Postcard from Samoa

Symbol of the warmth and charm of fa’a Samoa—the Samoan way—the gaily decorated communal pool is a focus of village life. As children frolic, its waters rinse away the grime of the day. Later, adults will seek out its coolness, washing together and talking as the sun sets. Yet beneath an apparently relaxed surface run troubling undercurrents, as Western ideas of individual freedoms challenge a rigid, traditional society where family and village are everything.

It was never going to be an easy interview. A palagi outsider is ill-placed to call a senior matai (chief) to account for 2500 years of tradition which, in this case, had seen his fono (council) banish a dozen families from the village. Their crime? Lawfully voting in the national elections for a candidate of their choice, but against council decree.

By chance, I’d already visited one exile: a woman who was clearly struggling through some kind of nervous breakdown. Ten kids, 40 years of loyal village service and Pow! Uprooted. Scattered. Overnight an Orwellian unperson in Arcadia.

I could still hear her words: “My family is split up. Sometimes I can hardly breathe. I feel as if my children have been torn away. All my life I have performed my obligations. I am on a support group for the hospital. My siapo [tapa] is used for displays. With my siapo I am the breadwinner for my family.” At the thought, tears filled her eyes. “To separate my family, this is like tearing my heart.”

As a journalist, I could not ignore this example of totalitarian intolerance within a society held as a paradigm of the relaxed and easygoing. I was determined to ask high chief Autagavaia Peni Lua the hard questions.

However, I knew that fa’a Samoa—the system of rules and traditions of Samoan life—runs on rails and hits anybody who gets in the way with the force of a locomotive. I was about to step on to the tracks.

As the chief approached, I reflected that there are two kinds of waddles in this world. The fat Labrador waddle and the muscle-bound pit-bull variety: the power waddle. At a hundred paces I could see he fell into the latter camp.

He wore a straw fedora jammed down over a bulldozer blade of a brow. His nostrils were broad and flared. A pair of ski sunglasses, their lenses a surreal pink, masked his eyes.

I rose from my seat to shake hands, a movement which caused the knot holding my lavalava to fall apart. I made a grab for the loose ends. A flicker of amusement played around the chief’s lips as he stood four-square, feet planted firmly on ground steeped in a 2500-year history of lavalava knot tying, not to mention 2500 years where a fono’s word was challenged on pain of death, and, on occasion, still is. It was also 2500 years that hadn’t seen much in the way of current affairs interviews.

There was a further impediment. In an unexpected turn of events, the matai title of Tupai had earlier been bestowed upon me as an expression of support for my investigations into fa’a Samoa. I had felt hugely honoured by this accolade, but it also compromised my role of tusitala, or storyteller. How could I critically examine fa’a Samoa when it had placed so much trust in me? I hoped Autagavaia Peni Lua was unaware of my status.

But, of course, as the high chief of one part of my new family, he knew all about it. Now he was formally welcoming me as a junior fellow. There was kindness and grave deliberation in his voice—a deep, powerful, soothing voice, which sounded like gravel being gargled in a throat full of whipped cream. “Tupai. You have been crowned! Tupai, son of Tuisafua! You are stepping up to be a master of the family with the other masters of the village and masters of the church. That is God’s authority, God’s authority being divided. You are now God’s representative in your village.”

Masters of the village maybe, but matai no longer select the national government. In the past two elections universal suffrage has allowed a revolutionary challenge to their power.

Matai like Autagavaia Peni Lua are fighting back. “I firmly believe that government law can never crush the village, and I feel these people [the banished families] were objecting to the voice of their masters. There are other villages where people have died for this. We have to crush the individual, otherwise how would you control the village?”

What would happen if the families went to court and lawfully returned to their homes?

“Then it is killing time.” Killing time for lawfully voting?

Some 15 years earlier, as a newspaper reporter, I had been assigned to cover the deportation of a Samoan mother, which would have separated her from her five New Zealand-born children—a decision that was eventually reversed for reasons of mercy. I mentioned the incident to Autagavaia Peni Lua. “That is New Zealand. This is Samoa!”

Back then I gained a personal insight into the lives of the 90,000 Samoans who have made New Zealand their home. I was impressed by the way this woman’s family so openly expressed their love for her. I was impressed by their unswerving dedication, over many years, to seeing that justice was done, and by the delicacy and grace with which family members related to each other, and to me, a total stranger. Without realising it, I had made my first contact with Fa’a Samoa—its warmth and welcome.

I was now forced to consider how little we know of these people who make up half of all the Pacific Islanders in New Zealand. As with other island groups, what we have is postcard knowledge. On one side there is white sand and palm trees, colourful dancing, church congregations and cricket. On the darker flipside is the label “South Auckland” and images of overstaying and the dole, machetes and rape.

Through social contact over the years I learned something of the complexities and contradictions of what it means to be Samoan—of the space that lies beyond the postcard. I discovered that veneration of Samoa and of Fa’a Samoa—with its tales of carefree days of pulling ripe fruit from trees, of spearing fish, of dance, prayer, church and family—didn’t square with one concrete fact: that more than half of all Western Samoans have chosen to make New Zealand their home. I wondered if there was more behind this exodus than simply economic opportunity.

Two months in Samoa provided some of the answer. I found that New Zealand, with its so-called unfeeling Western ways—so roundly condemned by many indigenous activists and palagi hangerson—offers a chance of liberation and emancipation from the dark side of the oldest and purest form of Polynesian culture: the stifling controls which deliver one of the highest suicide rates in the world.

Yet at the same time I discovered a richly dynamic society of great confidence and can-do competence, hinted at by the likes of Albert Wendt, April Ieremia, Lani Tupu, Greg Luganis, Mavis Rivers, Beatrice Faumuina, Peter and Rita Fatialofa, Jay Lagaia, Inga Tuigamala.

I found a society of great contradiction, where reverence is exceeded only by irreverence; a society where oppressive authority is facing an equally determined challenge from those who believe in their right to free expression. I found Samoa to be a complex drama of passion and pride, set on a stage of extraordinary beauty.

Even the trip in from the airport is magical. The road to Apia leads past a chain of extraordinary churches—fairytale castles of weathered grey masonry that seem to have been shipped here from the Middle Ages. Brightly lit Samoan fale—homes built without walls—float like Chinese lanterns among perfumed foliage. In Samoa, the cool of the night is the most important part of the day, and the streets and village greens are alive with people. I spy a child carrying a smoking coconut husk home from a neighbour. He had gone to borrow fire.

Apia is one of the few Pacific towns to retain a rusty-roofed, peeling-weatherboard Somerset Maughamishcharm. Sun-bleached buildings face the main promenade that leads around the half-moon of harbour or peer from lazy-blossomed shrubbery. The mountains beyond are razor-backed.

Samoans are a garrulous, hospitable, proud people. In the cafés, restaurants and bars it is seldom long before you are drawn into some fierce debate about something. They’ve earned their reputation as the Irish of the Pacific.

Setting the mood is The Samoan Observer. There’s no paper like it in the Pacific; no paper that takes such visceral glee in exposing hucksterism and pomposity and then dumping ridicule on top for good measure.

Sitting among the fragrant greenery of Aggie Grey’s hotel garden, reading the front page, I laugh out aloud. Today the Observer is giving hell to the minister of women’s affairs for his angry reaction to a reporter’s request for a manifesto:

Making a strangling motion with his hands, he shouted, “I just want to strangle you. You challenge us, you make war!”

Could it be, asked the Observer, that the minister, a former boxer, was in need of an anger management course? Had he suffered one punch too many?

This was standard fare. On politicians:

Stop stealing our money, you irresponsible, selfish demagogues!

This election should be declared a national disaster.

On Samoa’s principal church, the Congregational Christian Church, posting a $2.7 million profit:

You dare to call yourself religious men! Then stop building your hideous temples of dead concrete!

I have to meet the owner! I stroll up the waterfront, where New Zealand police once machine-gunned a peaceful independence demonstration. Sano Malifa is in his office, curled over his computer like a silver-maned old lion, pounding the keyboard with a massive paw and softly growling to himself. He is listening with half an ear to a cub reporter laboriously recounting her personal drama of tracking down some hot information. Her voice trails off as Sano points out that she is still a few facts shy of a story.

Like no New Zealand newspaper editor that ever was, Sano is a novelist, poet and businessman who spent four years in the United States doing a Kerouac On The Road odyssey before returning to Samoa, where he worked on The Samoa Times—though not for long. “The Times was virtually a vehicle for the richest and biggest guys in town, and their own little circle of power. So I started my own paper. We sold all we could print, and we printed stories no other paper would touch.”

