The canine conundrum

Man’s best friend has been part of the human scene for the last 10,000 years.Even so, we still exhibit a love/hate relationship with our four-legged companions.

If there were a competition in New Zealand for the animal that causes more problems, fires more emotion and starts more fights than any other, the dog would win hands down. The rabbit or the possum wouldn’t even come near it.

To justify this outburst, let me declare my hand at the outset. I, like many other members of Homo sapiens, have a love/hate relationship with dogs. I can adore one breed and despise another. A faithful dog draws out my deepest affection; the miserable cur that has just fouled my lawn is likely to be on the receiving end of a well-thrown lump of four by two.

I am not alone in displaying such ambivalence; I believe it is the basic reason why we are witnessing a rising tide of concern about dogs and dog behaviour.

Dogs have a long history in New Zealand—a thousand years or more. The first of them were brought to Aotearoa by Polynesian voyagers, and were used for hunting and for food. The Maori kuri were low-set with erect ears, and either white, black or black-and-white. They were popular eating, and when Captain Cook was offered some in Queen Charlotte Sound in 1770 he declared it indistinguishable from prime mutton.

By the early 1800s the breed had been lost through crossing with the big rangy dogs introduced by European whalers. The resulting feral population did great damage to the native wildlife—flightless birds, in particular, finding themselves to be literally sitting ducks.

Nineteenth century wild dogs soon developed a taste for sheep meat, and the hunter quickly became the hunted. Angry settlers declared war on them, bringing in hounds for seek-and-destroy missions. What the farmers didn’t kill, poisoned rabbits did, and there is little evidence that these early wild dogs survived long enough to make a genetic contribution to the working dogs for which New Zealand is now justly famed.

The forerunners of today’s Flo, Tip, Jet and Wagg were Border collies from the hill country which separates England from Scotland. Without them, New Zealand could not have become a meat and wool exporter, and our agricultural history would have been a totally different story.

A farmer’s dogs are still his main farm help, whether roaming the high country mustering merinos or bringing in the cows morning and night for milking. On difficult country, they can do in a day what would take a man a week, and we are so proud of them that we even sit down and watch them compete on TV.

It is not farm dogs that have been hitting the headlines and giving Canis familiaris a bad name. The mutts in the back of the dog ranger’s van are city born and raised, and there are just too many of them.

More than a quarter of all New Zealand households own one or more dogs. According to council registration figures, which include all types of dogs, in 1991 we had 512,434 dogs (working and non-working) belonging to 343,443 owners. Nobody knows how many unregistered dogs (including puppies) there are, but a safe guess would be well over 100,000. There is a rising tide of opinion in this country that says we could well do without a large proportion of these animals

Unfortunately, getting rid of surplus dogs raises as many problems as keeping them. It costs money, and more often than not it ends up being “someone else’s problem.” That someone usually turns out to be the RSPCA.

“Our people and the dog control people in each area are sick to the back teeth of having to put dogs down—dogs which would in many cases have made wonderful pets and companions,” says National Coordinator for the RSPCA, James Boyd. Each year, throughout New Zealand, between 20,000 and 30,000 animals are destroyed, Boyd estimates. “And the only way to prevent the deaths is by preventing the births. That means ensuring that every dog which is not specifically needed for breeding is speyed or neutered.”

So far, getting that particular message across to the dog-owning public has been about as successful as teaching the animals themselves not to bark.

Remarkable as it may seem, when you compare a tiny Chihuahua with a Great Dane, all dogs belong to the same species, and are theoretically capable of interbreeding and producing fertile young. Dogs can even interbreed with wolves. Along with their other cousins, the jackals, foxes and hyenas, domestic dogs derive from an ancestral wolflike canid known to palaeontologists as Tomarctus, which lived 20,000 years ago. The key to understanding dogs, say animal behaviourists, is to study wolves. The interactions of these animals in the wild provide a basis for interpreting domestic dog behaviour.

Imagine yourself as a wolf. You live in an extended family made up of separate hierarchies of both sexes, each with a clear social order. The top dog is the alpha male. He does all the mating and will fight to the death, if need be, to hold this position. Then comes the beta animal, and so on down the pecking order within each sex. Immature, young or sick animals are at the bottom of the heap. The ranking is in a continual state of flux, with individuals challenging and being challenged for position. Threats, skirmishes and, as a last resort, out-and-out fighting are the means by which disputes are settled.

It isn’t hard to visualise the odd stray wolf cub being picked up by a club-wielding hominid or his children and taken home to liven up the Cro-Magnon fireside. The cub soon recognises a human hierarchy operating, and finds itself fitting neatly into the family structure.

