Taniwha

Deep in our lakes and rivers lurks a monster that has become the stuff of countless myths and legends. But now, just as this misunderstood creature is starting to reveal its many mysteries, some are questioning its future. Enter the dark realm of New Zealand’s largest freshwater resident, the longfin eel.

It was a calm summer day in 1963. Bev Haines was sitting in a dinghy on Lake Rotoiti in Nelson Lakes National Park, waiting for her husband, Clinton. “There had been a boat race the previous week, and one of the boats had lost a propeller,” Bev recalls, “Clint wanted to retrieve it so he went diving.”

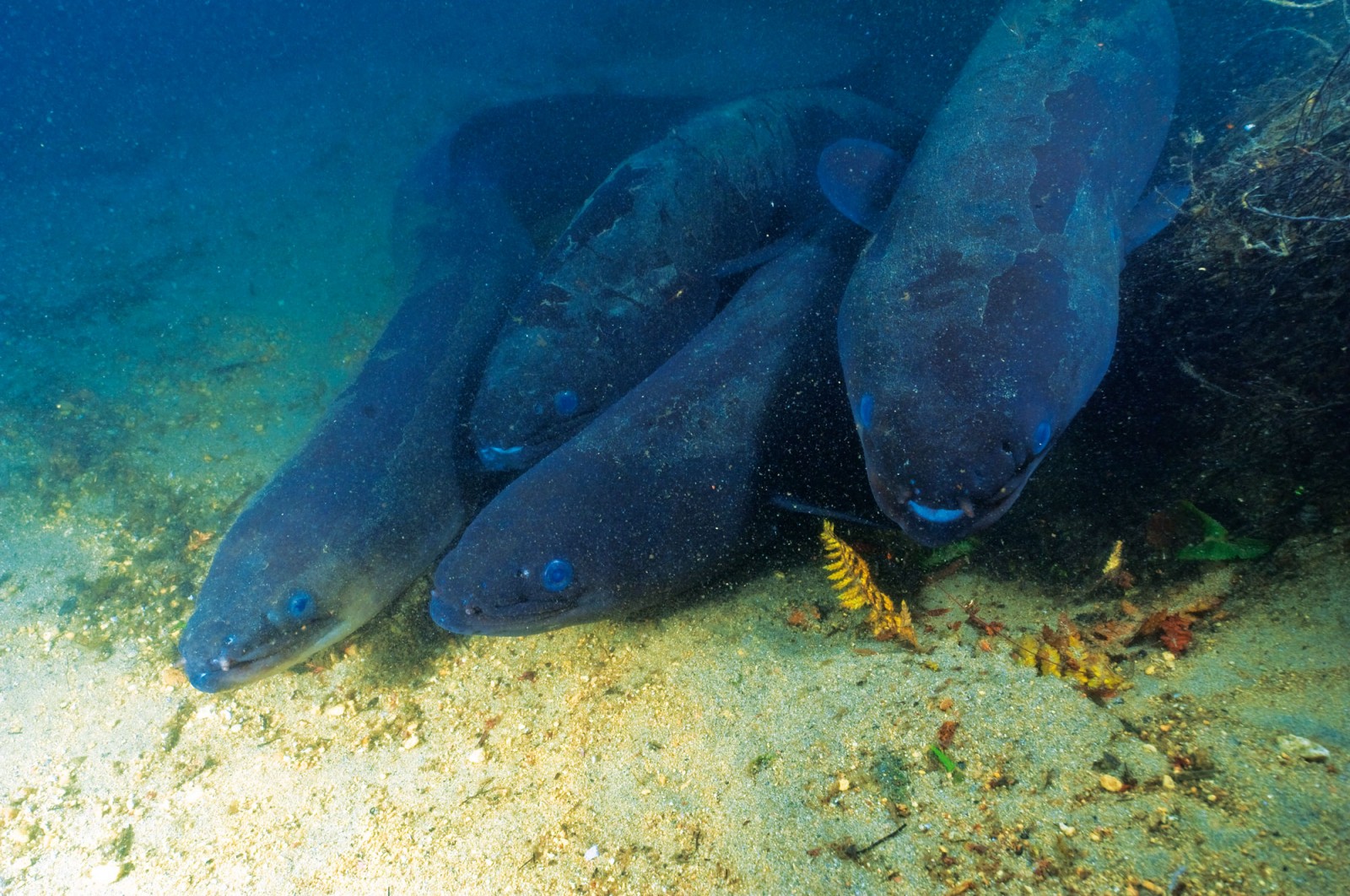

Lake Rotoiti is by no means shallow—gouged out by glacial forces, its alpine shores sink steeply into the depths. Clinton had made it down to about 100 feet when, out of the gloomy water, he saw a dark shape looming towards him. He drew his knife to defend himself, but then noticed three or four more large creatures coming straight at him. Terrified, he shot up to the surface.

