Rock hounds

The Nelson area is one of New Zealand’s richest for minerals. Here, obsessives comb rivers for unusual and precious rocks. Yet despite these people’s shared passion, friction abounds within the community, raising questions: who owns the precious stones that tumble down rivers in the public estate? Can anyone take them? And, if so, can they sell them? Should they?

When Jen Hoolihan found the meat rock, she had been fossicking for hours up the Wairoa River outside Richmond. The rock was weathered and pinkish—totally unremarkable to the untrained eye. It sat submerged beneath the water, perhaps carried down from the mountains in the last rainfall. Hoolihan reached out with her G-pick, a kind of pointed hammer, and prised it free. She knew exactly what she was looking at.

“This is dunite,” she says, running her fingers across the surface of the stone. “There aren’t many places in the world where you find it on the surface. It’s normally found deep within the Earth’s crust. So many people walk over it because it’s quite boring, but when you cut it open, it’s these beautiful shades of green. My son and I lovingly refer to it as the meat rock because, well… it kind of looks like a piece of meat.”

The meat rock could equally be called the potato rock—it’s a long ovular stone the size of a large kūmara. But where it has been sliced open at one end, the orange crust gives way to an astonishing emerald colour, which Hoolihan has polished to a glassy finish. Dunite was first discovered and named in the Nelson region—it takes its name from Dun Mountain in the Richmond Range. “So I have a particular affinity for it. This is our rock.”

Hoolihan’s earliest childhood memory is running in the desert of South Australia looking for fossils with her dad, a geophysicist. “I must have been about two or three. But he wasn’t interested in what I was finding. He was trying to get my brother into it, who wasn’t interested in it at all.”

We are sitting in Hoolihan’s lounge near the beach in Nelson, surrounded by rocks extending outwards from the centre of the room, positioned in hierarchical fashion from best to worst. Not in terms of monetary value, but in terms of their individual appeal, much to the frustration of Hoolihan’s rockhounding friends.

“I’ve been trying to learn to ‘catch and release’, not to get attached to every rock I find, but it’s like—they’re all the best one,” she says. “I’m not always looking for a particular kind of rock, it’s more like, ‘Oh, that has a nice colour. Oh, that has a nice texture.’”

Outside, on the deck, are hundreds of rocks awaiting sorting. Hoolihan opens the ranchslider, takes a bottle full of water and pours it across the stones, caressing the surface of each to bring out the colours below.

“I’m not a geologist. I don’t really know bugger all. I just love rocks,” says Hoolihan. “They’re ancient, they’re so old, and that’s so beautiful. They will always be here. God, I sound like a bloody stoner.”

“She is obsessed with rocks,” says her son Jasper, who is named after the brightly coloured silica. “If she could have another child, it would be called Grossular Garnet.”

So what is it about rockhounding that’s got Hoolihan—and others like her—so hooked? “I think part of it is that when you’re on the river, everyone is equal. There is no gear that is going to help you more than someone else. It’s free, you’re out in nature, and everyone is equal. It’s meditative and it’s hypnotic.”

[Chapter Break]

Around 280 million years ago, molten lava from the Earth’s core began to ooze through the crust on the margin of Gondwanaland. As the continent from which New Zealand was formed drifted into the Pacific, this lava cooled and created the conditions that formed the Nelson mineral belt, some of the most ancient rock in New Zealand. Elsewhere in the country these minerals are buried deep beneath layers of sediment and dirt, but due to intense tectonic movement and upheaval in the Nelson area, they have been forced to the surface, creating a unique and irreplicable geographic feature.

“You’ve got an awful lot of changes in geology in a very small area,” says structural geologist Simon Cox, a principal scientist at GNS Science. “There is a whole series of different mineral basins and bowled ocean crusts and things that have been stacked up like a whole lot of different books on a bookcase. Plate tectonics shuffled the books up, put them on end, and as a result you have this beautiful library of geology.”

Due to the unusually high levels of nickel, cobalt, iron and magnesium in the soil and rock here, unique high-altitude plant life evolved to adapt to the conditions. As erosion and tectonic movement twisted and crumbled the stone, it was carried into the valleys and rivers that flow down from the mountains towards the sea. Early Māori discovered the mineral belt and harvested stone like pakohe (argillite) through intense fire and rapid cooling, dragging chunks from the earth to be cut and knapped. But in many of the region’s rivers the rocks lie still—until the keen eyes of one of the many local fossickers spot them. These rockhounds spend their time combing riverbeds for argillite, jasper, garnet and—depending on who you ask—nephrite, better known as pounamu.

