Rock stars

In the heart of the Waikato there’s a multimillion-dollar industry based on a gnat. Glowworms are big business, attracting well over half a million people a year to Waitomo and prompting some to shift from working the land above ground to commercialising the creatures below it. But keeping the caves and their thousands of tiny performance artists in good health requires round-the-clock care.

Up close and under torchlight, the larvae of the fungus gnat aren’t particularly attractive. Each one, just a few centimetres long, lies slung from the rock in a transparent mucous hammock, dangling a thicket of sticky silken threads into the darkness.

Turn the torch off, and the larvae are transformed. The rock becomes a vault of stars. All that is visible are their glowing blue-green lures, bioluminescent lights that draw insects into their trap.

In Waitomo, the fungus gnats are the star attraction. There, you can sit snug in a boat, floating beneath their ethereal lights. You can descend a wheelchair-friendly spiral pathway into a cave to see them up close. Or you can ineptly lower yourself into a damp 35-metre hole in the bushy hillside.

That last one sounded good to me, so within hours of arriving in the King Country I’m leaning out over the abyss, hoping my harness, carabiners and abseiling rack will hold. I’m dressed for action in a caving helmet, full-body wetsuit, booties and white gumboots, plus a bank-robber balaclava to stop my hair tangling in the ropes and ripping my scalp off.

The bottom suddenly seems rather far away, but one of the guides, Katie, nudges me off the metal platform, and there’s nowhere to go but down.

Green walls upholstered with filmy ferns give way to a narrow shaft called ‘the throat’. There is something anatomical about it—an intrusion into the belly of the earth. Voices float up from below, disembodied and echoing. The four others on my tour—a Canadian, a Thai, a Russian and a New Yorker—have already been swallowed by the hole.

I awkwardly let out some more rope, and the walls open out, the limestone ridged like ripples of sand. The light dims and the sky recedes to a tiny green triangle, peppered with heart-shaped kawakawa leaves. My feet touch rock, and another guide, Turtle, unclips me from the rope.

Our guides on the Black Abyss tour, run by The Legendary Black Water Rafting Company, are confident Kiwi women in their 20s. They convince us to slither into soggy wetsuits, teach us to abseil, send us careening into the pitch-dark on an underground zip line, and make us leap off a ledge into a deep, frigid stream.

In a rare peaceful moment, we float along in a conga line of patched-up inner tubes, gazing at the insect lights.

Down here, the sound of water is everywhere. High-pitched dripping is layered over the roar of the rushing stream and the thrumming vibration of water wearing down rock, carving these tunnels through the porous limestone.

After four hours underground, we leave the cave by climbing up two waterfalls. The thunder of white water through the narrow chute makes talking impossible, so the guides demonstrate with gestures where to place hands and feet. With my nose centimetres from the flow and knees jammed into the torrent, handhold follows foothold and I emerge exhilarated above the cascade.

We turn a corner and there’s daylight, and a rush of warm, life-scented air. After so many hours in monochrome, the psychedelic brightness of the green is overwhelming, like seeing in an extra dimension.

I feel like Gollum crawling out of a hole in the Misty Mountains, dripping and wide-eyed. According to Angus Stubbs, a Tolkien tragic who runs the guiding operation for The Legendary Black Water Rafting Company and Ruakuri Cave, there’s a pretty good reason for that: during the filming of The Lord of the Rings, Andy Serkis, who played Gollum, spent time in this cave getting into character.

Seven companies operate cave tours around Waitomo, with around 130 people working as guides. At least half a million people visit one of Waitomo’s caves each year, and the most popular one—The Waitomo Glowworm Cave—can pack 1500 people a day through its subterranean chambers. It’s among the most highly monitored caves in the world: its carbon dioxide and water levels constantly tracked, the stream’s ecology measured and managed, the glowworm population digitally counted every half-hour. The carnivorous larvae of the fungus gnat have become a multimillion-dollar industry.

[Chapter Break]

It didn’t start out that way. In 1884, local Māori showed English surveyor Fred Mace the yawning cavern where the Waitomo stream disappears into the mouth of the Glowworm Cave. Mace wasn’t able to go inside, but he couldn’t forget the sight. He’d spent decades bouncing around the British Empire, from London to the Andaman Islands, Bombay to Melbourne, but that year he decided to settle in Otorohanga.

Mace struck up a friendship with Waitomo chief Tāne Tinorau. They were such good friends, in fact, that after Tinorau’s first wife, Te Nekehanga Tutawa Tuatara, vacated her marriage bed to make way for a younger, more-fertile woman—she had failed to provide Tinorau with any heirs—she married Mace instead.

