The people’s bird

How did the kiwi become a star?

Among the panoply of lions, wallabies, bears and eagles that represent their countries, the unprepossessing kiwi stands (as opposed to flies) above the rest, for no other creature has given its name to both a nation’s inhabitants and its culture. The fact that this remarkable feat is probably the result of an Australian initiative only makes the symbolic rise of the kiwi more ironic, given trans-Tasman rivalries.

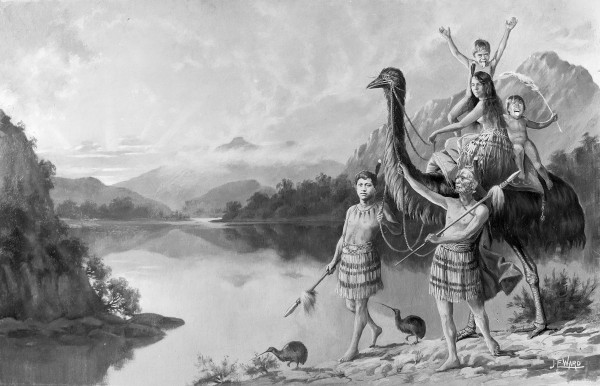

A more unlikely candidate for national stardom cannot easily be imagined. If the camel was concocted by a committee, responsibility for the kiwi must surely have fallen to a minor subcommittee. A walking stick for a beak, whiskers of a cat, legs of a kickboxer, wings of a hummingbird, an ostrich’s egg and a hedgehog’s snuffle—little wonder 19th-century ornithologists regarded it with incredulity. For all its eccentricities, the kiwi was well adapted to its natural environment.

One of the first and most enduring international platforms for the national bird, rose to prominence on the parade grounds of the British Army. The kiwi’s lack of limbs suitable for carrying weapons proved no impediment to the nation’s cartoonists, who found the conflict with Turkey during World War I a fertile source of puns.

For tens of millions of years, it quietly got on with the business of keeping the insect and worm population under control. The arrival of humans on the scene, however, presented some major changes. One of these was the threat of extinction, which the kiwi ignored for the time being. The other was the prospect of gainful employment. As it happened, the kiwi proved the right bird for the job.

Within a few years of settlement, colonial New Zealand went in search of an identity. Part of the natural process of growing up, this need for self-definition was particularly urgent in a country conscious of its youth and isolation. New Zealand needed symbols, and could draw on two rich sources: the old world and the new environment.

The first category included a range of lions, crowns and royal regalia, and offered a sense of tradition and history that the young colony so obviously lacked. Alongside these imports were home-grown alternatives which exploited the country’s natural features and the culture of its indigenous people.

The ubiquitous bush, now threatened by axe and match, was such a source. But if New Zealanders were hoping for an antipodean equivalent of the British lion or American eagle, they were to be disappointed. Denied any noteworthy mammals by the untimely break-up of Gondwana, the local field of exploitable animals consisted largely of birds. Kiwi, kea, kaka, tui, moa and huia all became popular images in due course, but the last two were eventually disqualified on the grounds of extinction. Although the huia had only recently departed, the moa came to be regarded as too much of an archaic oddity to qualify for iconhood.

Had it been speed and colour New Zealanders were after, the kea and kaka would have fitted the bill. Had we opted for elegance, there was the tui, with its melodious call and chic plumage. That the kiwi prevailed suggests that rugged individuality was the virtue we cared most about, and certainly one essential to any emigrant contemplating a life in the colony.

[chapter-break]

The kiwi is an aggressive bird when provoked, and its career prospects as a symbol were advanced by the imminence of war. In the early 1900s, this country could barely wait to get embroiled in battles abroad, all in the cause of Empire.

Desperate to demonstrate physical prowess and allegiance to Mother England, we dashed off to South Africa, and later to Europe and the Middle East. We went variously as Fernlanders, Maorilanders and En Zedders, and the grim experiences of 1915 added Diggers and Anzacs to the list.

Strangely, we have a small commercial product to thank for clarifying and consolidating the naming situation.