[Chapter Break]

Dan Cunningham is sitting by the side of the road eating a pie. On the picnic table between us is a collection of rocks, including a smooth and hefty orbicular stone like a loaf of bread dusted with blue-tinted flour. It is, he says, “blue jade”. Others in the rockhounding community believe it isn’t—that it doesn’t occur in the Nelson mineral belt, and that Cunningham has collected it elsewhere. As we speak, I notice my hand resting on the stone. It has a comforting presence of sorts. I wonder if I’m going nuts.

There are two types of rockhound, says Cunningham. There are those who hunt for beauty, and those who hunt for value. He’s both.

“I’m a treasure hunter, always have been. I’ve done a lot of hard yards and I’ve learned how to read these lines and I’ve learned how to find the good ones. I love rocks, geological specimens, but my main focus is valuable ones.”

Cunningham makes a lot of claims: that he was the first to discover blue nephrite in Nelson, that pounamu poachers helicoptering the mineral out of the West Coast offered him a slab, that he has a psychic connection to the rocks he finds.

What is certainly true is that he finds a great many valuable rocks, more than anyone else, and that he’s bitter about the ownership of pounamu being returned to Ngāi Tahu, as that made it illegal for him to collect nephrite from rivers south of Nelson. At the time, he lived on the West Coast, and the decision put him out of business. “If the New Zealand government gave me what they gave them, I would be a billion-dollar guy, too,” he says.

Unsurprisingly, Cunningham has a mixed reputation—he’s been blocked from several rockhound Facebook groups. They say he’s racist. He reckons they’re jealous. “This is why people hate me—I’ve found so much, and I’ve found incredible shit. I’ve got a nose for it. I talk to the rocks. I just have a feeling. A little bird pops up and says, ‘Right over here,’ and sure enough. They say it finds you and maybe that’s true—it sure likes me, man.”

You can tell a rockhound from the piles of stones outside their house. And that’s how photographer Andrew MacDonald and I find Cunningham’s place a day later. It’s early spring, and the flowers in the garden are blooming, while chickens pluck and scratch at the driveway. Out the back is a rock collection that makes Hoolihan’s look small and orderly, but inside is where the real quality stuff is kept.

Giant slabs, as thick as chopping boards and as wide as oven trays, are stacked around the lounge. Staring into the stone is like looking at the surface of a planet, the swirls and eddies of colour like alien gasses whipped and frothed by cosmic winds. There is an almost unbelievable depth to each one. Peering at them up close reveals near-infinite layers, as if the slab is a glass slide of petrified liquid. Cunningham holds one up beneath a light, revealing the flecks of silver that dot the stone.

“See all these speckles? That’s platinum. It’s worth more than gold.”

Outside, Cunningham demonstrates how stones can be cut like bread to reveal their quality, and how they can be processed further into jewellery and export material. He fixes a stone to a plywood board with glue, then screws the board down beneath a drop saw. A hose runs over the blade to reduce dust and assist the cutting process. While I slurp away on a banana passionfruit harvested from across the fence, the saw descends on the stone. On contact, it emits a tinny, metallic hiss.

“You hear that?” says Cunningham with a grin. “That’s the sound of good stone.”

[Chapter Break]

Early Māori were expert geologists. As they had arrived in Aotearoa without iron or steel, surveying the local stock and understanding the properties of the various resources in the rohe was a matter of survival. Harder stones would be fashioned into hammers, adzes and other tools. Softer stones became adornments or taonga.

Geologists believe nephrite and bowenite, the minerals Māori class as pounamu, were formed as deep as 10 kilometres within the earth. As the mountains of the South Island rose, these veins were pushed towards the surface. The pressures of glacial action and river currents dislodged fragments from the host rock and carried them downriver towards the sea.

The mythological origins of pounamu are shrouded by history. But according to Dan Hikuroa, earth system scientist and senior lecturer in Māori studies at the University of Auckland, pounamu is the fragments of Waitaiki, wife of the chieftain Tamaahua, who was kidnapped by the taniwha Poutini and metamorphosed into stone before her husband could rescue her. Pounamu can be found at the sites Poutini visited as he fled Tamaahua down the west coast of the South Island.

The term pounamu is a categorisation based on mātauranga Māori. So, while pou may be classified as nephrite or bowenite by Western science, in te ao Māori the stone is categorised as kawakawa, kahurangi, īnanga or tangiwai based on its visual and tensile properties.

In 1997, the Ngāi Tahu (Pounamu) Vesting Act returned the vast majority of South Island pounamu to the ownership of the iwi, with the exception of pounamu found in the Arahura River, which is vested in the Mawhera Incorporation. Under the legislation, the public can fossick on the beaches of the South Island so long as they take only what can be carried by hand on any given day. The use of powered machinery is banned, and heading up-river is off limits to all but the iwi authority.

