Tainted Games

For 10 years, from 1975 to 1985, sport and politics collided in New Zealand, and as with this year’s Beijing Olympics, political agendas, national pride and people’s lives were on the line. In 1976, the eyes of the world were on the 21st Olympic Games: an opening ceremony in Montreal’s Olympic Stadium was marred by the withdrawal of 24 African nations, a figure that grew to 28 during the games, in protest against the All Blacks tour of apartheid South Africa. Five years later the Springboks were to tour New Zealand, an event that led to social division and civil disobedience on a scale never seen before or since in this country.

The opening ceremony of the Montreal Olympics was televised live in New Zealand from 7 am on Sunday, July 18, 1976, and those New Zealanders who rose early to watch turned on their set with some trepidation.

The national teams marched through and symphonic music sounded across a stadium crammed with 75,000 people. Then came the ringing vowels of Queen Elizabeth in her Hardy Amies pink suit and hat, declaring open the 21st Olympiad of the modern era. Two young athletes, one French and one English—to reflect a bicultural Canadian nation—entered the stadium and together ran the Olympic torch around the track. The two runners then moved to the grassed centre of the stadium. They mounted the podium and dipped the torch into the giant saucer that would keep the Olympic flame alive for the duration of the games.

The flame rippled metres-wide across its new vessel, the cameras pulled back, and that was when you saw it. The world’s teams were gathered upon that oval, but there was green space everywhere. In this hour of Canada’s glory, no commentator was going to name the 24 national teams who had already decided to boycott the games, and the four about to join them. But as a New Zealander, you already knew. You registered the green spaces at the centre of the oval, and it made you suck in your breath. New Zealand was there, but in protest at the All Blacks tour of South Africa, nearly all the African nations weren’t.

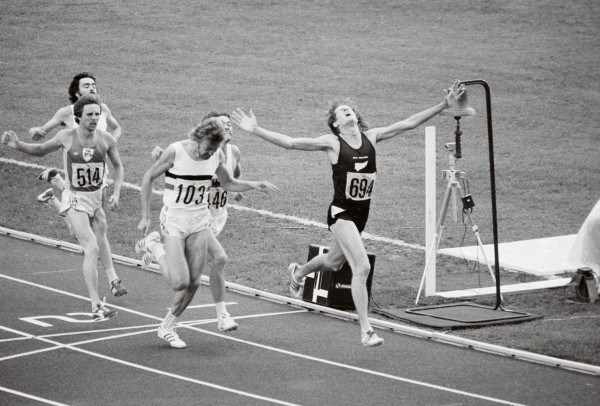

New Zealand won two gold medals at the 1976 Montreal Olympics—John Walker won the 1500 m, and the New Zealand men’s hockey team beat Australia in the final, 1-0. Two golds, but if the five Olympic rings represent the world’s five continents, a ring was missing: Africa’s. As a result, New Zealand’s international reputation—for multi-racial tolerance, for fairness, for leading the world in many of the most vexed social issues—suffered a grievous blow.

[Chapter-Break]

The very regal, very historic Marlborough House in Pall Mall is the Commonwealth headquarters and it is here, nine months later in April 1977, that the world’s most intractable sporting problem is about to land.

After intense diplomatic traffic that has not included New Zealand, diplomats of what’s called the “old Commonwealth” have pushed the problem onto the secretary-general of the Commonwealth, Sonny Ramphal.

Ramphal knows the problem well. He has been to New Zealand himself, and noted the tucked-up cheek, the great wagging head of determination. No, the New Zealand Prime Minister, Robert Muldoon, will not interfere with the rights of his country’s sporting organisations to visit, or be visited by, the sports teams of their choice. And that includes South Africa.

It doesn’t matter that the United Nations General Assembly itself has unanimously supported the call to boycott all apartheid sport. It apparently does not matter that the high-profile All Blacks have broken that boycott by touring South Africa while the greatest death toll since the Sharpeville shootings was still building. While Soweto was still burning. While the corpses of the shot children were still warm.

And now the African Commonwealth countries, which boycotted the Montreal Olympics because of New Zealand’s presence, are threatening to extend their boycott to the Edmonton Commonwealth Games of 1978. The pressure is on to do something about it.

