The great bird nerds

Around the country, Birds New Zealand branches are trying to motivate their members to fill in one more observation list, while keen birders are ticking off grid squares, aiming for high scores. They’re working on the Bird Atlas, the biggest-ever citizen-science project on our shores.

11 binoculars and two tripod-mounted telescopes are pointing at the mouth of the Tokomairaro River, near Milton in Otago. A chorus of voices categorises the moving and still splotches in the distance: “Forty terns.” “Five black bills.” “A variable oystercatcher.” “Two fantails. Do fantails count?” They do.

Someone worries what the sleepy families, tucked inside the tiny houses along the gravel road, will think of a group of outsiders with binoculars pointed everywhere. “Oh, they know,” says a seasoned birder. “They see these nerdy people and they know we’re looking for birds.”

This is a monthly excursion for members of the Birds New Zealand Otago branch. And it’s much more than a chance to gawk at birds. Birds New Zealand (previously known as the Ornithological Society) is the lynchpin of our country’s biggest citizen-science project, the New Zealand Bird Atlas. These nerds are collecting data.

The bird atlas began in 1969, an ambitious project to map species and abundances on a national scale. The country was divvied up with a grid, and birders were rallied to observe birds in each square. Ten years later, they’d ticked off all but four per cent of the squares. And not just once: each square had been visited an average of five times. The birders kept written lists of the species spotted in each, which were then compiled into a series of distribution maps—a national bird atlas. The survey was conducted again 20 years later, with similar diligence. We’re now halfway through round three: data collection kicked off in June 2019 and will end in 2024.

The data will be available on request to researchers and decision-makers, and to regional councils, to help them better understand the state of the environment in their area. It can help officials assess the likely impact of land-use change—like roading projects or housing developments.

It’s still amateurs and huge hours of voluntary work driving this project, but at least the technology has changed. Today, a birder in a black puffer jacket and multi-pocketed pants transcribes the human chorus into the eBird app on her phone, listing all the birds identified in this location over a certain amount of time (in this case, 12 minutes). Meanwhile, her phone records the GPS location, date and time. The app then gathers this information and adds it to hundreds of thousands of other completed checklists, which are accumulating into the current atlas.

Richard Schofield steps aside from the larger of the scopes. He is wearing khaki shorts, a style he wears right through winter. “Anyone wanna look at some gulls?” As newer members look through the scope, he explains how to tell the difference between black-billed and red-billed gulls. As well as the obvious, the black-billed gull has a lighter plumage, long elegant neck and slender body. The red-billed gull has bright-red eyeliner. Both species are in decline.

Schofield has been a birder for almost five decades. He’s lived in New Zealand for about 20 of those years and written well-used guides to our birds. In these circles, he’s an almost heroic figure. He is known to count birds—accurately—while cycling. For the atlas, he is this region’s recorder and reviewer, meaning that as well as guiding his flock of birders, he scrutinises their work. Unusual checklists have to get past him before being added to the atlas. “He makes us submit photos, because he doesn’t believe us,” says one woman. Schofield responds: “It’s not that I don’t believe people. I believe people remember what they think they saw.” He has corrected misidentified species plenty of times from photographs.

Today, everyone’s keeping a special eye out for kotoreke, the marsh crake. Adults weigh only 30 or 40 grams—about the same as a single sock—and live deep in estuarine and freshwater reeds. They’re known for being one of our most secretive birds, and they, like the gulls, like so many of our birds, are declining as well.

This group is 13 strong, a mix of long-standing regulars and new faces. They chatter about birds and counting methods as they tick off a fast-moving flock of terns. Consensus: 40. While group atlasing trips gather strong data and help less-experienced atlasers to get the hang of things, it is only in Otago where they happen regularly. Elsewhere, it’s been hard to muster the numbers. The majority of checklists are submitted by individual observers.

Most here today also contribute independently. According to the Atlas Top 100—a continually-updating ranking system on the bird atlas website—Schofield has knocked off 6134 complete checklists. “My wife thinks I’m obsessed,” he says. “I prefer dedicated.”

It isn’t until the sun is setting that the final checklist is completed. No kotoreke, lots of fern birds and skylarks.

From a wetland, the birders watch the sun set behind hills dotted with rabbits, flowering gorse and sheep. It’s been a 10-hour day. “We’re motivated to want to help the birds,” says one woman. “That’s at the heart of it.”

These monthly atlasing trips are tactical. They target squares where checklists are lacking, or where there are “cryptic” species—birds you’d think would be present, but haven’t been formally spotted yet. The atlasers feel driven to keep looking for these species and get them tucked safely onto the grid, because birds unseen and unheard become a zero. And if there’s a zero, there’s nothing there to protect, to make planning and council decisions around, to control predators for.