The two couples remained close, and on an 1887 visit to Tinorau’s kainga during the Christmas holidays, Mace convinced his friend to help him explore the cave.

They made a raft out of flax stalks, lit a pair of candles, and let the stream carry them into the darkness. Passing through a low passage, they lay down to avoid the stalactites. The pair hoped to follow the stream right through the cave, but a mass of driftwood stopped their progress. Turning back, they dragged the raft upstream against the flow, reaching daylight just before their last candle burnt out.

Over the following years, Mace and Tinorau explored further, and Tinorau and other Māori began guiding visitors through the cave. They laid ponga logs along the damp paths, installed ladders, and lit coils of magnesium wire to illuminate the formations. By 1900, each visitor was charged two shillings—20 cents.

Ellen Ida Massey visited in 1902, and later described her amazement when the Māori guide told the group to extinguish their candles.

[sidebar-1]

“I thought to myself, ‘Why, we shall be in complete darkness’,” she wrote. “Lo! A wondrous sight burst upon our astonished eyes. The ceiling of the whole vast area was softly resplendent with the lights of countless thousands of glowworms… So bright was the radiance that the rocks were reflected in the river… We relighted our candles with great regret.”

The trip was not the pleasant stroll it is today. The party climbed down slippery wooden ladders with a candle in one hand, and though Massey and the other women hitched up their skirts, by the end of the four-hour tour they were “plastered with white mud and candle grease”, she wrote.

“We all agreed that a miner’s kit would have been the best costume for such an expedition.”

The caves had already caught the attention of the government, which was searching for a new tourist attraction after the destruction of the Pink and White Terraces. It mounted an expedition to Waitomo in 1889, which reported visitors had already graffitied their names on the delicate walls. The government spent a decade trying to buy the overlying land from Tinorau and the other Māori owners. They refused.

Soon, the owners’ wishes no longer mattered. The Scenery Preservation Act of 1903 gave the government far-reaching powers to forcibly purchase land, and in 1904 the Waitomo Glowworm Cave was the first place to be nationalised. The landowners were awarded £625 in compensation (equivalent to about $108,00o today). Tinorau died before it was paid, three years later.

The Tourist Department established a hotel, installed iron railings and concrete staircases in the Glowworm Cave, and then the government nationalised two nearby caves, Ruakuri and Aranui.

Waitomo quickly became the Tourist Department’s most profitable attraction. The caves were so famous that Queen Elizabeth asked Prime Minister Sidney Holland to arrange a visit to Waitomo as part of her 1953-54 New Zealand tour.

[Chapter Break]

Visitors to Waitomo should be dry and comfortable—that was the logic of the Tourist Department. Caving was for speleologists.

Then Pete Chandler started taking backpackers through Ruakuri Cave in old inner tubes, and calling it black-water rafting. A friend had invented the name down at the pub as a laugh. “But it soon stopped being a joke,” says Libby Chandler, Pete’s wife.

Pete had an old Austin ute, and in 1987 he and Libby drove it up and down Waitomo’s main street trying to convince tourists to join them. Their caving trip cost $10 and came with a hand-drawn poster to put up in youth hostels around the country.

“You’d ask people if they wanted to do this black-water-rafting adventure, and most people would have no idea what you were talking about,” says Pete. “People wanted to come and see glowworms, so it was a caving trip that really featured glowworms as an integral part of it.”

It was pretty DIY—the tourists were stuffed into the back of the ute wth the inner tubes—but it was popular within weeks, and that summer the Chandlers hired their first employee: 19-year-old Angus Stubbs.

As demand grew, other companies started offering black-water-rafting tours, too, and a battle over naming rights divided the small community. Pete Chandler and his business partner John Ash were granted a trademark on the words ‘black-water rafting’ in 1998.

“We felt like it was our idea, and we’d come up with an original trip with an original name,” says Libby.

Nick Andreef, who has also been running caving trips in Waitomo since the late 1980s, opposed the Chandlers’ monopoly of the name: “It’s like white-water rafting—they are both generic terms,” he says.

The case ended up in court. In 2002 a High Court judge decided in favour of Andreef, and the trademark was expunged.

[Chapter Break]

“So when you were on the Black Abyss tour, the guides said they would catch you if you panicked and let go of the abseiling rope, right?” asks photographer and caver Neil Silverwood.

Yep. I remember.

“If you do that here you’ll fall all the way to the bottom, so don’t let go.”