Ramphal passes the problem on. New Zealand lawyer Jeremy Pope looks up from his desk in the converted servants quarters at Marlborough House as Ramphal’s personal assistant pokes his head around the door.

“The boss says you’re to do something for CHOGM to fix the problem.” CHOGM is the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting, just six weeks away.

“Well, what exactly am I supposed to do?” asks Pope. The PA grins. “The only advice I can give you is to pass on what the boss just said to me. ‘Jeremy’s bastard got us into this, so Jeremy can get us out of it.’”

Pope, well-known in New Zealand at that time as the former editor of the New Zealand Law Journal and co-author with wife Diana Pope of the best-selling Mobil Guide to New Zealand, is newly employed within the Commonwealth secretariat as assistant director of its legal division. He begins to draft a statement on apartheid in sport, aimed at closing the gap between New Zealand and the rest of the Commonwealth nations. It will bring together two areas of life the New Zealand Government has been at pains to set apart—sport and politics.

One of the Greek myths, current when the Olympics were staged at Olympia and still boasted chariot races and laurel wreaths, had the god Hercules drawing together those two rocky pillars at the entrance to the Mediterranean, to keep out the fearsome creatures of the ocean beyond. As Pope sets about his task of drawing together sport and politics, there are plenty of incentives to get it right.

[Chapter-Break]

The document worked on at Marlborough House be‑came the Gleneagles Agreement of June 12, 1977. On that day, at the Commonwealth Heads of Government retreat in Scotland, Muldoon, along with other leaders accepted “the urgent duty of my Government to vigorously combat apartheid by taking every practical step to discourage contact with South African sports teams…”

The next big New Zealand sporting contact with South Africa was the Springbok tour of July-September 1981. That tour had been on the international schedule for years but needed a formal New Zealand Rugby Football Union (NZRFU) invitation.

[sidebar-1]

Deputy Prime Minister Brian Talboys wrote a letter to the NZRFU in April 1980, emphasising the responsibilities of sports bodies and governments under the Gleneagles Agreement. But why did the Deputy Prime Minister rather than the Prime Minister himself deliver this heads-up about responsibility? Why did the Talboys’ letter say “I am deeply concerned”, rather than, “The Government is deeply concerned”? The NZRFU was on full alert for every sign, every inflection. In September 1980, it issued the invitation.

History already showed a prime minister could stop an incoming Springbok tour. The Labour Prime Minister Norman Kirk had done exactly that in 1973. Kirk had asked—the word used in his final letter to the NZRFU was “required”—the union to defer the Springbok tour of that year, and the NZRFU had done so.

Even Muldoon had shown a willingness to mix politics and sport. In 1980 he’d met the New Zealand Olympic and Commonwealth Games Association and hinted at the removal of financial grants if it did not support an American-led boycott of the 1980 Moscow Olympic Games. The association complied.

No such tough stances had yet been visited on the NZRFU, but the Springbok tour was still months away, so the nation waited. The more experienced anti-apartheid heads operating out of Wellington wanted the issue to move along quietly, using international pressure, the Gleneagles Agreement and polls that had shown public opinion was trending against the tour. They didn’t want threats or civil disruption, but on that point there was a tactical split in the movement. Aucklanders John Minto and Dick Cuthbert were already workshopping civil disobedience classes, offering lessons in arms-linking and in passive dropping, and active training for parachute jumps using aircraft.

[Chapter-Break]

The first big mobilisation against the Springbok tour of 1981 brought an estimated 65,000 people onto the streets of New Zealand’s major cities. By the time of the second big mobilisation of June 3, the polls were running 32 per cent for and 51 per cent against the tour.

The Prime Minister scheduled what was to be his first and last direct appeal to the NZRFU, to be televised live on July 6, 1981. The country tuned in. Most people expected a strong call to the NZRFU, but they reckoned without Muldoon’s stubbornness on the issue of sport and politics, and the importance to National of securing rugby-mad provincial seats for the November 1981 election.

The Prime Minster’s speech that night was best described as odd. It recalled the bond between South Africa and New Zealand—how the soldiers of each had fought and died together in WWII—and drifted on to its limp conclusion: “I say to them [the NZRFU], think well before you make a decision.”

