The shipping news

Of all the changes in the shipping industry in the past few decades, the most far-reaching has been the containerisation of cargo. Auckland, New Zealand’s largest container port, handles nearly half the country’s container trade. The reorganisation of facilities to ensure the efficient handling of more than 1500 steel boxes a day has transformed the port—here coming into view on the bridge of Contship Borealis, one of the world’s largest container ships.

The blue hull of the container ship Contship Borealis looms above me as a steel wall, giving me a sudden jolt of vertigo. Against the darkening sky I can make out tiers of containers on her upper deck. From my viewpoint idling alongside this 46,000-tonne behemoth in a Ports of Auckland pilot launch—they look like so many stacked building blocks.

In fact, the whole ship is Lego writ large, a floating confirmation of the principle that form should follow function. There is little of beauty in the vessel’s visible lines. All the elegance, I am told, lies hidden beneath the water, where equations of flow dynamics have formed pleasing sculpted curves. Above the Plimsoll line, utility rules. And here, as elsewhere in the world of commerce, utility expresses itself in efficiencies of scale.

Everything about Borealis is big. She is the length of three football fields, and in her holds and on deck she can carry the equivalent of 4100 20-foot (6-metre) containers stacked 14 tiers high. Yet, if asked to, she can crank along at 25 knots—that’s a sharpish 46 km/h. Someone with time to spare has worked out that all those steel boxes laid end to end would stretch for 25 km. Stacked one on top of another—in this Everest year a more fitting calculation—they would rise to three times the height of Mt Cook.

Borealis and nine other “4100s” being introduced to the New Zealand run by CP Ships and by P&O Nedlloyd are also the world’s biggest refrigerated container ships. Each one can plug in 1300 refrigerated containers—“reefers” to those who work them. P&O Nedlloyd’s fleet alone has a chill capacity greater than all the domestic refrigerators in New Zealand combined.

And there is the nub of the thing. In the 1880s, the country’s trade was revolutionised by shipboard refrigeration, which allowed frozen carcasses of mutton to be sold half a world away. Today, cargoes as varied as beef, fish, vegetables, ice cream and tulip bulbs are exported chilled or frozen. The new reefers, each with its own built-in refrigeration plant that can be kept running while ashore or in transit, are a generation removed from the old system of stacking goods in insulated containers, with portholes and sliding flaps, chilled by a ship’s external refrigeration system.

[Chapter Break]

The speed and carrying capacity of the new fleet, along with its ability, for the first time, to offer scheduled weekly sailings to the east coast of the United States and to Europe, are good news for New Zealand companies fighting to gain an advantage amid the cut and thrust of global trade.

New Zealand sits at one end of the world’s longest trade route—21,000 km from Europe—and despite the romance that still clings to ocean voyaging as stubbornly as seaweed round a keel, sea-borne trade is predicated on hard-nosed bargaining. Which is why Ports of Auckland managers danced a jig or two when, late in 2002, it was announced that Auckland, along with Napier and Port Chalmers, had won the tender to become a fixed port of call on the so-called eastabout service for the big 4100s. It also became the only port of call for the smaller 2200 TEU (“twenty-foot equivalent unit”) container ships circling the globe westward.

A lot went into preparing the ground for that bid: new high-speed cranes, more powerful tugs, a snappy information system, even the creation of what are termed “inland ports” near Auckland’s factories in order to process and shift goods more efficiently.

It is with a sense of occasion, then, in the lee of that great blue wall, that I clip my safety line onto the rail of the pilot launch and make for the bows. Pilot John Barker is already climbing towards a huddle of crewmen at the access hatch, which for such an enormous ship is disappointingly close to the water. Earlier, I watched another pilot negotiate the snaking ladder of a freighter for what seemed an age before making shipfall somewhere near the deck.

A few steps and I am alongside Barker aboard Borealis. We are led at a brisk clip along a brightly painted corridor that recedes into the distance. As we sweep past pipes and tubes and all manner of maritime paraphernalia, across watertight bulkheads and up a narrow companionway into a lift, I am taken with how clean every surface seems, how neat and shipshape every space. Then I realise why: Borealis left the builder’s yard in Korea just four months ago and is not far into her first 70-day round-the-world voyage.

