Return of the ancients

Sea turtles survived a meteor that killed the dinosaurs, millions of years of predator attacks, even the slow warming of the seas, only to be threatened by nylon fishing lines and plastic bags. Those that wash up in New Zealand almost always need the help of humans.

Sea turtles didn’t just survive the K-T extinction, they aced it. The turtles rode out the apocalyptic meteor strike that killed off the dinosaurs—and 90 per cent of life on Earth—65 million years ago by doing what they’ve always done: taking things slowly.

Sometime around the Middle Jurassic, about 170 million years ago, turtles had taken to the water. That, and their leisurely metabolism, turned out to be a winning strategy. They got by on the meagre pickings left to them, and went on to colonise most of the world’s tropical and warm temperate oceans.

Planet-pulverising asteroids they can deal with; plastic bags, however, might just be their undoing.

It seems a supermarket bag wafting in the current is, to a sea turtle, a dead ringer for a jellyfish, one of their favourite foods. Once inside, the bag impacts the digestive tract until the animal starves—unless it has the good fortune to end up in the care of Andrew Christie.

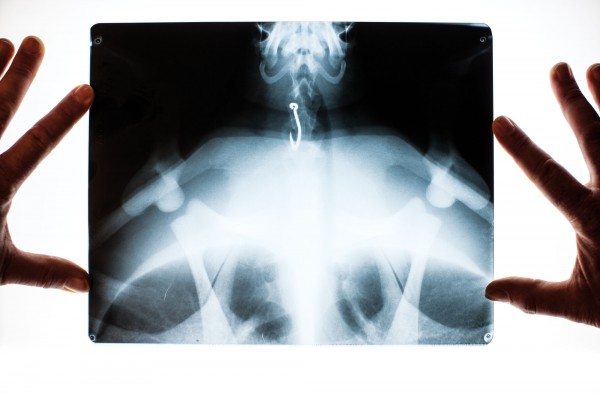

Curator of Kelly Tarlton’s Underwater World in Auckland, Christie tends an increasing number of sick and injured turtles. Some are full of plastic bags, fishing lines and other flotsam, while others have been run over by boats or snagged on fish hooks.

Others arrive exhausted, diseased, dehydrated, shocked by New Zealand winter waters, or otherwise ‘compromised’. They can take months to recover; some have taken two years. They need blood tests, antibiotics and intravenous drips, incubators, and specialised food. “When we get them, they’re pretty damn sick,” says Christie.

Once, he might have tended six injured turtles a year, but last year he had 21 patients, including greens, a hawksbill and an olive ridley turtle found at Houhora in the Far North. “As waters warm,” he says, “and the ocean becomes a less healthy environment, we get more and more.” So far this year, 12 turtles have ended up at Kelly Tarlton’s.

The first official New Zealand turtle sighting was in 1885, when a loggerhead turned up in Manukau Harbour, Auckland. By 1997, 138 individuals had been recorded. But recently, sightings and strandings have rocketed, in part, says Christie, simply because there are more people out on the water.

One of them is Dan Godoy. A Ph.D. student at the Massey University Coastal-Marine Research Group in Albany, Auckland, he’s been studying sea turtles for the past four years and has notched up 151 records, 65 of them green turtles. Since 1997, he’s collected 298 new and historical records of five species—mostly greens and leatherbacks.

“Yes, we’re seeing more turtles,” says Godoy, “but I couldn’t tell you whether that’s purely an artefact of increased awareness and observer effort, or a genuine expansion of their range.”

However, thermal images of the western Pacific offer a clue: every five years, the El Niño Southern Oscillation pushes warmer water against the east Australian coast. Each April, green turtle hatchlings scuttle down their natal beaches off the Great Barrier Reef. A lucky few make the relative safety of the open sea, where they catch the East Australian Current. Tepid with Coral Sea waters, the Current can race south at seven knots, eventually spinning into a giant gyre in the Tasman Sea. When a strong El Niño is brewing, that momentous conveyor belt delivers still-warmer water to the Tasman, to be picked up again by the East Auckland Current, which flows south-east past the eastern beaches of Northland, and further to East Cape.

In a typical summer, water in the East Auckland Current runs around 22ºC, but an El Niño simmers that to the point where tropical creatures start turning up in north-eastern New Zealand waters, feeling quite at home. The summer of 1988–89 saw just such a water-temperature spike, along with record numbers of sea turtles.

