand Herald, which employs William Dart. But there has always been a small number of reviewers who show little empathy, or even display a feral dislike, for contemporary music. I recall sitting next to a Wellington critic who shamelessly and loudly snored his way through a performance and still managed, in the next day’s paper, to dislike what he hadn’t heard. Artists should be critiqued according to the deficiencies of their work, not judged against the deficiencies of their reviewer. The paradoxical prerequisite to survive for any artist, it seems, is a thick skin to complement heightened sensitivity.

Until recently, New Zealand works have tended to feature only rarely in, and even to be completely absent from, the concert seasons of some orchestras and many ensembles. The situation has improved dramatically in the last few years as a number of dedicated contemporary chamber groups have sprung up in the main centres and established institutions are at last seeing the wisdom of fostering home-grown talent.

We have also witnessed the coming of age of large-scale arts events in this country such as the New Zealand International Arts Festival, the Asia Pacific Festival, and the Auckland Festival. The size and importance of the New Zealand International Arts Festival, a multi-arts event, make it a major contributor to the commissioning and performance of new music. The Asia Pacific Festival highlights composers and brings to New Zealand leading performers of indigenous instruments, allowing us a glimpse of what is happening in the region.

The NZSO now takes a very active role in commissioning, premiering, workshopping and generally fostering new music. In its 2006 concert season, it premiered five works by New Zealand composers. This is in stark contrast with seasons over the previous decade that boasted little or no home-grown content, a situation equivalent to the National Art Gallery omitting New Zealand works from all its exhibitions.

Even in these more enlightened times, the problem of too few opportunities for composers has not been completely remedied. The five premieres of commissioned works given by the NZSO plus three by the Auckland Philharmonia Orchestra, also in 2006, amount to performances of new works, by two of the country’s top orchestras, of less than 2 per cent of its composers. It is a sad fact that many, among them some highly promising original artists, will never be commissioned by—or even have the opportunity to write for an orchestra.

Proof of this can be seen in the number of entries submitted for the Douglas Lilburn Prize, a triennial competition run by the NZSO and Concert FM. Part of the prize is to tries were received. For far too many composers this contest is that all too rare a thing: the opportunity to write for orchestral forces with the prospect, however unlikely, of actually being performed. In 2000, the competition was deservedly won by Penelope Axtens with her work Part the Second, but there were many other fine entries, such as Nightdances by runner-up Michael Norris, which at the very least deserved a commission fee. Norris won the competition in 2003 with his Rays of the Sun, Shards of the Moon, so poetic justice might be said to have been meted out for him, and in 2006 Lissa Meridan scooped the prize with This Present Brightness, but numerous other artists have found themselves working on substantial pieces without pay.

The Auckland Philharmonia Orchestra has shown a commitment to Kiwi composition over many years. Aside from regularly commissioning new works—and being adventurous in its commissioning practice—it runs a resident-composer scheme. This accommodates one highly trained, uniquely skilled composer each year in a paid position with an income at the giddy level of a building labourer’s. The APO has limited resources, and composers have learned to accept low wages for their services, so this is a highly sought-after post. In 2007 Gareth Farr will be added to a list of composers who have held the APO residency, which reads like a who’s who of New Zealand composition.

Other significant residencies are the Creative NZ, NZ School of Music in Wellington and the Mozart Fellowship attached to Otago University, and from these stipends a fortunate composer might enjoy a few years of steady income. But there are few who can draw a sustained living from composition alone. Wellingtonian Farr and Dunedin’s Anthony Ritchie have generated sufficient appeal to be regularly commissioned, but even they are occasionally confounded by the vagaries of the marketplace. Most composers have to teach or lecture in music, copy scores, work at other day jobs or depend on family members to top up whatever erratic commission fees they might command.

Unlike in the visual arts, where a painter or sculptor can build up sufficient demand for their work to live on the proceeds of sales, in this world there is no tangible product for a composer to sell, apart from a one-off performance that is thereafter lost to the ether. Compact discs are costly to produce and, with performers being major stakeholders, fraught with copyright issues, while new composition commands only a tiny market share in any case, all of which makes CDs an insignificant source of income. Given these conditions, Creative New Zealand has become a major supporter and funder of composition.