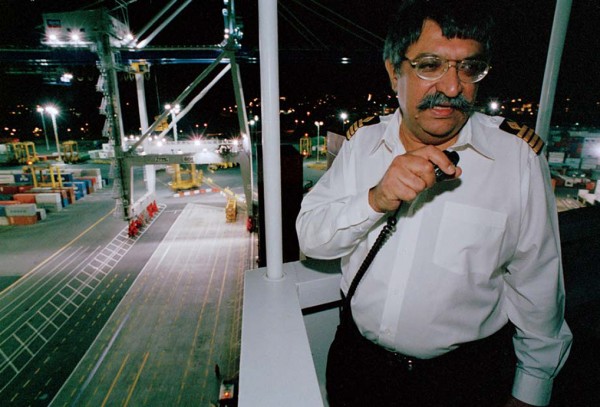

Bathed in subdued light, the genial captain, Dipak Mohan, welcomes us onto the bridge, his personal PlayStation. Electronic charts, radar screens and GPS display glow discreetly. My eyes take in speed log and engine rpm readout, rate of turn and wind direction indicators. Through the windows the Auckland harbourside winks coquettishly. There is a fine view out along the tops of the containers to the distant bow and down eight storeys to the main deck.

“The first thing to tell you, sir,” says Barker in a collegial tone, “is that the ship at the berth is half an hour late, so go dead slow ahead.”

A buoy drifts by to port. We retire to the chart room. “You’ll be at the top of the tide,” Barker tells the captain. “You will have one tug on the port quarter and one on the port bow.”

Skippers of the 4100s become particularly attentive in this harbour when talk turns to the depth of water under the keel. With draughts of more than 12 m, the 4100s have a narrow tide window in which to work the relatively shallow Rangitoto Channel. Even after the proposed deepening of the seaway in 2004, it will still be a tight fit at spring low tides. At such times, I am told, there will be barely enough of a gap between the sea-bed and the massive hull of the Borealis to fit a kitchen table.

Captain Mohan talks me through the bridge controls. At the click of a switch he can read off where the ship has come from, the distance it has travelled, its speed and its plotted course. From New Zealand it would be possible, merely by punching in destination coordinates, to have the ship self-steer to its next port of call in the USA.

In the dimness, Barker orders, “Port steer 135.” “One-three-five,” echoes the quartermaster.

The first tug joins us, making fast on the port quarter. It is 9 P.M.

I am surprised to learn that crewing on the major shipping lines is seen to by employment agencies. Most ships’ officers are, like Mohan, Indians. Europeans, it seems, are increasingly unenthusiastic about putting to sea for months on end.

“It is a demanding life,” agrees Mohan. “Hard on families.” When he first went to sea, in 1966, he was following a family tradition, he tells me. His father, uncle, brothers, cousin, nephew and son are now all aboard ships. However, such Indian maritime dominance is unlikely to survive mounting competition from China, the Philippines and Eastern Europe.

Having rounded North Head, we follow First Officer Madhn Thottankara out onto the portside bridge wing, where he undoes the top of a compass binnacle. The captain swings back what looks like the cover of an elaborate gas barbecue to reveal a duplicate set of bridge electronics. We are some 33 m off the water. Down below, in the inky darkness, the second tug, with lighted mast, spins around in the foaming sea with the energy of some weirdly magnified pond life.

On one of the ship’s lower decks a woman in a sarong makes an appearance, a young boy at her arm. They are the wife and son of the second engineer. The Borealis can accommodate five passengers, and in the interests of domestic unity, relations often come voyaging.

P&O Nedlloyd Canterbury is just vacating her berth, and Mohan gives the order for bow thrusters at full port.

Thrusters are additional propellers mounted fore and aft in small transverse tunnels in the hull. When they spin, they give sideways thrust. Theoretically, thrusters obviate the need for tugs altogether, but, since they are driven from a ship’s distant engine room by linkages, they tend to become less reliable with age. They are also prone to blockages and are less effective with light loads, when the hull rides higher.

Ashore, under the glare of powerful lights, rows of offloaded cars at a nearby wharf resemble bubble wrap. What I suppose to be a trolley turns out to be a truck. It takes a moment to make out people down there, grappling with hawsers.

Finally, and seemingly without effort, we slip in astern of the black-hulled container ship Aotea and the tugs leave us. A shore crew sees to the dozen or more mooring lines. It is just before 11 P.M. Unloading will soon begin, but Captain Mohan is unlikely to put his foot ashore during his brief stay in Auckland.

[Chapter Break]

It’s a busy old port. A week ago I stepped aboard a chartered ferry that offers a free weekly 50-minute tour of the wharves, courtesy of Ports of Auckland. On that mid-morning sailing, I joined upward of 100 others, including English-language students and two animated primary-school classes. Leaving the historic Ferry Building, we ran east to the container terminals—at Fergusson and Bledisloe Wharves—which are separated by a couple of general-purpose quays that handle break-bulk (that is, non-containerised) cargoes such as cars, timber, gypsum, wheat and steel.