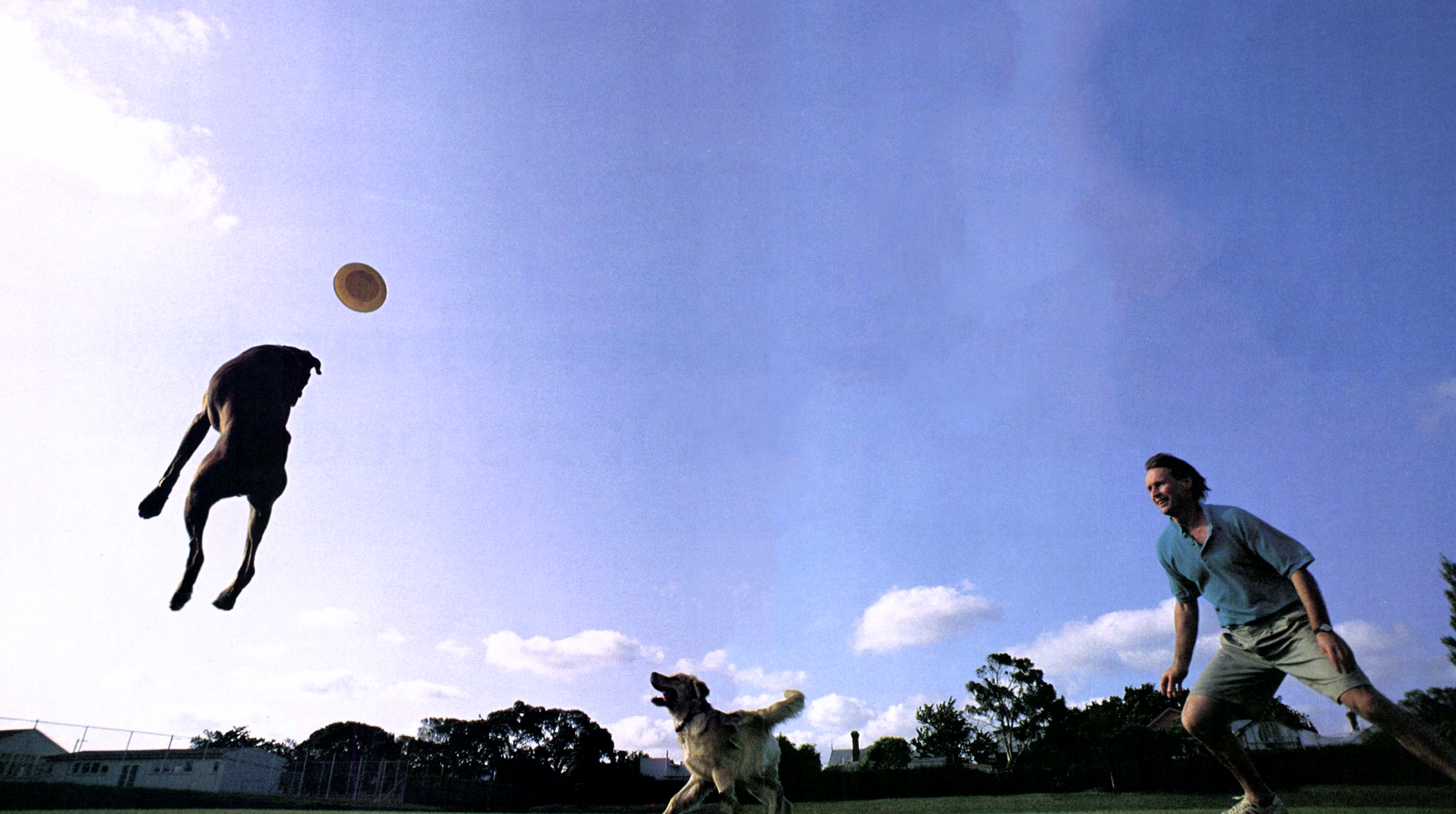

In no time at all, man’s best friend has become part of our lives, providing a whole range of services from hunter to hot-water bottle. Today’s New Zealand dog might retrieve fowl for a duckshooter or fetch newspapers for a pensioner. It might locate fungi in a field for a truffle-farmer or drugs in a suitcase for an airport security officer. It might run around a track for punters or ride a skateboard for advertisers. It might help the disabled, guide the blind, find the lost, round up the flock, disarm the criminal, protect the premises or entertain the crowds.

In other cultures the list could be extended to include disposal of food wastes, provision of pulling power, participation in religious rituals and even ending up on the plate as dinner. In Australian Aborigine society, dogs still play an important role as providers of warmth. The coldness of a night is described in terms of dogs. A one-, two- or maybe more-dog night describes the number of dogs you need to keep warm—the equivalent of the control stops on an electric blanket!

