The Clifftop world of the three kings

Protected by remoteness, violent seas, steep cliffs and Government decree, the Three Kings Islands north of New Zealand are home to many plant and animal species found nowhere else, and are among our least-known islands. West Island and some of the Princes Islands, viewed from the helicopter’s precarious perch on South West Island, have seen landings from only a handful of Pakeha.

I am sitting very still, writing quietly in the shade of kanuka trees. The trees are old and huge, twisted by a thousand gales into a menagerie of bizarre shapes. About me the ground is littered with decaying branches and twigs. Here and there, tufts of coarse native grasses poke through pockets of rotting leaves. In the distance, blackbirds and bellbirds trill and chortle, while annoying black blowflies drone heavily around me, sucking at my sweaty skin.

Between the buzzing and the birdsong, I start to notice other sounds. From all sides arises a stealthy rustling, and the odd blade of grass twitches. It is as if the Lilliputians are creeping up on me. Some of the sounds are stronger, like a bird scrabbling among leaves, but there are no birds close by. Beady eyes honed by uncountable eons of reptilian vigilance size me up from a dozen hides. I become aware that one of the creatures has crept to within half a metre of me. Slowly I put down my pad and reach for the camera. The lizard, resplendent in gleaming black and gold leather, is now in clear view. At 250 mm in length and possessed of a waist as plump as a sausage, Oligosoma fallai is one of New Zealand’s largest skinks.

Everywhere on this island it is the same. Pause for a few moments and these local lords come to investigate you. Before rats and mice arrived, perhaps much of New Zealand was like this. Now there are just a handful of islands where the reptiles still rule, and this is one of them: 400-hectare Great Island in the Three Kings group, 58 km north-west of Cape Reinga.

I am accompanying eight Department of Conservation staff on the first official visit to these remote islands since 1991. The Kings were declared a sanctuary in 1930 (the Crown purchased the islands from Maori owners in 1908), and there are not supposed to be unauthorised landings, although fishing boats and diving parties frequently partake of the bounty of the surrounding seas.

Landing on these rocky ramparts has never been trivial. Tasman, their European discoverer, tried to send men ashore to get water from “a small safe bay where fresh water came in abundance from a high mountain.” However, the crews reported that “there was a great surf on the shore, which would make watering there troublesome and dangerous.” Tasman also noted that “Upon the highest mountain of the island they saw 35 persons, who were very tall, and had staves or clubs . . . When they walked they took very large strides.”

Next day, Tasman tried again for water, but the combination of “much surf at the watering place” and more natives of questionable friendliness discouraged him from persisting with the attempt. “It being the day of the Epiphany” (1643), Tasman named the place Three Kings Island (now known as Great Island), and sailed on to Tonga for water.

What is not clear from Tasman’s account is that the “fresh water [coming] in abundance from a high mountain” is a 50-metre-high waterfall, where the only permanent stream on the islands dashes over a cliff to the sea. In fact, there is little but cliffs around not only Great Island but every other island in the group. In places the pounding of the waves has cut a platform in the rock, but it is rarely more than a metre or two wide. Of sand there is not a grain. In one or two spots boulders the size of small cars kneel in a narrow band at the foot of the cliffs, but that is as far as the coast relents.