We drifted past the white-hulled cable ship Pacific Guardian, there from Fiji to sit out the hurricane season. Nearby was the Wellington-registered tanker Taiko, in for engine repairs, and the slab-sided car carriers Turandot and Rigoletto. It struck me, looking at these two, that it would have been more fitting to give such affronts to aesthetics random numbers than to name them after operas.

At this point, tour guide Jan Power gave us a few figures to juggle. Auckland hosts almost 2000 ship calls and processes some 13 million tonnes of cargo each year. Fergusson, the country’s largest container terminal, and Bledisloe, it’s third largest, between them handle almost half of the country’s container trade—some 600,000 TEUs. Auckland is the main gateway for imported cars, with more than 180,000 landed here over the past 12 months, and has links to 207 other ports in 70 countries. Annual trade through the port totals some $20 billion, and the place operates 24/7, regardless of the weather—though fog has been known to bring the cranes to a standstill.

The port is a land-hungry creature, occupying a strip more than 4 km long, from Mechanics Bay, where flying boats once moored, to the Westhaven marina, alongside the Auckland Harbour Bridge. In between are cement wharves, a tank farm for bulk chemicals, palm oil and fuel, ferry piers and, on Princes Wharf, an overseas passenger terminal.

As a boy, I regularly stood on the roof-top car park on Princes Wharf and held streamers for departing friends as they were borne off on the exotic passage to Britain by the Russian liner Shota Rustaveli or by Canberra, then the biggest ship in the P&O fleet. Canberra, almost identical in size and displacement to Contship Borealis, also had to work the tide.

Princes Wharf has since had a spectacular face-lift, and the terminal now shares space with apartments and a purpose-built hotel. With air travel elbowing shipping lines out of the long-haul passenger market, business these days comes in the form of cruise ships. This season, they delivered a record 55,000 passengers to the city, pumping an estimated $105 million into the regional economy.

West of the terminal is the National Maritime Museum and Viaduct Harbour—the internationally recognised face of the city and until recently the home of America’s Cup racing.

Ports of Auckland owns almost all of this lengthy ribbon of prime real estate at the foot of the central business district, but over recent years it has been sliding east, selling or leasing out land and buildings to the west and reclaiming land at Mechanics Bay for container handling. The area surrounding Viaduct Harbour has been rendered almost unrecognisable by 600 million dollars’ worth of modish apartments, restaurants and office blocks. Now it is the turn of the nearby western reclamation, with its pipes and storage tanks and heavy-duty industrial ambience. The 14 ha site is getting the hard stare from the Auckland Waterfront Group, an organisation which is coordinating plans for its redevelopment.

Meanwhile, in a move that symbolises its changing centre of gravity, the port company shifted its head office several kilometres east, from an ugly Bean Rock Lighthouse-inspired edifice to the old Tasman Empire Airways Ltd (TEAL) building in the heart of containerville, where echoes of the flying-boat era linger in a concrete sea ramp and in Solent and Sunderland Streets.

[Chapter Break]

The morning after Contship Borealis docks, I am back at Fergusson Wharf to get a sense of how the ship’s vast tonnage of cargo is shifted. The days of hemp nets and five-ton steam cranes are long gone, as are the early-morning lines of men—“seagulls”—fronting up outside the Waterfront Industry Commission’s labour exchange on the chance of a day’s work.

I recall a pen drawing from the mid-1970s which charts the change. It showed Jellicoe Wharf on a Sunday, and the caption read: “It is a convention at weekends to line up the cranes neatly.”

Speed is the only currency these days. For both ports and shipowners it wins customers and generates profits. All investment, all reorganisation, all innovation, is geared towards doing more with less and doing it faster. At Auckland that means handling twice the cargo with half the staff. The former Auckland Harbour Board had some 1100 people on its payroll, but since Ports of Auckland took over the board’s assets in 1988, it has reduced that figure to 540.

One of the reasons for the turn-around can be seen from well beyond the port perimeter, in the shape of the massive container cranes rearing up from behind the fence like apparitions from Jurassic Park.

Each capable of lifting 60 tonnes, the Chinese-built ZPMC cranes, installed in 2002, are described as “post-panamax” for their ability to service ships wider than those that sail through the Panama Canal. Contship Borealis and the other 4100s, narrow for their length, negotiate the canal with the finest of margins, but beamier vessels are likely to come our way in the future.

My sights are set on reaching the stevedoring summit of a ZPMC. Wayne Griffin, a wharfie for more than 30 years, is the man to get me up there. He hands me a hard hat and high-visibility vest and soon we are clambering up the sort of structure familiar to oil riggers and bridge painters the world over.