Having waited for months, many New Zealanders felt betrayed. Not by the NZRFU (its position was always clear) but by the Government, which had lost its footing on a basic issue of integrity—or so it seemed. It had lost footing internationally at Gleneagles, and internally with its choice to step back from fundamentally opposed forces within society.

The Prime Minister had long ago targeted the New Zealand anti-apartheid movement as a brittle enemy. That bias in the movement towards the intellect, towards morality, towards the idealism of the political left, didn’t seem to compare with the emotional power of rugby and the pro-tour love of sport.

[Sidebar-2]

But the anti-tour demands were now emotional too. From the distress that had built during the Soweto shootings of 1976. From patriotic pride wounded by the events of Montreal that same year, and the insults to African leaders before and since. From indignation, that the hard-fought Gleneagles Agreement had been, apparently, slyly discarded.

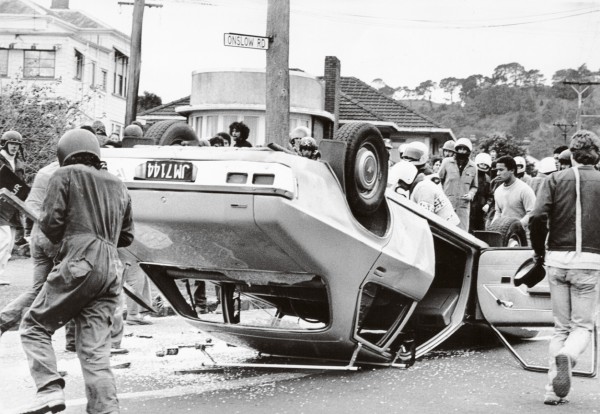

As the Springbok tourists arrived, emotions ran high throughout the country, among those both for and against the tour, and so high that the unspoken social contract that kept citizens generally at peace with one another fractured.

[Chapter-Break]

July 25,1981. The protest group is huddled mid‑ field on Rugby Park, Hamilton, the second fixture of the Springbok tour. Red smoke drifts up from flares and the green field is cut into geometric lines by police in glinting riot gear. Around the protest group, in the terraces and the stand, on slopes that look as though they might avalanche, are 18,000 rugby fans.

Radio news puts out a continuous commentary: “More police are coming out from under the stand. They’re equipped in their riot helmets. The visors on the helmet. Long batons slung at their hips. They’re moving in towards the demonstrators in a line.”

Then television, primed to begin broadcast of the Springboks’ provincial match against Waikato, begins transmitting that smoky image of the entrenched group on the field. People vault suburban fences to tell their neighbours. Soon the nation is watching. Those who support the tour are repulsed into rage. Those who oppose it see, at last, a potent symbol of their dissent.

On-field the group is facing outwards and packed tightly for its own survival. There is the euphoric fulfilment of the chant when some genius leads a change from the reedy ANC freedom call, “Amandla!” to the full-throated Kiwi call, “The Whole World’s Watching!” Well exactly. At 4 am in South Africa, something like half a million whites have awoken to the first live television coverage of the first Springbok rugby game abroad since the country was networked in 1976. All they see is a graphic display of the New Zealand anti-apartheid movement.

Communal energy infuses the on-field group. This high-profile Springboks v Waikato game is severely at risk. If police charge, the on-field group looks sufficiently resolute to go down as a bloody fullstop to the tour. If the police prise people out of its linked-arms mass, as they’re now doing, the clearance will take hours.

There’s also a stolen plane on its way to the rugby ground, piloted by the ex-fighter pilot Pat McQuarrie. Pat is staunch. He could also be mad enough. No one knows what Pat might do.

The game was called off by Police Commissioner, Bob Walton, in the interests of public safety the situation deteriorated. The picture that perhaps best represented what happened at Hamilton that day was one that was snapped off a television screen news bulletin. It’s a fuzzy, murky image, but its very lack of clarity encompassed all the distortion and indecision, the fear, the defiance. The pelting as the protest group filed out of the ground, the hunting through the Hamilton streets, the violation of the sanctity of Red Cross ambulances and, as night came, the besieging and ransacking of houses. The mob.

[Chapter-Break]

The rugby park cancellation had taken place on a Saturday. Government ministers met the next day,with police, and decided the tour issue—whether to play with an apartheid team—had changed to one of law and order. The police had failed at Hamilton, and would be given more support to protect the rugby grounds, starting at Palmerston North.

