The fate of the Nino Bixio

On August 17, 1942, an Italian prisoner-of-war ship carrying Allied soldiers was torpedoed off the coast of Greece. Crammed into the forward hold were 174 New Zealand servicemen. One of them was Ben Stanley’s great-uncle.

As the cargo ship approaches Port Ahuriri, a small crowd gathers on the wide concrete landing between the storerooms and the water. Among them are Wesley and Ivy Stanley, both in their late 50s, clasping each other’s hands.

It’s the summer of 1955. The ship is carrying commercial goods, but that isn’t the reason Wesley and Ivy have driven into Napier from Clifton Beach to see it. During World War II, it bore a human cargo.

Wesley is a warden at the Cape Kidnappers gannet colony, a quiet bloke who raises his voice only when people act the fool. Ivy is more assertive and outspoken, but they’re both silent as the ship nestles against the wharf, looming over them. It has an Italian name, spelled out in tall white letters on its side: Nino Bixio.

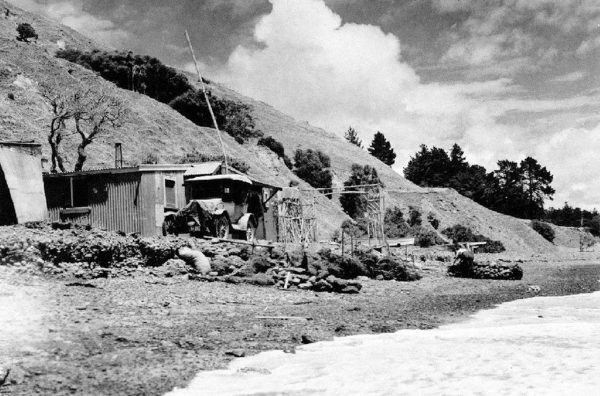

They remember the day their boys signed up to serve. Douglas and Frederick stood for photos at home at Clifton Beach, in front of the four-room house Wesley had built for them beside the water.

Douglas was dressed smartly—a cream jacket and pants, a wide chequered tie. He’d always been reserved, like his father. His currency was a hard day’s work—it was the Stanley way. When the war broke out, he was a shepherd up at Wairoa, with a team of working dogs he loved immensely. Frederick was living in Hastings, where he was a baker. In the photos from that day, he’s tall and doleful, dressed in a plain shirt—no jacket and tie for him.

They were proud to be off to war. Wesley remembered feeling the same way in 1914. He had an idea of what was in store for his sons. He’d landed at Gallipoli, and after four months’ fighting, had been shot in the neck on the summit of Chunuk Bair, and shrapnel sprayed down his back. He’d crawled down the mountain to safety.

Douglas and Frederick shipped out on the same day, but they were sent in different directions. Frederick joined the New Zealand Divisional Artillery, then became a cook on HMNZS Achilles. Douglas was assigned to the 25th Infantry Battalion of the Second New Zealand Division, and embarked for the Mediterranean where the 25th set up camp near El Alamein in late June 1942. On July 1, an attack by German forces began what was to become a month-long battle for control of Egypt’s ports.

But for Douglas, the First Battle of El Alamein ended three weeks later. On July 21, the 25th mounted a late-afternoon assault, capturing the eastern side of the strategically located El Mreir Depression. But promised British armour didn’t arrive overnight, and at dawn, the 25th was overrun by the 5th and 8th Panzer Regiments. About 1700 Allied men were captured and sent to a prisoner-of-war camp in Benghazi, on the coast of Libya. Jim Henderson, a lance-bombardier from Motueka, who later wrote a book about the battle and its aftermath—No Honour, No Glory—described the camp as a “bare and windless rocky valley, hot as an oven and lorded over by unsanitary, trigger-happy Italians”.

Finally, orders arrived to ship the captives to Italy. They were divided by surname and issued with identification cards: A to L received a red card for the Sestriere, while M to Z got a blue one for the Nino Bixio.

As they boarded, Northland serviceman Leo Wakelin told his mate Jack Richards: “When we get out of this, we’ll go to Whangaruru and have the biggest feed of crayfish you ever dreamed about.”

Two days later, he was dead.

[Chapter Break]

The MV Nino Bixio was almost brand new. Named after a general from the 1870 unification of Italy, it had been commissioned in Genoa nine months earlier. Still, there was hardly enough room for 2921 POWs.

The captives were destined for Brindisi, a port on the heel of Italy’s boot. But the Nino Bixio’s captain, Antonio Raggio, decided to zig-zag across the Mediterranean, turning a day’s journey into three. Royal Navy submarines were hunting ships bound for Italy, so Raggio would pretend to sail for Greece.

On August 16, flanked by two destroyers and two torpedo boats, the Sestriere and the Nino Bixio left Benghazi harbour. The ships were unmarked, flying neither a red cross nor a white flag, the signals for wounded servicemen or prisoners of war.

Crushed into the forward hold were about 500 of the prisoners, including the New Zealand contingent, “packed tight as a swarm of bees”, said Henderson.

It was late afternoon at the height of the Mediterranean summer when the convoy set sail. The foward hold was standing room only and the air was heavy and stifling and foul.