“By the look on his face, I knew straight away that something was wrong. Then I saw them—massive, snakelike creatures in the water. One of them had a hold of his flipper.” Charged with adrenalin, Bev managed to pull her husband to the safety of the boat, and rowed towards shore. As a result of his quick ascent, Clinton was suffering from a mild case of the bends. He went to hospital and spent the next two days recovering in bed. But the psychological healing took a lot longer.

“For months, we both had nightmares. I wouldn’t go back in that water, not with those things there,” he says.

The creatures Clinton Haines had encountered that day in Lake Rotoiti were not exaggerations of an overactive imagination, but New Zealand’s very own and very real freshwater monster, Anguilla dieffenbachii, the longfin eel. Two other species ply our fresh waters—the shortfin eel (A. australis) and the Australian longfin (A. reinhardtii), a recent arrival currently restricted to the northern part of the North Island. Of the three, the New Zealand longfin is the most impressive. Described by those who have seen them as “logs that moved”, there have been confirmed sightings of specimens up to two metres in length—much longer than Haines is tall—and weighing up to 40 kg. In fact, scientists believe that our endemic longfins are quite possibly the largest eels in the world.

Their gargantuan size is not the only thing that makes longfin eels inherently disconcerting. There’s their serpent-like appearance—an elongated body which slides through grass when migrating from one waterway to another as easily as it slithers through streams. Equally unappealing is their leathery skin, which—although embedded with hundreds of tiny scales—is covered with a thick layer of slippery slime.

The animal’s seemingly antisocial behaviour also contributes to its image problem. During the day, an eel will hide under logs, boulders and riverbanks, coming out only if lured by the smell of blood. It actively seeks the inky waters of the deep, and prefers to hunt under the cover of night. Black colouring completes the eel’s dark disguise, enabling the animal to become one with the background as it snakes through its liquid medium. Consequently, human encounters with eels are most often like that of Clinton Haines: sudden, unexpected and frightening for as long as the memory endures.

[Chapter break]

Although eels were an important food source that allowed Maori to settle further inland, the country’s first occupants revered as well as feared the large longfins. Some rivers, lakes and caves were declared tapu, believed to be the home of water-dwelling monsters, or taniwha. Even now, access to certain areas is restricted or forbidden, because a taniwha is said to inhabit the water.

“We have a lake near here where we don’t go,” Pataka Moore, a lecturer in environmental sciences at the university at Otaki, Te Wananga-o-Raukawa, told me. “Every hill and tree and stone has a story in our region, but there are no stories at all associated with that lake.

Many terrible things have happened to the people who have gone there; people have died.”

Moore recounts stories of drownings and accidents; the most recent incident involved a man who badly injured his arm while swimming in the lake. “Some people might argue that he got tangled in branches,” Moore said, “but there are those of us who know it was a taniwha in the form of an eel.”

When Europeans arrived, they too feared the snake-like creatures that inhabited their water supplies. Unexplained disappearances of bushmen and recreational swimmers were often blamed on packs of hungry eels, giving rise to countless tall stories. The fact that the monsters in question manifested themselves only briefly before disappearing back into the deep made them all the more loathsome. Even now, mention eels and some people will instinctively recoil: eels are ‘yuck’, ‘slimy’, ‘horrible’.

On a biological level, a healthy apprehension of longfin eels is a rational reaction. “They’re an incredibly powerful predator,” says Vic Thompson, who has commercially fished longfins for the majority of his life. “If you were to enter eel-infested waters with a couple of mackerels stuffed down your shirt, you’d be in serious trouble.”

