Star struck

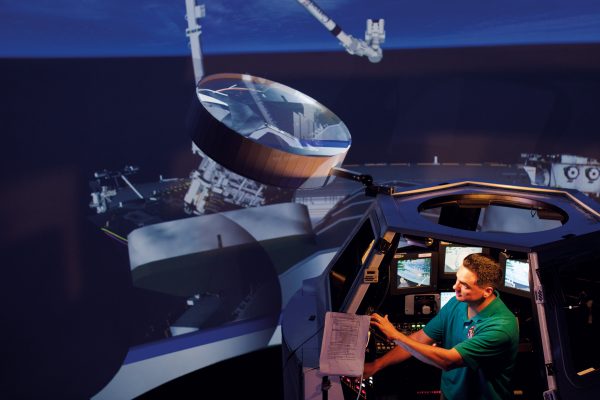

Aerospace engineer Mana Vautier helps ensure the International Space Station runs smoothly. One day, he hopes to step aboard.

Like many children, Mana Vautier was captivated by space travel early on.

“As far back as I can remember I was very interested in space—in particular, human space flight,” he says. “I’ve always looked up at the night sky and loved what I’ve seen.”

Usually, such childhood fascination wanes—especially considering that the steps between dreaming of visiting space and becoming an astronaut are so numerous that ‘rocket science’ has become an analogy for ‘the hardest job in the world’.

But Vautier is still on track for the final frontier. Based in Houston, Texas, the father of five works at NASA’s Johnson Space Center on the upkeep of the International Space Station (ISS).

“There are a lot of different subsystems required to keep it flying safely,” he says. “You’ve got electrical systems, propulsion systems, environmental control systems, life support systems…”

Vautier’s role is to ensure that “everybody plays nicely together”, he says. “It’s a national laboratory, so there are a lot of scientific experiments and payloads on board.”

Vautier was born in Lynfield, Auckland, though his family has whakapapa ties to Rotorua, and he’s of Te Arawa (Tūhourangi) and Ngāti Kahungunu descent. When he was four, his father was posted as an aircraft engineer to Hong Kong, and the whole family relocated there. Vautier’s education—and career—has been international ever since, although he has kept his links to home throughout. His American-born children all have Māori middle names, and have inherited their father’s love of rugby—and undying support for the All Blacks.

“It’s very important to me to keep my ties to New Zealand strong, from a family perspective and also from a cultural identity perspective,” he says.

He returned to Auckland for high school, and after a year at the University of Auckland, moved to the United States to study—a degree in physics and astronomy from Brigham Young in Utah, then postgraduate work in aerospace engineering at Auburn University in Alabama. While at Auburn, he gained a summer internship with Odyssey Space Research, a small company based at the Johnson Space Center. It was Vautier’s first step into the hallowed halls

sof NASA.

“I don’t know if the first-day high ever really disappeared,” he says, laughing. “I was doing research exploring spheres of influence of the gravity of the Earth—where that sphere of influence ends and the sphere of influence of the gravity of the moon takes over.”

That research became part of his masters thesis on translunar trajectories, and after he graduated in 2008, there was a job at Odyssey waiting for him, creating computer simulations to model different aspects of space flight.

“There are two main approaches to designing things. You’ve got the ‘Just build it and then test the hardware’ approach. If you don’t build it very well or if the design isn’t very good, then you might end up spending a lot of money on hardware.”

Alternatively, he says, there’s what he calls the “Model and simulate as much as possible” approach. “You can use computer simulations to model the physics of how the hardware is going to work. If you have really good models and simulations, you can potentially save a lot of money. Where space flight is involved, it’s really expensive to get mass objects into orbit.”

In 2012, Vautier moved to his current role working with subsystems integration on the ISS. Collaborating with people from the ISS’s partner countries—the United States, Russia, Japan, Canada—and the European Space Agency is something he particularly enjoys. Currently, that involves planning how Russian-built modules can be added to the ISS, and ensuring that commercial spacecraft can dock there.

“It’s really a neat, international, collaborative effort.”

Vautier hasn’t lost sight of his first love—human space flight. At present, that involves enabling others through his work on the ISS, but he’s determined that one day he’ll step aboard.

So far, NASA has put only one Kiwi into space—Harold the Giraffe, the mascot of the Life Education Trust, which was taken to the ISS by astronaut Nicole Stott on NASA’s Mission STS-128 in 2009 as part of a campaign to encourage children to talk about their aspirations.

Becoming an astronaut is an 18-month selection process, followed by two years of preparation, which includes learning Russian, public speaking, survival training and medical training, on top of the advanced scientific qualifications that candidates possess.

Vautier is already an all-rounder, with an extensive resumé of extracurricular activities. He’s a member of Engineers Without Borders, a long-distance runner and volunteer firefighter, the director of a charity fun-run, a fire-department vice-president, and the Houston manager of a non-profit organisation that repairs homes for the elderly at no cost.

All that—and he discovered in May that he hadn’t been selected for the 2017 astronaut intake.

“It was a little disheartening to not make the cut, but I’ll try again next time,” he says. “Typically, early 40s is about the oldest an astronaut is at selection, so I figure I have one more attempt. I’d like to get some more remote experience under my belt, like an expedition to Antarctica.”

Whether or not he makes it aboard the ISS, Vautier is still encouraging a new generation of young scientists to shoot for the stars. In January, he returned to New Zealand to launch Pūhoro, a science, technology, engineering and mathematics academy for Māori high-school students, founded by a Massey University associate director, Naomi Manu.

Vautier is now an ambassador to the 80 or so students, and he Skypes them regularly. He says there are “big ideas” on the table.

“One of the major setbacks for some kids is the preconceived idea that there were only certain paths they could take,” he says. “Pūhoro allows students to really open their eyes and see that’s not the case.”