In 2020, Lisa Tumahai, kaiwhakahaere of Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu, warned that illegal pounamu sales were booming on the black market as gangs sought to diversify their income during the COVID-19 pandemic. Meanwhile, the pounamu reserves in Nelson are not covered under the Ngāi Tahu Vesting Act—people are free to collect whatever they can carry from rivers not on conservation land—which means that rockhounds may be having a significant impact on it.

“You have a limited resource sitting in the rivers,” says Cox, the GNS Science geologist, “and if you start taking it out, you have a natural rate of replenishment by erosion from the river banks and the source rocks, but the rate of gravel turnover in those rivers is lower because of the amount of rainfall compared to the West Coast. You have a conveyor belt on which you have a number of stones which get brought up to the surface, and if you’re picking them off at a faster rate than they’re replenished, it becomes depleted.”

The legality of fossicking is a European construct, says Cox. And so, while the laws that govern the gathering of stone may allow for the collection of small amounts of pounamu in Nelson’s awa, ethical concerns still exist.

“You can call pounamu ‘nephrite’ as a mineral construct as a scientist, which I do, but that’s only half of its value. In fact, the thing that you’re dealing with has a spiritual value.

“I don’t think that it’s right to be selling material like that from a place like that, but that’s just my personal perspective. I don’t think there’s any legal reason why you can’t, but it’s where you place the importance of that spiritual element.”

[Chapter Break]

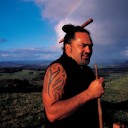

Up the Aniseed Valley, next to the Roding River is the plot of land that carver Timoti Moran calls home. It has all the trappings of a typical Nelson commune: an immobile house truck, a longdrop toilet, and free-range kids on a motorbike. Moran’s self-built workshop looks out over the field and away across the road above the awa.

The site has spiritual significance to Moran’s whānau. One night, after his construction business went under following the Christchurch earthquakes, Moran had a series of dreams in which he was visited by

a taniwha.

“The taniwha came up and grabbed me and pulled me out of the house to the gate. I hadn’t had a dream like that since I was a kid. I went back to bed and had the dream for a second time: same thing, dragged down, but this time to the paddock.”

When Moran went back to sleep a third time, he found himself being pulled down to the riverbed. Waking in tears, he called his older sister, who was more closely connected to his family’s Māori heritage.

“She really ripped into me. She was going to kick my arse, because as a youngster I was always a tutū, going where I wasn’t supposed to, touching what I shouldn’t, getting smart, and she thought I’d done something wrong.”

In the morning, Moran decided to go to the river, loading his wife and kids into an old four-wheel-drive and driving through the gates.

“We parked, went down the pathway, [and] right where I’d been dragged into the water in my dream was this stone. The pou.”

Moran’s first instinct was to sell it. Local and international markets are desperate for high-quality pounamu, and outside the rohe of Ngāi Tahu and the Arahura River, there was nothing to stop him. But despite—or because of—his early attempts at monetising his discovery, things went wrong.

“We thought we were going to get rich—not even, eh? We thought we’d make money selling stones on Trade Me, and there are people who do. I’ve befriended some of them; some of them I can’t stand. The first thing my son and I did was spend a week on the river, picked up a load of rocks, put them on Trade Me, and everything collapsed.”

Suddenly, no one wanted to buy the stone. “We thought, ‘Okay, we’re doing something wrong.’ We changed our mindset, took all the stone off and gave away most of what we’d collected for headstones—some of them were up to 100 kilos, about $9000 worth as a raw stone—and said, ‘No, whānau can have these for free,’ and freighted them out. And then things exploded again.

“I realised you’ve gotta be tika right up the middle. You can’t talk bullshit, you can’t lie, you can’t steal, and you can’t change your story. It’s something you can’t do. We’re dealing with a taonga that’s hundreds of millions of years old.”

Moran now believes that the dream was sent to him as a sign that he should learn to carve. The first year, as he experimented in his shed, he says his whānau lived on about $11,000, surviving on home-killed meat and a vegetable garden. The next year was around $12,000. But as word of his work spread throughout te ao Māori, contracts with the Kingitanga movement and other iwi groups meant that today, Taonga by Timoti supports the Moran whānau full time.

“We live humbly. This valley has always been a garden where stone and trees and tuna were harvested, so we were fine for kai. But unless I had that whakapapa, I would not have had the dream and I would not have been able to carve and nor would I be freely allowed to find it [pou] as I have since then.”