So, who gets the best deal in this friendship, man or dog? The ancestral dog sacrifices some of its natural freedom in exchange for a few compliments and the odd mammoth bone thrown its way. Man accepts the services the dog provides, and offers the dog certain basic rights in return. Of course, the dog cannot negotiate its side of the domestication contract, and relies on his master’s good nature. Not surprisingly, this is the part of the contract which is most often ignored or broken, and so-called dog problems—which usually turn out to be dog owner problems—are the result.

To see where this long dog-man association has led to, start with the nearest dog show. Here you’ll find excitement, tension, tears and triumph, all mixed together in one great spectacle. Smells, often more of the boudoir than the kennel, suffuse the area. Competitors—some in a hyperactive spasm of fussing and titivating, some in depressive anxiety—wait for their turn. Grim-faced judges with awful decisions to make watch and are watched.

The most striking impression, though, is the sheer variety. You crouch down to admire a pocket-sized papillon, then turn around to find yourself nose-to-muzzle with a giant schnauzer. The dachshund has a snout so fine you could use it as a fountain pen; the boxer has no snout at all. It’s hard to believe that all this diversity is the result of one factor: selective breeding, orchestrated by human beings and initiated long before Mendel thought of his peas and Darwin his finches.

Many of the breeds shown so proudly today at dog shows started their existence as genetic freaks which somehow escaped euthanasia. Some breeds, like the Pekingese, have gross malformations of the lower jaw, which give them constant trouble with their teeth and their eating ability. Other flat-faced dogs have breathing difficulties, and for short-legged, long-bodied dogs slipped discs can be a problem. Bulldogs, which were bred for bull baiting in the 17th century, can have difficulty giving birth, and often need Caesarean sections. There must be well over 50 recognised genetic defects in today’s breeds which would have gone against “the survival of the fittest” in nature. Should humankind be complimented or criticised for this endeavour?

Where breeding has favoured increased strength and aggression, criticism has been sure to follow. Top of the hate list at the moment is probably the American pit bull terrier. The New Zealand Kennel Club, like its counterpart in Britain, will not register the pit bull as a breed, though that hasn’t stopped enthusiasts bringing them into the country (there are an estimated 1000 to 1500 here).

The problem in dealing with such breeds is one of balancing the rights of the legitimate breeder or owner against the public interest. When powerful dogs are encouraged to become aggressive or are kept only for their macho image, they tend to give their whole breed a bad name, and the situation becomes even more difficult to resolve.

Public hatred for certain breeds is often media-led, according to Auckland’s Dog Control Manager, Paul Stephenson. “People phone us and tell us they’re being challenged by a Rottie or a pit bull terrier, but when we get there we find that it’s a Jack Russell terrier or a Lab. Many people don’t know one breed from another, but if the media say bad dogs are Rotties or pit bulls, then that’s what the dog must be.”

When dog control officers are brought in to sort out canine trouble, they try to find out why the animal did what it did, and then ask whether it was normal or abnormal dog behaviour for the particular situation or environment the dog was in at the time. That means trying to see things from the dog’s point of view—something every dog owner should do.

Much can be learned about dog behaviour by watching the growth of a pup. For example, a newborn pup’s natural instinct is to burrow into warm surfaces, looking for the teat. This “contact comfort” is such a strong impulse that it remains very important to the dog for the rest of its days.

In the first 12 to 16 weeks, a pup learns almost all its social behaviour. In this time it should be introduced to everything that it will meet later in its life with you—other dogs, cars, grown-ups, children, babies, other pets, posties, meter readers, loud noises, water—everything you can think of!

After this age—about the time when a wolf cub would be emerging into the outside world—it goes into a period where it sensibly learns to fear potential threats.

The main point to remember during rearing is that a dog is a pack animal, and most pack animals are keen to fit into a clearly defined hierarchy, either with other dogs or with a mixture of dogs and people. The dog then knows where it stands. Trouble arises when the animal is confused. Is that any different from humans?

Another interesting feature of early rearing is that once the bitch discourages the pups from nursing, the pup’s focus of interest shifts from the mother’s teats to her muzzle. Pups lick the muzzle while assuming the crouching body position of a low-ranking pack member.

In wolves and other wild dogs, this muzzle contact induces regurgitation of partially digested food by the adult. Fortunately, this method of feeding is not a feature of the domesticated dog, but modifications of the behaviour remain. Dogs that know each other meet nose-to-nose, and who is to say that when your pet greets you by enthusiastic face-licking after work, it’s not asking for some of your regurgitated lunch?

The method of greeting among unfamiliar dogs is nose-to-anus. A dog’s anal glands carry distinctive personal odours which characterise the animal. The anus has been described as the place where a dog keeps its complete curriculum vitae; a sniffing stranger is merely accessing this biographical information. Conversely, by putting its tail between its legs, a frightened dog is hiding its identity.

