The Deep

Below the thrashing surface, the depths of our oceans are a wonderland of creatures designed to a very different pattern from anything found on land. In the spirit of the first explorers, French curator Claire Nouvian embarked on an expedition to collect underwater anomalies from our own backyard and exhibit them in the halls of Europe.

The deep hides its secrets well. Like peering into Narnia through the crack in a wardrobe, scientists can only ever catch occasional glimpses of what goes on hundreds of metres beneath the sea; either from submersibles, remote cameras, or by studying the strange fish that turn up in commercial fishing nets. Strange fish indeed. There are animals here that resemble the fevered depictions of alien life from sci-fi movies; undoubtedly many of them have provided film directors with their inspiration. Some look as though they’ve been stitched together from the leftovers of other fish, like some kind of celestial prank. There is a fish called the blobfish that simply looks like a blob. Really.

These animals come from a high-pressure, dimly lit, and relentlessly cold environment which has produced idiosyncratic and often bizarre anatomical responses: disproportionately large eyes, disproportionately large teeth, feather-like fins, parrot-like beaks and bioluminescent lamps.

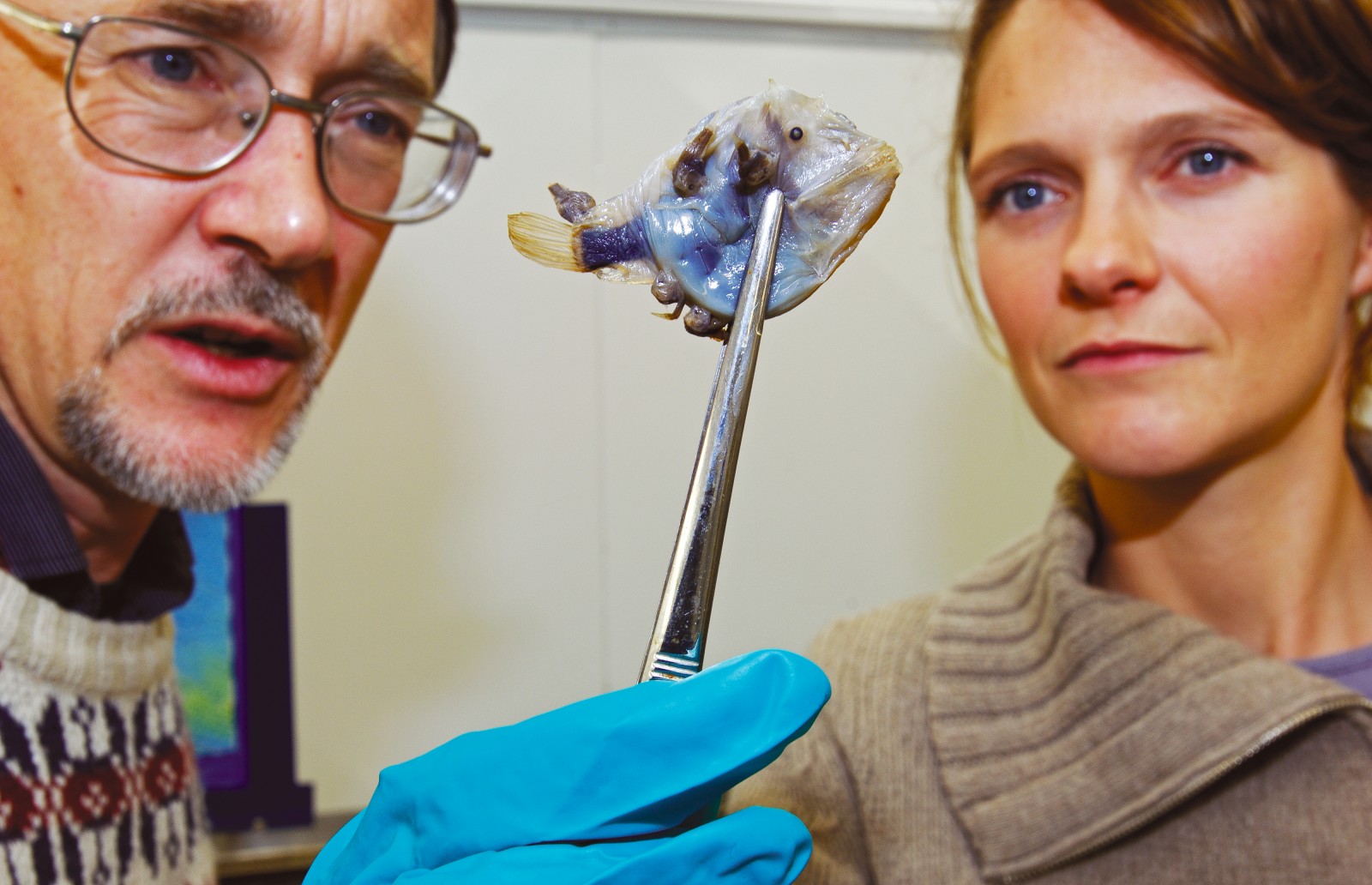

It was just such deep-sea creatures that captured the attentions of Claire Nouvian, a French photographer, film maker and author who recently joined New Zealand scientists on the research vessel Tangaroa, specifically to collect the weirdest deep-sea creatures she could get her gloves on. Injecting her creatures with formalin, she packed them into boxes, and shipped them back to Paris—a kind of contemporary equivalent of 18th century biologists collecting novel animals from around the world for display in the museums of Europe.