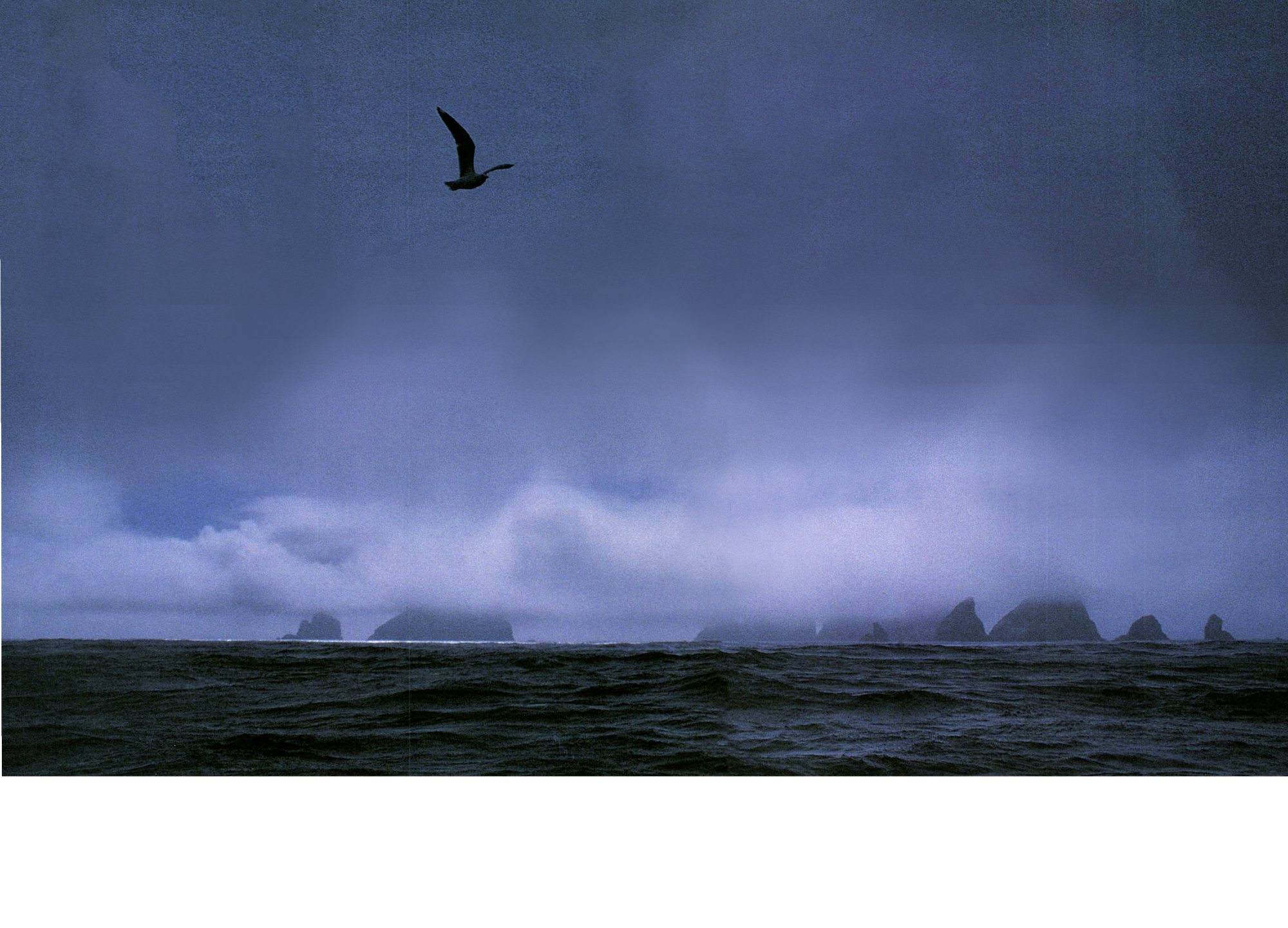

In calm conditions a landing is possible, but around the Three Kings an interminable swell multiplies the hazards. An early visitor noted a swell of “seven to fourteen feet” throughout his stay. I’ve heard it said that you can land safely about one day a month on South West Island; less frequently on some of the others.

On a scientific expedition in 1983, entomologist Charles Watt was perched on a rocky ledge at North East Island, waiting for the swell to lift an inflatable boat high enough for him to leap into. Suddenly a huge wave engulfed him to neck level and sucked him out to sea. Someone in the boat succeeded in grabbing his pack and dragging it aboard, and Charlie proved to be still attached to its underside.

During the same trip there were difficulties on West Island, too. Bruce Hayward, a geologist with the expedition, told me about it. “On a particularly calm day, four biologists were landed on West Island, and it was arranged to retrieve them a few hours later. Another geologist and I were dropped off on cliffs elsewhere on the island, while several divers went down just out from us. We could only move a few metres above the waves, since the cliffs were very steep, and after a time we noticed that the swell was increasing considerably, although the weather hadn’t changed. It happened within a space of no more than ten minutes.

