Riding Giants

Catching the monstrous swells that roll around the hip of the Catlins Coast, big-wave surfers challenge nature’s greatest forces simply for the rush.

As a relieving lighthouse keeper in the early 1970s, I was posted to some of the most remote and exposed parts of New Zealand’s coastline, where I managed to find and surf some demanding waves. Rarotoka or Centre Island was one of the most isolated—a 96 ha island 16 km offshore in the treacherous Foveaux Strait.

When I climbed out of the little Cessna with my surfboard and pack, the relentless Roaring 40s were blasting the island with showers of hail and sleet and pounding it with huge waves. It was 1973, and the furthest I had ever been south.

At that latitude (46.5ºS), prevailing west or southwesterly winds whip up ocean swells and push them uninterrupted beneath Africa and Australia. They grow in size and gather in momentum until they slam into the Fiordland coast, funnel through Foveaux and collide with Rarotoka.

The western end of the island has been eroded by these massive forces into a triangular reef. To shipping it’s a hazard, but to a surfer’s eye, the reef splits any swell of six feet or more, causing it to peel off as a powerful left-breaking wave.

I remember staking out the surf from the lighthouse tower, ogling at these well-formed waves. My afternoons were spent studying the line-up, planning how to get in and out safely, and waiting for the right moment.

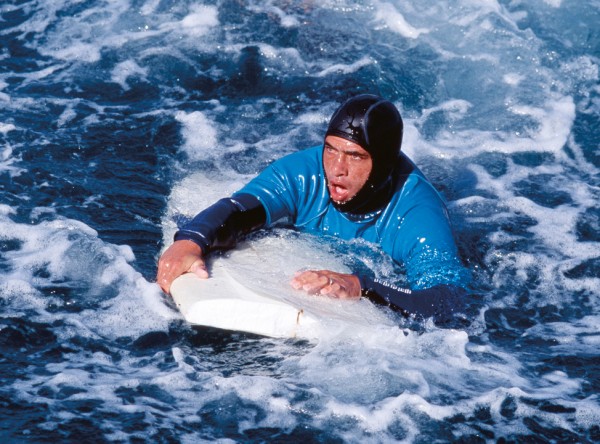

One day, after weeks of hesitation, conditions were perfect, and I took a leap from the rocks. With my heart thumping, I paddled through the boulders to the point where, from my lighthouse, I had observed the wave peaking. Powerful currents made it difficult to hold the position and I felt insignificant, a dot in a mighty sea.

I let a couple of waves go through to confirm the takeoff spot, and then selected a wave. Paddling my heart out, I stood up and committed to the drop—a fleeting but perilous freefall down a near-vertical wave face. Failing to complete the first “bottom turn” would put me in the belly of the beast and dash me without mercy upon the very reef i was warning people to avoid.

I leaned hard into a turn, the wave hissing loudly behind me as a liquid wall loomed in front, looking as though it would swallow me. Instead, I came skittering out onto the broad shoulder of the wave like a bullet from a gun, the lip exploding behind me with a roar.

The waves were about 8–10 ft and I began feeling confident, taking off a little deeper on each wave. Eventually I was caught, driven to the bottom and bounced off the boulders, tumbled upside down and shaken like a rat in a dog’s mouth.

I was held down for a long, long time. Freezing cold and running out of air, I remember thinking that I could drown, and that no-one would even know.

I reached the point of giving up, and in the moment that I became relaxed to my fate, I bobbed back to the surface and gasped a welcome breath.

When I first leapt into that cold southern water, it was a pivotal period in surf discovery. “Steamer” wetsuits hit the market and primitive leg ropes were being developed. Both made surfing in cold water bearable and enabled surfers to paddle to locations they wouldn’t go before. Since then, other technological developments have opened up new surfing opportunities, allowing surfers to brave larger and more dangerous waves. Now, using jet skis, there is the opportunity to get flung into waves that can’t even be caught by paddling. (The ski driver also picks up his tow-partner after each ride and whisks him back out to catch another in safety.)

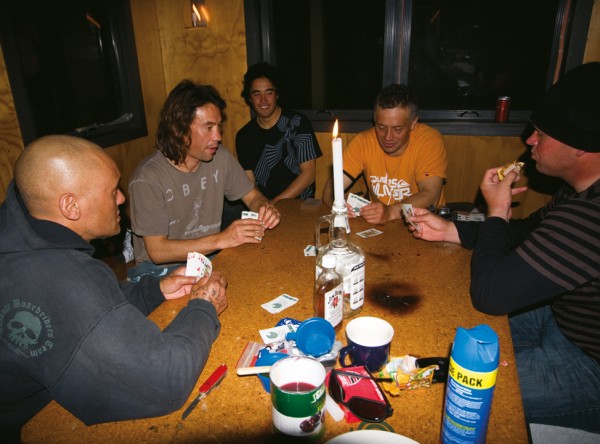

A three-foot east coast swell in warm water may be luxurious, but it isn’t everyone’s dream surf experience. New Zealand’s most celebrated big wave surfer, the effervescent Doug Young, and a dedicated band of like-minded southern men regularly make mid-winter pilgrimages to a small settlement on the Catlins coast, lashed by big weather and waves that can rip you apart. It’s the Aoraki of New Zealand waves: Papatowai—reverently, almost affectionately, known as Papas.

