Taxi

Hail a cab in Auckland or other large New Zealand centre and, chances are, the driver will be from Asia, particularly from the Indian subcontinent. Immigrants have become a major force in taxi industries the world over, but how has this come about locally?

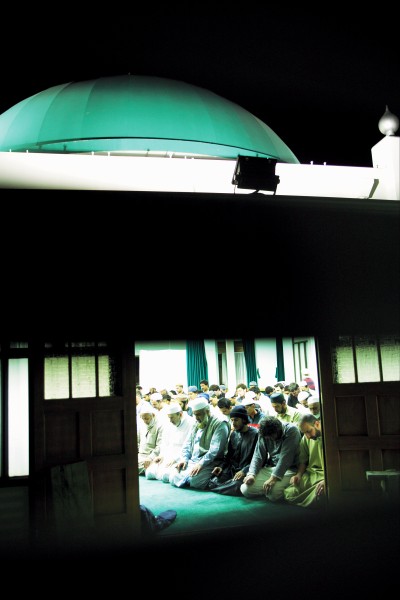

An hour after sunset the air is still warm and the light muted. A sickle moon glows brilliantly over the mosque, casting a faint trickle of light down the dome and upon the white caps of the men pushing through the doors. A slender line of women in chadors slips silently around the throng, up a rickety stairway and into an upper room; out of sight and, presumably, out of mind.

A swarm of taxis is parked along the curb as if washed up by a great wave, and still more press bumper to bumper in the narrow street to find a park. Latecomers bundle through the doors and squat on a broad tiled floor to wash their hands and feet, then shuffle discreetly into the main chamber.

I follow with a shallow bow, feeling like an impostor, and, muttering salaams, find a place in a back corner—close enough to feel wholly (and conspicuously) involved, but far enough away that I can leap through a window should my courage fail.

The air seems charged with faith. Lines of devotees gather beneath the fluorescent lights and the long, mournful chants of the mullah. He raises his voice in a shrill and beautiful cry, in measures indecipherable to the Western ear, then stops abruptly to let the echoes from the dome rain down upon his congregation. In unison they squat, roll forward on the balls of their feet, place their hands to the green carpet and press a hundred foreheads lightly to earth, whispering incantations.

They are prayers of hope, of their wish for prosperity in a new life in a new land. Collectively they represent every shade of Islam, many from countries that are intermittently at war with one another, often divided, ironically, over nuances of the very faith they share.

Tonight is one of the holiest in the Islamic calendar: the 27th night of Ramadan, when the Koran was revealed to the prophet Mohammed. It is a night of great piety, when believers count their blessings and remember what it is to be Muslim. Tonight they pray side by side, bent double in a room on the far side of the world, in a plush society lane in Ponsonby, Auckland.

[Chapter Break]

Conflict is between countries and politicians, not between people,” offers Altamash by way of explanation, “so in the new country we put aside our differences.” He sits next to me after the prayers, his eyes sparkling under thick-rimmed glasses, and a Co-Op Taxi pin proudly displayed on his breast. Next to him is Saleem. He’s an Economy Taxi man, as is Dariq. Everywhere I look there are taxi drivers, as if I’ve just happened upon some secret union.

There is no Islamic community in the central city, so the Vermont Street mosque caters almost entirely for working Muslims, a remarkable number of whom are taxi drivers. The air rings with chatter about the Land Transport Safety Authority (LTSA) and Passenger Service Licences (PSLs), while recently closed city ranks are a topic of particularly hot debate.

I am invited to eat and to talk, and I discover during the conversation that, despite living in New Zealand for many years, some migrants still feel in their adopted country as I do in their midst: like impostors. But within the broad community of immigrant taxi drivers there is cohesion.

Pakistanis eat beside Indians, and Shi’as with Sunnis. In fact, it seems as though a greater distinction is made between the companies they drive for than their ethnicities.

Driving cabs is a preferred profession for many immigrant Muslims, allowing free time for family life and prayer, or the tertiary study required for recognition in New Zealand of overseas qualifications. And taxi companies are more than willing to oblige, for Muslim drivers don’t drink and are happy to work evenings and weekends at competitive rates, factors that have seen many European New Zealanders displaced from the industry.

