Shadow of a Giant

It was Hillary’s long-time friend Jim Wilson, a student of Eastern religion and culture, who wrote: “Life gives and takes in a way indifferent to individual human desires. Wisdom consists in realising that it cannot be otherwise; enjoying when it gives and enduring when it takes”.

The words appeared in From the Ocean to the Sky, Hillary’s account of his 1977 jet boat expedition from the Bay of Bengal 2575 km up the Ganges river to its source in the Himalayas. Two years earlier Hillary had been grief-stricken by the deaths of his wife Louise and youngest daughter Belinda in an air crash in Nepal. He found himself forced to endure when life had taken, and it hit him hard. The journey up India’s sacred river with his son Peter and a handful of old climbing mates started out as yet another adventure. But it soon became something different—a spiritual pilgrimage.

The growing sense of profundity was accentuated by the thousands who gathered to see Hillary at every stage of the trip. He embodied the spirit of adventure—one widely used Indian school textbook of the day devoted an entire chapter to the conquest of Everest. More than that, through his river pilgrimage he symbolised to devout Hindus the greatness, the potential divinity even, of all humanity. Although not a deeply religious man, Hillary in turn found aspects of Hindu faith and worship deeply moving.

Gradually he relaxed into Indian culture, charmed by its exuberance and energy, and took to wearing beads—a gift from his son—and local wrap-around clothing. Eight years later, he was to renew his contact with the subcontinent when he was appointed high commissioner to India and New Zealand’s representative in Bangladesh and Nepal, posts he held for four and a half years.

There is a telling anecdote from the Ganges trip. One day at Mirzapur, Hillary’s party were met by a 68-year-old yogi who claimed to be able to arrest the beating of his own heart, to bend iron spears with his eyes and to stop cars in their tracks. After giving the New Zealanders a convincing taste of his powers, he challenged one of the jet boats to a trial of strength. The next day, watched by an eager crowd, the yogi hammered iron stakes in the ground and laid a railway sleeper against them. Bracing his feet against the heavy timber he took the strain of a rope fastened at the other end to the distant jet boat. The slack went out of the rope and, as the engine noise rose, the muscles on the yogi’s legs began to quiver and shake, his face showing that he was using all his powers. The noise reached a crescendo, but still the yogi held his ground. Then a shout went up, the engine was cut and the yogi leapt to his feet with delight.

“We shook hands and congratulated him, as pleased as he was,” wrote Hillary. “For although I was impressed by his strength, it was the courage of the man that I admired above all else.”

Then, as always, it was the inner qualities that mattered.

From almost the moment Hillary first set foot in the Himalayas the recognition of something similar had drawn him to the Sherpas, with whom he was to forge a lasting bond.

“Few of us had failed to learn something from the character and temperament of the men themselves, their hardiness and their cheerfulness; their vigour and loyalty; and their freedom from our civilised curse of self-pity,” he wrote.

It was during a stay in the Himalayas in 1960, this time to investigate the physiological effects of high altitude on human performance, that Hillary’s admiration for the Sherpas found a practical expression. Along with other climbers, he had been flown in for a prolonged stay at 5800 m in what was dubbed the “Silver Hut” to be scrutinised by science. Sitting with Sherpa friends around a smoky fire one day, in a barren stretch of country near the Tolam Bau glacier, he asked what they felt would most help their village. Farm improvements? A medical clinic? The answer was unequivocal: education.

The team eventually concluded that the yeti was a mythological creature, probably

based on sightings of the Tibetan blue bear.

The next year, with financial support from the expedition sponsor, Hillary returned with friends and a quantity of aluminium to put together the region’s first development project, a schoolhouse in Khumjung. Surrounding villages liked what they saw and petitioned the hero of Everest for similar help. More money was found, a formidable contingent of porters hired and Hillary’s Schoolhouse Expedition of 1963 brought its weight to bear on the hills and valleys of the Sherpas.

The next year he set up a charitable foundation, the Himalayan Trust, to fundraise and manage projects in Nepal. To date the trust has build some 30 schools and has had an impact on twice that number. But Hillary’s attention wasn’t limited to the classroom. In later years he repeatedly returned to establish clinics and hospitals, lay water pipes and throw bridges across wild river gorges.