Not all performers are prepared to play the music that results. For a vocalist, unconventional demands can lead to a ruined larynx and an early end to a career. Some instrumentalists also see innovation as a fast track to oblivion. Where recitals of classical music, a repertoire practised and honed since school days, might lead to packed houses and prominent solo careers, new music seems to generate incomprehension and even open hostility.

A musician who has flown in the face of conventional wisdom is pianist Dan Poynton. His first solo album (on Rattle Records), You Hit Him, He Cry Out—the title apparently comes from Papua New Guinea pidgin for “piano”: big fella, many teeth, you hit him, he cry out—won Classical Album of the Year at the 1998 New Zealand Music Awards. It contains a selection of New Zealand piano works drawn from a repertoire Poynton has toured extensively.

The success of this album was hard won. The automatic assumption made by concert promoters that audiences are interested only in the established classical repertory means Poynton is always fighting to be heard.

“You have to slog your guts out if you want to play New Zealand music in New Zealand. You’re always battling to convince people that they should be wanting to hear it especially concert promoters and bureaucrats—because usually the audience really digs the ‘indigenous’ when someone finally corners them into listening to it,” he says.

Poynton is an engaging character, more in the mould of a roving minstrel than a white-tie performer. He seeks to involve his audiences by talking freely about works or their authors so as to illuminate their mysteries, while handing out chocolate fish. He is as close as the local art-music world comes to having an ambassador.

In recent years Poynton has been recording the entire piano works of Douglas Lilburn over four volumes. Volumes one and two are completed, and incredibly—given Lilburn’s status—they contain works that were previously unrecorded. Volume one was voted Best Classical Album at the 2005 New Zealand Music Awards.

“Deep down I love the stuff my country produces, and I wouldn’t feel relevant if I was just churning out Mozart and Chopin all the time,” he says.

Other fine musicians who carry a selection of Kiwi scores in their travel bags are violinist Mark Menzies, clarinettist Andrew Uren, and Alexa Still, who is a lecturer in flute at the Sydney Conservatorium. Working as a professor at the California Institute of the Arts, Menzies has earned a reputation for his willingness to tackle challenging new work.

On his visits to New Zealand, he makes a point of performing new material from abroad; conversely, he inserts as much New Zealand music into his international performances as he can.

Among the leading chamber ensembles that actively promote new music are two based in Auckland: Karlheinz Company, founded by composers John Rimmer and John Elmsly, and 175 East, whose artistic director, James Gardner, is also a composer. Wellington-based Stroma, like 175 East, counts top performers in its ranks. All three chamber groups perform an innovative repertoire of works by living composers. The excellent NZ String Quartet tours indigenous works, as does the NZ Trio. New Zealand works can also be found in the programmes of many local and overseas choirs, particularly the award-winning Tower New Zealand Youth Choir and New Zealand Voices. With the enthusiasm of key people such as Peter Godfrey and Karen Grylls, many composers have been encouraged and inspired to contribute to a large repertoire of NZ choral works.

[Chapter Break]

New music has traditionally fared somewhat better overseas than it has in New Zealand. In Europe and the US, performers such as the Kronos Quartet or deaf Scottish percussionist Evelyn Glennie have busy performing schedules, playing nightly to packed houses. Some New Zealand composers have recognised this and followed their fortunes offshore.

John Psathas is one of the generation of mid-career composers who, like Gareth Farr, has made waves with his music. Psathas began forging an international profile when Glennie took up Matre’s Dance, a high-energy duet for piano and percussion, touring the world with it in the early 1990s. Noting the public response to this work, Glennie added more Psathas pieces to her repertoire, setting off a snowball effect. Psathas is now in a unique position among New Zealand composers. He is regularly performed by the world’s finest orchestras, ensembles and musicians. His first album, Rhythm Spike (Rattle Records), won Classical Album of the Year in 2000, and the follow-up album, Fragments, took the 2004 award.

Psathas’ View From Olympus was premiered at the Royal Gala Concert for the XVIIth Commonwealth Games in Manchester in July 2002, a prestigious event at which the composer shared concert billing with Dame Kiri Te Kanawa, and a new album of this title has just been released.

Selected from among hundreds of international contenders, Psathas was one of the official composers for the 2004 Olympic Games in Athens, as a result of which his music was heard by hundreds of millions of people around the world. He now rivals film-maker Peter Jackson for having the largest international audience of any New Zealand artist.