Khurram Zaidi waits on Wakefield Street, his taxi languishing under the orange glow of sodium lamps in a five-minute park. Behind him is the Hollywood-inspired Village Cinema, the Aotea Centre and the iconic syringe of Auckland’s Sky Tower. This is a lonely realm of half-light and half-witted passengers, of sidewalk clashes, racial slurring and the barely perceptible tick of nocturnal hours.

Yet Khurram has little choice but to be here. Despite having an MBA and extensive experience in Pakistan’s banking industry, he has been driving cabs for two-and-ahalf years. Before emigrating to New Zealand he checked out the job market on the internet and saw many jobs that he could confidently apply for. But finding work once in New Zealand proved very difficult. “It’s not that I’m not fit for the job, and it’s not racism either; I just don’t understand the kiwi culture and networks well enough,” he says, his voice tight with evident frustration.

The bank that Khurram was working for in Lahore had more than 800 staff, but in New Zealand he found a very different business environment. His MBA meant little. “In Pakistan you show your degree, here in New Zealand you have to show skills; you have to do everything practically and have to prove yourself under constant observation.”

[Chapter Break]

It’s 4.30 p.m. on a Wednesday afternoon in New Lynn. Shahid’s curtains flog in the hot afternoon breeze. He was up all night watching the Pakistan v. West Indies one-day game and still keeps a distracted eye on the telly, which is playing highlights some 18 hours later.

“You must understand, James, we’re just mad about cricket,” he says with one of those diagonal “Yes/No/I understand/I have no idea what you’re talking about” nods of the head that confuse anyone trying to converse with a Pakistani.

He explains in depth about the total collapse of the Windies’ lower order that allowed his countrymen to steal an impossible victory. And he lives the moment again with a boyish grin.

Shahid Azad calls himself a “pakiwi”, a proud New Zealander of Pakistani origin, and in recent years has done much to strengthen the growing Pakistan Association of New Zealand. “The government encourages these ethnic communities to be sincere about their culture and sincere about integration with the rest of New Zealand. There can be a very good exchange of ideals and traditions.”

Shahid wears an immaculate lemon-coloured shalwar kameez with gold buttons down the front and decorative lacing on the sleeves. He’s well-groomed and well-spoken, and considers each of my questions carefully before he answers. Perhaps it’s his training: Shahid holds a masters in English literature and political studies and was lecturing in a postgraduate college before he came to New Zealand in 2001. And, he quietly admits, he composes romantic poetry in his spare time.

But between duties as the president of the Pakistan Association and penning Urdu sonnets, Shahid also drives taxis and runs an elaborate joint venture with a friend importing Japanese cars. In fact, during our interview he critiques my car parked on the roadside, offering to pick up a new one for me at a very reasonable price. I gratefully decline.

Our conversation ranges from Imram Khan’s infamous pace bowling to the hunt for Osama bin Laden—defining features of Pakistan’s international image. But the connection with terrorism upsets Shahid. “Especially after 9/11 there are so many misunderstandings and misconceptions from media reports,” he says. “And you know, the media is powerful in Western countries; people in New Zealand listen and accept what is said. But Pakistani people are very hospitable and any small minority shouldn’t be generalised.”

Over a cup of hot milky chai Shahid explains his motives for leaving Pakistan. “I came to New Zealand to do a PhD, for an opportunity to extend my education. But there is another reason for leaving as well,” he says, and pauses to compose his next sentence tactfully. “Like other Third World countries, Pakistan is struggling with problems of corruption, injustice and inequality. And if you have any sense of right or wrong, these things frustrate you greatly.”

[Chapter Break]

The Pakistan Sports Club cricket team assembles at the edge of the broad grassy pitch in Mount Roskill. Actually, it has the air more of a family than a team. Although most of the players have no relatives in New Zealand, they share a great sense of camaraderie, of familial warmth. And, without exception, every member of the team was driving a taxi until early this morning. Asad got home at 6.30 a.m. and Adeel fell into bed at 8 a.m. Now it’s 3 p.m. and last year’s tournament champs are looking a little foggy.