“All I did all night was sit down on my haunches and stand up. Sit down, stand up. Sit down, stand up,” said Ron Yates, a serviceman from Tauranga, in a 1960s radio documentary, Prisoners of War.

The following day, whispers began filtering through the ship that there was an Allied submarine in the area.

Out in the deep, the HMS Turbulent was prowling. Its captain, John ‘Tubby’ Linton, was a Welshman who played rugby for the Royal Navy. He would later be posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross for sinking 81,000 tons of enemy shipping.

By mid-afternoon, the Peloponnesian coast of Greece was visible from the deck of the Nino Bixio. About 3.30pm, Linton gave the order to fire.

“I had a premonition it would happen,” said Yates. “I was sitting there and, all of a sudden, everything just seemed to go cold around me. I felt black wings beating around. I knew it was death, but above me there was a white light shining. I felt that though there was death all around me, it wasn’t going to hurt me.”

The first torpedo struck the Nino Bixio’s engine room. The second clipped the rudder, disabling the ship’s steering. The third smashed into the forward hold.

The explosion killed dozens of men in an instant, vaporising them. Then seawater surged into the hold through a ragged hole two storeys high, throwing men around like garments in a washing machine. Hatch covers and steel beams collapsed into the turmoil.

Of the chaos, Henderson remembers “swirling bits and pieces of bodies. Screams. Terrible cries for impossible help.”

Some were spared. Charles Watkins, originally from Wellington, was playing cards on the forward hold’s upper deck and climbed to safety, he later recalled. Yates was thrown above the ship by the explosion.

“I had a feeling I was up in the air but I couldn’t see,” he said. “I was in a grey cloud and all I kept thinking was, ‘Which arm? Which leg?’”

He landed on his side on the deck, suffering a knock to the back that would bother him for the rest of his life.

The sea was full of bobbing heads. Some captives had been sucked out through the hole in the hull, while others had leapt overboard, believing the ship was sinking.

Survivors still on the Nino Bixio began throwing ropes to them. One man pulled his body up hand over hand, then collapsed on deck, both of his legs missing. Another man was found in a coffin of steel plates that had curled around him as the sides of the ship split apart.

The Nino Bixio glided on without power, slowing and lowering in the water. Behind her, Henderson saw “a pitiful spreading wake of debris and drowning men that finally reached almost as far as the eye can see”. The two destroyers cut through the human wake, releasing depth charges, but the Turbulent eluded them.

A few of the survivors in the water, clinging to makeshift rafts, would be rescued later. Most would die.

Somewhere amidst the carnage was the limp body of my 23-year-old great-uncle.

[Chapter Break]

When news reached home that Douglas had been captured at El Alamein, Wesley and Ivy were thrilled. Surely it meant he was safe.

Douglas had already made a plan for after the war. He’d save up for his own farm, and he’d already talked with his youngest brother, Max, about going in together. Max idolised Douglas—he was only 11 when his older brothers left for the war.

Clifton Beach locals would tell this story to our family years later. The day in 1942 that Ivy learned of Douglas’s death, she walked down to the beach.

There, she howled with grief for her lost son. Her wailing was so loud that it could be heard in Te Awanga, two kilometres to the north.

[Chapter Break]

After the attack, the Sestriere made for Brindisi at full speed, leaving the Nino Bixio floundering. Though severely damaged, it did not sink, but was towed into Greek waters and beached near Pylos. While able-bodied survivors buried the dead, Captain Raggio visited the wounded in hospital, bringing gifts of cigarettes, grapes and sweets and “sympathising in uncertain English”, said Henderson, “but pointing out that war is war and he too has lost good men”.

Had Tubby Linton known the convoy carried Allied prisoners? He wouldn’t live to answer the question. Seven months after the attack on the Nino Bixio, the Turbulent was sunk off the coast of Italy, all hands lost.

Yet the Nino Bixio had no markings of a POW ship, and with its four-ship naval escort, there’s every chance Linton thought he’d found an Italian troop transport.

“Naturally, when they see a ship like that, they must think there’s something on it,” said Yates.

War is war, as Raggio told those New Zealand survivors in Greece. One order from a submarine captain begins a chain of events that leaves my great-grandparents clinging to each other on a Napier wharf.

Neither Frederick nor Max joined their parents to see the ship that carried their brother to his death. Frederick had become a sexton at the Hastings crematorium, while Max was working on a station at Kereru, west of Hastings.

Max was doing his best to bring to life his older brother’s dream. He was a shepherd, like Douglas had been, and he’d married, become a father. His first child was named Douglas. His second was David, my dad.

Growing up on a farm on the Napier-Taupō road, I read book after book about New Zealanders at war, but it was my great-uncles’ experience I thought of most. It’s been 75 years since the attack on the Nino Bixio, but I can still sense the forces that shaped my family and our identity. I think of the pain my grandfather carried with him for his lost brother, with whom he never had the chance to go farming. I think of the agony that propelled my great-grandmother, wailing, to Clifton Beach.

I think of a hot summer day off the coast of Greece, and my family’s all-too-familiar war story—another one where a young man, full of promise, never comes home.