High profile surfers will come from the North Island to ride them (like Daniel Kereopa, Campbell Farrell and Miles Ratima) or from Australia (like Ross Clark-Jones) but the regulars are Dunedin locals, a bunch so small you can list them by name—Kyle Davidson and Jamie Gordon, Taane Tokona, Oscar Smith, Dale Hunter, Todd Robertson, Shane Baxter—and Doug Young, who makes the journey from his Christchurch home.

Young is quick to acknowledge others who show up from time to time, insisting that every surfer who jumps off the rock and paddles out deserves credit, but in reality he is an exception. At 33, he has carved a career out of his passion and is perpetually on call for the biggest waves on the planet.

“If you are locked into your job and your commitments, you miss swells,” he says. “The worst thing ever would be to hear that Papas broke at 20 ft and I wasn’t there because I had to work.

“It’s just this amazing sense of achievement and fulfilment. It makes us who we are, and that is why we do it, because of that sense of achievement.”

[Chapter Break]

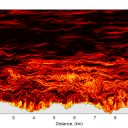

Oceanic swells have a long wavelength, and are the only waves attaining the necessary size for big-wave surfing. They are created by wind blowing over water causing ripples to accumulate as lines of swell. The size of a swell is a function of wind speed, the duration it has been blowing and the distance of water, or fetch, that it is blowing over. A “ground swell” of long period waves will have travelled a great distance and have more momentum or power than a similar-sized wind swell with a shorter interval between waves.

When swells reach shallow water or pass over a shelf, the bottom of the swell slows down, forcing its energy to be amplified upwards and in breaking it becomes a wave. Whether it spills, crumbles or pitches from the top depends on how rapidly it has become shallow and how deep the obstruction is in relation to the size of the swell.

The height of a swell is the vertical distance from the trough to the crest registered by the rise and fall of buoy readings at sea. However, the underwater contour of a beach or reef will cause a swell to “jack up” suddenly and exceed its swell height at the moment it breaks.

Surfers measure waves and surfboards using the imperial system of feet and inches rather than metres. The standard used to describe the size of waves in this story is known as the “apparent vertical measure of wave height” and is based on the height of an average person slightly crouched, that is five feet, viewed in relation to the wave thus a wave two people tall from the trough to the crest would be roughly 10 ft.

Sometimes, when a wave hits shallow water abruptly and breaks with ferocity, it may “throw” its top violently forwards and form a perfect cylinder known as a barrel or tube, the most coveted hydrological effect in the surfing world.

The best surfers become intimately acquainted with these physical principles, able to read the behaviour of a wave, anticipate its unique response to the underwater topography and place themselves ready and paddling at the point at which it will break. It is a constant process of rapid, accurate decision-making. As the surf gets bigger, all factors are magnified and the consequences increase greatly.

Kyle Davidson suggests that the best big-wave surfers learn to become patient and calculating because of the high risks involved. “Surfers that ride big waves, especially paddle surfers, make decisions constantly.” They learn how to use their fear to survive, “generating the confidence to be able to make big decisions at big times”.

The speed at which a surfer can paddle a surfboard limits the size of waves that can be caught in the traditional way—they simply can’t paddle fast enough. Big-wave surfboards need to be at least 10 ft long to maximise paddle speed and waves of 25–30 ft are regarded as the limit.

However, using jet skis and much shorter tow-surf boards, riders have been towed at speed on to the face of breakers approaching 50 ft. The tow-in method of catching waves proved a major point in 1998.

Big-wave paddle surfers from all over the world had gathered at Waimea Bay in Hawaii for an event known simply as the “Eddie”. More like a brotherhood than a competition, the Quiksilver Eddie Aikau Invitational is held in honour of a Hawaiian big-wave surfer who lost his life in 1978 going to help others in big seas. It is scheduled annually but only ever runs when the waves at Waimea Bay are more than 20 ft for a whole day. When such a forecast is made, invited surfers rush from wherever they are in the world to take part. It has been held only a few times in total—an indicator of just how rare swells of this size are.

In January 1998, the biggest swell ever recorded hit the Hawaiian Islands and the surf was so dangerous that the paddle event had to be cancelled. Projections from buoy measurements on that historic day predicted the breaking wave height at 44 ft, with faces of 88 ft. However, a small band of big-wave surfers couldn’t resist the opportunity the waves presented. They used jet skis to access giant waves breaking well out to sea, and towed each other with ski ropes into the biggest waves ever ridden.

