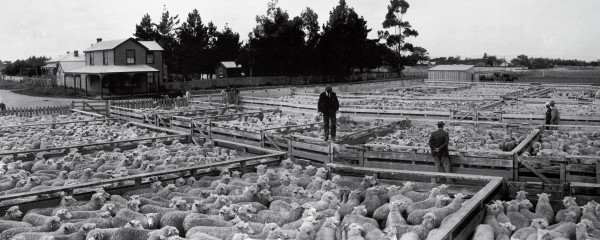

Saleyard

One corner of the town of Feilding is a vast expanse of sheep and cattle yards that fills up with livestock twice a week. And the locals wouldn’t have it any other way. The saleyards, which are among the largest in the Southern hemisphere and handle close to a million sheep and 100,000 cattle annually, have been central to the town’s existence and livestock farming in the lower North Island for well over a century.

In the pre-dawn chill of an August morning in Marton, Joseph Skou is firing up his truck in an industrial side road. While the truck warms up, Joseph tries to coax his young dog Jill from across the yard. Eventually he has to lead her by the collar into the metal box that hangs between the wheels of the trailer.

Out of the yard, Joseph chops through endless gears as the truck and trailer cross the Rangitikei plains and then climb cautiously along a narrow, winding road in the shadows. The truck rounds a bend and the Turakina valley suddenly materialises below, while Mt Ruapehu basks in the haze of first light in the distance.

Joseph’s stock truck is just one of dozens that will be trawling through hill country farms as far north as the mountain and delivering their cargo into the Feilding saleyards. More stock and buyers—will also be drawn from southern Taranaki and Wanganui to the west, East Coast, Hawke’s Bay and Wairarapa to the east and, on occasion, from as far south as Marlborough. During a South Island drought, the Feilding saleyards can reach even further south.

Joseph drives for his father Graeme’s company, and this morning he is picking up ewes with the first of the new season lambs tagging along from John Wigglesworth’s farm. On the way back he calls in at Ricky Swainson’s Marton farm to collect the tail end of last season’s lambs. Swainson also has a farm in Hunterville and usually sends stock straight to the freezing works, but occasionally has an excess of animals that may not be ready for slaughter that he sells through the saleyards.

When the trucks arrive at the saleyards, an organised chaos ensues. Farmers have booked their stock in with stock agents as late as the night before and the pens are allocated accordingly. Truck drivers holler to agents and yardies who then shepherd the countless mobs of cattle and sheep through the labyrinth of races and pens to their allotted enclosure. The bustle is still continuing right up to when farmers start arriving for the start of the auctioning at 11am.

[Chapter-Break]

Saleyards have been in Feilding almost as long as it has existed. In 1880 bush was still being cleared and burned around the emerging “town” of Feilding—little more than the Denbigh Hotel and a few modest dwellings and tents intersected by a couple of dirt tracks. For reasons no longer known, Jack Stevens and Colonel Gorton decided to round up some cattle and auction them in the stockyards next to the Denbigh. One hundred cattle were sold. On May 24, 1880, the stockyards next to the Denbigh became the Feilding Saleyards.

What started that day has become a regular ritual, unbroken for 125 years, a central part of the sheep and beef industry in the North Island, the cornerstone of the now substantial town of Feilding and a social focus for the far-flung rural community.

Today the yards may be bigger, but some of the posts in the older parts of the yards are little more than native tree logs that were dropped into holes.

At 11 a.m. on Friday morning a century and a quarter after the first sale, Dan Flanagan—a name that could easily belong to one of the first immigrants to arrive in the area—gets the sale underway with the first sheep pen at the far end of the yards.

With a voice booming above the bleating of lambs, the chatter of farmers, and the moan of the wind, Flanagan launches into his trade with a poetic flourish.

“Well good morning ladies and gentlemen, we are about to start and number one in the offering is from the property of Blackburn Farm, in from Ohakune, born and bred up in the mist and the clouds. There are 311 hulking, big brutal ram lambs indeed. Aren’t they monsters, ladies and gentlemen? A Waimarino ram lamb offering of three, one, one in number.

“Now their value is…well, I suggest something like the mid-seventies, take a four or five dollar bid for them, seventy-one or two. “Sixty five, sixty five, thank you Maurice, sixty six, sixty six…Sixty seven, eight dollar BID!! Eight dollar BID!! Sixty nine, Sixty nine…Can’t get them much better than these fellows. There must be seventy one dollars somewhere…We’ll take a little dollar, where—where? Seventy one, it’s seventy one. It’s all over, all done. One or two here Kerry? BID!! BID!! BID!! Seventy four… Seventy five fifty…Come on! Come on! Seventy five fifty…Are you in or out? All over, all done. Aren’t they beauts? Seventy five fifty, your call OK? Seventy, I’ll take it…Seventy six dollars didn’t work…BID!! Seventy six dollars twenty, I’ll wait! Seventy six dollars twenty, I’m going to sell them! Up they go! Seventy six dollars twenty. That’s the money, that’s the money ladies and gentlemen. Fifty-three the buyer. “All this is delivered with a rough musicality and flying flecks of spittle, wrapped in the conviction of an evangelist.