Silverwood wants to give me a taste of ‘wild’ caving, so he’s taken me to a cavern called Lucky Strike, not far from Waitomo. By cavers’ standards, it’s an easy trip—a bit of abseiling, climbing and stream-following—but it’s more intense than any commercial tour. In 2008, a woman was rescued after she broke her hip falling into the stream. Thankfully I didn’t hear about that episode until after we’d surfaced.

At one point, we climb a small waterfall, aided by a broken rope ladder. I scrabble at the rocks as the stream pours into my face, but lose my grip and fall backwards into a deep pool. It’s exhausting. Eventually, Silverwood hauls me up through the narrow hole by my armpits. But that’s what caving is about, he says. There are no prizes for elegance, and it’s a group effort.

In a low chamber near the top of the cave, we run into three recreational cavers. One of them, Mike Allen, lives in Auckland and has been caving for 25 years, the past 15 in Waitomo. Mystery, adventure and the lure of the unknown drew him to the sport: “You just don’t know what you’re going to find.”

Recreational cavers discovered, explored and mapped many of Waitomo’s caves from the 1950s onwards. But as the tourism industry grew, and commercial companies began to lease the caves, some locked cavers out, says Allen.

“Not having access to certain caves in Waitomo, when the caving community actually found those caves, surveyed them and put a lot of work into them—it’s a bit of a poke in the eye really.”

Cavers have a good relationship with The Legendary Black Water Rafting Company, he says, so they can often get permission to explore the caves leased by THL. Some of Waitomo’s most spectacular underground landscapes, though, are leased by Nick Andreef, who doesn’t allow recreational cavers in.

“When we first got to the Lost World [cave system], cavers had been in there first, and they’d wandered all over the bottom of the tomo and trashed all the plants,” says Andreef.

That included a colony of Asplenium cimmeriorum, a rare, slow-growing native fern that flourishes in the low light of cave entrances.

“If they’re real cavers they’ll be off finding new caves,” says Andreef. “There are 300 surveyed caves and maybe up to a thousand total caves in the Waitomo area—why do they have to bother with the 20 or so commercial caves?”

Increasingly, tourism operators see themselves as cave custodians—and they’ve got a good business reason for that. As visitor numbers rise, keeping the caves intact and the glowworms alive is critical to the industry’s survival.

[Chapter Break]

“This environment has not changed for thousands of years, and these little glowworms have been here the whole time,” says Stubbs. “When the Egyptians were building the pyramids these creatures were living here, exactly like this. We’re 60 metres below the surface, and I can see your expression—just because of this little insect.”

Stubbs may be in management these days, but once a cave guide, always a cave guide. He reckons he was born to it. His family has farmed in Waitomo for generations, and when he was a child, his father let the Auckland Caving Society take over his great-grandfather’s tumbledown old house to use as a club hut. They’re still there. Stubbs says he grew up meeting “all these amazingly interesting and weird people.

My mum and dad would just kick my brother and me out the door in the morning and say, ‘Go and hang out with the cavers.’ Because we were little, they would tie ropes around us and lower us down holes to see where they went. We found lots of sub-fossil bones—moa, tuatara, kiwi, kākāpō. I loved it.”