To be a successful dog owner you have to establish dominance—to be the pack leader. So many dog problems arise because the owner (or family members) is not seen as pack leader, or as dominant animals, and the dog regards itself as being higher up the social hierarchy. Dominance has to be settled once and for all in the first four months. Otherwise, the dog will challenge you, probably when you least expect it, and it will challenge strangers who have to handle it—particularly people who may have to stick needles into it, like veterinarians.

Aucklander Mark Vette is an animal behaviourist. His business is to sort out animal behaviour which has become tiresome for the owners—or for posties or newspaper deliverers. He runs courses to teach people how to minimise the hassling they get from dogs.

Recently, he had a client whose dog had almost forced her out of her home, because it had become the dominant member of the household.

“Slowly, this woman’s corgi forced her out of her territory around the house. First it was the couch. She sat on the couch; the dog bit her. Then it was the bed. She would get into bed, the dog would arrive and bite her for being there.”

Chased out of her own boudoir, the owner tried to create a second dog-free bedroom, but the corgi challenged her right to be in that room, too. In despair, the owner started taking the dog to Vette’s sessions, where both were straightened out.

What had happened here, Vette explains, was that since the owner had been unassertive, the dog had gradually established sites around the house which it claimed as its territory. “Soon, when the owner wanted to use them, the dog started telling her, through biting, ‘This is my patch. You’re not allowed here.'”

A sure way to assert and retain dominance, says Vette, is to make sure the dog knows who controls the resources: the food, the pats, the rides in the car. He has a technique which he calls “nothing in life is free.”

“Make the dog work for what it wants,” he says. “Before it gets its food, goes out the door, gets in the car, make it do something to earn it. That way, you make it use soliciting behaviour, and when a dog solicits, it means that it is recognising you as the boss.” A couple of months of this regime, says Vette, and you’ll never have another dominance problem.

Here is a summary of how to establish good human-dog relations for the rest of the dog’s life. Remember, this could be for the next 10 -13 years, so it’s worth the effort.

- Feed the pup yourself, so that it associates you with control of its food.

- Occasionally interrupt its feeding for a few seconds. Praise the pup and return its food.

- Never deliberately call the dog to you to administer discipline.

- Get the pup used to being separated from you for longer and longer

- periods during its first four months.

- Never change the rules—be consistent and praise it regularly. If it shows dominance or bad habits, shake it vigorously, then praise it when it shows submission.

- Make sure nobody else in the family is teaching it another set of rules.

Appreciating how a dog perceives life is an important way of avoiding trouble, especially when you are meeting a strange dog. Touch is very important to a dog. Indeed, to touch a dog is to pay it the highest compliment—provided it is in the correct, non-threatening way. Mark Vette warns: “Don’t handle strange dogs around the head, upper neck and shoulders—that’s where most people pat dogs, but to a dog, that’s the threat area. Hold your hand out and let the dog sniff you, then rub its chest or under its chin.”

Getting the dog’s perspective means understanding its other senses as well. In general, a dog’s vision covers an area which is up to 70 degrees wider than a human’s, but its binocular (two-eyed) vision, which provides accurate perception of distance, is about 20 degrees narrower. As a result, dogs can pick up movement about 10 times more readily than we can, but they don’t have our ability to see things close up and in detail. A dog’s eyes are adapted to low light, so they have better night vision than we do, but they have only limited colour vision.

At close quarters, a dog relies more on its nose than its eyes. This is no hardship, as the canine sense of smell is, with some scents, a million times more sensitive than a human’s. While the human nose has around five million olfactory (smell) cells, dog noses have 220 million.

Dogs outstrip us in hearing, too. Their ears detect a much wider frequency range than ours. Human hearing peaks at 20,000 cycles/second, but dogs can hear sounds at frequencies of up to 50,000 cycles/second. To us, the high-pitched “silent” type of dog whistle merely makes a hiss. To canine ears, such whistles probably have all the beauty of a soprano’s high C.

Vocalisation and posture are the two means a dog has to make itself understood. In common with most mammals, dogs use growls for aggression and whimpers for fear or submission. But what of the dog’s trademark—its bark? No one seems to know. Perhaps it’s their way of reminding us—usually when we’re trying to sleep—about the domestication contract.

Based on these observations, Vette has advice for women owners, particularly. “When talking to your dog, the sound and tone of voice is important. Deep tones equal a growl: authority high tones mean that someone is begging. And that’s something women, with higher voices, should be aware of.”