[Chapter Break]

Sue Frostick considers herself “not a very intrepid atlaser”. Still, on a rainy Thursday evening in late July, she is scrambling up muddy banks well after sunset. Tonight, she is canvassing the “airport square” or AD67, one of the less-surveyed squares in Manukau, Auckland. It sits on the eastern edge of the Manukau Harbour, but instead of heading to the shore, she sticks to the industrial zone.

When Frostick retired from her job as a healthcare assistant, sitting at home doing nothing didn’t appeal. A guided bird walk at Māngere Bridge piqued her interest. Looking through a telescope at the wrybills, oystercatchers and royal spoonbills on the shell bank, she realised there was so much to learn, and so much to do. She picked up a pamphlet. Three years later, she’s the regional recorder and atlas co-ordinator for the South Auckland branch of Birds New Zealand.

On top of that admin, Frostick tries to spend two or three days atlasing each week, with a particular focus on cryptic birds and neglected squares. Tonight, she’s looking for ruru.

Nocturnal counts are under-represented in the atlas, especially during winter. Understandable: no-one’s getting paid for this, and it’s cold, dark and easy to get “skunked” (not find any birds). But a zero is a valuable number, too—it’s essential to know where birds aren’t.

Some birds don’t make it easy. As well as the cryptics—often shy birds, such as the kotoreke—there are the flyers, which move overhead in a blur and are gone before you can consult any sort of guide. Some common species of duck are almost indistinguishable due to interbreeding (see feature, page 50). Often, a bird is nothing but a song, or a call. Frostick’s been training for this, downloading recordings from the Digital Encyclopaedia of New Zealand Birds and loading them into her car stereo. Her ears are attuned to pitch and melody—when she isn’t birding, she sings bass in a choir. Still, she says she confuses the blackbird’s song with that of a thrush, and needs to confirm these by sight.

Lately, Frostick has had little time for choir—it’s all been going on atlasing. “This is my turn to contribute,” she says. She pulls up under a row of pines. The wind whips at the wire fence. After five minutes of nothing but rain and wind, Frostick pulls out a torch. She walks along the fence line, sweeping the trees with light. Up the trunks, along the branches, out to the sparse needles. A truck hurtles by.

[Chapter Break]

It can be tricky to determine whether citizen scientists are experts or fumblers. Many, like Frostick, don’t have a relevant university degree, often considered a badge of competence. But what they do have is experiential knowledge. This can be harder to quantify and to trust. It can also be a powerful tool.

On the upper slopes of Mōpānui, near Dunedin, moss and lichen cling to small outcrops of stone. Here, Oscar Thomas sits and listens. Birdsong lifts from the bush. This is Thomas’s third atlasing spot today. First was the Aramoana saltmarsh, where the viewing platform was scattered in little crab legs and claws, the remainders of kōtare lunches. He recorded 24 species there. Next, the sea wall that extends north-east opposite the royal albatross colony. Fourteen species.

At 24, Thomas has been obsessed with birds since a primary-school trip to the island sanctuary Tiritiri Mātangi. He made himself a citizen scientist. Alongside his bird watching, he’s taught himself photography, slowly improving and upgrading his kit. (He says his photos didn’t get any good until he was 15.) Two years ago, he published A Naturalist’s Guide to the Birds of New Zealand. A friend of his says that sometimes, talking to Thomas is like talking to a guidebook.

Now, he’s about to cap it off with a degree, via the University of Otago, in zoology and ecology. In 2023, as a postgrad, he hopes to study the breeding behaviour of Otago shags. Not because they are his favourite—that would be the North Island kōkako, with its haunting song—but because shags are comparatively understudied. His ambitions are firmly located in New Zealand. It’s these birds, these ecosystems, this land he cares about.

When Monica Peters returned to university as a mature student, it struck her that people don’t need a science degree to do valid science. Often, practical projects aren’t particularly specialist or out of reach. As one citizen scientist reminded her, “It’s not as if we’re dipsticks.”

This is not to say that science can be done willy-nilly. Peters emphasises that citizen scientists need processes, practice, skills and tools in order to be reliable. They need to feed their data into frameworks—like the eBird app—which standardise the observations and measurements. “That’s really vitally important, particularly for a national study,” she says. And they must have resources and access to experts. So, three years ago, to help make all this happen, she co-founded the Citizen Science Association of Aotearoa New Zealand.