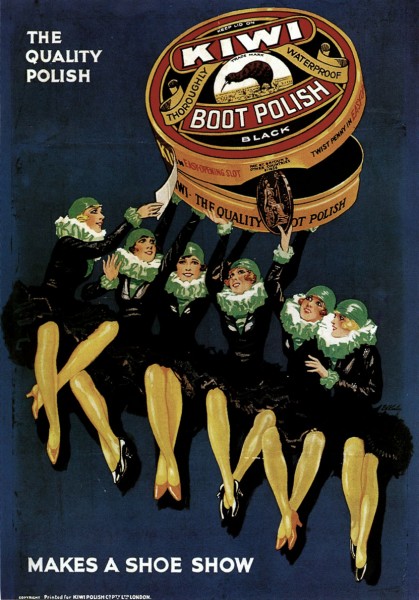

In 1910, Miss Annie Meek from Oamaru married an Australian, William Ramsay. The couple went to live in Melbourne, where Ramsay had developed a new boot polish. In need of a short, easily pronounceable and memorable name, and a symbol that lent itself to application on a small, round tin, he hit upon an image from his wife’s homeland. Kiwi polish was born, and Ramsay sold 100 tins on a sales trip to Sydney.

Things really took off in 1917, when the Kiwi Polish Company was favoured with a massive order from the British Army. By war’s end, it seems that wherever New Zealand soldiers went they were preceded by a tin bearing the distinctive name and image of their unique bird. Before long, Fernlanders, Maorilanders and others became known as Kiwis.

Understandably, the idea that it took an Australian to develop our national identity has proved unpalatable to some. There have been suggestions that the true origins of Kiwi polish lie in a shed near Martinborough, deep in the Wairarapa.

Like the polish, the concept of the New Zealander as Kiwi spread quickly, aided by several factors. During World War I the Kiwi Concert Party spread the word to the troops in Europe, and the biggest kiwi image of all was carved into a chalk hill on the Salisbury Plains for the benefit of New Zealand servicemen based nearby.

Back home, Trevor Lloyd started using the kiwi as his symbol for New Zealand and its troops in cartoons for the New Zealand Herald and the Weekly News. His renditions of bellicose birds skewering turkeys and tweaking the noses of enemy powers must have sent a surge of patriotic pride through the readers.

Even as Kiwi polish went international, it received a setback in the home of the original kiwi; the product suffered the indignity of being denied its real name! The cause dates back to 1877, when household drug and chemical manufacturer Kempthorne Prosser & Co. registered the first ever kiwi trademark. Because of Patent Office regulations, this claim was to thwart the later marketing here of any household product—including shoe polish—under the same name.

Until the situation was rectified, the product was sold as Mirror, in a tin which was so similar to the real thing that surely the Patent Office twigged to what was going on.

Perhaps it was the unavailability of Kiwi that allowed its rival, Nugget, to gain a foothold in this country and become the generic term. Curiously, whereas New Zealanders tended to “nugget” their boots, in parts of England it was customary to “kiwi” them every morning.

[Chapter break]

New Zealanders would soon be back fighting overseas again, and this time there was little confusion as to who they were. The kiwi’s position had been secured by an aviary of commercial applications. As well as adorning Kempthorne Prosser’s KP Life Salts—”a daily glass is an investment in happiness”—the kiwi’s name and likeness graced a growing number of local products.

Kempthorne Prosser demonstrated its commitment to the bird by building it on a giant scale. Gold-painted, steel-reinforced kiwi graced the roofs of KP’s offices in the main centres. However, the prominence of the Auckland example, five floors above Albert Street, proved its undoing. In 1941, this bulbous bird was seen as a potential beacon to Japanese bombers, and was removed. It ended its days at the Meola Road tip.

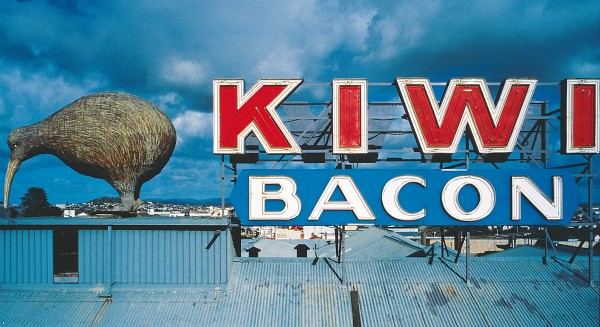

But Kempthorne Prosser had started something, for 20 years later New Zealand witnessed another multiple birth of giant kiwi. The origins of these quadruplets go back to about 1921, when Thomas Fenton of Palmerston North adopted the symbol of a kiwi beneath a tree fern for his line of cured hams and bacon.