Backed by Army engineers, the police would now establish secure perimeters out from the rugby grounds, with narrow entrances manned by trained units. Four days after Hamilton, the new policies were already apparent as a quivering Red Squad line stopped the protest march 200 m out from the Palmerston North park, and later that day knee-charged an errant group of 100 who’d got too close to the ground, with the first use of the chant, “Move! Move! Move!”

Even when composed of apparently friendly bobbies, police lines could no longer be pushed around. In Wellington, protestors at a mid-week march failed to heed police warnings, and as they pushed into a police line on Moles-worth Street, were heavily batoned.

Police strategies had changed, and protest strategies changed in response. With spies all around, the movement spun off into tight and loyal action groups that in the weeks ahead would cut cables on the television transmitters above Christchurch and Waiatarua in Auckland, as well as the relays south of Timaru and above Dunedin. They would drop the flagstaff at Waitangi, halt Wellington rail with an early morning gelignite bomb, detonate a big helium balloon over Lancaster Park and hack through the conductor cables at Auckland’s Moirs Hill microwave relay.

The big coalitions in every city encouraged their troops to wear hard hats and carry defensive shields. The strategy was to stretch police resources countrywide. The coalitions’ marshals planned the big set-piece actions that blocked airports and highways and bridges, and twice a week, coinciding with every Springbok game, rolled onto police blockades, exchanging insults and trading blows with rugby followers off to see the game.

Something like 150,000 people turned out on the streets during the three-month tour, the biggest mass protest New Zealand had ever seen. And while some of the action was grim, the carnival kept rolling, and its numbers kept growing, partly because it was also such fun. In the spirit of the Robert Crumb dictum of the 70s—“Remember kids to keep a smile on yer face when yer smashing the State”—the protest people tried to run Christchurch dry of water with the Tap Campaign, or pulled off brilliant stunts like the bogus referee who kicked the ball high into the stands at the start of the Auckland game.

[Chapter-Break]