[Chapter Break]

Dogs are on the increase. Although the national increase was only one per cent last year, in some places, like Cambridge and Te Awamutu, dog numbers boomed by as much as 25 per cent. It is when dogs form packs, though, that there is trouble. Most pack behaviour results from dogs pursuing females which are in season. If a bitch is allowed out on to the streets, dogs will come from as far away as a kilometre, and that can mean whole crowds of dogs suddenly descending on an area. Determined dogs can cause major problems for the public—and they can be very hard to catch.

“Last year we chased one pack of about 15 dogs for over a week,” says Auckland dog control officer, Michelle Manley.

“Day after day, they were charging through streets and through the middle of a shopping centre, knocking over old people and children. They were running across roads, and cars were hitting them and each other. The one we go after is the bitch—once you have her the other dogs lose their focus and you can pick them up one by one. But we couldn’t catch this female. She knew all the shortcuts across properties, every back alley. It took us days to finally catch her.”

Roaming dogs become extraordinarily cunning about avoiding capture.

“They’ll know the houses that are friendly to them, so when we arrive they’ll head for those places and sit on the verandah as though they live there. Or they’ll attach themselves to groups of schoolchildren and trot along behind, pretending they’re with the kids.”

Many local authorities believe that microchip implants should be mandatory, if not for all dogs, then at least for dangerous ones. The chip, about the size of a grain of rice, is injected under the dog’s shoulder skin. There is a number on it which can be read by a scanner should the dog be impounded or injured. Owner details, medical records, even breeding details can all be kept on files held by the local authority or the company which distributes the chips. The technology has been in New Zealand for the last three years, and between one and two thousand dogs now have the implants.

While stray dogs cause problems in public places, protection dogs are becoming a big worry for service people who have to visit private properties. It’s bad enough going to the gate to deliver the mail, but stepping into the dog’s territory can be extremely dicey. Recently in Hamilton an ambulance attendant rushed into a house to attend a child who needed emergency care, and was attacked by the family dog. The attendant became the patient, and had to leave in the ambulance she came in!

The dogs favoured by security-conscious householders are, first of all, big, and second, not the sort that wag their tail and roll over when strangers approach. A survey in Auckland among 3000 newspaper delivery boys and girls showed that in a three-month period, 68 were attacked in the street and 38 at the letterbox. These attacks were more than just dogs rushing at newcomers to express their friendship. They were serious, sometimes savage, and they were probably the result of owners deliberately encouraging their dogs to regard strangers as a threat.

Mark Vette’s advice to people confronted by dogs which mean business is simple: “Stand still, turning side-on to reduce your profile, and avoid eye contact. And although this goes against human behaviour, crouch down. That shows you are submissive. Then depart from the property slowly. You may lose dignity, but you may save yourself from being bitten.”

There are alternatives, such as ultrasound devices designed to give dogs an unpleasant aural shock, but they cost from $50 to $100, and are not always effective. An automatic umbrella can be a useful accessory, and if you are a big person you can risk telling the dog what you think of it in a loud deep voice—but this may only have temporary effectiveness.

And how does the law protect the citizen from dog attack?

Under current legislation, owners of a dog are liable for any damage done by their dog. The injured person does not have to prove “previous mischievous propensity” in the dog, which means that the first time it attacks or injures, the owner is liable.

Section 56 of the Dog Control and Hydatids Act, 1982, states that “any person who sees a dog attacking any person, stock or poultry, or who is himself attacked by any such dog, may forthwith either seize or destroy the dog.” The Act also comes down hard on the owners of dogs which rush at cars or people, and owners of potentially dangerous dogs are bound under the Act to keep their animals muzzled or confined in public places.

The law is not toothless when it comes to dogs, but there is a strong public lobby for even tougher regulations and penalties. The Department of Internal Affairs, which is currently reviewing the Act, recommends in its report that a maximum penalty of one year’s imprisonment or a $5,000 fine or both apply to the owner of a dog which causes serious injury to a person.

In New Zealand, one of the most distressing activities of out-of-control dogs is the harassment and even killing of sheep. Garth Jennens, a New Zealand animal behaviourist who has been researching dog attacks on sheep in Western Australia, recently published his findings, which contained a number of surprising conclusions.

The first point to realise, says Jennens, is that dogs are dogs, and it is pointless for an owner to argue that their little Fifi could not possibly go out and kill. Almost any dog is capable of killing sheep, and the fact that it is sleeping on the doorstep when you wake up in the morning is no proof of innocence. Attacks can happen any time, but 80 per cent occur between 5 a.m. and 7 a.m. You cannot breed this killing instinct out of the species. If you did, they wouldn’t be dogs.

The popular image of killer dogs going around in packs, however, is a myth. Ninety per cent of dogs that kill sheep are pets, working on their own or with another dog, and they come in all sizes and breeds. They can be obedient companions or top working dogs for years, and then, all of a sudden, something triggers off a primordial urge to hunt and kill. “As far as they’re concerned, they regard stock as another food resource,” says Paul Stephenson.