“I drive these things, so height doesn’t mean anything,” says Griffin over his shoulder as we head out along an aluminium catwalk. A ZPMC can lift two containers of unequal weight simultaneously. One can be full, one empty—it makes no difference. The smaller Noell cranes alongside are out of their comfort zone with anything above a two-tonne weight differential.

When Griffin started out, all stevedoring was done with ships’ derricks and shore cranes. Some smaller container ships still carry luffing cranes, which work by lifting and swinging. Gantries such as the ZPMCs are different. They work by wheeling out a lifting mechanism between their horizontal arms, which is then lowered on cables and clamped onto a container at the corners. The container is then raised clear, the lifting mechanism rolled back in, and the container lowered to the wharf, where it is picked up by a straddle carrier—a transporter on wheeled stilts—and bundled away to storage. To work the different sections of a ship—Borealis has 65—the entire gantry moves sideways on rails.

Looking out from the cabin, I have a sense of seeing a landscape through the wrong end of a telescope. The terminal, the city and the harbour stretch away as if viewed from a hot air balloon. Meanwhile, beneath our feet cargo shifting goes on with barely a pause. The target for each crane is 30 “moves” an hour. That is, the lifting and resiting of one 20-or 40-foot container every two minutes, hour in, hour out, until the job is done.

The stevedores have already clocked up more than 1200 moves. One involved a luxury 15 m launch, which came from Brisbane as deck cargo and was floated earlier this morning.

Watching the straddle carriers glide about the terminal, I suddenly develop a hankering to ride one. Griffin obliges, and we climb back down the gantry ladder. At ground level, the straddles are bigger than I thought. Three storeys high—surrounded by gigantism I have taken to measuring just about everything against buildings—and weighing 60 tonnes apiece, they have an appealing way of getting about. Perhaps the attraction has something to do with the duplicated engines and transmissions, the ungainly stilt legs and the fact that all eight tractor-sized wheels are steerable.

I make for the bright-yellow bulk of straddle 61 and climb steadily—eight toe-hold slots in the bodywork, then another 26 steps up a ladder—to the glass cage that passes for a cab. Handler John Isbey sees me aboard. Isbey is an old hand, with four years at Fergusson under his belt and, before that, 19 at Bledisloe. His cab, which is side-on to the direction of travel, has the feel of a tree hut—an effect accentuated by my having to crouch in a corner and hold on while we’re in motion.

Straddles are run with the efficiency of worker bees. With ships on tight schedules, the days of wharfies sloping off to a quiet corner to unfold the newspaper are long gone.

“I push this button to make myself available,” says Isbey, reaching for a console above the steering wheel. Straight off, an instruction is there: Drive to CR_G (19). Isbey translates: Ship bay 19, crane G.

Stilt-walking—or, rather, stilt-rolling—around stacks of containers, we make our way to the wharf and manoeuvre over the container to be moved. Isbey punches in its number as he lowers the lifter. A green light in the cab shows we are locked on. The console gives us a position on the storage grid and we cart the container off.

This we do five or six times, and each time Isbey punches in, the console instantly flashes up another job. It never once gets rattled or asks Isbey to sit on his hands for a minute while it thinks things through.

On a busy shift, Isbey tells me, there may be 20 or more straddles in operation. Even on this low-density day, getting about has me focused on the possibility of a collision. At any minute I expect disaster to strike three storeys below as a corner of the straddle clips a container, setting the whole contraption into a slow-motion kneel.

Evidently, such a possibility did occur to the designers. A read-out indicates stability. I note that this slips to 76 per cent as we gently round a corner. Go too fast, Isbey tells me, and the console will start beeping. Quite what a driver is to do should things worsen is unclear. Find another straddle to lean against, perhaps.

[Chapter Break]

Having spent hours watching machinery being ordered about in a finely choreographed mechanical ballet, I am curious to trace the origin of all the instructions. Isbey tells me that the data stream bounces off a repeater on Mt Victoria, across the harbour, above Devonport—which, on reflection, strikes me as highly appropriate. Auckland’s first flagstaff for signalling ship arrivals was erected on Mt Victoria in 1842, when Devonport was in fact known as Flagstaff, and now, more than 160 years on, the hill still plays a part in the shipping business.

It is a short walk to the office of English-born Vic Dundas, manager of the Fergusson container terminal. Dundas, who oversees 160 full-and part-time staff, has the big picture. Fergusson handles 60 per cent of the containers that pass through Auckland. He finds the paperwork from the morning’s berthage meeting.