“We were able to signal the boat, and they got us off and hauled in the divers, but around the other side of the island the shore party was high up and didn’t return until the appointed time. By then the swell had increased further, and there was no way that we could recover them. We managed to throw them a small pack with some additional supplies, but they were stuck there for three days before the boat could retrieve them. No tents, sleeping bags, very little food and water, scarcely any ground flat enough to lie on.” Among the items in the pack were a couple of Minties—along with an appropriate note.

I was not at all sorry that our expedition was travelling by helicopter—a big twin-motor job since the trip involved covering a fair stretch of sea—but not even the chopper proved completely invincible. Strong winds forced the postponement of our first flight. Twenty knot winds at the Cape generally mean forty knots at the Kings—unsafe for any craft. Three days later we were back, and this time the outlook was more settled.

For more than three decades I’ve been more strongly attracted to the tail of the fish (as Maori are wont to call the northernmost tip of Aotearoa) than to any other part of Maui’s catch. Yet every time I stand at Cape Reinga, gazing out to the north across empty ocean, I feel a twinge of unease. It is something to do with all of New Zealand being behind me; with having reached the end of the land. Well, the end apart from the Three Kings—insubstantial smudges of blue revealing themselves from time to time along the skyline.

How did I feel about abandoning terra cognita for these ephemeral punctuation marks? Keen to be going somewhere new, of course … but still ambivalent.

[chapter break]

South west island looks like a camel’s hump protruding from the sea as we hover over it searching for a landing site. Touching down is a matter of settling the front of the skids to steady the machine while we scramble out. At least there is no chance of becoming fatally entangled in the helicopter’s rear rotor: the posterior two-thirds of the machine is hanging over a precipice.

Once out of the centimetre-thick orange survival suits—designed to preserve life should you find yourself in the sea, but heavy enough to result in visceral meltdown elsewhere—the scientists are off.

But the going isn’t easy. No cattle, pigs, possums or track cutters have forged paths through this tangle. There are no big trees, just flax, shrubs and scrub. After a few hundred metres of clawing and wriggling through the hostile vegetation, I emerge beneath a grove of enormous puka trees. The trunks are 60 cm through, and the trees stand 10 metres high. Leathery leaves the size of paddle blades rattle in the breeze. I have never seen a forest like it.

Beneath the puka there is mercifully little other vegetation, and I fossick in a pile of boulders and rotting leaves. Giant ants close to a centimetre long scurry about. It isn’t just their size but their heavy-duty jaws that impress me. As a child I read tales of adventurers using ant jaws as stitches. Hold a cut together, entice a few ants to bite, then nip off their bodies. These are the first ants I have seen with jaws suited to that task. Within one cluster is a group of their pupae: bright yellow capsules the size of antibiotic pills.

Under another rock is a creature as curious as any I have ever encountered. With eight spindly legs, it has to be a spider of some sort, but its broad, dark body and intimidating palps covered by studs lend it the menace of a creature sprung from the imagination of Sid Vicious.

Later, I discover that it belongs to the harvestman group of spiders and is closely allied to Triregia monstrosa, described from Great Island and placed in a new genus named for the islands.

Botanist Peter de Lange crashes through the undergrowth to join me. Nearby are some pepper shrubs (Macropiper) with large glossy leaves. He tells me that several species are found on the Three Kings, and collects a branch from a specimen representing an undescribed species.

We push along to the northernmost crag of the ridge, gazing down on seabirds wheeling above the crashing swells. Many are nesting among vivid green grass well down the face. “That’s Cook’s scurvy grass,” Peter tells me. “It seems to be only found in the vicinity of bird colonies. We are starting to appreciate that seabirds have important effects on the ecosystems of the islands they occur on. Their droppings provide nutrients essential for the establishment and survival of whole plant communities, and Cook’s scurvy grass seems to be one of these plants. Depending on the species of seabird and its diet, you get differences in the plant groups in the vicinity.”