Eels are finely honed to make them extremely efficient hunters. Because of their desire for the dark, eels rely on a hyper-sensitive sense of smell rather than sight to locate their prey. Sizable “horns” on their upper lip support a large, folded nasal cavity that extends to the roof of the mouth. This endows the eel with olfaction several times greater in magnitude than even that of a great white shark. In fact, scientists have calculated that if you were to tip just one millilitre of blood into a lake 48 times the volume of Lake Taupo and mix it around, the eel would still be able to detect it.

The longfin’s feeding mechanisms resemble that of another top predator, the crocodile. Like their reptilian counterparts, eels are classic ambush predators, concealing themselves and lunging at hapless victims as they pass. The suction created by the mouth allows the eel to virtually inhale its food.

To dismember a larger animal, a longfin will first clamp onto a carcass with rows of small but sharp teeth, using the force of its jaw to achieve a vice-like grip. It then starts spinning its body in crocodilian fashion, twisting and rolling until a mouth-sized morsel has been torn away. Its stomach is highly extendable, so the eel will feed until it has gorged itself with food.

So are we in danger of becoming fish food the next time we take a refreshing dip in a lake? Thompson shakes his head. Although large longfins are opportunistic feeders, and will investigate anything bleeding in the water, they generally live on a diet of live fish, freshwater crayfish and the occasional duckling.

That’s not to say there haven’t been run-ins. In 1973, a diver fixing a gate at the Arapuni Power Station on the Waikato River had two ribs broken when he was charged by a large longfin. An even more unfortunate tale involves a Southland farmhand who decided to go for a skinny dip and was subsequently hospitalised after an eel latched onto a sensitive area.

Predictably it’s fishermen who are the most frequent victims of eel attacks, bitten where their clothes have been smeared with the blood of their quarry. But if you question the context of these “attacks”, you soon realise that blame often lies not with the eel but with the lack of common sense on the part of the human. The Arapuni diver, for example, was charged only after a colleague took it upon himself to hit the eel’s tail with a hammer.

In fact, there is not one confirmed record of eels fatally harming a person, but we have not treated them with the same level of respect. Persecution began in the 1930s, when the Acclimatisation Society—the forerunners of Fish and Game Councils—claimed that eels were having a negative impact on exotic sport-fish populations. Bounties were set in an attempt to rid entire river catchments of their native inhabitants, and some areas boasted high levels of “success”. Masses of eels were caught, killed, and left to rot. Ironically, subsequent research showed that exterminating eels from rivers was actually detrimental to trout stocks—although there were more trout in the absence of eels, they were smaller and in poorer condition, not the trophies that game fishermen lusted after.

Then came uncontrolled commercial fishing. The eel industry was established in the 1950s, and by the 1960s thousands of tonnes of eels were being systematically slaughtered to feed the hungry European market. Commercial catches rose steadily, and by 1975 eels were the most valuable fish export after rock lobsters. There was no quota system, and any size of eel could be taken. The biggest eels were at the top of the hit list—having evolved as top predators, they had nothing to fear and were usually the first to be caught.

The repercussions of exterminating the big eels were not fully realised until a decade later. Although it was long known that big eels were females and spawning only occurred once at the very end of their life, it wasn’t until the 1980s that scientists discovered that it can take 80 to 100 years for them to reach that size.

Due to a lack of natural predators and low water temperatures, longfin eels grow very slowly, about two centimetres a year in the South Island. Males reach about 75 cm in length before they head off to spawn. In contrast, the females tend to stick around for almost twice as long; the bigger a female grows, the more eggs she will produce. No one knows exactly how old these grand dames get, but by counting the tree-like rings on the otolith—small, calcified bones in the ear—scientists have found that the eels of Lake Rotoiti where Clinton Haines came across his monsters live to at least 106 years.

Even at that ripe old age, all eels in New Zealand waters are still virgins: only at the end of their life will they produce young.

Before they do so, they undertake a monstrous journey that takes them thousands of kilometres into the tropical Pacific Ocean.

How an eel decides that it is ready to spawn is not understood. What we can be sure of is that every year, longfin eels all over the country begin an amazing transformation, one that prepares them for the transition from their freshwater hideouts to the salty void of the ocean.

“The eel’s head gets smaller and bullet-like, and the top of its body becomes very dark for camouflage,” says NIWA eel expert Don Jellyman, who has been studying longfins for almost 40 years. “To give the eel greater capacity to see at depth, the eyes enlarge to up to twice their normal size.”