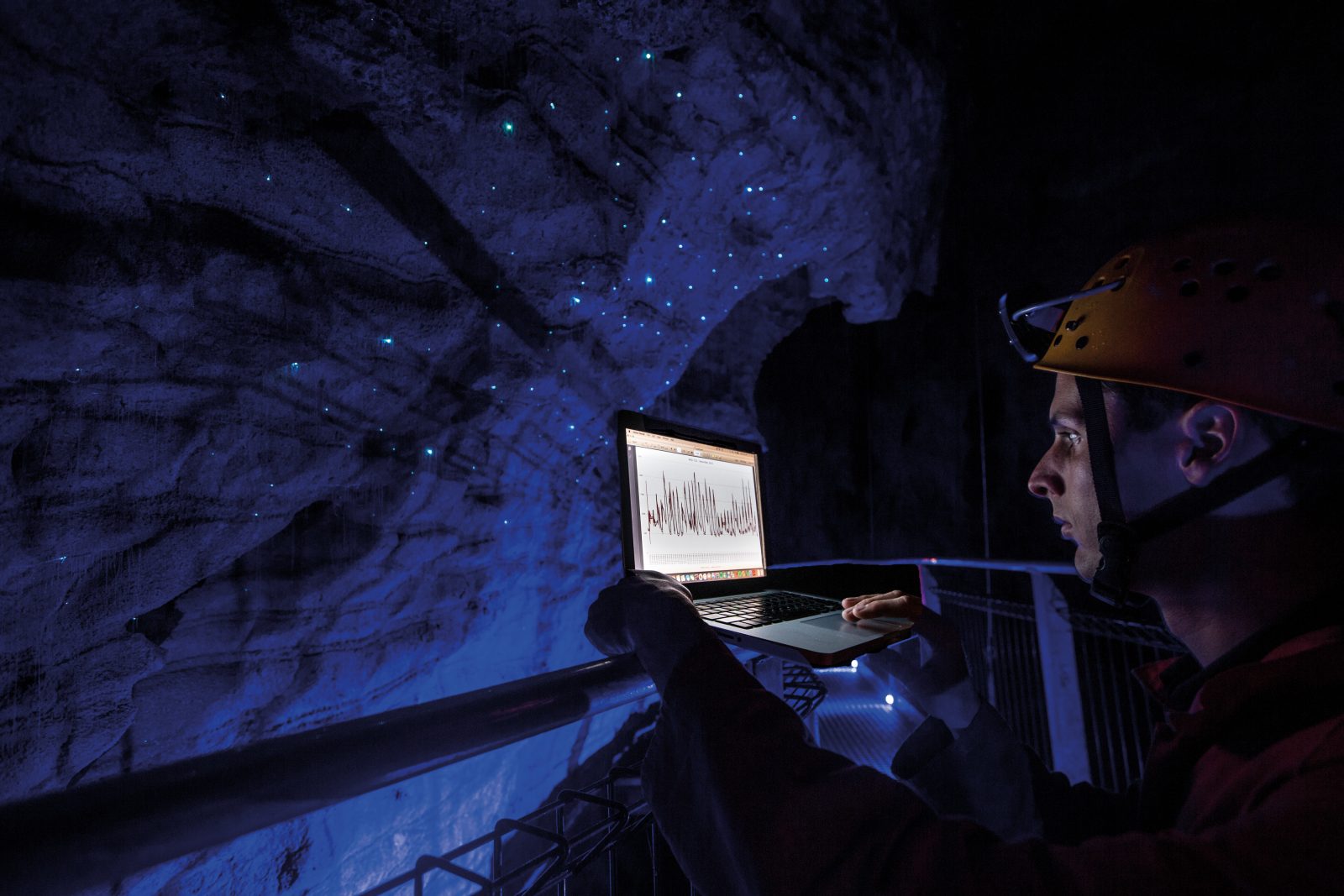

Stubbs has brought me to Ruakuri Cave, along with THL environmental officer Carl Fischer, to show me the behind-the-scenes work that’s gone into protecting the cave since it was reopened in 2005.

The first tourists were guided through Ruakuri in 1904 by James Holden, who had recently acquired the land above the cave entrance. Two years later the government nationalised it, and the state-owned Tourist Hotel Corporation ran tours until the late 1980s.

Then Holden’s grandson, also named James, discovered that much of the vast cave still ran beneath Holden land, and challenged the government’s right to conduct tours under his property. He stuck a no-trespassing sign in the cave, closing Ruakuri for the next 17 years.

“James Holden asked the question, ‘Who owns a cave?’” says Stubbs. “So now, if someone owns the piece of land above a cave system they can negotiate royalties and leases with people who want to use it.”

Reopening Ruakuri required a decade of negotiation between THL, the Holden family, the local iwi, the Waitomo District Council, and the Department of Conservation.

Iwi wanted the original cave entrance to remain closed, as it is a wāhi tapu, or burial site. That meant creating a new entrance without changing the airflow or humidity of the cave, which could have threatened the glowworms.

On the other side of the hill from the wāhi tapu was an old entrance called the Drum Passage, pioneered in the 1960s.

“You had to bush-bash your way down, lift up this old rusting lid, and then there were these rusty creaking old 44-gallon drums disappearing down into the ground,” says Stubbs. “You’d carefully squeeze your way down the first four metres and then you popped out into a sort of mud puddle at the bottom.”

To create a new entrance, THL sank a hole away from the cave system, then tunnelled through a rock fall to connect with the Drum Passage.

“We said to the workers that if they broke anything they would get a $10,000 fine—and we hung little $10,000 tags off the really special formations,” says Stubbs.

One stalactite was chipped—but the culprit didn’t own up to it.

[sidebar-2]

Now, instead of squeezing through rusty drums, visitors enter through an airlock and wind down a spiral ramp that looks like something out of a space station. A second airlock protects the entrance to the cave.