Struggling back to meet the helicopter, I become aware of a prickling sensation in my right shoulder. A clump of centimetre-long fine yellow spines has pierced my shirt. “Better get those out,” someone says. “They will work their way in and become pretty painful.” Carefully, I remove them—quills of the native cucumber Sicyos, an endangered plant on the mainland but a common creeper here.

The flight across to Great Island takes only minutes, and the machine comes to roost on a solid wooden platform high on the island. A lighthouse once operated nearby, and the helicopter platform was constructed to service it. Several years ago the light was decommissioned, and scientists now use the base of its five-metre concrete tower as a pantry. Tents are erected on a narrow fretwork of open ground close to the landing pad, but flat space is in short supply, and my meagre tent ends up on sloping ground jammed between shrubs. This is no site for sleep walkers. Five injudicious steps from any tent and you’re over the edge of a 250-metre cliff.

Great Island is shaped like two triangles joined through a narrow neck, the western triangle being at least three times larger than the eastern. I elect to accompany Don McKenzie and Trevor Bullock to the neck. According to the map it is perhaps 500 metres, but we take not much under an hour, even though it’s all downhill.

The vegetation here is quite different from that on South West Island. Old kanuka forms a canopy five to ten metres high that extends over most of the island. Dead boughs obstruct every step. Through them, between them, grow assorted shrubs, especially the spiky Coprosma rhamnoides, but there are many others.

Don explains that Great Island’s vegetation has been subject to considerable upheaval in the past. “Tasman noted the presence of Maori here in 1643, and the absence of trees, but observed some patches of crops. A hundred and thirty years later, Marion du Fresne reported that Great Island was still inhabited, and covered in grass with copses of bushes. Maori occupation continued until about 1840, and the feeling is that they cleared, and maybe cultivated piecemeal, all the island apart from the cliffs. Then, in 1889, four goats were liberated here to feed possible castaways. They reproduced very successfully, and devastated whatever vegetation remained, particularly the broadleafed plants. When the goats were finally exterminated in 1946, there were 393 shot.”

Thomas Cheeseman, an early curator of the Auckland Museum and a distinguished botanist, noted that ti tree was the main plant when he visited Great Island in 1887 and 1889, but he also recorded many species that have not been seen since—presumably wiped out by the goats. Other species that were not uncommon when he visited (such as karaka) are now very rare. But all is not gloom. The large-leafed puka (111elyta sinclairii) was not seen at all on Great Island until 1946, when a single seedling was spotted on an inaccessible ledge. Now trees two or three metres high are common amid the kanuka, and in some places much larger trees exist. Red-billed gulls (the islands are a major breeding ground) have been seen feeding on the seeds of this tree on South West Island, and could spread seeds, as do exotic birds such as blackbirds.

Don is concerned at the increase in numbers of another bird, the myna. It has been present on the islands for 25 years, and elsewhere in the country is increasing in abundance, often at the expense of native birds. Not only does it compete for virtually every type of food, but may destroy eggs and young of other birds.

The Kings are host to a polyglot assortment of birds. Bellbirds (a distinct Three Kings subspecies) are abundant, and the fast-flying red-crowned parakeet (kakariki) is common. Furtive banded rail and spotless crake slink unseen, but sometimes heard, through the undergrowth. Kingfishers, hawks, morepork, pipit, and fantail constitute the rest of the native land birds, but quail, chaffinches, blackbirds, starlings, thrushes and sparrows are all present. Don hopes that if there are not too many mynas it may be possible to shoot them out.

While we await dusk and the possible arrival of mynas to roosts on the northern cliffs, we find an old rope that dangles down the precipice. Once used to ease access on to the island, it is now pretty rotten. Near the top of it are remains of an old bag of fertiliser. To me it is an incomprehensible find, but the others know better. “Marijuana growers’ stuff for sure,” says Trevor. “Plants were found on Motuopao Island off Cape Maria Van Diemen the year after DoC cleared the island of rats. Probably fishermen trying to make an extra buck.”

The myna report is bad. As daylight fades, hundreds of mynas—far too many to shoot—are flying in to the relatively small area of cliff face we can view, and there are certain to be other roosts.