In Samoa, such chutzpah carries a certain risk. In 1994, the Observer buildings were burned to the ground. Later, Sano was beaten up. “The fire was suspicious, but there was no question about the beating,” he says. “That was deliberate!”

“There is reluctance here to question and confront,” he explains. “When it happens, the old guard can get reallynasty. At the village level, many fono act like mini-politburos. Most of the members have no wider education. They have the idea that nothing outside the village matters. In the village, all you need is the plantation and the sea . . . and forget about tomorrow, because tomorrow will be the same as today.”

[Chapter Break]

Take a break from politics to sample Samoa’s tourism menu, which has helped revenue grow by 35 per cent in the past year. To accommodate visitors, Samoa offers everything from home-stay fale on dramatically beautiful beaches to Western-style hotel complexes. (Samoans delight in pointing out that one motel, Fesili’s, caters for every possible need since it shares a building with a raging karaoke bar, a shopping mall and a morgue.)

Legendary Aggie Grey’s is the flagship. Aggie, the quintessential Samoan matriarch, started the hotel almost 70 years ago. After her death at the age of 91, it was run by her family, and still is. Initially catering for whisky-sodden beachcombers, Aggie went on to make a fortune supplying American troops with hamburgers. Post war, the hotel became a haunt of film stars and celebrities. Marlon Brando—whose Godfather is a dead ringer for a matai—was a favourite guest. Today Aggie’s simply stands as one of the world’s nicest hotel experiences.

Despite Aggie Grey’s pioneering example, Samoa has been slow to promote itself as a tourist destination. One woman matai, Fa’asilifiti Moelagi Jackson, tells a story of Samoan priorities: “There was a plan for a $15 million mega-resort, but the paramount chief, he asked, ‘What can chiefs do there? We can speak no English. The girl in the next village, she can speak English, she’ll get a job—then what? She instruct me to go pick horseshit in a basket? That’s all I can do in this new hotel.” It didn’t happen. The fifteen million went to Fiji.

As a confirmed fan of Samoa, I’m glad it did. Instead of foreign ownership, it is the villagers in both main islands who control things, and they’ve taken to small-scale tourism with gusto. It is the lack of development that gives Samoa its advantage.

I cross the island of ‘Upolu to take a village tour through a watery wilderness of coastal jungle. Palu Ta’ase, a grave, lean old man with deliberate Oxford English, greets us. “We are very proud you are here to publish our small undertaking. For the tourists we supply a small sandwich and a tea. For you we have some French toast.

“We see the eco-tours at the hotel and we think, why is that we can’t? We see a newspaper to make an advertising. In this village we want to go up, not down. Every face here is turned to the sun! We love this very much. We can all get involved.” Some women are scooping sand into buckets in the blazing heat and carting it 200 metres to beautify the new visitors’ area.

Soon we are paddled in an outrigger up a Samoan Limpopo. There is a deep coolness under the canopy of 15-metre trees. A heron flaps through branches that trail orchid-like vines.

Corridors of vision open up where the main stream meanders off into the fastness of the swamp. In one bayou the water boils with fish. In the shallows the river bed of clear white sand is tiled with leaves from the overhanging trees. A heavy rain plops from the sky. I slip from the canoe into the river and let the current take me.

Back at the centre a mug of cocoa is waiting, and so is more leisurely conversation. We talk about why Palu’s family left this place for the drear cold of Hutt Valley.

“Most of our people are away in New Zealand and Australia and America because the land of Samoa can give only a living but not money,” he says. “Our country is very peaceful, but very poor. God put everything here: the food plants, the medicines—we fully believe this. But there is no gold. There is no ore in our soils.”

Peaceful now, but what about New Zealand’s suppression of independence earlier this century?

“Oh yes, the New Zealand soldiers chase us like pigs in the forest, but we are not looking back. Friends do not look back to such things. I don’t wish to discuss these times with you.”

The record is plain enough about one of the more shameful periods of New Zealand history: our brutal and incompetent administration of Samoa, which in 1914 we seized from the Germans. The archipelago, in a colonial carve-up, had earlier been divided between Germany and America.

Barely four years after New Zealand planted its flag the administration allowed a sailing ship carrying influenza to land. In the following months 8500 Samoans died—almost a quarter of the population. The United Nations later described as one of the most disastrous epidemics of this century. Streets were filled with corpses. Whole families died together. But the Samoans were left to fend for themselves, with the few doctors mostly restricted to caring for whites.

Rather than admit inadequacy, the administration refused an American offer of a fully equipped medical team ready to sail from neighbouring Pago Pago. New Zealand never did send any assistance. A request for food from a missionary boarding school where 150 girls lay ill met a fairly typical response from the administrator: “Send them food? I would rather see them burning in Hell. There is a dead horse at your gate—let them eat that! The great, fat, lazy loafing creatures.” (This isn’t some bizarre apocryphal tale: it was recorded by the principal, Elizabeth Moore.)

This style of administration continued through the 1920s, with matai having their titles stripped for such trivia as planting a hibiscus tree out of place. New Zealand tried to crush village structure. Long remembered was the new administrator’s refusal to allow a doctor, accompanying him on a village tour, to attend a mother dangerously ill in childbirth. Schedule did not permit. Mother and child died.

In Pago Pago, U.S. administrators worked in a rough form of partnership with Fa’a Samoa, but in Western Samoa requests for fair treatment saw a raft of repressive legislation that turned the place into our own little gulag archipelago. The Samoan response, eventually, was the independence movement called the Mau.

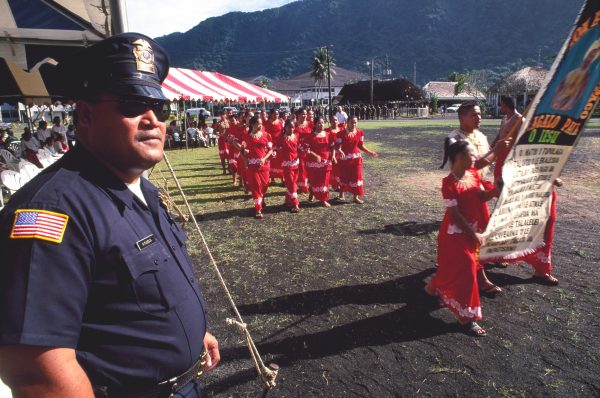

In 1927, it embarked on a disciplined campaign of passive resistance that would have done Gandhi or Te Whiti proud. In 1928, New Zealand sent the navy, which immediately arrested 400 marchers, then discovered there was nowhere to put them. A further 150 Mau presented themselves, demanding to be arrested.

By 1929, hundreds of Mau, all decked out in purple lavalava, had taken to regular marches around Apia. At one march scuffling broke out when police tried to make two arrests for non-payment of taxes. New Zealand police opened fire on the crowd with machine-gun, pistol and rifle. The leader of the Mau turned to face his confused people, urging them to move away. He was shot in the back. His dying words were: “My blood has been spilt for Samoa. I am proud to give it. Do not dream of avenging it, as it was spilled in maintaining peace.” Seven others died.

The police used their own overreaction as justification for further violence, to crush the Mau, who fled to the bush. In the weeks of the hunt, two unarmed boys were shot dead, one after collapsing in exhaustion. But with the Mau refusing to surrender, and facing non-co-operation from villagers—and, crucially, with New Zealand seamen refusing to crew on re-supply ships—the military operation was declared a failure. A truce of sorts was arrived at, and, eventually, with the arrival of the Labour government, New Zealand made concessions. (It is a stirring and dramatic tale first traversed at any length by Michael Field in his must-read book, Mau.)

I’d assumed Samoans would have been proud of this history, but I encountered a general reluctance to discuss the Mau. It is understandable that people should not wish to reopen the wound for every passing New Zealander. But I also realised that, when the smallest village slight has the half-life of uranium, to hail the Mau as heroes is to impugn the honour of families that, for whatever reason, supported New Zealand. In this way Samoans acknowledge the complexity of that period, in revealing contrast to some Maori revisions of history, which try to sell the message that all stood firm against the crown. New Zealand has now thoughtfully offered to fund the restoration of the Mau headquarters.

The German period, with its orderly and effective administration, is remembered with fondness. This preference translated into the post-Mau establishment of a Samoan Nazi party, resident Germans leading the move. For Samoans there was the slight problem of establishing Aryan credentials, a thesis of wishful scholarship being posted off to Berlin. But that didn’t prevent swastikas being hoisted over Apia, the design even being incorporated in tattoo. Hitler Youth established a Samoan subbranch. Children were named Hitila, and still are. One Samoan, no doubt reflecting a strand of contemporary German thought, told me that Hitler has been misunderstood. “He did a lot for Germany, built the country up.”