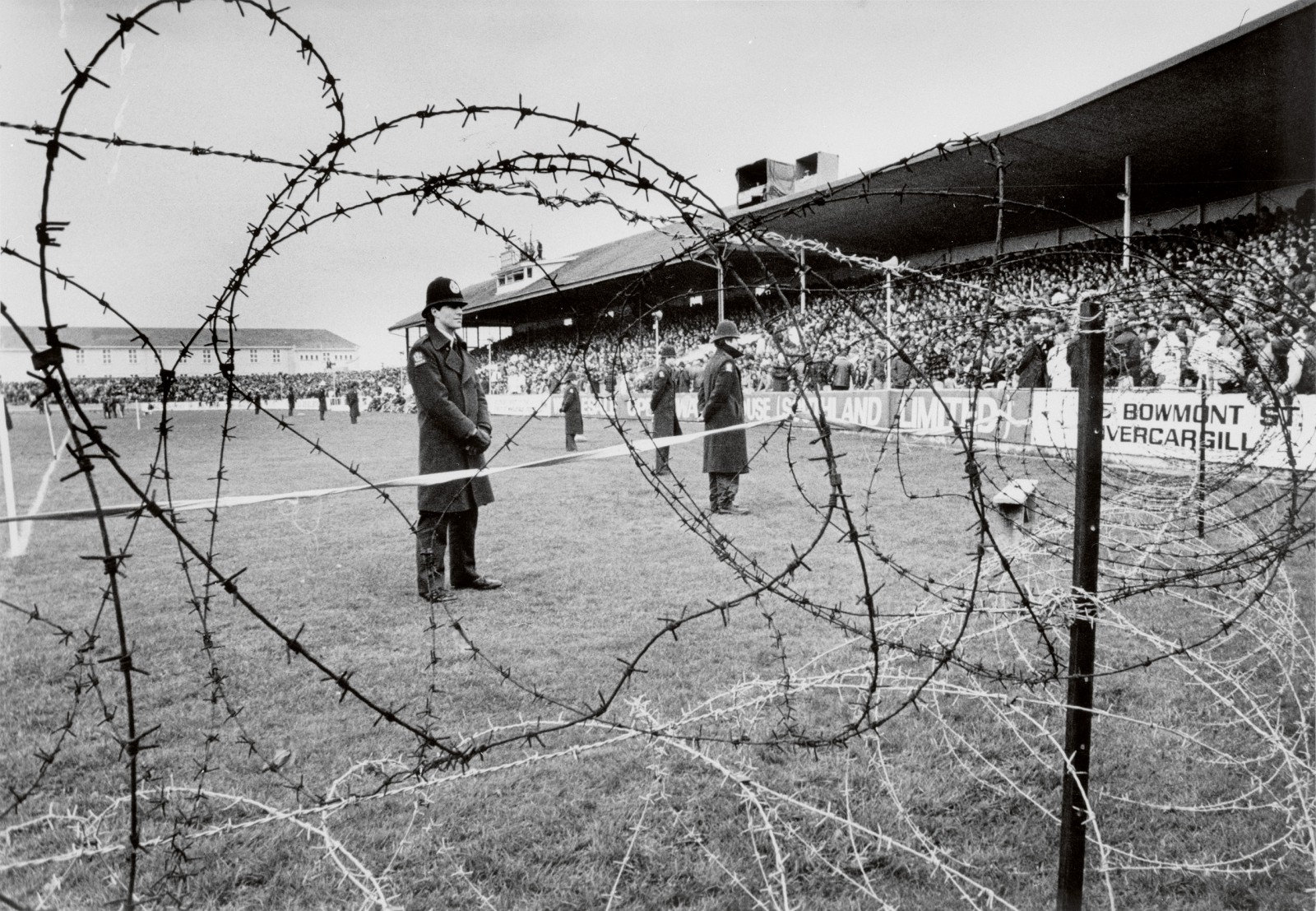

But the dissolution of the normal social constraints turned dangerous on the last and most sinister day of the tour: the third test, Eden Park, September 12. Eden Park was the most heavily fortified venue of the tour, with the main perimeter now pushed out to 400 m, reinforced by bins and shipping containers, and with an inner defensive circle just 200 m out. The Army laid its barbed wire in zig-zag formations outside the park to counter grapnels, and in coils on the field itself to stop whoever might come over the barriers and seek to run onto the field. Some police now had shields, and the PR24 long baton squads had doubled from two to four, with military anti-riot squads standing by as needed.

Around the city that day the disruptions, such as blocking the Auckland Harbour Bridge with cars and chains, had become almost normal. People waited to see what the day’s stunts would bring—such as the release of enormous hydrogen balloons over Eden Park.

The foot-soldiers gathering at Fowlds Park were triaged into three squads: Biko, Tutu and Patu. The latter squad was tipped to take direct action. Its front lines donned ice hockey masks and chest armour, for protection against batons. As the squads began their probes around the Eden Park perimeter to loud-hailer cries, their sounds were soon accompanied by the clatter of batons on helmets and shields of any squad that had pushed onto police lines. By then that was expected, but there was also the wild card. Coming up to 2 pm, half an hour before the start of the third test, Marx Jones, a tanker driver, and Grant Cole, a railway worker, taxied to the end of a Dairy Flat runway in a hired Cessna dubbed Dixie, for the DX capitals in its registration code. They jumped out, quickly loaded the little plane with pamphlets, flour, paper bags, metre-square plastic and netting sections, then took off. With Mt Eden within sight, Jones radioed to Auckland Information, the 24-hour call station for light aircraft.

“This is Radio Anti-Apartheid. Please inform the police and the rugby union they’ve got just 10 minutes to stop the third test.” There was a long silence before the call station came back.“Or what?”

The third test got under way, and Patu was psyching itself up in front of the police block at the corner of Walters Road and Marlborough Street, thrumming its shields and beating the bins with its fists.

“Hooh! Hooh! Hooh!” The Red Squad line there stamped forward three paces, jabbing with their batons, and the police megaphone barked a warning. Those who’d volunteered for Patu felt a chill of fear for what lay ahead.

Patu pulled back 40 m to plan its move, and at 2.40 pm, an armoured front line backed by more than 100 street warriors charged, tilting its shields into the jolting horizontal as it closed on the police line on Walters Road. The charge put some police on the ground, but the line held, and then the intersection became the scene of turmoil. Smoke poured from a phosphorous bomb beside a corner church, sky rockets zoomed out of protest ranks straight at police lines, who now also had to dodge the hail of stones, cans and palings that had been wrenched off fences.