[chapter break]

The three kings are special not just because mammalian predators and possums are absent. They have been isolated from the rest of New Zealand for 20 million years, Fred Brook tells me, “and that has been a sufficiently long isolation for many distinct species to have evolved on the islands.”

During some of the ice ages (the most recent only 20,000 years ago), sea levels were 120 metres lower than they are at present, and all the Kings would have formed a single landmass, probably over 100 square kilometres in area. The channel separating this land from Cape Reinga could have been as narrow as 10 kilometres then. As a result, endemism among birds (and the plants whose seeds they carry) is relatively low, but among organisms not capable of crossing the water barrier it is high. For instance, almost all of the 30 species of land snail found on the Kings occur nowhere else. And some plants are restricted to the islands—even to just one or two of the islands. Elingamita johnsonii—named for the ship that was wrecked just below the spot where the first specimen of the plant was discovered (see sidebar page 41)—is now found only on West Island and one of the Princes. The large glossy-leafed vine Tecomanthe speciosa occurs as a small cluster of plants all derived from a single parent by natural layering in Tasman Valley on Great Island (although it has been propagated by cuttings and is widely available from garden centres).

According to that infallible reference work, The Guinness Book of World Records, the rarest tree in the world is another Great Island endemic known from only a single specimen in the wild that was discovered in the late 1940s. Peter de Lange takes me in search of the sole naturally occurring example of Pennantia baylisiana, and we spend an hour combing the less precipitous upper reaches of a north-western cliff, me rather vague about what I’m seeking. When Otago botanist Geoff Baylis discovered the tree in the late ’40s, the ground about was bare. Now that the area is wooded, the tree is much harder to find.

At length the sacred specimen is uncovered, but I’m disappointed—it doesn’t look special. It has smaller leaves than a puka, and is perhaps five metres high. Clumps of 2 mm green berries deck the tree, and about one in a thousand is 4 mm. These larger berries are possibly fertile seeds. “Fruit was observed on this plant for the first time in the late 1980s,” Peter tells me. Based on material he took back to Auckland, Peter was to find that fewer than one fruit in 2000 was fertile.

The tree has not been seen for three years, and Peter is concerned by its deteriorating condition. Cuttings have been taken previously, and several hundred clones exist back on the mainland in various gardens. Peter considers that the species is very closely related to a Norfolk Island Pennantia, as are a few other Three Kings plants, such as Cordyline kaspar, the broadleafed Three Kings cabbage tree. It is unlikely that land ever connected the Kings and Norfolk Island directly, but it is thought that at some time a series of islands rose and fell to the north of New Zealand, providing a series of stepping stones perhaps as far north as Melanesia.

As I thread my way back through the bush, a morepork springs from the ground beside me and alights with fierce glare on a dead branch mere metres away. Morepork are never visible by day on the mainland, but here I see several. We even find a morepork “nest.” The absence of predators on the islands means at least some morepork nest on the ground. The nest is merely a cavity beneath a large rock containing an unhatched egg and a very small white chick so young it can barely stand. On the floor of the hollow are half a dozen dead geckos, but the chick doesn’t look to be able to tackle such a meal for a while yet.

Not a hundred yards beyond where I encounter the morepork, I’m startled by something small and brown leaping from the ground at my very feet and racing away through the undergrowth so fast I can’t get a good look. Back home it might have been a young rabbit, or possible a large rat, but what could it be here? The accidental introduction of rats and mice from an illegally visiting boat is a constant worry for the Department of Conservation. The islands are too remote to police for landings, although their inhospitable shoreline affords a measure of protection. Don, Trevor and David Neho have checked permanently established bait stations by Castaway Stream, and have also set up a variety of other traps since we arrived. To everyone’s relief, all they have caught is the big skinks. When I tell them about my encounter with the fast-moving brown object, they decide I’ve seen a brown or Australian quail.

Cheeseman first saw quail on the Kings in 1888, and identified them as the now extinct New Zealand quail, but Walter Buller soon recognised that the eggs Cheeseman had collected belonged to the introduced Australian species. How it got to the Three Kings remains a mystery.