“Next month we will have a normal pattern for the first time this year,” he says confidently, reaching for a chair in order to talk me through the work graphs. One vessel, which had “trouble” across the Tasman, will arrive at 1700 hours today. In the schedule, it is down for three days ago. Another one, due to berth at 2000 hours, should have arrived yesterday. “And this one, down now for noon on Saturday, should have been here on Thursday night.” Another vessel is waiting at the wharf for cargo off a feeder ship overdue from the Islands.

Yesterday was quietish. One ship unloaded 106 containers; another discharged 316 and loaded 200. Rail brought in 83 and hauled out 69. Some 560 trucks showed up. And then there were a few interwharf exchanges. All up, some 2327 straddle moves.

For the sake of efficiency, Dundas tries to keep moves per container to an average of 2.4 between arrival at the port and onward despatch. Unhappily, it is one of the iron laws of logistics that efficiency goes down just when you need it to spike.

“The fuller [the wharf] gets, the more I have to move things,” says Dundas. Burying boxes underneath other boxes, in other words, then having to unearth them again.

That logistical challenge is unlikely to become any easier. Global container activity is escalating, and as shipping costs come down and technology improves, the range of goods being transported in steel boxes is expanding.

“Economies of scale—that’s what is driving the shipping trade,” says Sandy Gibson, general manager of Axis Intermodal, the company which runs Ports of Auckland’s container business.

The traditional way of charging for transportation was on the basis of commodity value, he says, the philosophy being that high-value goods such as chilled beef could stand a higher rate than, say, coal. Now the break-even point is dropping, with unexpected results.

“I saw six containers of refrigerated bread bound for Tahiti the other day,” says Gibson. “Who would have thought we’d be sending bread to the Pacific Islands?”

Or stuffing containers full of packaged timber.

This is the future, as he sees it: more containerisation, with bigger ships calling at fewer ports; ports becoming involved in managing the entire supply chain, from place of origin to final destination; and a massively increased role for technology.

This last trend is evident not just in the infiltration of offices and drivers’ cabs by data screens, but by the new tasks technology is tackling. Late in 2002, for instance, Ports of Auckland introduced an electronic monitoring system for modem-equipped refrigerated containers. The system checks conditions inside the reefers and every few minutes relays the information to the system controller. It can also diagnose faults and let technicians know what is wrong. This is all about protecting what is known in the trade as “the cold-chain integrity” of products such as chilled meat. Such detailed minuteby-minute knowledge of product conditions helps New Zealand’s Ministry of Agriculture and Forests verify compliance with OMAR (Overseas Market Access Requirements) regulations.

It is technically possible for all the information gathered to be relayed to customers via the port’s website. In years to come, fingers on the other side of the world, in Amsterdam or Paris, will pull the electronic strings, adjusting temperature settings on refrigerated containers down at Mechanics Bay.

[Chapter Break]

It is a bright, clear afternoon when I meet up with Ben Evans on Admiralty Steps, near the Ferry Building. Evans is a supervisor with Marine Services, the port arm that looks after ships from outside A buoy, at the entrance to Rangitoto Channel, to wharf tie-up.

Our rendezvous point is part of the historic wharf quarter, separated from city bustle by a newly restored wrought-iron railing. The first section of the fence, topped by ornamental lamps, was started in 1912 to enclose Queen’s Wharf, then the town’s trading hub. It was still being put up in 1913 when a general strike broke out, prompting dozens of volunteers, including farmers on horseback (nicknamed Massey’s Cossacks), to stand in front of it to guard the wharves.

The steps were once the landing stage for a half-hourly launch service that ferried officers and ratings often in full regalia—to and from the naval base at Devonport. Now the customs launch Hawk moors nearby.

While we wait to board the tug Waipapa, Evans mulls over the changes he has seen in 32 years with the port and, before that, four years on meat ships to Britain. The method for testing cold-chain integrity back then came down to seizing a frozen carcass and attempting to pull the legs apart. The meat ships lingered in New Zealand waters for a month or more while they loaded. Such dilatory practice now is unheard of and port calls have been honed to mere hours.

While we await the okay for our own departure, Evans takes me over a pensioned-off old workhorse, the tug Daldy. Once the last word in tug design, Daldy has only half the pulling power of Waipapa. Below decks, we cross a catwalk over a surprisingly large engine room—half the size of an old villa, with headroom to match. Aft, a sign outside the second mess reads “Certified for crew,” and over the entrance to the sleeping accommodation, equipped with neat bunk beds, another declares “Certified for four seamen.” Forward is a better-appointed mess and officers’ quarters. Daldy is a floating exercise in social stratification modelled on the British merchant marine.