The team captain, Wasim, managed to get home at the more respectable hour of 4.30 a.m. “We don’t come to New Zealand for fun,” he says. “We all have our extended families back at home, and most of us look after more than one family, especially if we’re married.”

Wasim and his team-mates each send home $700–$800 a month. “We never feel that it’s a burden, it’s just part of our responsibility,” he explains. The income Wasim makes driving cabs and importing used Japanese cars has also helped his two brothers to start businesses back in Pakistan.

On the field Wasim distributes his team in scientific fashion and the umpire tosses a match ball to Pakistan’s pace bowler, Asad. There’s a hush as the Sri Lankan batsman takes his stance at the crease and stares down the Astroturf pitch. The umpire nods, and Asad begins a long run-up over a measured distance. He passes the stumps with a single long stride and bowls a text-book outswinger that whistles past the batsman untouched. “Shaabaash, Asad.” Well done.

Asad returns to his mark, licks his fingers, polishes the ball beside his crotch as cricketers are wont to do, and wipes the fatigue from his eyes. The next three balls are wide and the fifth is knocked to the boundary.

The fielders also seem to be below their best. Dropped catches and misfielding allow the Sri Lankan team to quickly notch up runs with a salvo of boundaries so that, by the end of the innings, Pakistan is facing the almost insurmountable target of 170 runs.

Asad has no family in New Zealand, “just me and my-self”, as he puts it, dragging on a cigarette between innings. He is studying network engineering at the Manukau Institute of Technology, building on his computer-science qualification from Rawalpindi, but is deeply concerned about his job prospects. “I don’t want to drive cabs for the rest of my life.” He pulls leg pads out of the boot of his taxi. “There’s no respect in it—the amount of abuse you get from people.”

Wasim dons a helmet, straps on his pads and rallies the troops on the sideline. One hundred and seventy-one runs to accumulate in just 20 overs. Confidence is waning a little but the captain remains upbeat. He anticipates a mighty comeback.

[Chapter Break]

Hot fatty air pours from the vents of swanky Viaduct Basin restaurants onto the taxis queued along Sturdee Street. Rain pelts down. Drivers huddle in their cabs or line up against the wall of the Loaded Hog, hoping that mere proximately to the building will keep them dry. Others squat in a bus shelter.

The waiting cabbies’ quiet manner belies a sinister sense of competition among them.

Reckless deregulation of the taxi industry has created a dark urban battleground where 48 companies now vie for inebriated patronage, with fare wars and common skulduggery part of the fabric of daily life. The nuances between what is legal and what is illegal are absorbed by shadows and the shuffle of a somnolent city.

Drivers today must contend with aggressive monitoring by the LTSA, hounding by the Inland Revenue Department (IRD) and a continuous bombardment of traffic-offence tickets from the police. That’s before a customer steps off the footpath, which is when for immigrant drivers some of the biggest problems start. Language and local-area knowledge present one set of challenges, but Friday-night fares from the city can inflict a gamut of tribulations, from the incoherence of the sleeping drunk to the violence of abusive thugs.

Patel Kinsal was admitted to hospital a bloody mess of head wounds and bruises after a fare went bad. A couple of drunks hauled him out of his cab, broke his nose and beat him senseless. Patel has no idea what provoked the attack, is scared to drive again and certainly won’t be on the street at night.

It’s against this background of racial abuse and financial struggle, therefore, that desperate drivers augment their income with distinctly shady practices. “I’ve described it before as a black market, but it’s not; it’s more like a Mafia,” says one disenchanted cabbie. In fact some insiders believe that Auckland’s taxi industry is built on systemic corruption, traceable all the way to a handful of operators who control the lion’s share of the market.

After deregulation in 1989, the number of cabs on Auckland’s roads tripled and New Zealand became a safe haven for illegal operators keen to make a quick buck and get out. In 1997, the Pakistani-owned company Ideal Cabs began signing up drivers for free, which revolutionised the industry almost overnight. It was closed down by the LTSA because of its total lack of financial control, so it packed up and took its business to Australia. Black Cabs, also owned by a Pakistani family, was shut down too, but, in the finest traditions of intergenerational corruption, the business was simply transferred into the name of a son.