Peters saw that harnessing citizen science could extend the reach and possibilities of science, especially in the field.

Citizens—that is, people—are spread all over the place. They also know things visiting scientists don’t, such as exactly where the local bittern tends to pop up during one’s early-morning run.

The bird atlas is an example of the sort of citizen science she’d like to see much more of. But it’s rare: projects on this scale are resource-hungry, and difficult to pull off. Peters calls it a “major enterprise”. In contrast, the community environmental space she works in is fragmented. Small groups focus on their own local projects. Many are important and effective, but it’s difficult to bring data together to see greater trends or patterns.

It’s important to remember that using citizens as scientists does more than extract their labour. Volunteers learn, become a part of something, and enjoy each other’s company. They can also develop a relationship with their environment.

[sidebar-1]

Time with Thomas is punctuated by long moments of attentive silence. He pauses, and tilts his face towards the tips of the trees. He can hear a male tomtit singing, but seeing it is always better, because it may be with a silent female. For Thomas, birding provides a counter to the stress of life; an attunement that is meditative.

From his perch, Thomas can see into Orokonui Ecosanctuary. He hopes to spot a kakaruai/South Island robin. They have done so well inside the fence that a healthy population has spread into the surrounding bush. It’s easy to forget that the atlas can measure not only what’s going wrong, but also what’s going right.

[Chapter Break]

It’s 7:35pm on a Tuesday, deep winter and halfway through a week-long barrage of rain. The South Auckland branch of Birds New Zealand has been meeting monthly at the Papakura Croquet Club for as long as anyone can remember. People used to spill out of this small room during meetings, but today, there are empty chairs in rows. The Papakura Pipe Band distantly soundtracks the evening.

Eight birders are quietly seated facing the front of the room. Among them, Sue Frostick sits with a straight back, looking through papers on her clipboard. She taps her laptop, connected to a projector pointing at a pop-up screen. Around the room, there’s a lot of forest-green polar fleece, and a couple of woollen beanies, one with the Green Party logo embroidered on its front.

“Well, I don’t know where everyone is but we better get started.” But wait. Here comes a man in stubbies and bare feet, followed by a grey-haired lady in a pink coat. From one of the many shopping bags strung on her hands she pulls a pair of sheepskin slippers. “I know what it’s like in here,” she says, not minding the hush Frostick is trying to maintain. She’s been a member since 1979.

