The next spillover

The emergence of a new coronavirus is not a question of if, but when and where—and a new study has answered the latter by mapping global regions most likely to produce the next outbreak.

The research used horseshoe bats as a model, because they carry several coronaviruses from the same group that caused COVID-19, SARS, and a pig disease known as SADS. The study then connected the dots between several details: where the bats lived, forest fragmentation caused by expanding farmland, human population growth, and increasing numbers of livestock. Where all these things overlap, they “form a nexus where you might have really high risk”, says David Hayman, a Massey University infectious disease ecologist who was part of the international research team.

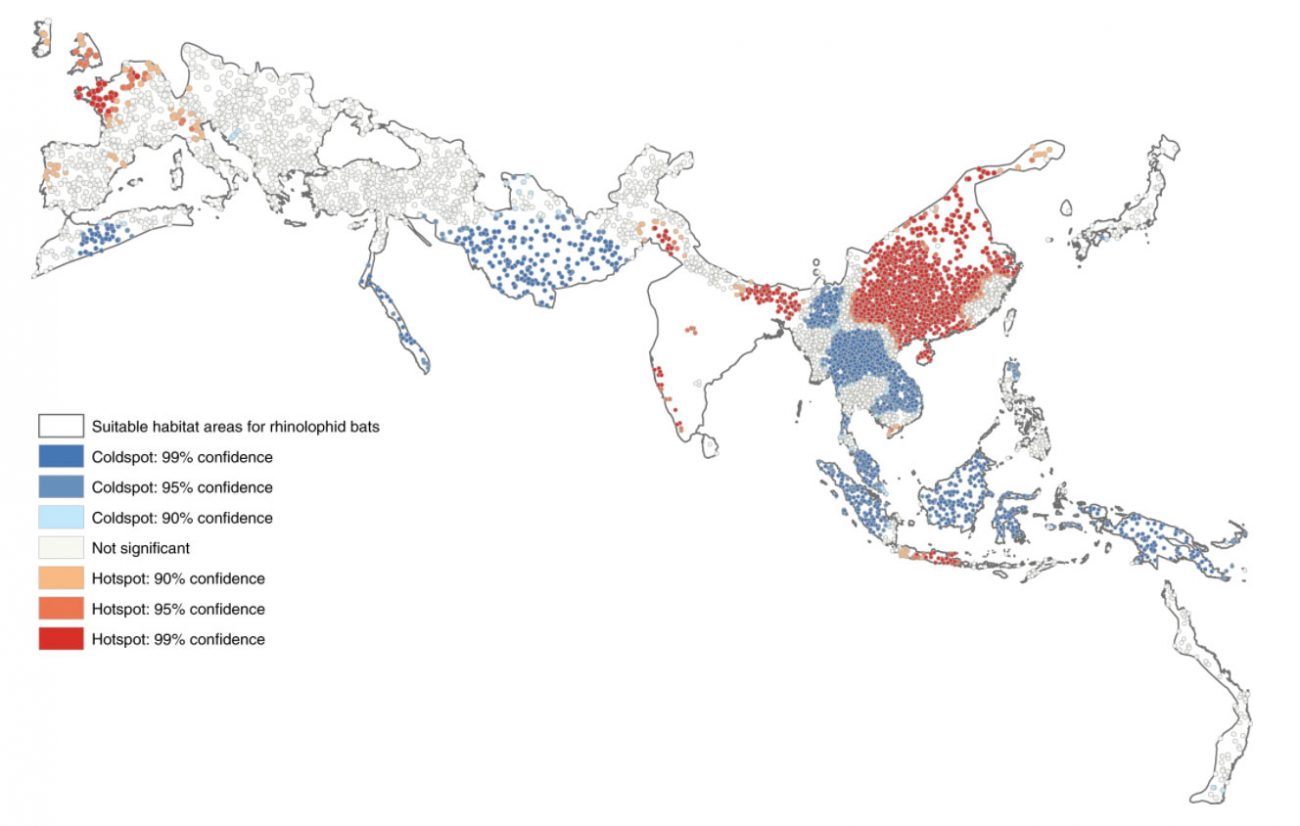

The map—a swathe of horseshoe bat habitat from Spain in the west to the coast of Australia in the east—identifies China as a global hotspot, as well as Bhutan, east Nepal, northern Bangladesh and Thailand, all places where the next spillover event is most likely to transmit a virus from animals to people. In host animals, such viruses usually cause no harm; in other species, such as humans, the viruses can lead to severe and highly contagious disease.

We know that if people encroach on wildlife, the risk of spillover increases, says Hayman. Our best chance of preventing such animal-human transmissions from growing into major outbreaks is to increase disease surveillance in high-risk areas. Heightened surveillance could also help contain outbreaks of existing spillovers, such as Ebola, which now re-emerges almost annually.

But with a viral universe that likely includes millions of different strains, we need to think beyond pandemic preparedness. “If we really want to reduce the risk, then we need to look at the bigger things—what is causing forest fragmentation, and should we be putting another intensive farm with livestock in this area,” says Hayman, “because the same things that increase the risk of disease emergence also contribute to biodiversity loss and climate change.”