Harvesting pounamu changes the 300-million-year-old story of the rock, says Moran. When you find pounamu, you know that for the first time in its history, the stone has had human contact. The oils from the carver’s hands mix with the wairua of the stone.

“We take it home, cut it up, carve a beautiful piece from it, gift it or sell it, and then for a very small amount of time—a window of 70 years or however long I’m here—I’ve been a part of its life.”

Operators like Cunningham, says Moran, are unscrupulous in their harvesting of stone and in who they sell it to. He believes pounamu has been illegally collected from Department of Conservation land, and suspects some people in the area are using powered machinery to pull larger, more valuable stones from rivers.

“Honesty is all you have,” he says. “All we really have that is ours is our word, and everything else is superficial. Pounamu allows me to cut away all the dross like a sharp knife. It allows me to do what I do.”

[Chapter Break]

It’s a Saturday morning at Rockfella’s Cave in Motueka and there are already three or four customers bringing stones to be cut, waiting anxiously to learn what geological prize is hidden beneath the crust. They talk trade: war stories, the conditions up this creek and that, the stones being found in the area and whether someone else’s finds were just straight-up stolen.

The customers are a diverse group— rockhounds, mums, old ladies, young girls in crop tops looking for TikTok crystals. Inside the shop there are baskets of jasper, rose quartz, hematite, citrine, agate, carnelian, selenite, lepidolite and other minerals not found in the Nelson area. There are stone buddhas and ceramic dancing sufis and guides to fossicking and a big wooden elephant head, upon which the Rockfella himself, Dave Dunning, sits to examine a sample.

Inspecting the gnarled and pitted surface of a boulder, he warns that what is inside is unlikely to be anything particularly special. But his customer doesn’t care—he found the rock with his daughter on a walk, and they want to see what’s within. I feel like I’m the only one in the room missing the optical illusion that transforms this unremarkable hunk of stone into a rare find worth lugging shin-deep through a river.

“There is crap in the marketplace,” says Dunning. Bad actors pass off low-quality rocks as valuable when they’re not. “You can get really shitty serpentine and serpentine that’s as good as any nephrite. It’s in the cooking.”

Dunning says rocks are “like scones in the oven”. And as every baker knows, a scone can be overcooked and dry, or it can come out of the oven too early.

Some rockhounds, says Dunning, are running a scam, artificially inflating the value of the stones that they find and sell in the Nelson area, mostly by capitalising on people’s ignorance, or the confusion over the meaning of “jade”. Jade is popularly used to refer to two minerals—nephrite and jadeite. Jadeite isn’t found in New Zealand; nephrite is. But if you’re selling to international customers, everyone recognises the word “jade”, and it sounds a lot better than “nephrite”, while the word “pounamu” often doesn’t mean anything at all.

“It’s simply a money-making thing,” says Dunning. “It’s wrong on every level. They’re not respecting the rivers. They’re not respecting the stone. They’re not respecting the people they’re conning.”

[Chapter Break]

For many of the region’s enthusiasts, profiting from rocks isn’t the point of fossicking. For Paul Egan, gumbooted with G-pick in hand, rockhounding is about the sound of the river, the fresh air, the views. “It’s just another form of being out in nature.”

It shares similarities to hunting, he says. There is the searching-and-shooting aspect, but also the learning, planning, research, map-reading, and poring over the accounts of old rockhounds. Just like fishing or surfing, every rockhound has their secret spot, each with its own nickname: “dead sheep”, “pebble bed”, “the vineyard”. That knowledge is hard won and jealously guarded.

“You don’t broadcast your spots. If you’ve done the mahi, splashing up rivers, talking to people, dragging out rocks, you don’t just give that away to people who haven’t done the work.”

He’s right—your eyesight begins to change when you start rockhounding. It’s an effect I first noticed when staring at trees in the Melbourne Botanical Gardens. As my friend began to describe which tree was which, and what separated them, and the functions of various shapes and sizes, I started to see the trees I had been missing for the forest. It’s the same with rocks. Suddenly, splashing up the Roding River, I’m not walking over slippery stones, but greywacke, jasper, garnet and

serpentine.

For Egan, like Hoolihan, the politics of rockhounding is less interesting than the experience. While Egan is more of a purist, collecting only select specimens from the river, the thrill is the same.

“What is in the river is like a deck of cards,” he says. “When it rains, they get shuffled up.”

Cupping water in his hands, he rushes across the riverbank to throw it on a possible find, scrubbing at the dried mud and revealing the grossular garnet below.

“Not good enough.” He sighs. “I’ve been spoiled.”