“That’s what life was like 20 years ago,” says Evans.

Moreover, the tug is generous in its facilities. Evans’ description of it as a hotel with a ship built around it is not too wide of the mark.

Then I come across a sheet of paper taped to the wall, a relic from the days when the Auckland Harbour Board was torn down to its very administrative foundations and a new port company built from the rubble. It is a quote from the writer Petronius, dated A.D. 66. “We trained hard, but it seemed that every time we were beginning to form up into teams we would be reorganised. I was to learn in later life that we tend to meet any new situation by reorganisation, and a wonderful method it can be for creating the illusion of progress while producing confusion, inefficiency and demoralisation.”

“Those were mad, heady days,” admits Evans, and we leave it at that.

Waipapa, when we get aboard, couldn’t be more different from the old steamer. Named after the stream that once flowed into Mechanics Bay, she is a radical rethink of what tugs are all about. For one thing, accommodation is basic, verging on the provisional. Although much the same size as Daldy, she is not intended to be ocean-going. Instead of the almost universal four-strong crews—Aucklander, of the 1960s, had nine crew plus master—Waipapa is the first tug in the southern hemisphere to be designed for a crew of just two.

One of three sister ships built in Northland for Ports of Auckland—a fourth is bound for Tauranga—Waipapa’s design is based on the tugs used to shift log rafts in British Columbia. Her two 2200 hp engines power pivoting drive units which generate a combined 50-tonne bollard pull and can independently produce thrust in any direction.

As we push out through the Waitemata chop towards the big black hull of P&O Nedlloyd Botany, I notice another innovation: the cabin is raised clear of the deck. This reduces floor vibration and, cunningly, allows the bow winch to be used for stern towing, with a line running aft under the cabin, thus dispensing with the need for a second winch.

As skipper Graham Browne gently brings 383 tonnes of tug to bear on the steel wall of Botany, the mast above the tug’s wheelhouse cranks back hydraulically to avoid hitting the flair of the visitor’s looming hull.

The VHF transceiver comes alive: “Full power push for’ard.” It is the voice of another local pilot on the distant bridge.

“I love bulbous bows. They are a marvellous invention,” Evans declares as we churn water near Botany’s partly submerged battering ram. Two or three metres long and broad enough to sit on, its rounded back is, surprisingly, dry. “The theory is that the bulb moves the bow wave further aft to the point of least resistance.”

“Full stop for’ard.”

Botany’s anchor, all 12,500 kg of it, hangs no more than 10 m above us.

“Something to be mindful of if things go wrong,” says Browne, following my glance. Standing squarely at the controls, a joystick in each outstretched hand—one for each spinning prop—he has begun “walking” Waipapa sideways in company with the ship. The tug isa sheepdog on castors, and close enough to magic to fill the dreams of an Ahab.

I think back to the heavy old Aucklander, with its steam engines coddled by three engineers and all commands rung down by telegraph.

Meanwhile, Evans is running his eyes over Botany as she inches towards her berth. He confesses to having taken endless snaps of visiting ships during his time on the tugs. He has albums full of photos. “My wife took the camera off me in the end,” he says.

Ports are like that. They are the well-stocked fairgrounds of commerce, with everything in noisy motion—entrancing, inviting, casting a spell. Thinking back over my recent experiences—clambering up ships’ ladders, sitting with crane operators, flitting about in straddles—I admit the spell has worked just fine on me.

[Chapter Break]

The last journey I make is notional, aboard a container ship that carries no cargo and has no manifests. No crew labours on her deck, and there is no fuel in her tanks. At a word, a tug materialises off the starboard bow and keeps pace. Swell builds up. Fog rolls in from the direction of Bean Rock. Then, as if on a whim, night falls and the stars shine through. Up-channel beacons begin to pulse out their guiding lights.

This voyage toward Fergusson container wharf began just a few kilometres away in Devonport, in the Royal New Zealand Navy’s Bridge Simulator Facility. Showing me the ropes is naval frigate commander turned civilian Greg Buchan, whose baby this is.

The simulator is an electronic marvel. It replicates the controls and sounds of a real bridge, down to the 240-degree view through the bridge windows, courtesy of nine projectors, a curved screen and a Norwegian computer program. It even models the increased draught of a turning vessel and the pressure effect when one vessel passes another.

Adapted by Buchan and his assistant, chief petty officer Brett “Spanner” O’Toole, to mirror Auckland conditions, the program allows a person to take the helm of a range of vessels from the navy diving tender to an 80,000-tonne container ship and attempt to get it safely into harbour.