Er, didn’t he take a wrong turn somewhere?

There is no shortage of surprise in Samoa. I become a regular at the MADD gallery (Music Arts Drama and Dance). A sagging, crumbling mansion with floors that shudder underfoot, the gallery and cafe is run by an artist/writer who rejoices in the name Malietoa Mamoe Von Reiche. Her father is the Head of State.

Mamoe’s mission is to provide a venue for free expression. This is no easy task in a society where a playwright was once roundly condemned for setting Romeo and Juliet in Apia with a cast of Samoan characters—”We are not going to have this Shakespeare palagi cheapening Fa’a Samoa!”—but Mamoe is undaunted.

The goal of free expression might be possible in Apia, but in the villages? The villages are like a different country. I read in one poem at the gallery the thought that village life is like being locked up in a glass jar with little holes in its lid, just enough to breathe.

Today in the cafe Mamoe is serving a chilled asparagus soup, followed by chilli fish stew with fresh coconut cream, rosemary, basil, mint and garlic.

“Quick! Come and get it before your soup gets warm!” she calls. This wordplay—from a woman who plays bilingual Scrabble—is not unusual among Samoans, for whom verbal chess is a favourite pastime. They are always milking every least statement or interaction to ambush you with some unexpected tangent of humour or meaning.

(Mamoe’s daughter, Sela, has begun a tuna export business. She’s called it Albacorp.)

Samoan speech is a sugary, dreamy music of cadence and inflection, where a single word is teased out to occupy the same space we give to a whole sentence. It is a vowel-rich language, the sonorous sounds easing from the tongue. English, bristling with consonants, seems to Samoans an ugly stop-go language.

“Your words are crunchy, you have to bite them off—they have bones in them!” a friend tells me.

[Chapter Break]

Weeks pass, and I am still in Apia. Every night there seems to be a new show, exhibition or play. Lending a special energy are the fa’afafine, transsexuals who, in Samoa, are not seen as men in drag but as quasi-women who openly partner heterosexual males.

Although they are accepted within the family, a son turning fa’afafine is not exactly welcomed. Their family role can mature into that of favoured aunties, but many are relegated to Cinderella drudgery. Pairing off with village men does not offer much of a future either. Their special status as performers and entertainers is the route to emancipation.

One, Cindi, turns on an experimental stage show that ranges from lip-synched Tina Turner to slow, sensuous hula, to ballet, to a kind of martial arts slap dance fusion, to showtime Bing Crosby tap-dancing. On another night, I see an even more extraordinary routine, to the music of Bolly Sagoo, a sitar-playing rapster from Delhi. The Samoan—performers decked out in saris, bejewelled turbans and loin cloths—weave an extraordinary mix of classic

Indian dance and traditional Samoan to this wailing Indian rap.

After the show the crowd spills out on to the seawall, where it seems half of Apia gathers every night for the cool sea breeze. Past midnight, while we talk, thin boned children softly remove beer bottles as they are emptied. Young men ride the trays of utes, like charioteers, heading off to any one of a dozen sauna-humid nightclubs. A canoe slips out from the river to fish, its lantern glowing.

I comment on how brightly the stars shine. “That’s you to blame, palagi! You take away all the ozone. You made the hole, you patch it up!”

A police van stops. One of the officers is scolded by a member of our group. “How dare you speak to me when everybody knows what your grandfather was!” In Samoa, memory is a potent weapon.

One friend tells me: “This place is too small. You smell the flowers in my hair) See how the perfume travels so far at night, so quickly. That is how news travels here in Samoa. Should I decide to elope with my lover tonight, when I get to where I am going, my family will already be there!”

East of Apia, it is not long before the coastal plain is shouldered aside by mountains. Here surf pounds at long, deserted black-sand beaches, but in the bays village life resumes. From a headland, photographer Arno Gasteiger and I look down on a village where the fale are hot pink with blue trim. The glossy green hillside is tossing and shimmering with the wind and sun. I think of New Zealand servicemen hunting down the Mau.

These villages are not just clean, they seem groomed and scrubbed and combed and plucked. Closer inspection shows the gravel is combed. The road edge is marked by whitewashed boulders. Alongside are plants so luridly shot with colour that they’d be considered rejects at an artificial plant factory. Crazed whippet-thin curs lurk catatonically in the shadows.

We stop at a bathing pool which dams a mountain stream. It is decorated with floral displays of hibiscus blossoms individually threaded on the spines of coconut fronds. The stonework of the pool is painted sky blue, with the pointing picked out in white. At times like these it seems as if centuries of care and attention have transformed Samoa into one giant exquisite botanical garden.

Downstream, under an archway of floppy-leafed breadfruit trees, a young woman is doing her washing with a bright pink bar of laundry soap. A baby boy plops on to her lap. She soaps his body. He dives through the pure mountain water, leaving a trail of lather.

Someone else arrives with a box of Sudso powder (which, weirdly, is endorsed on television by a rather sheepish Sean Fitzpatrick). A child pushes a toy wheelbarrow made of sticks with a plastic net float for the wheel.

At sea an outrigger eases by A group of women stroll to the beach carrying a net. They have fabric bound around their heads to protect against the heat. They are hunting igaga, Samoan for inanga or whitebait. (For what perverse reason the missionaries dropped the n from the Samoan dictionary—when igaga is said “inganga” and palagi is said “palangi”—is anybody’s guess.) The women form a circle, and one splashes and rushes toward it to drive the fish into the nets. She uses this movement as an opportunity to perform some outrageous jester’s dance, saying God knows what about the palagi on shore.

My suspicions are not without foundation. The Samoans are masters of merciless eye-jabbing Basil Fawlty wit mixed with a cheerful Chaucerian lewdness and a Benny Hill eye for endless double entendre. The love of outrageous irreverence is shown by the way the principal Samoan swear word, aikae!—eat shit!—falls from the most delicate of lips.

We drive on, past Don Quixote horses drooping in the heat. On the steps of a church a Cinderella fa’afafine mops the flagstones. We stop for a soft drink. There is a magisterial height to shop counters in Samoa, which children approach like a prisoner approaching the dock, whispering their mother’s order for 50 sene of laundry soap and two cigarettes. Whap! The change slaps down on the counter.

We turn off the main sealed road that leads around the island and cross a bridge built over the lip of a waterfall formed where a great green river pours 50 metres directly into an inner reach of the sea. The mountain peaks are lost in cloud. For several hours we grind along a four-wheel-drive track. There’s the feel of the Ureweras, of tropical Tuhoe country.

We pass through the tiny village of Lona, backed by cliffs that rise a thousand metres sheer from the sea, mist hanging heavily at their brow. Centre-stage in the village square lies the burnt-out chassis of a bus, like the skeleton of some large animal. I am reminded of a massacre I reported in New Caledonia, where eight villagers were ambushed and their utes torched. Their crime was to seek independence from the French. Here in Lona the blackened bus carcass is also about the price of defiance.

In 1993, Nuutai Mafulu, a Samoan recently returned from New Zealand, was shot dead in front of his family for defying the fono on some trivial matter, and all his possessions were burned, including this bus. It doesn’t pay to mess with the fono in any village, least of all when you’ve just returned from New Zealand with a pocket full of money and a head full of modern ideas. For that matter, authority in any country is at its most dangerous when it is ignored.

But in Samoan villages it is sometimes hard to discern any sense of proportion or restraint. Tariu Tavaiti was another returnee who, in 1980, tested those particular waters in a less isolated village. Using his savings from New Zealand, he became a successful businessman and bus operator, but for refusing to attend church the fono banished him and his family from the village, and imposed a boycott on his buses.

Tavaiti won a court ruling that stated that the banishment was illegal. The fono responded with fresh threats of violence if Tavaiti or his family attempted to return to the village. It redoubled the bus boycott, with threats of even harsher punishment to those who broke it. The police were warned not to set foot in the village.

A fono defending its digpity is like a cornered animal. “Whenever push comes to shove,” someone tells me, “if the village doesn’t want it, it doesn’t happen. Everything at village level is taken care of by the fono. I mean, there is no army—are you going to send in a handful of unarmed police into a village where everybody has a bushknife in one hand and a rock in the other?”