The farmers clustered around may or may not be interested in the pen under the auctioneer’s command. Some are just being nosy, or have come along to catch up on prices or chew the fat. The faces are weather-beaten, the hands leathery with fingers gnarled from physical work. The clientele—predominantly male—are clad in an assortment of woollen jerseys, check shirts, club rugby jerseys, bush shirts, and well-worn jackets bearing logos of drench companies. Most wear leather boots, usually caked in at least one layer of mud or manure. Many will follow the auctioneers around the sheep yards looking for a pen that takes their fancy. Others will head over to the cattle pavilion, plonk themselves on the wooden terraced seating and follow the prices for beef flashed nowadays onto large overhead displays as pens of cattle are automatically weighed and lots are sold. Or just have a yak and walk away with a bit of news to tell the wife, if she cares to listen.

The yards still occupy the site next to the Denbigh where it all started. The rhythms that it runs by were also laid down in the early days of its history. After the first sale, regular fortnightly sales followed and were later expanded to weekly sales with four firms involved—Gorton and Sons, Abraham and Williams, New Zealand Loan and Merchantile Agency, and Dalgety, Buckley and Co.

[Chapter-Break]

Sheep and cattle were farmed in earnest throughout Manawatu and Rangitikei from the 1840s onwards, starting on the flat coastal reaches and creeping up into the hills as bush was cleared and grass sown. Meat was for local consumption and improving the wool which brought in most of a farm’s income—was more of a breeding priority for sheep farmers.

The advent of refrigerated shipping quickly challenged this model. In 1882, 30,000 sheep carcasses were exported from New Zealand. The following year the figure jumped to 200,000. Ten years later, two million carcasses were frozen and shipped. This revolution took hold in the Manawatu in 1890 when a freezing works opened in Longburn, just south of Palmerston North. In the first season, more than 57,000 sheep were butchered.

Farming sheep for meat altered the pattern of farming. Hill country farms began to carry large flocks of breeding ewes, but the lambs they produced were grown, or finished, on easier country. The lambs born on the hills were sold at Feilding to finishing farmers, who eventually sold to the freezing works. Wool breeds, such as the merino, soon gave way to dual meat-and-wool breeds like the Romney.

By 1900 a pattern of stock movements had emerged, with sheep heading from the hill farms to nearby lowlands during the summer and autumn months and then to the freezing works a few months later.

By the 1890s, the Feilding saleyard was vying for stock with two yards in Palmerston North, but increasing urbanisation in that town forced the yards there to a less popular location, which led to their demise in the 1920s. In contrast, the Feilding saleyards grew in popularity. Their importance was established as early as 1902 when a North Island record of 45,000 sheep was yarded in one sale.

In 1916 the Feilding Farmers’ Freezing Company Ltd opened a meatworks on the east bank of the Oroua River just outside Feilding. Feilding was also becoming a centre for stud breeding and a ram fair was established at the saleyards in the early 1900s.

The rise of private cars and trucks after WWI meant people could travel longer distances to sales, accelerating the demise of smaller sale-yards and increasing the pre-eminence of the Feilding yards. Car travel also meant sale days became a family affair and a busy day for retailers and businesses in town.

Today the saleyards regularly turn over more than $1 million on a sale day and at the peak of the season from January through March yardings of more than 20,000 sheep and 1200 cattle are not unusual. The yards cover 3.7 ha with 350 sheep pens and 140 cattle pens, selling around 870,000 sheep a year and 90,000 cattle.

The influx of farmers and their cheque books is still crucial for the economy of Feilding. If the smell of thousands of sheep and cattle invades the middle of town, no one minds. It’s the sweet smell of cash to businesses and they know it. Not only banks and farm supply companies cluster around the saleyards. Cafés and pubs do a brisk trade on Fridays as farmers and their wives slake their thirst. The cafés and their well-heeled female clientele wouldn’t look out of place in Remuera or Ponsonby. Their four-wheel drives might though—many have actually got real mud on them.

At the end of the saleyards lies the Saleyards Café, colloquially known as the greasy spoon. The title “café” fails to do justice to the hodgepodge of formica tables and mismatched chairs that are crammed into a room where stock agents and farmers tuck into a menu of steak and chips, lamb shanks and burgers that, the waitress says, have “everything.”