Land snail expert Fred Brook, at his own request, is spending the four days of the expedition in solitary exile on North East Island, an outpost that has been little explored. The helicopter deposited him there after dropping the rest of us on Great Island. Each evening at eight he checks in by radio for a few heartwarming moments of human contact that go something like this.

Don: “This is DoC 5 calling DoC 7; come in Fred.”

Fred: “This is DoC 7 calling DoC 5; I’m here Don.

I’ve spent the day grovelling amongst pockets of trees but haven’t found anything. Talk to you tomorrow. DoC 7 over and out.” All this with the same tenderness with which MetService announces rain in Westland on National Radio.

Similar conversations happen with DoC at Te Paid, our only contact with the world beyond the cliffs. At times we can glimpse the ephemeral pale sands of Te Werahi Beach and the huge sand tombolo which anchors Cape Maria’s rocks to the rest of New Zealand, but that’s all. Is there a world out there? Have the French let off another bombe? Who cares? Some days our world extends barely 20 metres. Thick fog cocoons the islands for much of the time, despite a stiff breeze.

I have trouble deciding whether the islands are wet or dry. Kanuka has a parched, dry look, but mosses, lichens, and liverworts dangle from many of the branches. Underboot, the ground is not wet, but in many places ferns of the more robust type form a carpet and creep up trunks. There is only one permanent stream, but other valleys contain creeks for much of the year. Perhaps fog holds the key to the water balance of the place, providing the moisture denied by the lack of rain. I ponder these deep matters as I wade through the undergrowth in the company of Joan Maingay, a DoC archaeologist in search of vestiges of pre-European occupation.

A representative of the last Maori known to have lived on the islands—Tom Bowline—told the Maori Land Court over a century ago that the islands were once inhabited by about 100 people under the leadership of one Tournaramara. In the late eighteenth century a party of Aupouri Maori led by Taiakiaki killed most or all of these people. Although Taiakiaki did not remain on the islands, one of his sons, Tongahake, made repeated visits and was buried on Great Island. Tom Bowline married Tongahake’s daughter and lived with his children on Great Island through the 1830s until about 1840, when starvation forced them to return to the mainland.

The 35 inhabitants spotted by Tasman would have been well over a century earlier than Toumaramara’s era, so the islands have clearly been inhabited over a lengthy period. Some Aupouri claim that the original owner of the Three Kings was a chief named Ranui. He swam across to the islands from the mainland and, exhausted by the effort—as well he might be—named them “Manawatawhi,” meaning panting breath. Saana Murray, a kuia from the far northern Ngati Kuri, told me that her people periodically used the islands as a place of refuge from strife on the mainland. “They also went over to the islands to catch hapuka and harvest seabirds and eggs.” On the morning of our departure for the islands, kaumatua Ross Norman and Graham Neho had launched our expedition with karakia.

Undergrowth now shrouds the contours of the land, making detection of archaeological features difficult. One W M. Fraser of Whangarei, who spent three days on Great Island in 1929, was the first to mention signs of former Maori occupation. Thanks to the appetites of the goats, they were much more obvious then. He estimated from the extent of terracing and piles of stones that cultivation in Tasman Valley—the very place we are now in—covered 30 hectares. I can see piles of stones, and certainly the ground is flatter in some places than in others, but to my inexperienced eye it looks as though nature arranged things thus.

In the course of several days, Joan has identified three new archaeological sites with mounds and terraces in the valley, supplementing those previously noted by geologist Bruce Hayward, who found a dozen sites scattered over Great Island, and one each on North East Island, South West Island and West Island. The main features were terraces and retaining walls, but he also identified a cluster of five whare sites in Castaway Valley on Great Island (named for the provision depot that was established there in 1907). Notable for Hayward was the absence of food storage pits—used throughout the mainland in winter to keep yam and kumara warmer than 10°C, to prevent tissue damage. He speculated that the climate on the Kings must be warm enough for vegetables not to require this sort of protection.