Early on in his career, Psathas had problems with musicians struggling to play his material and altering his score to match their own technical limitations. His music is notorious for its demanding, driving rhythms, which require great virtuosity to perform. But an unexpected benefit flows from the difficulty of his work, which is that the world’s finest musicians are often interested by the challenges it poses—it stretches them—and so they beat a path to his door. With the calibre of performances he now receives, he is able to write to the limit of technical possibility with total confidence.

Psathas now enjoys an international reputation which eclipses that of all other New Zealand composers—a feat all the more remarkable given that, like Jackson, he remains adamantly based in Wellington.

Looking further afield, a number of elite Kiwi composers have pursued performers and audiences by making their homes offshore. Among these Annea Lockwood, a leader of the 1960s New Zealand avant-garde, lives and works in the US, while Denis Smalley and John Young have gained noteworthy reputations in Europe.

Gillian Whitehead has spent most of her artistic life abroad. She studied with Sir Peter Maxwell Davies in Britain and benefited from QEII grants that allowed her to live and work in Italy and Portugal. Making a base in Australia she became firmly established, teaching at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music for 15 years, and is one of the most highly esteemed composers in Australasia.

Whitehead believes that her time in self-exile had the effect of stimulating a desire to delve more deeply into her Maori heritage. She reflects how, on her return home, “it was wonderful to find that this country had been undergoing a renaissance in things Maori!”

Collaboration with Richard Nunns, a leading light in the revival of taonga puoru—traditional Maori instruments—enabled her to explore a subtle and evocative sound world. “Richard was important in the direction my music was taking. I discovered that after working with him, a range of smaller, more subtle sounds began seeping into my writing.

Whitehead’s 1998 opera, Outrageous Fortune, dealt with the tensions between the Otakou (Otago) Maori and the 1860s gold-rush settlers. The cast included a number of rising Maori operatic stars, while Nunns played 15 taonga puoru. These ranged from instruments made of gourds, shells, pounamu and wood, to bone flutes and bull-roarers, and were set alongside a lighter than usual ensemble of conventional orchestral instruments. The opera proved very popular with Dunedin audiences. Whitehead attributes this acceptance to the work’s local setting and its weaving together of stories of ancestors both Maori and settler.

Given that she is one of New Zealand’s most experienced composers, it might be surprising to hear her speak of new challenges, of a new musical course that she aims to navigate—moving out of her comfort zone and into the formidable electronic media—but it shouldn’t be. There tends not to be much money, prestige or security in the profession. But there is a boundless enthusiasm for new ideas.

[Chapter Break]

By circular fortune I found myself back in Edinburgh a couple of years after the first trip, in time for the next New Zealand, New Music festival. A contingent of Kiwi composers was again present, along with some Kiwi musicians who had been strutting their stuff the week before at a festival in Amsterdam. A cold, miserable rain slanted in from grimy skies it was decidedly bleak this time—but there again was Greyfriars Kirk, pulsing with Pacific warmth like a tunnel opening into southern latitudes.

Creative NZ supported both festivals to a limited degree, but most resources came from British institutions: the Edinburgh Contemporary Arts Trust, the Scottish Arts Council, the British Council, to name a few. Despite their assistance, a general lack of funding plagued the organisers and finally led to an abridged programme for the second festival and the curtailing of future festivals. Kiwi sponsors should have been falling over themselves to be associated with this showcase enterprise in a major marketplace, but the arts are a hard sell, and, among them, contemporary music is a destitute cousin.

Nevertheless, at the festival I felt a sense of wonder that despite a general lack of public awareness, this music is flourishing right under our noses. We New Zealanders place huge importance on sporting results and scrutinise minutely the private lives and prognostications of people famous for just being famous—all of which will fade into oblivion in decades to come. Our cultural history, on the other hand, will endure, being forged as it is in an era that will probably stand out as an especially fertile age to our descendants.

In that open lecture in 1969, Lilburn quoted Cicero: “If you ask a farmer for whose benefit he is planting, however advanced his age, he will unhesitatingly reply: ‘For the immortal gods, who have ordained that I should receive these things from my ancestors and hand them on to my descendants.”