She calls out a number for an order but no one hears her over the din. So she hollers at the top of her voice “78!!” There’s a momentary pause in proceedings. A quip from a ruddy-faced farmer in the waitress’s direction is met with a retort and a grin, which causes more mirth from the customers.

Happy farmers with money in their pockets means happy retailers and business people the economic mood of the saleyards is reflected in the town. And, eventually, the country as a whole.

[Chapter-Break]

While the auctioneering of a pen of 300 lambs may only take a couple of minutes, and involve little more than a tilt of an eyebrow to secure the purchase, a host of factors inform a farmer’s decision to buy more stock.

A purchase will be based on careful study of the farm accounts, possibly interest rates, the amount of grass available on the farm, the short and long-term weather forecasts since those stock will need to be fed for (many) months, the likely market price for the animals by the time the farmer reckons they will be ready to on-sell, (in turn, significantly dependent on future exchange rates, overseas demand and fickle local meat schedule prices) together with details about the animals themselves. What is the reputation of the seller’s stock, in what condition are their teeth and feet, how long since they have been shorn, what parasites might they be carrying, what is their growth potential, and will they be easy to move but not too wild? Memories are long. Buyers and sellers remember who got a hiding last time and reciprocate when the game is in their favour.

Things aren’t always entirely rational though. “Give a farmer some money and a lot of grass and things get silly,” remarks a truck driver.

The factors influencing the price of a lamb or steer are as large as the global economy. George Bush makes a bellicose utterance and the US dollar drops, pushing the New Zealand currency higher and hurting exporters of primary products. Meat producers are particularly vulnerable to such fluctuations, because the freezing works issue a new schedule of what they pay for different types of stock every week and foreign exchange fluctuations feed immediately into this.

News-readers on TV often say the dollar has made “good” gains. “Good” for who isn’t clear. At the saleyards a strong dollar and further gains aren’t good. Ironically, a strong agriculture sector may boost the New Zealand dollar, so lowering prices to farmers.

Meat companies set the schedule for lamb and beef depending on the availability of stock, how busy the works are, overseas demand and the exchange rate.

Prices can fluctuate by 10 to 20 cents a kilogram either way in any given season compared with the same month of the previous year. It doesn’t sound a lot—until you multiply it by 17 kg per lamb across hundreds or thousands of prime lambs.

Although European and American appetites for New Zealand protein are the major influences on prices paid in the saleyards, in the end nature is the boss.

The lower North Island is a giant farm, with livestock migrating from one area to another depending on the time of year, the weather and the availability of feed. A dry spell in Hawke’s Bay—not unusual—can mean sheep and cattle flood into Manawatu, but a couple of years ago the normally equable Manawatu experienced severe drought while Hawke’s Bay was awash with pasture. The stock migration reversed and prices held up well.

A mild Taihape winter can cause lamb survival rates to soar, producing a bumper crop of lambs coming out of the hills looking for spring grass to sustain them. A cold snap can do the opposite.

The location of the Feilding saleyards—in Manawatu, but also handy to the hill country of inland Wanganui and southern Taranaki, and close to the Manawatu Gorge—the main route to Hawke’s Bay and Wairarapa—assures their importance.

The relatively mild weather of the lower North Island means the supply of lambs for meat companies is spread over a longer period than it is for South Island plants. In the last five to 10 years, South Island meat companies have moved into the lower North Island in a quest to extend the seasonal supply of lambs for their overseas customers who increasingly expect chilled lamb year-round. Despite static lamb numbers in the region, the demand for those lambs has increased dramatically over the last couple of years. Construction of a plant by Canterbury-based CMP in Marton and refurbishing a plant in Dannevirke by Invercargill-based Alliance has increased the lamb processing capacity by nearly two million. Richmond, the Hawke’s Bay company that was already the biggest meat company in the country, got even bigger when it was taken over by Dunedin-based cooperative PPCS in an acrimonious corporate scrap that went all the way to the Appeal Court.

[Chapter-break]

While Saleyards are the backbone of livestock trading in the region, the area also has a high reputation for other reasons. Nearby in Feilding is the headquarters of Performance Beef Breeders, the joint head office of the major cattle breed societies. Always trying to improve the fortunes of their cattle, the societies hold all the genetic records and information on the national beef herd and also organise the National Bull Sale held annually in Manawatu.

Head north out of Feilding on Kimbolton Road and you’re on the aptly nick-named “Ram Alley” or the “Golden Mile”, home of a number of highly regarded sheep studs. The annual Feilding Ram Fair is one of the big three in the country along with Christchurch and Gore.