While all this was going on, one matai, Nanai Likisone, made the near-fatal error of breaking the boycott by catching the wrong bus. Untitled men were sent to Likisone’s house, where they bound and trussed him like a pig, with a stick through his legs and arms. They dragged him along the road to the waiting fono, where fires for a man-sized umu had already been lit. Only the intervention of the village pastor, who threw himself across the man’s body, saved him.

At Lona, our guide suggests we don’t stop near the bus. Since the killing, the villagers have been sensitive to rubbernecking outsiders. It is a matter of embarrassment. There is not the slightest suggestion of personal danger, but on leaving the village I can almost hear the opening chords from a Deliverance banjo.

We pass further villages, and the mood wanes. At the end of the road we leave the vehicle and walk for several miles along a beach strewn with black boulders of Henry Moore voluptuousness. We return to find our 4WD wagon has disappeared. Our guide is certain it will be back. Presently a grind of gears announces its return. The local pastor had taken it for a drive. The pastor calls from the window, “Ohhhh . . . I just had to go to the next willage! Are you hungry? Are you thirsty?”

Waiting for the food—barracuda in coconut milk—I watch a cricket game, where the fielding involves diving into the sea to retrieve the ball or stampeding through someone’s backyard. A kid settles down beside me.

“A-mare-i-cah is my name. Watisyrrrname?” America touches my white skin.

I see a child running along the road, fluttering her hands, a crazy zig-zagging darting run. The little blighter appears demented. Then I see that she is flying in tight formation with an oblivious dragonfly.

In this wildly isolated place two name-tagged Mormons pass us, a picture of starched white rectitude—I wonder at their sweaty persistence.

As with all things here, the Samoan relationship with the church is more complex than it seems. Although the missionaries imported their own set of puritanical rules, the popular idea that these were forced on a carefree people doesn’t survive an examination of pre-Christian Polynesian religions, which featured an endless catalogue of sins and a vengeful pantheon to offend—with immediate and brutal punishments to match. The missionaries, as they did in New Zealand, offered a kinder, forgiving God—which is one reason the message spread so rapidly.

In typical Samoan fashion, the arrival of the first missionary was not seen as having anything to do with Europe, or even the Christian faith. Nafanua, the Samoan she-god—a sort of Xena—had foreseen his coming, and missionaries were given a Samoan identity as sisters, or peacemakers.

The title related to a traditional social function performed by Samoan women: that of mediating in disputes. Fa’asilifiti Moelagi Jackson explains. “Very important was the peacemaker’s house of the old ladies—where the old ladies sit chattering like typewriters! Before, if a man hits a woman, that’s where she dives for, and he won’t come after. If the children are in trouble, that’s where they go. This house was crushed by the missionaries, who took the title but did not trouble themselves with the responsibilities. Now the pastor hiding in his high-rise palace is very remote to the people. They do not feel comfortable to dive into that house for help.”

Villagers today are sincere in their faith, but few are under any illusions about the nature of the mainstream Protestant churches—the churches established by the missionaries—and their pastors. One matai observes: “The pastor is just another fat man asking for money. Every second year some pastor is running off with church funds, and we find he has bought five houses in Auckland—but nothing ever happens. And pastors in New Zealand are even worse! They are like little kings because life there is centred on the church and not the village. There is no balance between the church and the fono.”

Not surprisingly, pastor-hood is a sought-after career. With free home, free furnishings, free education, an annual refurbishing of the house, and cash, it’s a package worth up to $40,000 a year, or at least ten times the average income of the flock from which it is exacted. In raising this money the churches have deliberately harnessed the traditional rivalry between villages to maximise gift-making, exhorting each village to give more than their neighbour as a matter of honour—with villages even going into debt to provide the most lavish gifts to the pastor.

Despite near universal grumblings, there is little direct challenge from the congregations, but many are making the silent protest of moving to other faiths. Some 5000, including the head of state, have become B’hai. A B’hai temple, all swooping Brasilia-style concrete, looms from a hillside on the cross-island road. There I fall into conversation with a middle-aged woman. “The [Christian] pastors—every second word is about God, but every first word is about giving money! I became so confused. So I look around for the most logical faith. I decide I don’t like the way the Catholic priest expects you to kiss his ring. The Mormons? They are like the Reader’s Digest—they keep coming back when you didn’t order anything! What I like about B’hai is there are no clergy, no money to give to clergy. You give if you want to.”

The Mormon church presents the biggest competition to the mainstream churches. In even the smallest of villages, temples are built in the manner of a McDonald’s franchise, according to a plan provided by head office back in Salt Lake City. Samoa gets the Tropic C plan. These immaculate buildings, with their bland, featureless architecture, stand out in flower-filled villages as citadels of suburban colourlessness.

Only the main temple in Apia, with a gilt angel poised tip-toe on the spire, makes any reference to the business at hand. But even here there is something smug and impermeable about the architecture, and enormous, non-pearly gates guard the way into the gardens beyond. I could never quite steel myself to knock on a door to chat about the faith.

Some 30 per cent of Samoa has converted to Mormonism (45 per cent for Tonga), with many emigrating to Utah.

The conversions are not difficult to understand. Given the choice of being hectored and bullied by some hellfire and brimstone pastor or cycling up a few hills in a far-off land—with the promise of a residence permit for America—I’d be strapping on a name tag. For that matter, even the Holy Gospel Snake-Handling Amen Church of Eternal Redemption Forevermore is a more rational alternative to the traditional pastor with his demands for money.

Several times in Apia I had heard the electric guitar and Full Gospel honky tonk piano of such a church drifting through the torpor of a Sunday afternoon. I’d driven around looking for it, but, maddeningly, could never hit the right street.

It was only later, on Savai`i, that I finally got to attend a Full Gospel service. Joel Anae, with an “I love Jesus” shirt protector in his pocket, had brought the Full Gospel gospel from Dallas, Texas. His kid brother, with ginger high in his hair, had a diamond set into one tooth and wore snakeskin cowboy boots. Together they spoke an ersatz Southern drawl.

A sweet old grannie, with hair swept up in a bun, shook my hand. Her skin was as soft and dimpled as the skin on a glass of warm milk. But her other hand wielded a gawgucking stick. With the service under way, she proceeded to stalk miscreant children. It was not long before some child mid-pew got a crack across the head. Although this was an altogether friendlier style of service, the old woman with the stick is one feature of the regular church the Full Gospelliers have not dropped.

The singing, when it came, was a strangely powerful Whitney Houston/Samoan gospel mix that soon yielded to that deep Southern groaning bray I’d heard so often back in Apia—as if Blind Lemon Jefferson hisself was in the flock. Soon emotion and energy overwhelmed actual music, and the hall was filled with helter skelter prayer in murmuring tongues, something like a roomful of auctioneers on different doses of Prozac—”godinpowerpraisehallyloolahholyghosttheloveofgod . . .”

Joel snapped the flock out of whatever they were in with a sermon that was accompanied by electric guitar riffs, rather like a Jerry Seinfeld programme. “Gathered to‑gether today dwanga,

dwanga, dwing—in the eyes of the Lord . . .”

I kept a weather eye out for gran, in case I got a stick across my knuckles for writing in church. Next minute, some other woman had me by the hand and was leading me to the altar. Was I now going to be installed as a Full Gospel deacon?

As I walked up the aisle I had the sense of my lavalavaabout to disintegrate around me. I pushed my belly forward to hold the knot tight.

I was introduced as a friend and asked to share a thought. I mumbled something about how pleasing it was to see so many happy people, and, clutching my lava about me, scurried back to the seat. With gran guarding the door there was no escape. I sat for several hours listening to Full Gospel children reciting Scripture in a Walton family singsong on this tiny island in the middle of the Pacific.

[Chapter break]

One day Arno and I mount an expedition to the crater lake of Mt Lanoto`o, which the guidebook promises glitters with goldfish. The highlands of ‘Up°lu are mysterious country—a kind of savannah grassland with amputee trees like telephone poles dotted through it, each one festooned with Marge Simpson beehive plumes of creeper.

On the flanks of Mt Lanoto`o, mixed in with the forest is heavy saw-toothed elephant grass, booby trapped with leeches and nettles that madden the skin of the legs. It is like being set down in deepest Africa. Any second, I expect to see Katherine Hepburn staggering by, tearing leeches from her bodice, with a portered grand piano bringing up the rear.

Somehow we find ourselves bush-crashing up a blind gulch, into a humid hell of slippery rocks, me in ankle-snapping jandals. I am alternately garotted by vines and ambushed by pitfalls of rotten logs, while Arno with his long legs dances on ahead. I discover a shallow trickle of water. I flop into it like a farm dog dropping into a puddle.