Even the massive Economy conglomerate has recently been through a physical audit by the police, LTSA and IRD. According to one cabbie, “It gave the drivers a scare but they’re all back on the road now, with new plate numbers and the same old fraud.” Some were forced to register for GST under a system of willing compliance, a general amnesty whereby the IRD cleared a driver’s slate in exchange for full disclosure. But just weeks later, the driver needed only to cancel the GST number and transfer his business into someone else’s name to start afresh.

Greedy taxi companies and desperate drivers use a great array of illegal ploys to syphon cash from the system. A driver must have a PSL to operate his own vehicle as a taxi. But a growing number of companies register drivers’ vehicles under their own PSL, a sleight of hand that allows drivers to avoid licensing costs, hide their earnings and receive social welfare at the same time. In exchange they pay the taxi company “risk money” to cover their criminal liability.

In the worst cases a driver will also collect a sickness benefit (often for “back trouble”), send his wife to Work and Income New Zealand to claim single-parent status and thus get a housing allowance, and run a stall at the Avondale flea market for cash on the weekends. It’s a lucrative scam that has been tried and tested.

[Chapter Break]

Abdul Qazi sits behind a desk swamped with paperwork and scribbled notes. His five-o’clock shadow blends into greying sideburns. Our interview is punctuated by numerous calls on a couple of phones, and I soon realise that he is running Dial-A-Cab and despatching vehicles single-handedly. He is visibly tired and deeply frustrated that the industry he has invested his life in seems to be spiralling out of control.

Qazi holds two passports: one from his adopted homeland of New Zealand, the third-least corrupt country on Earth, the other from Pakistan, the third-most corrupt. It used to be a bit of a joke with his friends, but he no longer finds it funny. “This is a cancer; some immigrants have brought their corrupt values with them. They don’t want to rob a bank, but they’re happy to rob the system”. There is little doubting the devotion of immigrant Muslims to the tenets of Sharia Law. But laws of the land are prescribed by man, not God, and some choose to interpret man’s laws more liberally.

Dr Ashraf Choudhary MP is a slight, silver-haired man with an easy presence and a very practical grip on the realities of life for new immigrants. “New Zealand is a law-based country; we have rules and those rules must be followed,” he says. “But on the Indian subcontinent the rules in the book are often disregarded or not fully regarded. And I think new immigrants from those countries get a shock when they discover that in New Zealand they actually have to respect the rules.

“At high school back in Pakistan someone asked me if I’d ever travelled outside my home town. I hadn’t, of course, and the guy remarked that I was like a frog in the well—stuck in my own world with no way out.”

The comment clearly made an impression on the young Choudhary, who went on to study for a Masters degree in the UK and a PhD in agricultural engineering in Palmerston North. “I would never have thought in my wildest dreams that I would become a professor in New Zealand, or that I would be a Member of Parliament.”

When he arrived in the country—after three-and-half years of cultural acclimatisation in England and with a job already lined up— there were only a handful of families of Pakistani origin in New Zealand. He admits that the situation immigrants from his home country find on arrival is very different from what they are use to. “There is no social welfare structure in Pakistan, so new migrants are not used to living on the dole. And it’s not really culturally acceptable to them—they are very proud people.”

But the taxi industry provides a good alternative to government hand-outs. Abdul Qazi recalls a time when he had nearly 100 Bangladeshi doctors driving his cabs. Many are now registered practitioners in New Zealand, with the balance in the medical field in Australia. For them, driving taxis was a means of generating a decent income while studying. It was a genuine leg-up to a new life.

The taxi industry has occupied such a place in the social economy since immigrant Chinese in India first started running rickshaws on the avenues of Simla. Soon it provided rural Indians with gainful employment in Calcutta, spurring the urbanisation of a nation. Today, taxis in every developed city in the world are driven largely by immigrants, while in developing nations the industry creates opportunities for the new middle class.