These were far from paternalistic gestures imposed by overseas meddlers. The help he offered was that of a friend, not of an institutional machine. Hillary used his ears before his hands. And he was careful to avoid sowing the seeds of obligation. Nor did he attempt to create some ersatz western dream in those remote mountain valleys. The assistance did its best to leave culture, faith and traditional values intact.

“The Sherpas’ finest traits have been developed in their battle against their tough environment,” Hillary once said. “The last thing I would wish to do is to remove them from battle completely; better to put some sharper weapons into the Sherpas’ hands.”

It almost backfired. When Hillary built an airstrip at the village of Lukla, a once-isolated gateway to the Sherpa homeland, he brought the world to their doorstep—the market town of Namche Bazar, the main Sherpa settlement, was just two days’ walk further on. Hillary had created the airstrip—a mere tilting scrap of cleared ground high in the mountains—to land supplies for his building programme. But for years he fretted at the increasing tourist numbers it encouraged.

Hillary needn’t have worried. The Sherpas soon learned to survive—to thrive, even—amid the higher traffic count. And the invigorated trekking industry, though it put a strain on village infrastructures and on the environment, also brought relative wealth to the region, insulating it from the grinding poverty and political neglect that continues to beset Nepal’s western provinces.

[Chapter break]

When I went to the Himalayas some years ago to witness Hillary’s legacy in Nepal at first hand the warmth of feeling toward the man they called Burra Sahib (“big in heart”) was everywhere apparent, as was the physical imprint of his work. Soon after setting out from Lukla on one of the narrow, winding foot trails that serve as roads, I came across a modest building at Mahendrajyoti school which bore the sign: “Sir Admund Hillari Block A, 1965”. A nearby inscription marked the addition of Block C, some 20 years later. Further on, within sight of the boulder-strewn Dudh Kosi, stood the buildings of Chaurikharka, another school supported by Hillary’s trust.

The pattern repeats throughout the valleys and hillsides of the region. Even the 1200 sq km Sagarmatha National Park, whose boundaries encompass Everest and the entire Sherpa region, owes something to Hillary. He lent his weight to plans for establishing the park, pushing the New Zealand government to provide financial backing and management expertise. The government obliged and the park, now a World Heritage Site, was gazetted in 1976.

The park’s mountain landscape is saturated with the expressions of Buddhism — from fluttering prayer flags and stone chortens to creaking water-driven prayer wheels and age-old walls incised with the devotional chant Om mani padme hum—”hail to the jewel of the lotus”.

The Buddhist faith had found a congenial home in Nepal after years of persecution in neighbouring Tibet by the Chinese, and Hillary did what he could to help keep the centuries old tradition alive. When Tengboche monastery burned to the ground in 1989, he and his second wife, June, spent four years raising the money to rebuild it. As the base camp for Hunt’s 1953 Everest expedition, the monastery held a special significance for Hillary, as it does to this day for all the climbers who go there to be blessed before tackling nearby Everest.

As the new millennium dawned, age and failing health increasingly put out of reach the mountains and the mountain people Hillary had known for half a century. The work of the trust went on, of course, and he continued to wear out a great deal of shoe leather on the fundraising circuit. But worsening bouts of the altitude sickness that had plagued Hillary for years put more and more of his old haunts off limits. Pulmonary edema almost killed him on 8470m-high Makalu in 1960, effectively ending his career as a high-altitude climber. The illness eventually affected even his humanitarian work, one bout forcing him to be airlifted down from Khumjung, the site of his first school, and hospitalised in Kathmandu.

“I will have to find ways of adjusting,” he told me as the constraints began to bite. He contemplated using oxygen and flying up into the mountains for brief visits. Or bringing his Sherpa friends down to Kathmandu. “I don’t want to lose contact with these good people. My life has been built around them”.

Despite the defiant words this was one battle Hillary was to lose. Eventually, even the relatively low altitude of Kathmandu offered no relief. Yet to the last Hillary drew satisfaction from his work in Nepal. It was, he often said, what he would like to be remembered for.