We hear a burst of manic laughter and a wild catcall in Samoan. To me this is reassuring, but I wonder at the bravery of the early missionaries. In a clearing we find foresters who are planting a water catchment. A pot is swung from a log and a stew is bubbling. The men offer us a drink. We learn that they spend three months in the bush for $35 a week.

They point the way to the summit. Way below is Apia, and a chrome-blue sea beyond. A flight of doves threads through the rainforest. Three flying foxes ride the thermals like hang-gliders. The lake and its goldfish don’t disappoint. I breaststroke out into a jade-green lens of water, surface of which is as clear and convex as the surface of an eyeball.

The sighting of the foxes is a lucky one. Samoa has two species, but only one is active during the day. They used to crowd the skies, fighting and squealing for position on the mango and breadfruit trees, but cyclones have virtually eliminated them. Some were killed outright, while others starved because the trees and insects were destroyed, or, worse, were killed by villagers and dogs and cats for food as they rummaged for fallen fruit on the ground.

They were already under pressure. Between 1981 and 1986, some 30,000 carcasses were exported for human consumption to Guam, where the flying fox had been wiped out by the Australian tree snake. This despite the trade being illegal, and there being a hunting ban. Investigations have now shown that some 30 per cent of primary rainforest may depend on bats for pollination, with up to 80 per cent of seed dispersal accomplished by bats.

I knew none of this as I bathed. I learned the details from an inflight magazine on my way home. I also lifted the following facts about the Samoan art of tattoo. “When a baby is born in Samoa, its grandmother will start weaving a mat as a dowry . . . but when the baby is a boy the grandmother will start collecting the soot from burning candle-nut to make dye for tattoo. Tools for a tufuga will be passed down through generations. Designs include starfish, canoe prows, fishing nets and the rafters of a roof . . .”

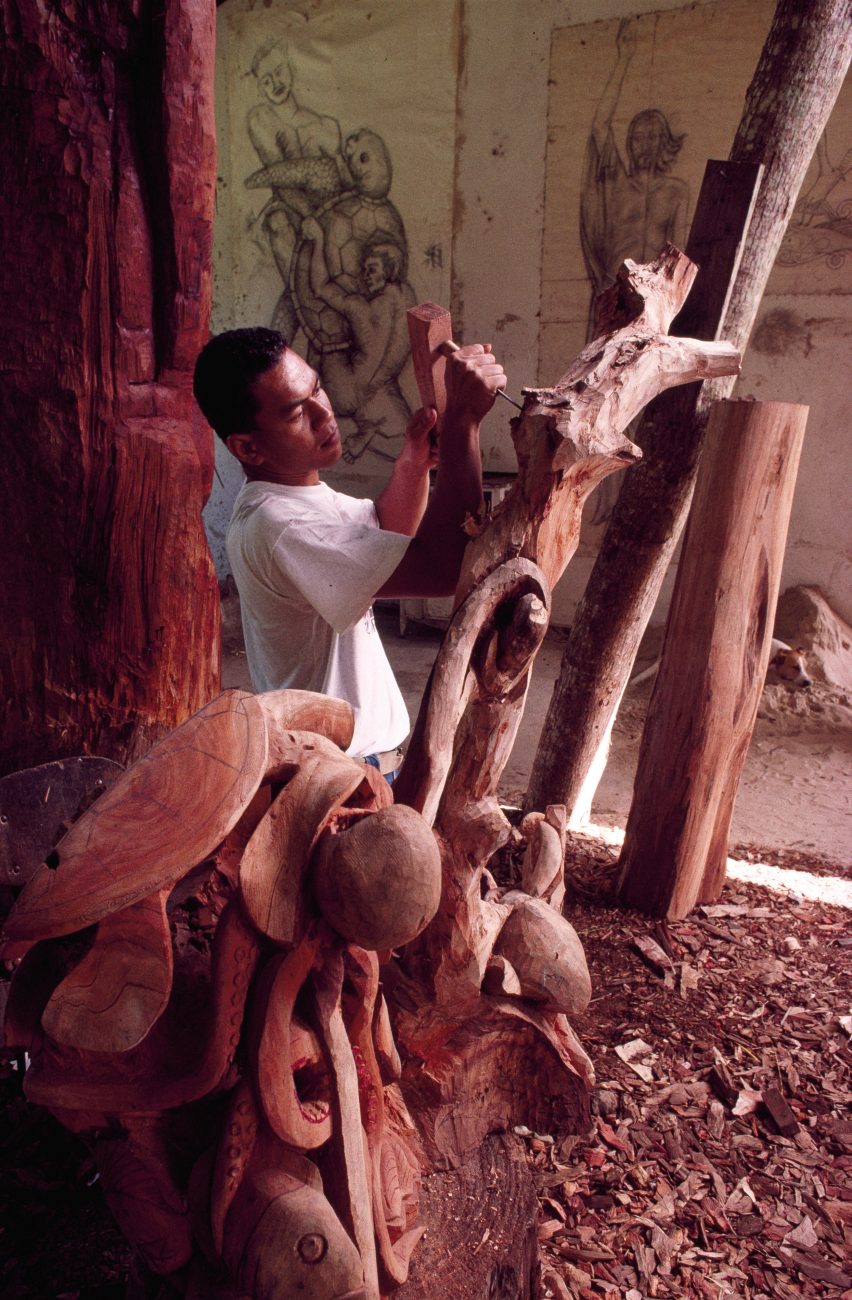

I wasn’t in receipt of this information when I visited master tufuga Sualuape Petelo to observe the craft that was once common throughout the Pacific, but has only survived without interruption in Samoa. Away from the coast, in the still steamy air of the interior plantations, we found him inscribing a young woman’s legs. Heard the tap tap tap of the stick across the head of his adzes, which are packed in a box faced with marbled Seratone. Each year Sua makes several trips to the States, earning big money from the 40,000 strong Samoan community there.

The woman is having a fine tracery of design applied from knee to hip. To relieve the pain she takes her hair in her hands and winds tight. The limbs of the woman, of the tufuga and of his apprentices are woven together.

Sua cantilevers the serrated rake out from his left hand. To help control the strike the shaft is held in tension by the thumb. It takes three to four blows for each incision. The blade returns to the razor-thin line without deviation, even though the skin is obscured by a puddle of ink—which these days is made from the soot of a kerosene lamp.

Apprentices carefully stretch the skin tight to receive the incisions. In the way of apprenticeship, this is a thankless but vital task. If the skin is not stretched evenly the line will stray off course.

Another apprentice attends to Sualuape’s nicotine needs, inserting lit cigarettes into his mouth as required and scooping ash from its end when told to, and not before. At one point I see him anxiously watching as the ash teeters at critical mass, an anxiety shared by all in the room.

Tattoo is a tense enough exercise as it is. Any error will reflect badly on the honour of all involved. I marvel at howso few of the incisions produce blood when this man is tapping a chisel into trampolining skin through a puddle of ink, and when only millimetres separate carving from cut—yet every time the puddle of ink is wiped clear, perfection is revealed.

The survival and strength of Samoa’s culture isn’t just attractive to tourists. Anthropologists, for one, love highly structured societies like Samoa because they allow them to fill books with complex diagrams and spend years in tropical climes. Above all, they feel instinctively at home in a society ruled by a rigid pecking order with all manner of snits and quarrels about status. It reminds them so much of university life.

Just look at the storm of protest that broke when Margaret Mead’s seminal study of adolescence in Samoa was conclusively debunked by a New Zealander, Derek Freedman, in 1983. Back in 1928, Mead had successfully sold to the academics a story that Samoa—despite its rigidly observed customs—was a haven of free love, with little violence or rivalry and no emotional or psychological hang-ups. No one questioned this absurdly utopian vision. They were all too busy booking tickets.

As Lelei Lelaulu, the editor of a New York newspaper, wrote in the Dominion: “My own coming of age in Samoa seems to have been spent under coconut trees being interviewed by anthropologists!”

It’s quite extraordinary that the postcard myth of peace and plenty given academic credence by Mead survived for so long. The credulity comes from a powerful need in industrialised countries for there to be some unspoiled Arcadia somewhere. We want to believe that the postcard has only one side.

So Samoans must now endure a succession of paradise-seeking backpacker types who lecture about the evils of the 20th century. Theirs is the arrogant view that Samoans pursuing more material wealth and more individual freedom are making a fundamental mistake—are destroying the balance and beauty of their traditions.