This unusual association of pig and poultry proved effective, leading to the national dominance of the Kiwi Bacon Company. In the early 1960s the company installed rotating half-tonne steel-and-fibreglass birds above its four factories.

They became local landmarks, and it often took overseas visitors to remind New Zealanders just how unusual it was to have such a bird celebrated on this scale, not to mention the association with bacon.

So familiar were these kiwi that the observant public was still advising the Auckland office that its New North Road bird had stopped rotating years after it had been immobilised as an electricity-saving measure. In the 1980s, economic rationalisation reached further into the rasher business, and the birds themselves were retired. But these pioneering monuments to local enterprise live on, for Auckland’s has been gilded and given a new perch above a motel near the airport.

The kiwi further cemented its popularity with the people with regular appearances on postage stamps, coins and banknotes. For those who suffered from a shortage of the latter, hope arrived in 1961 in the form of the Golden Kiwi Lottery—which became an institution in its own right.

The versatile bird also got in behind local industry. To give the economy a boost after the Depression, the Department of Industries and Commerce launched a “Develop New Zealand” campaign, spearheaded by a pair of kiwi beneath the Southern Cross.

A decade later, the Manufacturers’ Association introduced the concept of “Well Made New Zealand,” teaming kiwi and Southern Cross with a pair of fern fronds. Despite its noble aims, the “Well Made” initiative is remembered more for the opposite: shoddy workmanship, which has left a lingering suspicion of locally made goods. Nevertheless, the Manufacturers’ Federation has stuck with the kiwi, and a stylised version continues to exhort the populace to “Buy N.Z. Made.”

With over 60 years’ experience in the workplace (notwithstanding its natural preference for the night shift), the bird has grounds to be wary of other symbols with ambition. In a 1985 attempt to update our image abroad, the Export Institute gave us the miha, variously described as a stylised snail and young ponga frond. Despite the fanfare of a Beehive launch, the new device literally curled up and died. The people had spoken: they were not about to have some fancy idea foisted on them. The kiwi was good enough.

Having proved itself on the battlefield, the kiwi was poised to demonstrate its ability in a slightly milder version of warfare: sport. But not, curiously, in what claimed to be the national game.

In the late 1880s, New Zealand dispatched a rugby team to Britain with a silver fern on their jerseys. Such was the success of that team that the fern has been enshrined in the hallowed halls of rugbydom ever since.

The choice of fern over fowl left the way clear for the kiwi to be adopted by rugby’s rival code, league, although when it came to portraying rugby at an international level, cartoonists called on the kiwi to switch allegiance. With an oval ball tucked under its vestigial wing, the fleet-footed bird was pitted against such regular adversaries as springboks, wallabies, lions and roosters.

For a visually challenged bird, the kiwi coped remarkably well, but its performance would soon be enhanced by a course of anthropomorphism. As the symbol for the 1990 Commonwealth Games, it even managed to overlook its stunted wings and take up weightlifting; ornithological accuracy had now yielded to the demands of sport.

If the kiwi’s popularity was due to an affinity between bird and people, both sides of this equation would change in the late 1980s. New Zealand realised it could no longer fall back on its traditional links with Britain, and a sense of autonomy began to emerge. In addition to suitable jargon, these winds of change brought us the brave new world of market forces and a level playing field. Some New Zealanders demonstrated they could cope very well with the challenge, as evidenced by the mirror-glass corporate towers rising on Queen Street. There was also a new confidence emerging on the sportsfield, and size didn’t seem to matter any more. When it came to the America’s Cup, for example, we proved we could foot it with the big boys.

This change of attitude called for a new symbol, and so a more gregarious and confident kiwi was unleashed. Raucous and strident, it replaced the self-effacing image of the past, and led the most fervent show of nationalism seen here since wartime. If the earlier kiwi had its beak in the ground grappling with a worm, the postmodern bird had it out in the open, sticking it to the opposition. The terraces rang to a new war-cry: “Give ’em a taste of Kiwir—which must have sent shudders through the natural world, at least.