Two of the breeders on Ram Alley, Ross Humphrey and Richard Brown, have formed TRIGG (Terminal Romney for Improved Genetic Gain) with other Romney breeders in the lower North Island to improve the performance of their flocks.

Cooperating with Massey University academics Hugh Blair and Patricia Johnson, the breeders have identified which of their sheep have the best genetic traits for meat production by slaughtering their progeny and dissecting, measuring, weighing and evaluating every cut for its economic value. After crunching numbers for more than four years, the group now sells rams with more detailed and accurate information about the meat yield and characteristics of their offspring.

Another group of breeders, Mega Meat, are marketing a gene found in the Poll Dorset breed that increases the average size of the loin, one of the most valuable parts of the carcase.

Until recently, these exercises would have been of little commercial interest as farmers are paid only on carcase weight and fat coverage. The value of the various cuts was of no direct consequence. However, in the 2006-07 sea‑son meat company Alliance will use scanning technology to determine a yield grade for the three main cuts of the shoulder, loin and leg. Farmers will be paid according to that grade. Progressive Meats in Hastings is also introducing a yield payment system, only it is based on weighing every cut as it would appear on a supermarket shelf.

Another Massey lecturer, Stephen Morris, has been running trials on year-round lambing in some breeds. The ewes lamb five times over a two-year period instead of just once a year. While the idea is rubbished by some farmers, it is potentially significant. Think of a factory increasing its production by 150 per cent.

All these changes and scientific advances might take a while to filter through to the hard testing ground of price at the saleyards. But within a year or two they will be added to the equation of what farmers and meat companies are prepared to pay for stock at Feilding.

[Chapter-Break]

Farming has more than once been dismissed as a sunset industry. It’s a hard argument to sustain on a Friday afternoon in Feilding. Not only has the farming industry survived, it is more efficient than ever. In the 1980s, New Zealand was home to 70 million sheep. Now there are only 40 million, yet lamb export volumes are around 15 per cent higher than they were 20 years ago. The Lange government did the industry an ironic favour when it axed subsidies, forcing it to become more efficient.

While the business of sheep and beef farming keeps on changing, Feilding has built a tribute to a central character from its past. In the heart of the town is a bronze statue of a drover and his dog, a monument to the predecessors of the truck drivers. What is now accomplished within hours using mechanical horsepower and diesel was once undertaken over days, weeks and even months on horseback and foot with the help of a reliable pack of dogs.

Mobs of sheep would pour into the saleyards from all directions, orchestrated by whistling drovers and steely-eyed dogs. The droving era reached its zenith with a yarding of 52,000 sheep in 1936. Temporary pens had to be erected to cope with the influx and some of the fences collapsed, causing chaos in the wet and mud.

The job of getting the stock to their destination carried on into Saturday. Another record mentions a ewe fair that had 50,000 sheep stretched for 5 km along the Kimbolton Road north of Feilding.

Cattle were also big business with the sale-yards handling around 120,000 head a year in the late 1960s. The Hurley family from Hunterville used to hold an annual sale of their own in Feilding, which saw as many as 1000 cattle stretched along the road between the two towns. Sometimes the mob was split into two and taken down different routes to ease the congestion.

There is a certain irony in the choice of drover and dog as symbols of Feilding. They were sometimes considered a nuisance on the road and had a somewhat roguish reputation when they got near a pub. One prank involved a bet that someone couldn’t get their horse up the flight of stairs in the pub. The horse successfully negotiated the stairs—but refused to come back down. But for those who relied on drovers to get their stock to market, their skills in keeping stock in good condition and protecting them from harm were highly valued.

Drovers eventually succumbed to the stock truck, which extended the reach of the Feilding saleyards to what it is today.

Feilding now markets its centrality to the farming industry with the drover as its icon, and also its refurbished Edwardian architecture. There are even guided tours around the saleyards for tourists, an attraction that received major coverage in a Japanese newspaper.

Today the truckie is also valued for his ability to get stock delivered on time, in good nick and with the correct tally. His job is even more tricky at the end of the day. At least at the outset of sale day, he knows what farms he will be going to, but his post-sale itinerary is not set until just before departure.

While auctions continue, the truckies, yardmen and stock agents contend with the logistics of getting the right animals through the maze of races onto the right truck heading in the right direction. The air above the saleyards is alive with cellphone signals, dogs barking and yelled instructions as the mayhem of getting the stock to their new owners’ farms gathers momentum. The truckies will be driving for quite a few more hours before they can call it a day.

Feilding and the saleyards have ridden the fortunes of the rural community through world wars, booms and slumps, negotiating the amalgamations and buyouts of the many different companies that have operated there over the decades. But the yards have remained, and will remain, the central point of livestock trading and social contact for farmers throughout a vast tract of the lower North Island.