Quick to spot a good thing, Ports of Auckland contracted the navy to model the proposed deepening of the commercial shipping lane to see how the big 4100 container ships will fare and to check locations for navigation lights. The navy’s conclusions: the dredged channel will work just fine, and if a skipper grounds a tanker in full view of commuter traffic, it will be no fault of the beacons.

Buchan advances the program to daylight.

“Spanner, can you give us the Oriana steaming out of Auckland?” he asks. Behind glass to our rear, the chief petty officer taps his keyboard and in a trice there is Oriana, rounding North Head.

“Keep an eye on her bow,” Buchan tells me as the liner steams toward us in a graceful arc. For a while I see nothing; then, in the creaming water at her stem, I sight the playful leap of dolphins. Spanner’s work, evidently.

“Really, you are only limited by your imagination with this,” says Buchan. He points through the bridge windows to the attractive green fields that seem to cover most of Auckland. “This isn’t a very mature visual. As we find time, we’ll put in the houses and important buildings like the museum and the hospital.”

And the Fergusson terminal land reclamation, no doubt. That, after all, is where the million or more cubic metres from the bed of Rangitoto Channel is destined for once dredging begins in 2004. The 18-month exercise will create a welcome 10 ha extension to the crowded terminal and add a new berth, while avoiding the need to dump material at sea or use the city’s scarce quarry rock.