By April, countless individuals have left the lakes and streams that have been their home for decades, to migrate downstream and into the ocean. “At this stage they are no longer feeding; for the rest of their journey they will rely solely on fat reserves,” Jellyman tells me.

The males are the first to leave our shores (their smaller size means it will take them longer to travel) and a month later, in May, the females follow.

Only females too large to be taken by black shags or other predators will venture out between dawn and dusk.

Where exactly longfins breed remains a mystery. A few years ago Jellyman released 10 female longfin eels with pop-up satellite tags into the sea off Lake Ellesmere on the Canterbury coast. The tags record several variables, including the time at which the sun rises and sets, information used to calculate latitude and longitude. But his efforts to track the eels were thwarted by a surprise finding: migrating eels remain in perpetual darkness.

During the night they travel close to the surface, around 200 metres deep. During the day, however, they move to a depth of up to a kilometre.

“Why they do this, I’m not sure, but it could be that they are following temperature bands to help control the final stages of egg development,” Jellyman says. Although he was unable to accurately follow the eels’ progress, a tag popped up just north-east of New Caledonia more than five months after its host had left New Zealand. The information that it contained, plus recent computer simulations of larval drift, suggest that spawning occurs near Tonga. After the eggs are fertilised, it is believed that all the adult eels die, in their multitude.

The baby longfin’s journey back to New Zealand waters is possibly more incredible. Eels start out life as tiny, toothed larvae called leptocephali, which form part of the plankton. Although no one has ever identified longfin leptocephali in the wild, they are believed to resemble those of other eel species: flat, transparent and shaped like a leaf. Although there is no doubt that leptocephali make use of near-surface ocean currents to drift back to New Zealand, computer simulations suggest that none would ever reach our shores if they relied on passive drift alone.

“Our modelling indicates that they must actively swim,” says Jellyman. But they must also be able to navigate.

“When you consider that juvenile birds that have hatched in one corner of the globe are able to migrate across oceans to a place they have never been before, then it’s not so implausible,” Jellyman argues. “We’ve found magnetite crystals in the cranium of glass eels, which may respond to the Earth’s magnetic field in some way.”

After seven to nine months in the open ocean, leptocephali reach the continental shelf, where they transform into translucent glass eels. They arrive on New Zealand’s coast between July and December, with numbers peaking in spring—the time of whitebait migration. Under the cover of night, the wriggly little critters gather and ride the spring tides in to shore. Once in fresh water, glass eels develop into darkly-pigmented juvenile eels, or elvers, which congregate in summer and begin a mass migration far upstream.

Sex is not determined until the eel is about 10 to 12 years old and has reached a length of 30 cm. Whether it becomes male or female largely depends on how many neighbours are around: crowded areas generally lead to males, and areas of lower eel density—such as inland lakes and streams—tend to favour females. Although they are not territorial, when a large female comes across a deep pool she will often set up long-term residence, provided there is sufficient cover.

Finding a suitable place to call home is one of the biggest challenges that longfin eels face. Only 33 per cent of New Zealand is protected as conservation estate; the rest has been subjected to high levels of modification. The straightening of rivers, construction of water races and removal of weeds and vegetation along banks may be of benefit to farmers and developers, but for eels that rely on those areas for food and cover it can be a death sentence.

“Countless eels are killed through habitat destruction each year,” admits Greater Wellington Regional Council scientist Alton Perrie. “But very often it occurs on private land, where no one sees it or can do anything about it.”

Not so in March 2008, when an earthmoving contractor was caught red-handed. In the process of removing and dumping weeds from a 300-metre stretch of stream near Lake Wairarapa, Gary Pilcher killed thousands of eels, from babies the size of a bootlace to longfins in excess of a metre. Although the farmer who employed Pilcher was prosecuted in April 2010, the contractor’s attitude at the time of the eel kills lacked any regret. As he told the Wairarapa Times-Age: “When a blocked drain is holding up production, I don’t give a fat rat’s arse about the eels. I don’t care.”

Unfortunately, for many decades this was also an attitude adopted by most of the country’s major suppliers of electricity, responsible for blocking an estimated 35 per cent of eel habitat with hydro-electric dams.