As if Samoans have no business being exposed to new ideas or a world view, the paradise-seekers are particularly hot on the arrival of television, which is proving a key agent of positive challenge. I saw one episode of Dr Quinn Medicine Woman in which the townsfolk were divided about some new teacher whupping the kids. Trite and saccharine it certainly was, but here were kids intelligently challenging teachers and parents being swayed by Dr Quinn’s plea not to confuse fear with respect. For village Samoans, this was a parable of heretical import. In no shape or form, not inside a month of Sundays, would these ideas have been discussed within a family, or been aired at village level, any other way.

[Chapter Break]

The tiny island of Apolima is a Lilliputian volcano that pops like a cork from the straits that separate Savai`i from Upolu. Home to 150 villagers, it has one of the most dangerous harbour entrances in all of the Pacific: a narrow dogleg gut in the rock that is overwhelmed by surf in all but the mildest of conditions.

We hitch a ride there on a fishing boat. The pastor’s wife is a fellow passenger. She has a bag full of iced Pepsi, and is transporting the precious luxury of chilled bubbles to an island with neither power nor a store. She offers me a drink. “You coming to my island? Welcome to my island!”

Soon Apolima looms through the spray, a gaunt rock fortress of cliff and breakers. We follow the cliff-line, keeping just out from the surge of backwash. We pass a headland, and the village of Apolima is revealed, laid out in a horseshoe around a crater that opens at one end to the sea. We nose into a rush of foam and spray that spills from the reef blocking the entrance. A pause in the waves shows there to be a channel the width of a suburban driveway. Heavy seas close behind us, leaving no sign of our passage. There is something biblical about it.

The high chief welcomes us to his fale. The only furniture is a wardrobe made of coconut timber and decorated with faded Coke stickers. Stored in the rafters are a dozen fine mats, so named for the delicacy of their weave that gives the fabric the feel and sheen of silk. Some mats are hundreds of years old. All have a genealogy of their own which traces when they were exchanged as gifts with whom and for what reason. In this way the mats are repositories of social history. Like scrolls; a family album. During one period of their history, all across Samoa these mats had to be hidden in the bush—a New Zealand administrator had decided to ban them. Making them was a waste of time, apparently.

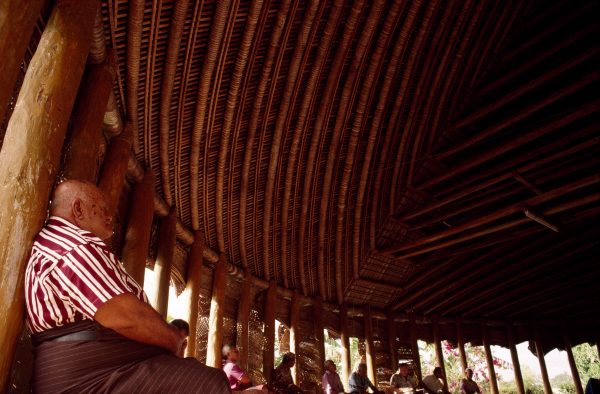

Lying on the cool of the polished concrete floor, I cast an eye over the woven circular structure of the fale. It’s like living inside a cane chair. There are no walls. Instead, solid posts support a roof framework of raw limbs that fit each other with an assortment of boat-builders’ joints.

The thatch is woven coconut lashed to split timber laths. There are no nails. Everything is bound together with coconut fibre. For privacy and protection against wind and sun there are coconut frond drop sheets which can be unrolled as required.

The fale is on a high point overlooking the village that I am aching to explore. I stroll down to watch the fishermen preparing their boats for the evening expedition. A family of sun-blackened spare-framed adolescents stows a boat with bait, an enamel pot of fish stew, a lantern and a pot of cold tea.

A younger boy, maybe four years old, slips the stern line from a post on shore. The boat slips gently toward the gut, tosses on the swell, straightens up under power and makes for open sea. No word has been spoken. An older man calls the little boy out to the reef, bucks him up on to his shoulders and takes him for a quiet saunter through the waters of the bay. Out by the headland the swell explodes on the cliff-face. Against the rainforest flanks of distant Savai`i, plumes of spray rise from the awe-inspiring Taga blowholes like whale spouts.

I help to launch the remaining boats—heavy outboard-powered six-metre ply catamarans—down a series of driftwood rollers. I don’t know to stand clear of these rollers, and the weight of one boat flicks a log up to hit me painfully on the shin.

In the way of a child demonstrating competence while at the same time mashing a thumb with Father’s hammer, I keep a poker face. This is not successful. For one thing, a dozen eyes have been keeping a careful lookout for this kind of thing. For another, the bit of wood actually makes a loud noise on the shin.

There is a twinkle in the eyes of the fishermen, an exchange of glances. They leave me a drinking nut from the store they had stowed for the night fishing. I watch them disappear out to sea. Soon the island and the canoes are lost behind a picket of rain that drives down the strait, coming from nowhere and going nowhere.

I sprawl on the mown grassy banks of a brook that flows through the village. Its source is a champagne spring on the rim of the crater, and several pools have been made along its course, some for bathing, others for laundry. This brook has watered and brought life. It has never failed. I expect to see a Sunday school fawn lying down with a lion, and an apple tree with fruit of waxen Sleeping Beauty rosiness.

I decide against exploring the island. There is no point, not when every corner is visible at a glance. Instead, I explore the sense of calm I am feeling. In a village like this nothing happens—but only if you measure time in minutes. In the course of an hour this little cradle of green, nestled inside a volcano, bustles with life. There is the warble of a bird and the singing of a mother as she fetches a bucket of water from a freshwater pool. A child spears a stick of firewood with the point of his bush knife. He flicks the wood up to his other hand. In Samoa there’s no Kiwi bull-ata-gate squaring off at a task. Instead, there is a graceful economy of movement.

The father and the boy are playing together in a tide pool. In the last light, more rain sweeps a sparkling grey across the sea and past the is land. There’s the smell of a cooking fire. A black cat springs through undergrowth. Children wrestle each other for possession of a bar of soap. There is laughter from across the cricket pitch.

I am called to dinner. The food is brought in: chicken, yam, taro•served on a banana leaf. A pot of home-roasted cocoa of smoky deliciousness is served. The pressure lamp is lit, and splutters and roars and smells in the twilight. The matai gives his evening reading and prayer in a soothing murmur. Thankfulness for the bounty of these islands. Prayer for the young men out at sea bringing home the catch. Gratitude for the health and happiness of the visitors. Fositau, our Visitors Bureau guide, and the matai sing together: a weave of flowing honeyed sound that is also giving thanks for the beauty of this life. I lean back on a post and feel its skin worn smooth by the years. I wonder at the reaction of early palagi seamen coming from the foul grime of Europe to this garden of plenty. I wonder at mine.

We leave the next morning. Days later, I learn that soon after our departure there are fisticuffs on the beach. I think of these quiet, picturesque men punching, grappling for a footing in the loose coral gravel, drawing bright red blood. A surge of adrenalin filling a quiet morning. Filling another chapter in whatever feud it was.

Why should I be surprised? Supposedly peaceful small communities—whether they be Aramoana, Paerata or Port Arthur—are precisely the places where grudges are most likely to stew.

To see Fa’a Samoa at its strongest, I want to spend time in the isolated villages of Savai’i, which is less populous than ‘Upolu and lacks the relief valve of a main centre like Apia.

My host is Fa’asilifiti Moelagi Jackson, who runs a lodge in the village of Safua. When I arrive, she has just returned from a whirlwind tour of family in the US, so I keep out of her way by exploring the island, which resembles a giant Rangitoto.

I visit the Pulemelei Mound, the largest stone monument in Polynesia. It is a 10-metre-high stone platform the size of a football field that pushes mysteriously out of the jungle like some Mayan ruin. Oral history makes no mention of it. Its purpose is unknown.

On the southern coast, the Taga blowholes are one of the Pacific’s most extraordinary natural wonders. Their concussive boom can be heard for miles. Well before I reach the holes I discover the raw rock beneath my feet is hissing and bubbling—this because the porous lava is pressurised by the force of water that comes with each wave surge. Close up, the blows explode with the sound and fury of a volcanic eruption. There are thumps and rumbles in the very foundations of the rock. I toss coconuts into the hole; they are thrown 60 metres into the air and ride the spout like cartoon characters.

Returning home, I stop to watch a demonstration of how siapo, tapa cloth, is made. First, the woman strips bark from a stick of mulberry, like skinning the legs of a rabbit. The outer bark is peeled back to reveal clean skin. There is a sweet sugary smell of sap. With an ironwood mallet she flattens the bark, working from the centre outwards, carefully gauging the strike to keep the thickness uniform. She pins the pelt on the floor with rocks so it dries under tension and doesn’t crinkle. There are holes in this fibre from incipient buds in the original trunk.