The Red Squad held the line but a reserve Black Squad unit suddenly struck its way out from the middle of that line in a counterattack that split the shielded protest front line and began to chew into the mass behind. Red Squad police swept into the intersection in support of the baton charge and when it was over, six or seven groaning or unconscious people lay on the ground and a medic was trying to fit someone’s teeth back into gaping sockets. Police supported one of their own inspectors, reeling from a blow to the head, and escorted back to safety a Red Squad man, isolated from his group and chopped on his shoulders and back by shields, his damaged arms dangling.

And then everyone pulled back, the intersection remained strangely empty, police and protestors alike treading around the edges of an intersection marked like a place of magic with splashes of blood, rocks, shields and the bright colours of abandoned helmets.

Above and beyond all of it, Dixie made its 50th pass across the ground, then headed back to Dairy Flat, leaving Eden Park splashed with flour bombs and litter. A police tail of two helicopters and a fixed-wing aircraft swung in behind it.

Concerted police baton drives against protest squads injured many people that afternoon. When the protest finally wrapped up, the medics calculated 270 people had been hurt, some badly—like the two clown protesters, along with their mate the bumble bee, far from the action but batoned by three seemingly out-of-control Red Squad men. Thirty-two police required treatment.

The dispersing protest streamed back towards Auckland, and the last chant was “Muldoon Must Go!”

[sidebar-3]

The Muldoon Government was re-elected in November that year on a no-change sports policy, but was living on borrowed time with a single-seat majority and a rebellious MP, Marilyn Waring. The country was about to switch allegiance to the Lange Government which, when it came to power in 1984, changed many of the Muldoon Government’s policies, and closed the South African embassy. The anti-nuclear and antiapartheid policies of the Lange Government enacted much of what the student generation of the 60s, 70s and early 80s had fought for.

Well, almost. In 1985, the NZRFU announced the All Blacks tour of South Africa would take place as scheduled. Prime Minister Lange spoke sternly on the subject,but his Government could do little. It could stop an incoming South African tour by withholding visas, but wouldn’t prevent its own citizens travelling abroad. The NZRFU’s proposed tour was stopped in the end, not by government decree, nor by protest action, but by the issue of an interim injunction—it was stopped by the law.

[Chapter-Break]

And that, after a turbulent decade, was perhaps the end of the idea that sport might always and forever float free of politics, an ending that was strangely reinforced in November 2006 at the International Rugby Board headquarters in Dublin.

At issue there was a decision on the next host country of the 2011 Rugby World Cup, and in a three-way race, New Zealand was given only a small chance of success against South Africa and Japan. The first secret ballot eliminated South Africa, which was then free to place its two votes for either Japan or New Zealand.

Before the second ballot, South Africa’s Sports Minister, Arnold Stofile, gave a surprising interview. In the turbulent years before the ANC became South Africa’s governing party, Stofile had visited New Zealand to gain support for the ANC’s sports boycott. He made good friends here, and was jailed on his return home by South Africa’s Botha Government. In his Dublin interview, Stofile declared South Africa would vote for New Zealand in the second ballot, and by so doing would acknowledge the past: “Part of our vote is for…the people of New Zealand who helped us.”

Keith Quinn (on a TV One blog) was the only New Zealand commentator who reported this. “The way I saw it,” he wrote, “Mr Stofile was publicly thanking Messrs John Minto and Trevor Richards and the rest of the New Zealand protest people for their role in changing rugby and life in South Africa 25 years ago.”

A few days later, the South African President, Thabo Mbeki, confirmed it in the Government magazine ANC Today: “…we must mention the outstanding role played by the people of New Zealand in the campaign to isolate apartheid sport as we engaged in struggle for our liberation,” he wrote. “If only for this reason, it was good that SARU (the South African Rugby Union) supported the New Zealand bid.”

The voting figures were secret, but leaked minutes from the Argentina Rugby Union’s general committee in January last year suggested the final vote was a close-run 11-10. If that is correct, South Africa’s two votes were critical for New Zealand’s success in gaining the 2011 hosting rights. With that, the high-intensity battle that began in 1975 to keep politics out of sport had come full circle. Three decades later, the political protests of 1981 had finally delivered New Zealand the sporting event dearest to its heart.