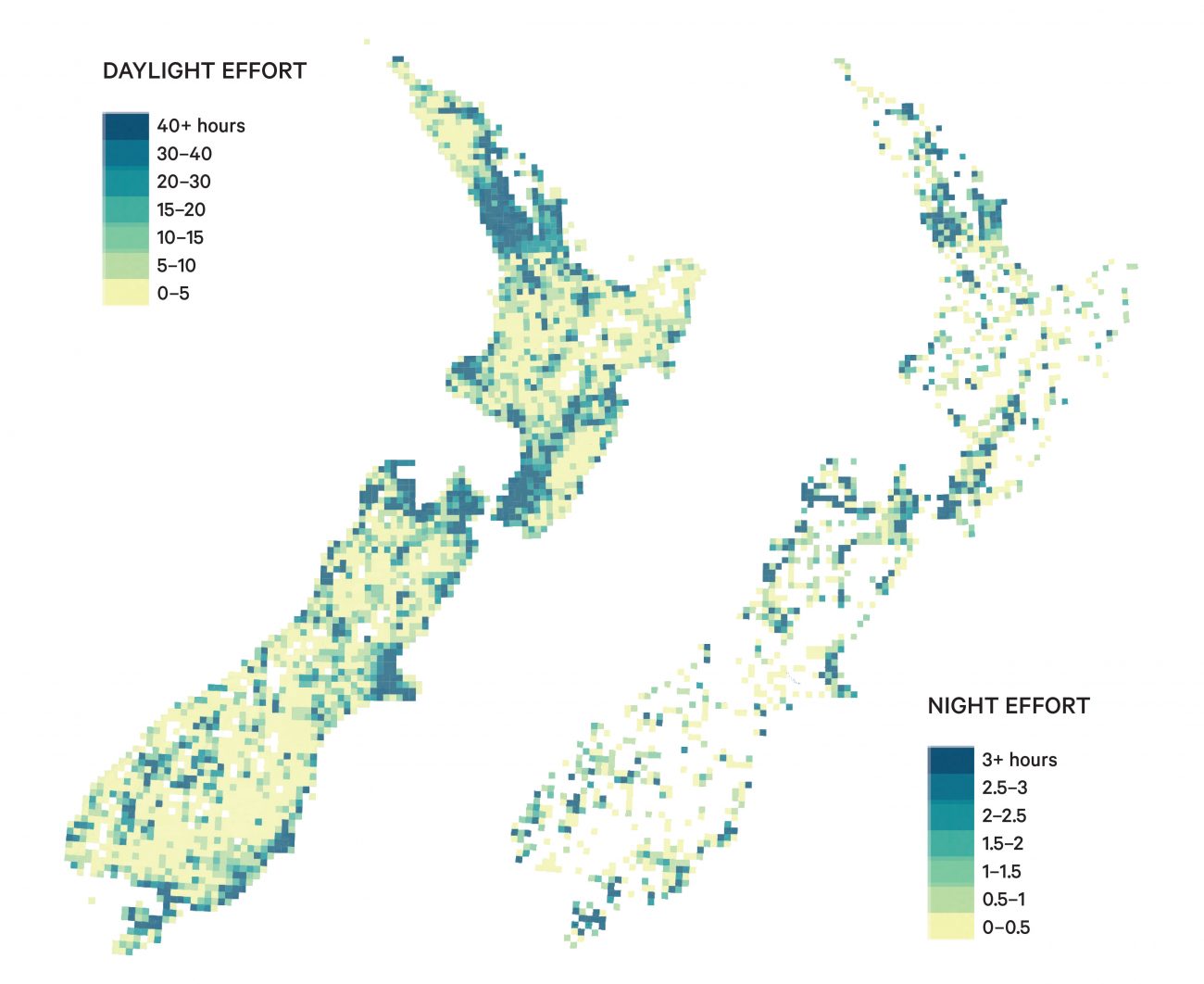

There are several matters on tonight’s agenda, one of which is an update on their atlasing efforts. Frostick is trying to encourage nocturnal counts. It isn’t great news. “We haven’t had nearly the response we had during Covid,” she says. “I suppose people have better things to do.”

She projects a map and zooms into certain squares, ones which aren’t far away and wouldn’t be too hard to access. “That road is full of roadworks,” somebody says. But there is also a walkway around the coast, pointed out on the projection. “That at night? No thanks,” says a woman who’s been clicking her pen, taking notes for the monthly newsletter. To the west, there are undersurveyed squares all around Waiuku. “Where’s Ted?” someone asks from the back of the room, “he could certainly go out and have a listen.”

Frostick changes the map. Purple squares show where ruru have been observed, almost covering the whole region. “Oh, wow, they’re doing well,” comes from the back of the room. But there are a few conspicuous gaps—like dead pixels on a screen. Frostick zooms in on one. It’s a coast, the southern curve of the Firth of Thames. “The unloved square, sandwiched between two good birding roosts,” says the man in stubbies. Another square is pointed out, at the base of the Coromandel Peninsula. “That’s the Thompsons’, isn’t it?” asks the newsletter writer. “Shall I ask the Thompsons at the farm to do a count?”

In her next move, Frostick gives away the fact she’s spent hours poring over these grids. She has compiled a list of “missing” birds, or cryptics. They’ve been matched up with squares people could scan for them, squares with suitable habitats. The birders are somewhat incredulous at the carefully prepared spreadsheet.

“Where are you going to find a redpoll?” asks one member. But from the back of the room, a lifelong birder on his third atlas says, “You have to know where to find them, know their call.” Sometimes, he says, redpolls insert themselves in flocks of goldfinches. You have to look for their reddened head. He sees gaps in the atlas, too. “The atlas isn’t turning up good swamp birds. Which is something I could do, but I don’t.” He gets tired now; this atlas isn’t the same as the previous two. “I do one thing,” he says, “and I get tired, so I have a cup of tea and sit down.”

At the end of the meeting, there’s carrot cake and tea. Everyone gathers in the kitchenette, and brown Luminarc mugs are passed around. Talk turns to the personality types working on this citizen-science project. Some are simply obsessed with birds. Others are considered “square bashers” for the sheer number of squares they cover in what seems to be record time.

There are old gurus, and young energetic birders they sometimes feel tired just listening to. There are long-distance trampers, urban backyard birdwatchers, and a few who’ll spend hundreds or thousands of dollars to get to remote islands, hoping for their first glimpse of a rare bird. There are long-time birders who remember counting birds from the school bus, who jot their observations into a Warwick 3B1 notebook tucked into their pocket.

When the cake is finished, the members clear out, wishing each other goodnight. Outside, it is dark and quiet. The man in bare feet walks home, just up the hill.

[sidebar-2]