“When Matahina Dam was first put in, the place was just absolutely black with elvers trying to get upstream,” says Bay of Plenty resident Bill Kerrison. “They went straight up the dam and across the main road to the lake. It was beautiful but also devastating to watch, because as soon as it got sunny they dried out and died.”

A fish passage was put in, but like at many other dams around the country, it never worked. “At the start, the power company just didn’t put any effort in,” says Kerrison. After years of discussion, Kerrison is now employed to move 4.5 tonnes of elvers every year past Matahina Dam through a trap-and-transfer programme.

“My wife wants me to retire, but I just can’t. We know exactly how to handle and transport the little fellows, and we’re involved in their monitoring. They need us.”

For migrant females that need to get downstream, the dangers that dams pose are a lot worse. Although Kerrison and like-minded individuals transfer as many egg-laden females as they can, the majority of eels are forced to find their own way past the dam. Because of their large size, and the fast rotation speed of power-station turbines, the chances of a mature eel making it through alive are virtually nil. The eels are sliced up and killed.

[sidebar-1]

So it’s somewhat morbidly ironic that the largest of all New Zealand’s hydroelectric power stations, at Manapouri in Fiordland, sits smack in the middle of the most significant, unexploited longfin eel population in the country. The dam is built underground on the western arm of Lake Manapouri, and its out-flowing current fools migrating females into believing that the man-made tunnel will provide them passage to the ocean.

“It’s very sad, because there is a safe way out of the lake, down the Waiau River,” says Evan Brunton.

Once a commercial fisherman, Brunton has devoted the past eight years to saving the eels he once hunted. As part of his work for NIWA, he annually fits about 60 migrant females—those about to leave for their breeding grounds—with acoustic transmitters. Unfortunately, the statistics are not good.

“What we’re finding,” says Brunton, “is that more than 40 per cent of these girls don’t find the natural outlet, and end up as mince meat.”

The pressures placed upon longfin eels have taken their toll. The number of large females has decreased significantly, and recruitment—the number of young fish that enter a population in a given season—has substantially dropped. Yet commercial fishermen harvest up to 495 tonnes of longfin eels each year.

“It’s a very sustainable and well-managed industry,” argues Vic Thompson as we walk amongst several holding tanks full of writhing eels. Having fished both longfins and shortfins commercially for over 40 years, Thompson now owns Mossburn Enterprises near Invercargill, one of two eel-processing plants in New Zealand. He agrees that fishing has not always followed a code of best practice.

“In the 1990s, it became increasingly clear that the commercial fishery needed to be properly managed,” he tells me. Through his position as chairman of the South Island Eel Industry Association, he has helped to draw up the guidelines that now govern the fishery. “Since we implemented the quota system in 2000, not only has there been a significant drop in the number of people fishing, but the harvest is conducted in a much more rotational way.” In addition, all females that exceed the upper size limit of four kilograms are returned to the water. “As commercial fishermen, we take the rap from people about the eels disappearing,” says Thompson, “but the problem lies with farmers and developers who destroy eel habitat.”

But others are not convinced. “Would you kill a kiwi for $4?” asks Massey University freshwater ecologist Mike Joy. “That’s how much one of our endemic longfin eels is worth on the export market, despite the fact that it has the same vulnerability status as the great spotted kiwi.”

Joy and a group of like-minded individuals have recently called for a moratorium on commercial eel fishing. They argue that the fishery provides too few returns to too few people to justify continuing.

“Just look at America, Europe, Japan,” says Joy. “Their eels are now on the brink of extinction, and in large part that’s due to habitat degradation and overfishing.”

Modelling of our own eels has shown that if just five per cent (a very conservative figure) of the longfin population is fished, recruitment could drop by 83 per cent. In other words, killing a small percentage of eels now will mean a huge reduction in eel numbers in the not-too-distant future. Don Jellyman agrees that longfins need to be managed conservatively. “The consequences of what we’re doing now may not become clear for many years. When we do start seeing a drastic decline, it might be too late.”

So what does the future hold for our endemic longfin eels? Can the public learn to love our mysterious monsters of the deep? For a documentary, I recently auditioned a group of 10-year-old girls for a part that required the successful starlet to be in close proximity to eels. When I quizzed my pick of the bunch whether she was scared of the creatures, she vehemently shook her head. “I fed a big eel at Willowbank Wildlife Park,” she told me with a shy smile, “and I thought it was lovely.”