On a previously dried pelt—close to hand à la Graham Kerr—she repairs the holes with patches of fibre glued in place by arrowroot paste. On a carved board she rubs red/brown volcanic clay, and presses the fabric to make a print. To vary the colour she sometimes adds Reckitts blue. This is the woman who has been banished from her village.

I visit the market. This activity doesn’t involve a clogged assembly line of supermarket trolleys, but rather a placid stroll where you must use your senses, skill and discernment to establish the use-by date of the products. But there is no mistaking freshness when you see it. Tightly furled cabbage, glistening, gleaming fish with deeply transparent eyes, neon reef fish, home-made chilli sauce, burly pineapples, plum tomatoes, cocoa beans coddled in the pink mucus of the pod, fluffy pork pies, or pig cakes, as they are called, limes, chives, swamp taro the size of Jonah Lomu’s thighs, wild fungus, charcoal, virulent carcinogenically pink ice-cream and bottled sea slug innards sold by an old man in a T-shirt that advertises the Kodiak rain festival. His son lives in Alaska, he tells me.

Also available are frozen turkey tails and mutton flaps. Turkey tails are about 80 per cent gristle and 90 per cent fat—grey and intractable. Speaking of grey, there is nothing more profoundly dead than a cold boiled mutton flap. Just viewing these delicacies on a plate causes your arteries to coagulate. The aesthetics of such a meal are not helped by the seriously diseased cross-eyed teetering scabrous cats that always seem to be lurching around your legs as you eat, uttering thin but determined mews.

I catch a bus at the market. Samoan buses are something else, starting with the names: Ocean of Light, Jungle Boys, Expo-roo, Lady Havana. They’re painted in screaming blues and pinks, and are festooned with seagulls, sunsets, kangaroos, hibiscus and owls (owls being a symbol of war). In Samoa, you don’t take the number 10, you take the Ocean of Light or the Queen Poto (so named in honour of Mr Poto’s daughter, Queen.) Each bus is an institution. A work of art.

The interiors are awash with decoration. On my bus little playboy bunny-girl doodads on springs wave about on the dash. Pinned to the coachwork of the body, which is bolted to a truck chassis, is a poisonously-hued Taiwanese acrylic shag-pile tapestry of The Last Supper that does serious violence to Leonardo’s memory.

Our driver—masked by a pair of welder’s sunglasses—is a study of impassivity, as well he might be. Only with reluctance had he detached himself from the ‘ava bowl at the market. A cruisy, tranquillising, numbing kind of drug, `ava is the perfect accompaniment for the roadcraft of these drivers. The buses loaf along with a barging big-boned ease. There is no suggestion of incipient Filipino-style bus-plunge.

I am sitting at the front. The passenger next to the driver is smothered by four children. As they cuddle and laugh together I make a note of how nice it is to see a father being so attentive and loving. I give up my seat for a woman, but she refuses. Instead, she primly perches on my knee as if it were the most normal thing in the world. Then I realise that in this world it is. I twist around and discover mine was the last vacant knee. Everybody is sitting on each other’s knees.

At one stop the kids jump off down the steps, and I realise the man they’ve been clambering over is probably an uncle, or maybe no relation at all. I think of the bus to downtown Auckland. The comparison crystallises the difference between the two places.

There is no better place to be than aboard this little bus, this Ocean of Light, loafing along a sun-sparkling road, with the smell of perfumed oils and the feel of absolute trust and physical togetherness to sustain the journey. By comparison, palagi life seems unattached, lonely and somehow flimsy. Life in Samoa involves more intensity of human interaction than you’d find in Queen St in a thousand rush-hours.

Finally, Moelagi is ready to let us join her on her rounds. She takes us to visit a district president of the Catholic church who is very ill. A bus full of villagers files in and sits cross-legged around the fale. On his sleeping mat the president is propped by embroidered pillows. One of our number speaks. “We ask God to add still more days to your life. I’d like to say, without your presence there isn’t any smoothness in our meetings, and we will miss that if you leave us. It’s terrible to think of you dying, because we have been sheltered by your wings. When they fold we will be exposed.”

In Samoa there is no embarrassment about death. Palagis making such a visit would have been talking about the weather. Or biffing the president on the shoulder and telling him he would be up and mowing the lawns in no time. The shining kindness and ornate poetry of the words that trace this man’s good works brings a tender meditative calm to the room. It’s at times like these that your mind travels 2500 years back to absorb and feel strengthened by the support and love of fa’a Samoa at its very best. As a palagi, I can only imagine that feeling.

We repair to a nearby house to divide the cartons of mackerel given by the president in exchange for our presents. I am called into the fale. I am motioned to the head of the room, and one of the old men begins to address me. I hear the same soothing cadences, the same deliberation, but my guide, for some reason, has an attack of the nerves and can’t translate for me. Presently I learn that I have been made a matai, that my new name is Tupai from the district of Fa’asaselega. Never having made so much as pool monitor at school (an oversight that still rankles), I don’t quite know how to take it, especially since I am now descended from the original Tupai, a high priest of the supreme goddess Nafanua.

I ask Moelagi how come Arno, the photographer, wasn’t chosen. “We discuss this, but Arno is jumping up and down all the time taking photos. When someone is do ing this it means he is the server, not the master! Also, he was too skinny!” Moelagi makes this last observation with a liquid shift of the eyes to my belly

[Chapter Break]

In the days that follow I become acutely conscious of just what it takes to be a matai. I learn that I have 2500 years of chiefly lineage to become totally familiar with. I have to provide and mediate for a whole branch of family. I need to learn not just Samoan, but the chiefly forms. How to say a prayer, to sing, to orate, and whose post is whose in the meeting house. I begin to make inquiries about the chances of accepting the tide in an honorary capacity only.

Moelagi won’t hear of it. “You are now forever linked to your family here. As one of the heads of your family, you have a duty to them. But when your chips are down they will help you. That is why I am going to drag you around the island tomorrow! To introduce you!”

We first visit my new brother, Ulu, from the village of Tafua. Back in Apia, I’d heard from American ethnobotanist Paul Cox how Ulu thwarted the loggers that forever circle the remaining stands of rainforest on Savail. Cox—one of the breed that struggles through the jungles of the world, researching tribal medicine, searching for the eldorado of an AIDS cure—had made it his personal mission to help Ulu.

Cox’s interest was medical. On Savai`i he found that healers were using bark to treat hepatitis. “Hepatitis is viral, and I got interested because we don’t have anything to treat virals.” Cox discovered the active molecule appeared to have some promise for treating AIDS. Cox is not involved for the money. “I made sure the intellectual property rights and the patent belong to the Samoans.”

Samoans place great value on natural medicine. Earlier I had watched a natural healer treat a young boy for an upset stomach.

There was a power in her performance, a healing sense that lay in the ritual: the shaving and scraping of the root, the mortar and pestle percussion of boulder against hardwood as she pounded the fibre. This was no perfunctory prescription. The mixture released a faint ginger tang into the room. She scooped the crushed fibre into a square of linen, twisted it and wrung a milky fluid from the fibre into a cup. She called for the boy.

He left the TV game show he had been watching and presented his tongue for a spoonful of mixture, immediately wincing at the taste.

With a conjurer’s aplomb the healer whipped a ball of crushed root and leaf into his mouth, and plucked it out just as quickly. By now he’d had enough. With a firm hand she pinned him to the floor. There was something vaguely agricultural about the process. She let go and the child sprang off like a freshly drenched lamb.

The spiritual connection between man and nature is strong in Samoa, which explains why villagers have largely held out against loggers. But they are vulnerable: they must build their own schools, and with a per capita income of less than $200 (on which the churches have dibs) the only apparent means of funding has been to yield to the loggers.

Even so, Ulu refused: stood in front of the bulldozers. Cox got wind of his stand and offered to fund schools in return for the villagers signing a covenant to protect the forest for a 50-year period Traditional uses would still be allowed.

The concept achieves two objectives, Cox says: education and environmental protection. Similar covenants have now been signed with five villages.

But there was a problem, one that highlighted the prickly pride of Samoa. A Swedish aid organisation brought into the deal wanted the money almost a million dollars to be dispersed by an NGO in Apia, and not given direct to the villagers. This was totally unacceptable to Ulu. It was seen as a slur on his integrity.