That same year, New Zealand’s Rex von Huben, one of the earliest recognised big-wave surfers in the deep south, lost his life in a car crash. As a memorial to Rex, New Zealand’s first big-wave surfing event was organised by his widow Lorraine and good friend Kyle Davidson the following year. The Quiksilver Rex von Huben Big Wave Challenge was a purely paddle event with big cash prizes and 30 invitees, and the goal was to ride the biggest waves that could be found in the deep south over a two-week period. I was privileged to be involved, and recommended my old haunt of Centre Island (Rarotoka) as a venue.

A big day for most surfers is 6–8 ft, with some 10 ft rogue sets, but remote Rarotoka served up some 15 footers for the event, the biggest waves many of the surfers present had ridden in their lives.

In 1999, soon after the inaugural Big Wave Challenge, Papatowai was surfed by Todd Robertson. “I really didn’t know what proper big waves were until I paddled out for that first session at Papas,” recalls Young, who had travelled south with Robertson. “That was the turning point for me. It created the desire to chase big waves and to surf the biggest waves I could. Now we are paddling into those waves all the time.”

The “Rex” ran for four years, surfing Rarotoka each time, and in 2002, also at Papatowai. It captured the public imagination and nurtured big-wave surfers within a (relatively) safe context. The presence of a full rescue contingent enabled them to push themselves beyond their comfort zones and the keen ones began to invest in the correct equipment for such waves. A few focused their attention on tow-surfing.

Davidson was quick to recognise the potential of the jet ski. He and his tow partner Jamie Gordon started using one to access extreme locations where they took turns towing each other into the biggest waves they could find. Together they have become pioneers of big-wave tow-surfing in New Zealand, finding and riding many breaks for the first time.

Living in Dunedin, they have access to the most consistent big swells in New Zealand. While some may make forays to the deep south, this is their backyard, and their gutsy trial-and-error determination pushed open the door to a new era in big-wave riding and surf discovery in this country. Alone, they had to find out what equipment worked, where and when, and how to do it.

“Me and Kyle have been tow partners for about ten years now,” says Gordon. “We have a real good understanding. In the big stuff like Papatowai, you have to be able to trust the guy that’s towing you in or coming to get you.”

Says Davidson: “I’ve been on a wave and suddenly I’ve realised I’m in big trouble, and within a split second, instead of surfing, I’m sort of surfing for my life.”

Oscar Smith and Taane Tokona, both in their forties, began tow-surfing in 2004. “Visually it’s spectacular,” says Smith. “But close your eyes and listen, and feel the air pressures involved in that whole dynamic. It’s outrageous. The sound is like you are in a railway tunnel and suddenly a train comes in. Papatowai is more like a big echoing boom, while the Island, when that lip lands, it’s like a huge crack.”

Davidson and Gordon, Smith and Tokona are big-wave surfing pioneers, doing it all without sponsors. But corporate sponsorship has also played a part, with Hyundai sending Daniel Kereopa and Campbell Farrell to fly over some of Fiordland’s most exposed and previously inaccessible coastline, searching for the next big wave location. It is a big financial commitment, searching with no guarantee of a wave, but when the surf is pumping and there’s just the group of them out there, miles from shore with no one else around, apparently you just can’t beat it. I am still waiting to find out.

[Chapter Break]

Back in Dunedin it’s freezing. There was snow on the beach as I changed out of my wetsuit, and out in the surf, sleet was hitting my face so hard I had to protect my eyes with my elbow as I rode. On the drive home through the blizzard, my headlights lit a white lightshow of exploding fluffy flashes falling in a soft and silent flood, slowing me to a crawl and filling me at once with wonder: Why am I doing this?

In his book Breath, Tim Winton describes “the angelic relief of gliding out onto the shoulder of a wave in a mist of spray and adrenaline. Surviving is the strongest memory I have; the sense of having walked on water.” Perhaps aspiring to this impossible task of walking on water and the associated thrill of life reduced to a graceful dice with death is what drives all big-wave chasers.

Another set of onion rings rolls across the chart, throwing its fury all the way from Antarctica; what weatherman Jim Hickey calls a “polar rodent”. By Doug Young’s calculations, Papatowai will be breaking.

The drive down to Papas was windy and wet. There were no cars at the lookout, but the sun was beaming on a huge feathering peak that pitched and rumbled all the way through.

I scanned the break with binoculars; no one. Another set of giant waves lined up and rifled off as I ran down the hill. The boom met me halfway down. The waking beast was beckoning, taunting, teasing me. I watched and waited, but not a soul did I see.

It was like those wild empty days on Centre Island with no one to share it. I decided to wait for another time—it would have been foolhardy to paddle out there by myself. After months of waiting, I came, I saw, and I wandered home alone.

When I called Kyle Davidson later and described what I’d seen, he was gutted. “That’s the first time it’s broken this winter,” he said, a tremble of disappointment obvious in his voice. “It would have been a perfect little warm-up size.”