Some studies suggest that, as climate change gathers pace, those occasional influxes could become something of a norm. Most sea turtles are sighted here between January and April, although greens and leatherbacks can turn up anytime. Predictably, the bulk of records come from both coasts of the upper North Island, but strandings have happened as far south as Mason Bay, on Stewart Island, and as far east as the Chathams.

Because almost all of them involved sick or injured animals, says Godoy, the assumption has always been that they strayed here by accident. But he’s investigating the possibility that northern New Zealand is home to a local, if transient, population of green turtles.

After hatchlings flounder into the waves, they begin what researchers call their ‘lost years’, ranging the open oceans. “Nobody really knows where they go,” says Godoy, but he’d put money on convergence zones—where warm and cool waters combine.

“In the North Pacific, where those meet, you get a huge increase in productivity, and that’s where you find plenty of leatherbacks and loggerheads. It’ll be the same around the South Pacific—it just hasn’t been clearly identified yet.”

Young green turtles might sit in these oceanic gyres, foraging as opportunistic omnivores in the pelagic zone, until they reach 35 to 40 cm in length. Then they’ll settle into a suitable coastal habitat. With ample food and friendly temperatures, they might stay put for between 10 and 20 years, until they reach sexual maturity. Godoy suspects our northeastern waters might offer just such a sanctuary.

“While I accept that New Zealand is on the cusp of their preferred range, my research is showing a very different scenario to the waifs-and-strays theory. My data suggest they’re settling here—New Zealand is part of their natural habitat.”

Numbers are difficult to gauge, he says, but “we have more turtles than we think”.

“I’ve had 36 sightings this year. Mostly, I’m finding young green turtles, anywhere between six and 10 years old, that have most likely settled during favourable summers.” But he’s also found sub-adults close to maturity. “There’s obviously plenty of food for them, because they’ve been eating, and eating well.”

Many remain over winter, he says, but just how long they linger is unknown. “Ordinarily, they stay relatively local until they mature. It’s only then that they undertake their first adult migration back to their breeding grounds.”

He and Andrew Christie have tagged some of Kelly Tarlton’s recovered patients with GPS transmitters, then watched where they have travelled. Many were released near the Poor Knights Islands off the east coast of Northland, in warm, protected and well-stocked waters. They’ve survived for at least a year, until the transmitter failed, so, says Godoy, “the considerable effort that goes into rehabilitating these turtles is well worth it. And it’s shown us that they remain in New Zealand waters.”

But it implies a responsibility, too. All the marine turtle species in our waters are listed as either threatened or endangered—in the case of leatherback and hawksbill turtles, critically so. “So there will be more of a responsibility to manage the species, if we’re finding them more often.”

In 2000, an estimated 200,000 loggerheads and 50,000 leatherbacks died in longline fisheries worldwide. Kemp’s ridley turtles—a species that doesn’t visit New Zealand—are listed as one of the 12 most endangered creatures on the planet: since the 1940s, their numbers have plummeted from around 40,000 nesting females to just 500.

But protecting a highly migratory animal isn’t easy, says Godoy. Management must be coordinated between distant nations, but first, you need to find the source population—the genetic foundation—of the animals in your local waters.

There are several breeding populations of green turtles across the Pacific, and conservation managers like to treat them as discrete management units, so Godoy’s been taking DNA samples to try to determine the provenance of New Zealand’s stock.

He’s also trying to establish precisely what threats the turtles face during their time in New Zealand, and what needs they have. “For example, large, shallow bays with plenty of seagrass and other algae seem to be pretty important. That’s another reason why we should protect our harbours and nursery habitats from sedimentation and pollution.”

In 2010, Kelly Tarlton’s launched its Marine Wildlife Trust, specifically to treat sick and injured marine wildlife, and to foster education. “There’s still so little known about them in our waters,” says Christie, “but they’re turning up on our doorstep, and we have to look after them.”

If you find a beached turtle, he says, it needs your help. “A turtle shouldn’t be on a New Zealand beach, so it’s in trouble, and it needs emergency care. Treat it as you would a stranded whale: call the Department of Conservation hotline, and keep dogs away from it.”

And report any sightings, says Godoy. “We’re trying to build up a picture of marine turtles in New Zealand, so any reports of turtles, either swimming or stranded, are very important.”