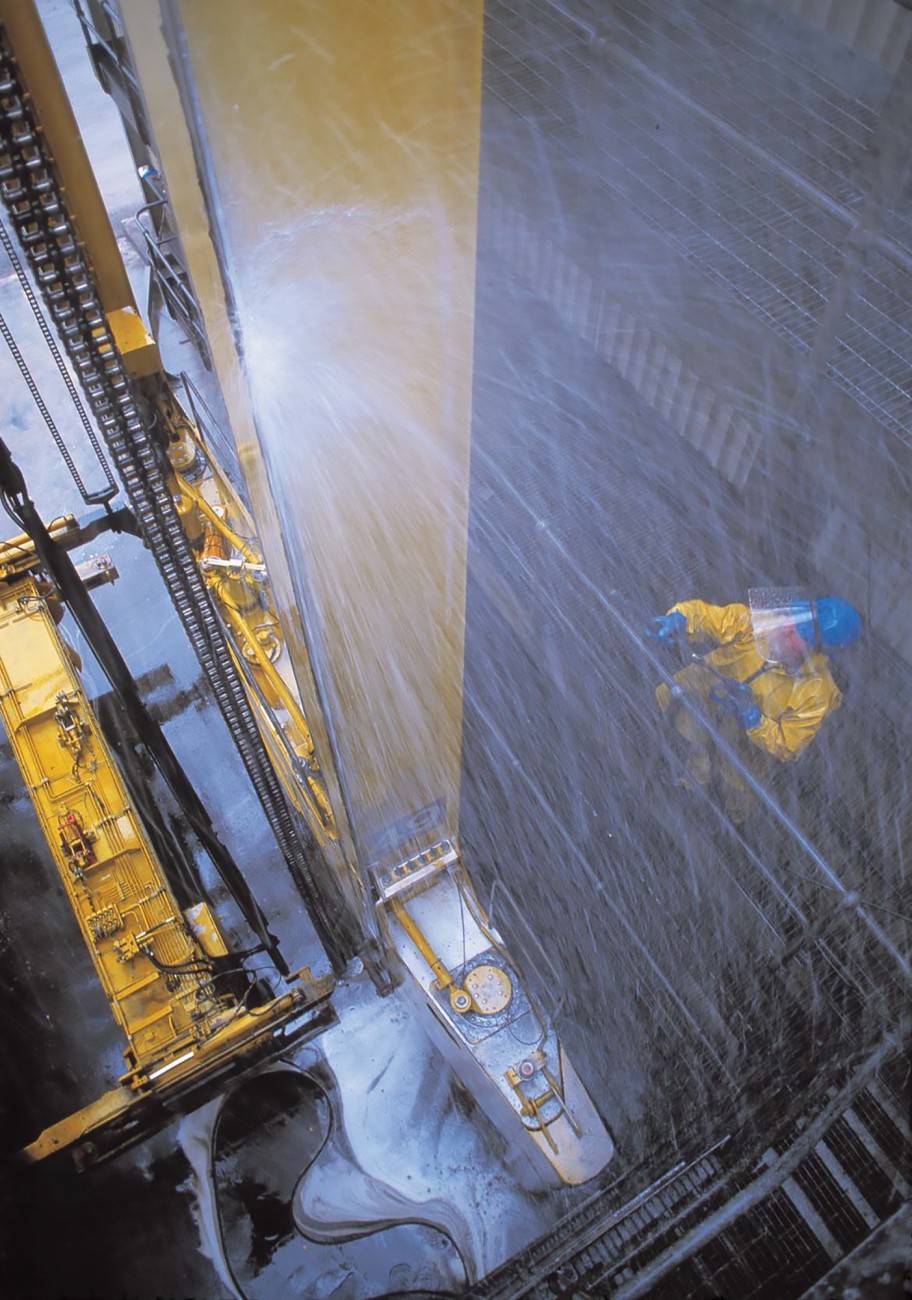

The reclamation is already receiving some 25,000 cubic metres a year of maintenance dredgings that were formerly loaded on barges and towed out beyond Great Barrier Island to be dumped. A novel approach is used to stabilise the mud: adding cement. The finished product, “mudcrete,” can be walked on the next day, has the look of natural sandstone and can be built on.

Mudcrete is the province of civil engineer Murray Dennis, who directs the operation from a no-frills Portacom office 30 m back from the sea wall. When we meet, Dennis plays me a short video showing a cobbled-together machine—the mudcreter—at work. The machine itself is away getting its annual certification, but the video tells me what I need to know. Two hoppers feed the raw materials—cement and sea-bed ooze—into an oversized mixing trough with rotating paddles, and a conveyor belt then carries the slurry out to a waiting barge to be deposited where needed. Expense was spared in the making of this contraption. Dennis picked up the mixer, and a back-up spare, second-hand from a fertiliser works in Bangkok. The power plant consists of two old straddle motors.

We walk out onto the newly won land, which in texture and colour resembles the cliff faces that ring the harbour’s beaches. The reclamation was given the green light only after some searching questions had been answered. Chief among them: would putting the entire container operation elsewhere be a better solution than tweaking Fergusson?

Planners had entertained such thoughts half a century earlier. In 1949, Parliament handed over to the Auckland Harbour Board 2800 ha of tidal land in the upper Waitemata, and the board bought a further 160 ha of land at Te Atatu with the idea of developing a port and bulk-storage area. Nothing came of this, and it was only with the need for more container space that eyes were once again lifted to the horizon.

A 1999 report looked at six proposals, ranging from floating ports at Muriwai, on the west coast, and in the Waitemata to land-based ports on Ponui Island and at Karepiro Bay, at the base of Whangaparaoa Peninsula. The report concluded that in terms of cost, environmental impact and almost every other consideration, nothing stacked up as well as the planned portside reclamation.

Tipping rock and mud into the tide has been the way of things in Auckland since the town was founded in 1840. Over the 160 years since, more than 40 separate projects have added 160 ha to the foreshore—a trend anticipated in Felton Mathew’s original survey plan of 1841, which, through the expedient of dotted lines, reclaimed both Commercial Bay and Freemans Bay as future building sites.

The problem then, as now, was ships’ draughts. In the 1860s, tidal mudflats rendered the port better suited to the Maori canoes laden with produce that were hauled out on the waterfront than to ocean-going vessels. Hence the prodigiously long Queen Street wharf of later years. Visiting Royal Navy ships sensibly chose to anchor in the relatively deep water off Devonport, where the Royal New Zealand Navy later based itself, leaving Auckland’s elders to overcome the problem of shallow water closer to the city.

This they did, if gradually. Now the entire downtown area, as well as much else—including Victoria Park—sits below what was once the high-tide mark. With no strong currents and no large river discharging nearby, maintenance dredging over the years has been a straightforward affair. Nor should the present reclamation prove difficult. With a few swipes of the mechanical bucket, the water east of Freyberg Wharf, immediately alongside Fergusson, has been deepened to 13 m, and, behind a new bund, tonnes of mudcrete are being fashioned into a surface.

“As the first hectare is done, we’ll give it to the terminal and I’ll move the Portacom further out,” says Dennis. His pleasure at the prospect is readily apparent.

We look out to sea, where bright sun glints off the restless waves. Pleasure craft and work-boats ply the water. The rotors of a distant helicopter beat air as it makes for the pad at Mechanics Bay. A sea scent permeates everything. I have to agree it is a fine place for an office.

Behind us, on Fergusson Wharf, the straddles bustle about in the heat of the day like giant ants with eggs as the gantries wind yet more containers from the holds of a 4100. They are indefatigable, these machines, devices geared to shifting the steel boxes that are the life-blood of the country’s economy. Boxes that are the unflattering, indestructible gift-wrap of our 21st-century cargo cult.

And, one way or another, as I have discovered, they are the cause of just about everything that happens down here at the wharves.