“There are so few research institutes doing deep-sea work in the world,” says Nouvian, when asked what brought her to these parts. “Of course, New Zealand has deep waters all around it with various chains of seamounts and a tremendous diversity, so I was hoping to get a good sample of species. But the reality exceeded my wildest dreams.”

Nouvian joined NIWA staff on their annual trawl survey of the northeastern Chatham Rise in July last year. Such surveys are aimed at assessing orange roughy stock. Deep-sea research in New Zealand is invariably funded by, and therefore tied to, the fishing industry. But any survey trawl also hauls up creatures that swim with the orange roughy and are usually lumped together, rather disparagingly, as bycatch, but are all marvels in their own right.

Nouvian couldn’t believe her luck. After three weeks almost every weird and wonderful species on her “wish list” had been collected and preserved in formalin. “New Zealand waters are biblical.”

Biologists on Tangaroa say that Nouvian’s enthusiasm managed to remind them that the strange fish they encounter every day on these surveys really are also fascinating creatures full of unsolved mysteries. Sometimes, after seeing hundreds of them, you can forget. Says NIWA scientist, Matt Dunn: “I remember one of the first trips I did and getting really excited about seeing a viperfish. Even seeing my first orange roughy was really exciting, but by the time you’ve seen 10,000…having someone like Claire on board reminds you that the animals you’re seeing really are quite exceptional.”

Taxonomists dissect these creatures looking for anatomical clues with a view to placing them on the tree of life—connecting them up with their genetic ancestors and classing them into specific taxa. But understanding how they behave, or trying to provide a behavioural explanation for their physical appearance, isn’t quite so simple. What is the point of that feather-like fin? Or that retractable growth jutting out from between those eyes? Why the big nose? The long face? Why, by the way, are orange roughy orange when, in the dark, all fish are grey? (Actually, biologists have only recently realised that, way beneath the waters, some orange roughy are actually white. Nobody yet has a clue yet why, because by the time they are hauled to the surface, they are orange.)

[sidebar-1]

Scientists really know more about nematodes than they do about deep-sea fish. They have to to draw most of their conclusions from netted samples with scant observation to guide their imaginations. It is prohibitively expensive to observe deep sea organisms in situ and when it is possible, it tends to be from the vantage of a large, bulky, brightly-lit and extremely intrusive observation device that has turned up in this dark and quiet place. Scientists joke that only the slow and infirm are ever caught on camera. “It’s like driving around the Serengeti in a tank with all the lights on,” says Dunn. “It’s not a very subtle way to creep up on something.”

Nouvian, fascinated by the behaviour of deep-sea creatures, has researched them for years. She probably knows as much as anyone about them and that, she says, is “practically nothing”. Take a jewel squid, for example, with its single large bulging eye and another smaller one embedded in its body. “There are as many suggestions about this peculiarity as there are scientists pondering the problem,” she says. “One of the most widespread beliefs is that it swims at a 45° angle with the big eye scanning the faintly-lit waters above it and the small eye scouting the dark waters beneath.” But it’s only speculation, she says. “The truth is that no one knows.”

Dunn’s example is a type of male chimaera, a deep-sea shark which has, he describes, a retractable thumb in the middle of its forehead, at the end of which is a fixture that resembles a small ball of Velcro. “That’s really weird!” he says. “Only males have it, so presumably it’s something to do with sexual reproduction. Maybe it stimulates the female or attracts her. But we really don’t know what it does with it. It’s just bizarre.”

And then there’s the anglerfish. Females of the species (featured on page 97) grow to around five or six times the size of males, and are usually found with a few males attached—fused, actually – to their flank. Dunn: “So they become a parasite, a permanent fixture on her side.” And why? “The idea is that females are so few and far between that when males find them, they don’t let go”, he says. At least, that’s the idea based on the biological imperatives in which everything usually comes back to food and sex, but of course it could be the result of something else altogether. “I’ve only ever seen about four or five of them but they’ve always had a male attached,” muses Dunn. “So it obviously works quite well.”

Unsurprisingly, Dunn would love to know more, or at least have the money to find out more. If he had his way he’d leave a deep-sea camera on the ocean floor for several months, so that the fish get used to it and go about their normal business in front of it. But research in New Zealand is usually aimed at assessing the impact of human behaviour on commercial fish species, rather than fish behaviour for fish behaviour’s sake. “It was the fisheries that stimulated the research, which is a good thing, but the focus has been on commercial species… which is why knowledge about all those other species is so slow in coming.”

Still, every trawl survey yields its surprises and adds more small details to the slowly accumulating body of knowledge. This trip, for instance, involved deeper sea trawls (1700 m) which netted a number of female black slick-heads several times larger than any black slick-heads biologists had seen before, and from a depth at which no one knew they lived. Even better, two octopus caught on the survey were only the second and third of the species to have been found in New Zealand waters. Its identity (probably Cirrothauma) is currently being confirmed by cephalopod expert Steve O’Shea, and this find could resolve the status of this particular and problematic taxon.

Meanwhile, Nouvian has returned to Paris, exhibiting our fish in that city’s Natural History Museum. The point of it all is to shine the spotlight on the weird glory of creatures we share the world with but rarely get to see, in an effort to secure their protection. The deep is an ecosystem that has, in the past, been protected by its remoteness. Now that it is so much more accessible to commercial fishing, it is more vulnerable than it has ever been. Paraphrasing from the movie Alien, in the deep sea, no one can hear you scream. Adds Nouvian: “There aren’t any witness.”