[Chapter Break]

The wind swirls street dust into great eddies that twist into the heavens and muddy the air. It’s 38º C in the shade, which, incidentally, is where I am, slumped on the back seat of a dilapidated taxi rattling through the back streets of Rawalpindi. I’m just 20 minutes from the manufactured capital of Islamabad, but the view from the window is of a very different place. These two cities are like chalk and cheese: Islamabad the new, muscular metropolis of a burgeoning Pakistan, veritably busting with ambition; and Rawalpindi the old, bedraggled drop-out of a city, clinging to the mainstays of industry and poverty. Movie stars and presidents visit Islamabad; refugees and the army squat in Rawalpindi.

Farooq drives his clapped-out Corolla taxi between the two, taking the glitterati from Islamabad International Airport to the Marriott and then on to his uncle’s shop in a burnt-out alley of Rawalpindi, where he earns a cool commission for their patronage.

This is how the system goes in Pakistan. A wink, a “My friend, my friend”, a carefully massaged white lie, and there you are, 20 minutes from your desired destination with Farooq sliding 1000 rupees into his shalwaar kameez.

But he does it well, in a charming, endearing, forthright kind of way that leaves you thinking, “Farooq, you old dog, looks like you got me on that one.” And I think he rather fancies himself as a Robin Hood of the modern Pakistan, redistributing wealth from Islamabad to Rawalpindi, from right hand to left.

Farooq is one of Pakistan’s new middle class. By driving cabs and using his cunning to extract a cut from his uncle, he’s levered an education for his children, an education that will give them jobs in the new Pakistan.

In his wallet he keeps a worn photo of his kids and a bundle of business cards that reads like a who’s who of international journalism. All the card owners have ridden in his taxi while covering the US invasion of Afghanistan—and, no doubt, have taken an unexpected excursion to his uncle’s shop.

As I return with Farooq to Islamabad, the vista changes markedly. It’s like a before-and-after on one of those ridiculous weight-loss billboards. Rawalpindi—Pakistan now—dirty, disorganised, poverty-stricken. Islamabad everything Pakistan wants to be—clean, modern, powerful, hand-in-glove with US foreign policy. And barely 15 minutes away. It’s a scale model of the new Pakistan, glistening with all the trappings of modernity.

And Farooq wants a part of it. Everybody wants a part of it. Some wait in Rawalpindi for the inevitable merger of the two rapidly growing cities, while others, like Shahid Azad in Auckland, have enough gumption to travel to New Zealand, half a world away, for a slice of the Western pie.

[Chapter Break]

In New Zealand, Shahid develops programmes that help new migrants from Pakistan adapt and integrate. Activities range from sending the bodies of deceased members back to Pakistan for ritual burial, to community education on issues of racism and tolerance.

But the insights he has gained in New Zealand have only made him desire the same transparency back home. “I have learned a lot. Doing political studies I examined Western democracy and its political institutions. But experiencing these things first-hand in New Zealand, I realise that this is what I want to see in my own country. Here you can get justice, you are free, you can say anything you want and you can expect basic rights. In Third World countries these things are almost non-existent on any practical level. So being in New Zealand, the desire to see this prevalent back in Pakistan is very much sharpened.”

Back at the Mount Roskill cricket ground the Pakistani batsmen’s late-night taxi-driving is beginning to tell. Asad is caught out with 39 runs on the scorecard and the captain, Wasim, is dismissed after chalking up just 14. The wickets start to tumble. Rashid is bowled in spectacular fashion, and when Iftikhar goes for a golden duck, the team’s demise is inevitable.

On the sideline the lads shrug and mutter, and even before the last over has been bowled begin packing gear into the array of taxis parked nearby. It seems that the Pakistan Sports Club cricket team has more sleeping and less driving to do before achieving success on the pitch. But I guess that’s not what they’re here for. The coming week will bring more driving, more study for some, and a continuation of the relentless struggle to balance family commitments in Pakistan with a livelihood in New Zealand.

They have come to this country to mortgage their youth for a place in the modern world, to earn the sort of life for themselves and their children all New Zealanders dream of.

Ashraf Choudhary looks to the billowing cumulo-nimbus clouds building on the horizon, as if gazing back through three decades in his adopted country. “My dream is to see these new migrants as full participants in our democracy, that they feel proud being New Zealanders and integrate into society.” He pauses, perhaps dwelling a while on his own experience, before summing up: “They’re not just economic migrants, they’re here to make New Zealand their home.”