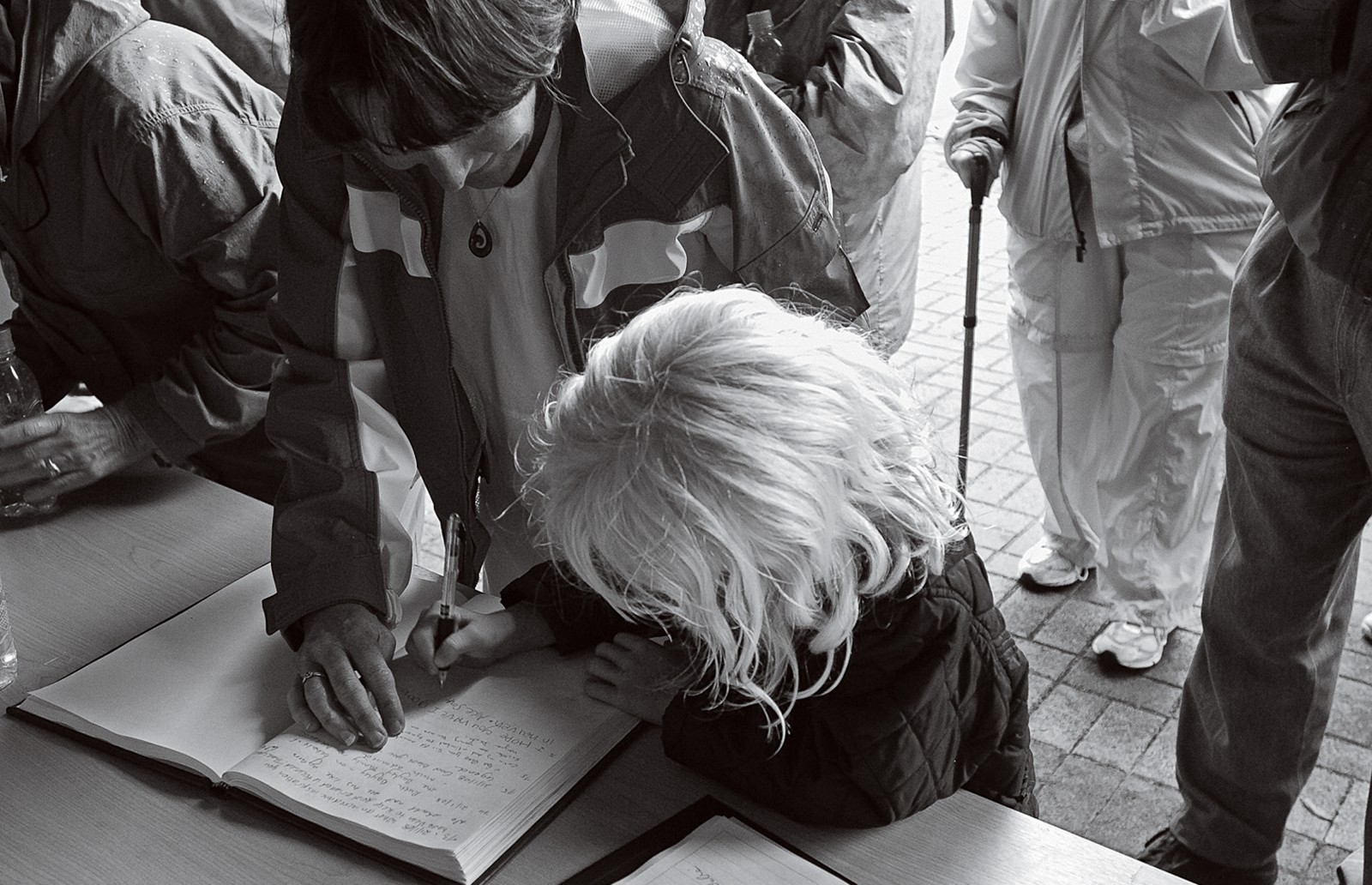

With fame comes the obligation to give something back, Hillary told me. Without question, his became a life of giving—whether to the Sherpa children of Nepal or the casual autograph hunter at the door. If the world lifted Hillary on high, he repaid the debt a hundredfold. And if the mark of a person’s worth lies not in the quantity or value of possessions but in the quality of his friendships then Hillary was rich beyond measure.

“For me, the most rewarding moments have not always been the great moments,” he once wrote. “For what can surpass a tear on your departure, joy on your return, and a trusting hand in yours.”