One common factor in all sheep killers, though, is that they are wanderers. Killer dogs are predictable and have a set pattern. They enter and leave properties by a set route, and have usually been around the area they kill in for a few visits before they get to work. They like to travel near water or up valleys where scent is funnelled down to them. And they are particularly dangerous when working in tandem with another dog.

“About three years ago there was a long-running sheep-worrying case, where two distinct parts of the animals, the back feet and the throat, were being attacked,” says Stephenson. The worriers turned out to be a terrier cross and a dobermann. “The terrier would grab the sheep by the heels and slow it down, while the dobermann would go for the throat.”

To get a feel for the impact of our growing dog population, consider the amount of faeces produced each day. At about 500g per dog per day, a place like Manukau City, with 21,000 dogs, is blessed with ten tonnes of dog manure each day. What went in to the city’s dogs would be a slightly larger amount of food—which makes it easy to see why our television screens are ablaze with dog food commercials.

Feeding New Zealand’s cats and dogs has become a multi-million dollar business with a huge proliferation of pet foods in supermarkets, and the opening of specialist pet care shops. Of the $191 million which New Zealanders spent on all animal food this year, $76 million of that was for dog food—canned, dried and in rolls.

When considering the merits of particular types of food product, it is worth remembering the dog’s wild canid ancestors. They found it best to eat quickly (wolfing down their food, if you will!) and meals were either a feast or a famine. Also, they ate virtually anything—their diet varying from freshly-killed meat to rotten, stinking carrion. They preferred variety.

Palatability trials, where dogs have been given a free choice of food and their preferences measured, have produced some interesting surprises. Researchers found that dogs prefer pork and beef to mutton. Cooked meat is preferred to raw meat; ground meat to chunks. Dogs also prefer their food warm, wet and sweet. Remember, this says nothing about nutritional value—just what a dog prefers if given the choice.

Qualities such as rich colour, juiciness and chunkiness, so regularly stressed in petfood advertisements, by and large have nothing to do with the dog’s preferences, but what the owners perceive their animals want.

Haute cuisine hardly seems relevant when dogs regularly eat their own vomit, and occasionally their faeces—one of nature’s ways to ensure they get all the minor trace elements and vitamins they need.

Some owners have the mistaken belief that since dogs are carnivores they will thrive on an all-meat diet. This is not so, and an all-meat diet requires substantial supplementation with minerals like calcium, phosphorus and iodine, as well as vitamins.

At the other end of the spectrum, many dogs suffer from poor nutrition because their owners cannot afford meat, and try to get by by feeding their dog a pig’s diet of household scraps. Disease and uncontrollable behaviour are the inevitable result.

“Kitchen scraps should only make up 15 per cent of a dog’s diet,” says Hamilton veterinarian Dave Baumberg. “The rest must be a properly balanced diet. either dry (biscuits), semi-moist (dog sausage) or canned food.”

[Chapter Break]

Arthritic Hands reach to touch the heads of whippets Jade and Celeste as they are led through the geriatric unit of the Pukekohe Hospital by their owner Merle Powley. A dog control officer with the Franklin District Council, Merle and fellow officer Deanne Hall have been taking dogs to visit patients for nearly two years.The scheme started first at the request of the hospital staff, and now it’s a regular friday event for patients, many of whom, in this area, are retired farming people. Today the dogs are looking out for the biscuits which some of the patients have saved from their morning tea. For many of the patients, seeing the dogs awakens old memories. They have stories about their own dogs, and as Jade touches his muzzle to the face of one of the older patients, tears run down his face.

“The patients like touching the dogs for their warmth,” says Chris Lawton, co-ordinator of community services in the Franklin health area. “We find with some of the ones who are usually abrupt that it brings out some gentleness, and relaxes them.”

Not in every patient though. As Merle approaches one pinkcardiganed woman in her wheelchair the patient suddenly, animatedly, comes to life. “Get them out of here, filthy things,” she says, her arms and legs waving in fury. Some of the others watch and smile. Having the dogs there provides entertainment, too.

[Chapter Break]

GO R-I-G-H-T Away, Bess! Go r-i-g-h-t away, Lad!” Spurred on by a couple of ear-piercing whistles, the dogs are away, coats glistening, racing up the hillside to outflank a distant mob of sheep.

“Walk up! Walk up, Lad!”

The familiar commands of the sheep farmer, employed, with variations, throughout the country, are as much a part of New Zealand’s heritage as whitebait fritters and Chesdale cheese.