The kiwi was now truly a bird of the times, having made the transition from ornithological oddity to symbol of an ambitious nation. As a barometer of national development, it had proved its adaptability, graduating from standing beneath tree ferns and the Southern Cross to accepting varying degrees of stylisation. In the mid 1980s, it went even further, cunningly amalgamating with the fern and the letters “NZ” to form the logo of a new national beverage, Kiwi Lager.

In 1940, the kiwi made a modest contribution to the nation’s centennial celebrations, but if it had expected some major symbolic duty during the big 150th birthday bash in 1990, it was to be disappointed. The top job of leading the nation forward went to a rank outsider, the kotuku (white heron). The kiwi, it seems, was yesterday’s bird, but it could take comfort from knowing that its influence on this country was something other birds could only dream about. And although overlooked in 1990, the kiwi may have a more prestigious engagement in its sights. In 2040, this country chalks up two centuries since the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi, and the kiwi may fancy being the bicentennial bird of the moment.

But if it gets the job, will the real bird be around to notice?

[chapter-break]

Having become synonymous with New Zealanders, the latter-day kiwi went looking for something more abstract: the culture at the heart of the allegedly typical inhabitant of these isles. The quest proved relatively straightforward, and, following the precedent set by Australiana, the quintessence of local culture came to be labelled kiwiana. There didn’t appear to be any other options; Zealandiana, for example, just didn’t sound right.

Kiwiana as a term was coined in the late 1980s, several generations after it had infiltrated the villas and bungalows of New Zealand. It is now in the dictionary, defined as “any of many collectibles” and “items redolent of New Zealand life and culture.”

Because the phenomenon preceded the term, we might wonder when the first of these redolent items actually appeared. An early contender, with more than a dash of local character, was certainly Taniwha soap. A by-product of one of the country’s defining features, the meatworks, its very name conjured up mythical monsters, while the label displayed a bevy of topless mermaids lathering up against a backdrop of smoking volcanoes. Every home had this self-proclaimed “golden bar of purity,” and whether we cringe now or not, it was a mirror of the times.

Something of a belated cultural discovery, kiwiana is frequently associated with post-World War II New Zealand, and the 1950s in particular. This period is still within the collective memory, and was responsible for a substantial stock of what now passes as kiwiana. Plastic sandals, the black bushman’s singlet, Edmonds “Sure to Rise” baking powder and cookbook, fibrolite, paua-shell ashtrays, school milk, Jeyes toilet tissue (akin to waxed paper, and about as efficacious), sandsoap, Bushell’s coffee essence, corrugated iron and L&P are a few of the many items that today are venerated as kiwiana.

They were austere times; the country had either to make do or go without. Pragmatism found its expression in the robust range of sand-cast Fun Ho! toys and the indestructible Crown Lynn New Zealand Railways cup. Crown Lynn also provided something a bit more ornamental for the nation’s mantelpieces and china cabinets: the once ubiquitous swan and kiwi vases.

In addition to supplying the name, the natural world has also contributed to our stock of kiwiana. It gave us the Chinese gooseberry, which, with a bit of local ingenuity, was transformed into the kiwifruit (shortened overseas to just “kiwi”). The Buzzy Bee is also part of the cultural entourage, although some say it was developed from an American idea. But even if it was, at least our version was turned out in three dimensions, as opposed to the flat foreign pretender.

The kiwi has now given New Zealand almost a century of solid service—pretty good for an icon that has never been granted official status. But for how much longer can we count on its support? In recent years the country has come to the sad realisation that the bird is marching up the endangered list. Quite apart from what the kiwi itself feels about this deplorable situation, we might ask what effect the bird’s demise would have on the self-image of New Zealanders.

If the worst happens, the kiwi connection might be too solid to be overturned. Our affinity with the bird is strong because it has developed slowly, from the ground up. And besides, national symbols do not have to be real—it’s been a while since the British lion was suzerain over Salisbury. Even so, there are times when the kiwi must wonder which side we are really on. The logo for the New Zealand Festival 2000 in Wellington has raised eyebrows, consisting as it does of a kiwi propelled by a nikau palm apparently inserted in its rear end. The bird can only shrug—if such a gesture is possible under the circumstances—and take consolation from the fact that controversy is the price of popularity.