Near the mouth of Tasman Stream it is airless and stifling. Pohutukawa, with brighter, lighter blooms than most of those I see around Auckland, contrast with the vivid green of the puka above dark pools of water. Chattering kakariki, darting in their purposeful way through the trees, are especially common down here. Renga lilies bloom along the banks amid, unexpectedly, familiar weeds. How did they get here?

According to Peter de Lange, the range of weed species found on the Kings keeps increasing. “Some seeds may come with people—the weediest area on this and other islands is usually around helicopter landing pads—but we don’t think that that is the complete explanation. We wonder whether some seabirds ingest weed seeds floating in the sea, and ferry them ashore.”

I’ve noticed several different grasses, including paspalum and kikuyu, and there is dandelion and Scotch thistle, too.

Just beyond a patch of the dreaded Sicyos Tasman Stream falls into the sea. It seems an inappropriate, violent end: one moment its waters pleasantly murmuring down rock ledges, loitering in slow pools, then helplessly trickling over a ledge that is more than 50 metres high to spray on to the surf or just be disdainfully frayed to nothing by the wind. Not the easiest place to fill a water barrel.

My sleep that night seemed pierced by strange cries, but in the fog of morning I decided that I’d imagined them. Then Joan asked if I’d heard the birds in the night. “Various sorts of petrels nest in burrows around the island, and they return from the sea during the night uttering their peculiar cries,” Don explained. Don had had a surprise in the night, too. Rummaging through his pack at 4.30 A.M. (why he should be doing this was unclear, but I heard that he was so accustomed to being woken by a baby at home that he was having trouble sleeping), he had come upon a giant centipede sliding swiftly through his gear. He had caught it, somehow avoiding the disagreeable fangs and tail barbs.

I was pretty impressed with the DoC people. They were fit, tough, knowledgable, dedicated, fearless. They would describe climbing vertical pinnacles on remote islands, then falling off into the sea below, with more nonchalance than most people would describe driving to the office. They adored wetas and big spiders. But all drew the line at giant centipedes. Several related tales of acquaintances who had suffered weeks of swelling and agony following a bite.

By day, centipedes are to be found under rocks and in leaf litter, but at night they emerge to hunt, scaling trees and roaming through packs. An entomology expedition to Great Island in 1970 was so bothered by night visits from centipedes that they spread tinfoil bread wrappers around each sleeping bag. Feet rattling on the foil alerted nervous sleepers to the arrival of the unwelcome visitors.

Certainly, they are pretty fearsome: 250 mm long, a shiny segmented body close to two centimetres wide, and pale blue legs beyond that, a streamlined but formidable pair of fangs fitted along the side of the head and, tucked under the rear, a couple of thorny spines like miniature stingray barbs. An abundance of legs means these creatures can insinuate themselves into any crevice with the fluidity of mercury.

The menace of a snake, scaliness and legs of a pot of cockroaches and jaws of a tarantula don’t add up to a very appealing package. But they are even worse than the sum of their liabilities. All those repeating segments—as if machine made and assembled—together with the absence of visible eyes impart a uniquely menacing and alien air.

Auckland Museum was anxious for us to capture a few specimens, as there is a suspicion that the Three Kings’ centipedes could be a different species from those on the mainland. Putting two individuals together in a large plastic bin produced vigorous combat, although there were no immediate injuries.

[chapter break]

Scientifically speaking, things are going well for the expedition. Richard Parrish has discovered a number of specimens of a distinctively hairy small snail, previously known from a single pile of rocks covering only a couple of square metres. Peter de Lange has lugged a hefty stainless corer down to a parcel of swampy ground where the two main branches of Tasman Stream intersect, and has managed to take a core of sediment which, when analysed for pollen and sediment particles, should provide a wealth of information about the islands’ flora and geological history over the last 1000 years. He and Trevor have also found, for the first time, a Maori pa site on the islands, atop the high north-west corner of Great Island above Hapuka Point. Facing north-west, poised to protect against invading hordes from . .. Norfolk?

Fred, in the course of his grovelling on North East Island, has uncovered several specimens of a new species of snail and lots of Maori rock work. Ray Pierce has criss-crossed much of the island in the course of completing a bird census, and is finding that Great Island is a major holdout for many seabird species.

I de