In the main, New Zealand farmers use two types of dog: the heading dog and the huntaway. Heading dogs are direct descendants of the imported Border collie—small, long-haired dogs with a “strong eye” or stare which they use to stalk and hold sheep after they have rounded them up. It’s the wild dog’s stalk before

moving in for the kill that breeders selected for—without the final act. Even so, some strains still have the desire to bite. This tendency has to be controlled with sheep, but is often encouraged with cattle where these dogs are expert heelers—biting heels and then “swatting” or lying flat to avoid being kicked.

Heading dogs, sometimes called “eye dogs,” work without barking—probably a throwback to ancestral hunting days when noise would spoil the chase and reduce the likelihood of a catch. The herding, or “heading,” instinct is also a remnant of wild behaviour that has been selectively retained: wolf packs capture prey by fanning out to encircle it.

Pioneering New Zealand sheep farmers did not rely solely on the Border collie. Some preferred the Scottish collie—a bigger, hardier dog than the “creepy-crawly” Border, and with the stopping power to halt a big mob of sheep. There was also the bearded collie or beardie from Scotland, and the Old English sheepdog—before the fancy breeders got hold of it, selected out its working ability and made it wool-blind.

For all its merits, the traditional Border collie was not ideally suited to New Zealand conditions. New Zealand shepherds wanted a dog that would stand up on its feet and be seen by the sheep, which were not as wild as the Cheviots of England and Scotland, where stalking and eye contact were vital to hold them. They also wanted a smooth-coated dog to stand the heat, and a dog which didn’t sweep so wide as it gathered in the flock. So again, selection brought about the changes needed to meet the demands of the market. The “made in New Zealand” heading dog was officially recognised in the 1920s, and few of the old long-haired Border collie types can be found on farms today.

It was this diversity of heading dog genes that, ironically, became the foundation for quite a different type of working dog: the New Zealand huntaway. At the moment, New Zealand has no indigenous breed, but dog experts predict that should we eventually have one, this useful dog will be our first.

Nobody ever bothered to write down the recipe of how to make a huntaway, so we can only use conjecture about its history. It’s a classic mongrel—a mixture of many of the working dogs around at the time. As well as Border collie, beardie and Old English sheepdog, strains of droving dogs found around markets—the Smithfield, for example—found their way into the mix.

Labrador and hound genes were added at times, but never the German shepherd. The result was a large gene pool from which intense selection took place to achieve a breed which had only one requirement: the ability to work stock.

Looks were irrelevant, and in a way this was the huntaway’s greatest good fortune: no-one was interested in laying down rules about what a specimen of the breed should look like. There was no huntaway breed society, so breeding was left to farmers rather than committees, and if the animal didn’t perform it was disposed of.

The main feature of the huntaway is its ability to bark while it is working. It is trained to “face up” or stand, and always bark at the stock. Within the breed, huntaways are sometimes described as “straight huntaways” which are used for driving with force and noise, or “head and hunt”, which will do both jobs. Then there is the “handy” dog which will head, hunt, and do all the jobs needed around the yards and woolshed such as “backing”—jumping on the sheep’s backs to help push them into pens in the woolshed or clear blockages in the race. After a few beers at dog trials you will hear added to this list, bringing the paper from the gate.

The shepherd’s basic pack of, say, five dogs would be made up of three huntaways and one or two heading dogs. For most of the year the huntaways are the main workers on the farm. It is only in lambing time, when sheep have to be handled in smaller groups, or individual sheep caught, that the heading dog comes into its own.

Nothing incites a farmer to greater wrath than an incompetent dog, and a dog’s worst fault is its refusal to do nothing. “All accelerator and no brakes,” the shepherd complains as his dogs disappear over the horizon, ignoring a stream of commands to “Get in behind!” that increase in ferocity and colour. Because they are race team members, many dogs cannot bear to watch their fellows working while they have to sit still. When they do eventually return, usually having scattered the flock to the four winds, they get a boot in the curriculum vitae from their raging owner.

While most sheepdogs are raised on the farm by their owners, many also change hands—good ones for over a thousand dollars. Because each owner has a distinctive way of communicating with his dog, there is often a period of uncertainty and confusion while the dog gets used to the new owner’s commands and whistles. Some dog trainers supply a tape recording to help with the more detailed commands.

A big frustration for casual farm workers or visiting stock agents arises when they need to borrow a dog be-

longing to someone else, or command a strange dog in an emergency—such as when sheep are escaping. The dog will not work. It just stands there with its head cocked as though you were from another planet. The owner thinks it’s a great joke when told later—proud of his loyal mate.

One Northland farmer and engineer, Darcy Gilberd, who travelled away a lot and had other people moving his stock, solved the problem of multiple dog control by training his dogs to obey Morse code signals blown on a referee’s whistle. One long was to call attention, short-short to bark or “speak up,” long-shortlong for steady or, when repeated, to sit, long-long to go away, and long-short to come behind. All simple enough to get the dog to do the basics.