Inside, suspended metal walkways keep visitors’ feet far from the fragile cave floor, and sensors set off an alarm if anyone reaches toward the delicate stalactites and stalagmites (collectively known as speleothems).

It’s light-years from the way the Waitomo Glowworm Cave was developed in the 19th century, says Fischer.

“At that time the whole world was a frontier and everything was infinite. They didn’t understand the timescale they were dealing with so they just went for it. But now we do, so there’s a lot more consideration for the environment.”

It took a massive glowworm die-off in the 1970s to finally focus attention on cave preservation. Concerned about rising carbon-dioxide levels in the Glowworm Cave, its managers enlarged the entrance and replaced the wooden door with an open grille.

“It was super effective—it did flush out the CO2—but what they didn’t foresee was that it would quite radically alter the cave microclimate,” says Fischer.

The grille turned the cave into a wind tunnel, which dried it out. Glowworms need at least 90 per cent humidity to thrive. It may also have created more favourable conditions for a fungus that preys on glowworms, says Fischer.

“The result was that they pretty much all went out, and the cave closed for several months.”

Scientists have since learned a lot more about glowworms and the climatology and ecology of their subterranean homes. Fischer monitors them closely. Data on water levels within the cave and at the Waitomo stream’s headwaters can be easily accessed via his mobile phone, and alarms go off if a flood is likely.

Electricity is necessary to illuminate walkways and formations, but light is alien to caves, says Fischer, and it allows the growth of lampenflora—algae and other plant life—where none would occur naturally.

Ruakuri’s lights use a spectrum that’s not easily photosynthesised, and they’re on automatic timers, so groups travel through the cave in a lighted bubble. When greenery does appear, Fischer treats it chemically.

More challenging is a threat that can’t be seen: carbon-dioxide levels, which are influenced by visitor numbers and climatic conditions and could damage the cave’s iconic limestone formations.

When water enriched with carbon dioxide and calcium carbonate emerges from cracks in the rock and is exposed to the air in the cave, it releases carbon dioxide as gas and deposits calcium carbonate in the form of stalactites and stalagmites.

But when too many tourists exhale in wonder, the cave air ends up holding more carbon dioxide than the water, and the process is reversed.

“So, instead of that water depositing calcium carbonate it will continue to become more acidic and begin to corrode the formation,” says Fischer.

This matters most in the Glowworm Cave, which receives the highest numbers of visitors. Fischer is responsible for postponing tours or closing the cave.

“It can be a pretty full-on job sometimes, because carbon dioxide isn’t just a function of how many people go in. There are other things going on too—the ventilation in the cave, and there are carbon sinks in the cave too and they’re in flux.”

“You have to see what the weather’s doing, and judge how many people are going in.”

Keeping the caves’ invertebrate performance artists happy and well fed is something he has less control over.

“Because their prey emerges from the stream, glowworms are really vulnerable to changes in the catchment, like deforestation or agricultural intensification.”

That has prompted collaboration between tourism operators and other land users, especially farmers. Since 1992, the Waitomo Catchment Trust has worked to reduce the silt flowing into the Glowworm Cave, and improve the stream ecology, by tackling erosion in the catchment.

Caving companies and the council contributed money to offer incentives for farmers to fence riparian strips, reforest steep areas, and avoid cropping on erosion-prone slopes—and many did, says John Ash, who was one of the Trust’s founding members.

“All the drainage from the whole catchment goes through what we call the ‘plughole’—the Glowworm Cave—and it has international significance as a tourism icon. So when you’ve got that sort of thing you can hang up, it’s a lot easier to get people on board.”

Glowworms make it easy to understand why stream health is important, says Fischer.

“In other areas, you have this diffuse problem of water quality and no single, easily understood set of impacts. But here, people understand that glowworms depend on the insects in the cave, which depend on the amount of sediment and organic matter in the stream—and the community depends on the glowworms.”

The heavy door clangs shut as I follow Fischer and Stubbs out of Ruakuri, and we squint in the late-afternoon light. Stubbs has been in the glowworm business for 30 years. He’s still delighted by them.

“Caves in this area are nowhere near as good as caves in other parts of the world, in Europe or China or North America,” he says. “They’ve got cave art, or prehistoric stuff, or massive formations. But here, we’ve got glowworms. That’s our point of difference.

“We really lucked out with these little beasts. Nowhere else in the world can you see an insect perform like this—they’re just magic. That’s why we’re doing all this—to make sure we keep them alive.”