Most shepherds aren’t interested in such an orderly approach to dog commands. Whether they use a plastic whistle that you put inside your mouth and hold with your teeth, or blow through their teeth or fingers, to the shepherd a whistle is as much a statement of social prowess as the dog’s name.

Speaking of which, the ten most popular sheepdog names, according to the New Zealand Sheepdog Trials Association’s studbook, are currently Ben, Boy, Dick, Sam, Meg, Kate, Star, Sue, Flo and Chief.

Working dogs aren’t just found on farms. They seem to be taking an ever-increasing role in New Zealand society these days, in many cases the result of a decline in human behaviour.

Police dogs were introduced to the New Zealand Police Department in 1956 after Prime Minister Sidney Holland had seen them working in Britain. Two dogs were brought out to establish the police dogs kennels at Trentham—where all the breeding and training was, and still is, concentrated.

The German shepherd is used exclusively for police work in New Zealand because of its good temperament, agility, strength and acceptance of discipline.

While police German shepherds do drug detection work as part of their general duties, customs officers tend to use Labradors or smaller breeds for their work, as they have a less threatening public image when sniffing people’s luggage. Agility is paramount in drug dogs, as they have to climb over parcels on moving platforms and crawl into small spaces inside ships and aeroplanes. Guide dogs to aid people with impaired vision were first used in New Zealand by the Royal New Zealand Foundation for the Blind in 1958, with dogs trained in Australia. The first New Zealand-trained dogs went to work in 1973, and there are now 112 dogs working and 30 in training.

Special legal dispensation for guide dogs allows them to enter such places as shops and supermarkets—otherwise no-go areas for dogs. It is now an offence for a guide dog to be refused permission to enter any public premises, including public transport and aircraft. Such dispensation does not yet apply to dogs which help the disabled by pulling their wheel chairs or carrying their shopping bags.

Training guide dogs is an expensive business—around $15,000 per dog—and for a long time only a small percentage of dogs taken in for training completed the course. Now that the Foundation for the Blind’s Guide Dog Services unit has set up its own breeding programme, selecting for the important traits needed for this specialised work, the success rate has risen quickly, to around 80 per cent, and the unit is regarded as a world class facility. “We assess our dogs on 26 different aspects of personality and physical ability,” says Ian Cox, head of the unit. “We don’t want nervous dogs, nor excitable ones. They have to be able to concentrate for long periods, and be able to ignore distractions such as loud noises, or people patting them.”

The training programme starts at about 7-8 weeks of age, when the puppy is placed in a volunteer puppy-walking home for 12-18 months. Here it is exposed to and taught to cope with everything it could possibly meet in its later life.

Labrador retrievers and first-cross Labrador/golden retrievers are bred especially for the elderly, less able and multi-impaired applicants. But there are many other breeds and crosses that can be trained, including Airedale terriers, German shepherds, Dalmatians and even poodles (for applicants who are allergic to dog hair).

[Chapter Break]

Dogs,like humans, are a very adaptable species. They can reproduce rapidly, and respond well to natural or man-made selection. As a result, there is plenty of opportunity for man to change the dog—for better or for worse.

The working dog is by no means perfect. Some say it takes too long to train; today’s shepherds don’t want to spend hours after work and at weekends training their dogs. Others are concerned that the genetic base of these dogs may be getting too narrow, with the influence of too few top stud animals. They fear some inbreeding defect expressing itself in less robust animals designed more for the short run at the dog trials than the hard life on the farm.

There’s certainly plenty of technology waiting to be used in future dog breeding. Artificial insemination methods developed at Massey University are among the most sophisticated in the world. They will allow breeders to have access to the top genes in a breed, wherever that may be in the world.

Egg-splitting to produce clones of identical animals, and embryo storage and transfer are also a reality, while the ability to move individual genes around by genetic engineering is just around the corner.

Despite the technology, little interest has been shown by the scientific community in our stalwart sheepdog. I for one believe that the working dog is taken for granted—and that is not good enough for an animal that has helped make this country. The monument at Tekapo is maybe not prominent enough—it should be outside parliament!

New Zealand has a very high health status in the world, and could become a genetic reservoir and storage repository for the world’s top working dog genes—and that includes all dogs classed as workers. There is no reason why we could not become the Mecca for working dogs, as we are for shearing.

For the non-working dog, the future is going to be one of increasing conflict between genuine dog-lovers who look after their animals and pay their dues, and those who do the opposite. Laws and bylaws will increase, and the cost of their administration will add further burdens on the innocent.

It doesn’t need any great vision to predict this. All you need to remember is the love/hate relationship between dog and man, and the simple fact that most people still see the owning of an animal as a right and not a very special privilege.