It was decided that Ulu should meet the donors in Stockholm. Says Ulu, “You see, the one million is truly not important. If there is any greyness behind the gift I will not accept it, not even millions. I thanked them for bringing me to Sweden, but then I attack the report that says we shouldn’t handle the money. It was insulting me without my knowledge. I said, `You do that in Samoa and you will be tied and thrown into the fire!’ I was not afraid to speak directly. ‘God knows I am a poor man, and my village is poor,’ I told them, ‘but the masters of the village make the decisions, not some place in Apia that wants only to cuddle the money!”

For the sake of village pride, Ulu was willing to jeopardise the whole deal.

Ulu indicates it is time to eat. His daughters, heads bowed, offer pink plastic bowls for us to wash our hands. These are replaced with trays of corned beef and mutton flap. When we finish, the girls again present the finger bowls. One backs out of the fale with all the obsequiousness of a head waiter, turns and broadcasts the water across the gravel yard with a dismissive slop. Like a builder emptying tea dregs from his cup.

At another relative’s home, basketloads of food gifts for the family are loaded into the Landcruiser. “We believe that if we are hungry we can go to any house. They will provide. They know they will be in those shoes one of these days.” I think of the Samoan expression that means “pretending you are not at home when the relatives call.” This has now been modified to include refusing to answer the phone on paydays. But I keep it to myself.

Samoans romanticise fa’a Samoa in much the same way as New Zealanders describe Christmas as the season of good cheer. Indeed, with all the family commitments and constant celebrations, life in Samoa resembles nothing more than an exhausting and endless Christmas.

There’s nothing voluntary about Samoan generosity, not when your place in the scheme of things is established by how much you give. The family, the church, the village—they all expect contributions for countless reasons. One day it will be the women’s committee at the door demanding a can of corned beef (at half a day’s wages) for the feast they are holding to celebrate the new sign they have erected down at the bathing pool . . .”and don’t try giving us mackerel or you’ll get a hiding!” The next day it’s your father at the door.

Auntie Elsie needs $20 (three days’ wages) because she is going to Niu Sela for the first time. And you don’t ask who auntie Elise is, or why she is going to New Zealand. You give. Matai do not perform their elaborate speeches for nothing either. One expat explains: “Matai’ll turn up for the opening of an envelope and expect payment!

Anybody home from New Zealand or the States can expect a line-up of maybe 50 matai all eager to welcome you and expecting $20 each. Try to dodge coughing up and you get fined 10 cartons of mackerel!

“Some families are barely paying church dues, there are so many demands. The worst is that people borrow to meet obligations . . . we’re talking $40,000 for a funeral! It is so competitive. We had a radiothon, and people were writing down who gave what. Someone said to me they’d been surprised I hadn’t given anything!

“A wedding isn’t about ‘I got a toaster from this guy or a juice extractor from her.’ It’s about feeding everybody and making sure the guests go kept a real good book on it.”

Moelagi takes me to the top of Mt Matavanu, one of Savaii’s 470 volcanoes, to pick cuttings as gifts for our other stops. We pass through cleared cattle lands. There is something about the thatched cottages that reminds me of a settler’s whare. I feel that instinctive Kiwi satisfaction at a close-cropped paddock, but most of the land is still rough.

The trail leads into the heart of Savai`i, the cloud forest of the uplands. Everywhere there is a pestilence of vines, a smothering blanket that makes the New Zealand weed “old man’s beard” seem clean shaven. At the summit there is a chill breeze and always in short supply in Samoa space and silence. Returning to the humid clutter of the coast is like sinking into a warm bath. The trail is crowded by glossy leaves as big as elephant ears.

On the north coast we stop dead for forgiveness. People crawled into water tanks and septic tanks and stayed there for four days. They had to shelter from 200 kilometrean-hour winds or they’d have been flayed alive by the gravel.”

We reach one village that was painstakingly rebuilt after the first cyclone only to be destroyed by the second. Brokenhearted villagers have since retreated to the interior. “You see the Catholic school? The waves were crashing through the ground floor, so they went to the top floor, but the roof flew off. They had to run into the jungle.”

The double punch of these cyclones caused great loss of heart in Samoa. When you place the damage from Val alone in a New Zealand context, it is not hard to see why. The $NZ535 million bill sounds big enough, but when you consider that New Zealand’s per capita income is at least seven times greater, and that we have 20 times the population, you arrive at a NewZealand equivalent impact of $74 billion dollars. And this after `Ofa.

On top of that was the arrival of taro blight that destroyed 90 per cent of this staple crop. Samoans are a resilient people, but only now is their spirit returning.

Economically, the country is recovering, too. The latest figures show exports up by 32 per cent in 1996 to $11 million. And villagers can now earn a reasonable living cutting copra. One company has pioneered the export of cocoa and also `ava powder, which is used for cosmetics and tranquillizers, but it is the giant Japanese Yasaki wire factory, employing 1400, which accounts for about 80 per cent of exports.

Given that Yasaki pays only $1.25 an hour, I wonder why New Zealand firms aren’t taking advantage of the same willing workforce that powered New Zealand factories in the 1970s. Some 55,000 want jobs when there are only 20,000 available, keeping workers’ conditions decidedly Third World.

A key ingredient of the recovery has been the reorganilanding gear of the airline’s only plane. Only brilliant flying by the pilot prevented a major tragedy and total financial ruin.

Although tourism now brings in $100 million per year, some 40 per cent of Samoa’s income is from remittances and aid, to which New Zealand contributes $7.5 million, most of it spent on education and training. With half the population under the age of 15, continued migration, which reduces a natural growth rate of 3 per cent to 0.6, is essential for economic survival.

We return to Moelagi’s home village of Safua. She suggests I attend a meeting of the Lalomalava village council. At the fono, possibly an hour is devoted to speeches before business. Eventually, a matai sums up: “We all loved to hear your nice speeches, you were like birds singing in a tree. I think this is enough speech for us all.”

At this, a young man makes a high-pitched call, lifts a coconut shell of `ava above his head and trots stiff-legged to serve the first matai. With an exaggerated flourish, he lowers the shell. He repeats this until all are served. I make a speech thanking them for the invitation and for sharing such fine `ava with me—which, incidentally, is served in a jealously observed and hard-won order of seniority. A mouthful of `ava drunk by the wrong person at the wrong time is an open invitation to a full-on brawl. This also applies to anyone leaning against the wrong post, an offence which can lead to court action.

But even the sacred rituals of the fono are privately subject to the usual scoffing Samoan humour. One matai tells me: “Why you want to go to a fono? A whole lot of chief bloody Sitting Bulls beating around the bush. Nothing ever gets done.”

At Lalomalava the first hour of business is spent dealing with a miscreant pig that is being kept in the village against the rules. One matai says it has been removed. Another reports that he saw the pig that very morning. Some are in favour of offering the pig one more chance, but the fono fixes a fine of $100 at least two weeks’ pay. The head chief now says his piece. He thinks the decision to punish is the right one, but maybe it would be right to drop the fine down to $20.

As he speaks, sunlight strikes his bald head that seems to merge with the polished hardwood of his post. The fono’s fale itself exudes a sense of power. They are assertive, beetle-backed structures, which, when sheathed in corrugated steel, look like a centurion’s helmet.

There are some hours to go, but I am having a private battle with spine-shattering waves of pain, the result of sitting so long with my legs crossed. It is rude to outstretch a leg. All around me these men, some in their seventies, sit with the ease of yoga masters, rapping the ground in front of them as palagis do a table to make a point. I have to take my leave.

Later I accompany a subcommittee of the women’s committee proper, which each week inspects the houses, prowling for untidiness. For hours they poked and pried, noting infractions down on a clipboard. Every house passed muster on this inspection, but the women also collected fines imposed from the last tour.

Rules. At one level they are about suppressing conflict. At another, when there’s precious little else to do, the politics of applying them provides welcome diversion.

In palagi terms, life in the village is like having your entire family—in-laws and all, along with half the street—coming to stay permanently, each armed with a 2500-year history of righteous interference in the smallest detail of your lives. And demanding to be fed.

There is more to the process of control than just rules and fines. Avalogo Eddie Ripley, a senior official at the Visitors’ Bureau, explains: “Here if the son does the stealing, the father gets the punishment too . . . all the chiefs will curse the father, telling him he never knocked sense into his child. For any mistake there is a formal process of mocking. They will call you a dog. Then any problem in your family from the past will be dragged up. The village soon learns of this after such a scolding you feel like putting a bullet between your eyes.

“Nobody forgets. Say I am having an argument with you and I am losing, and you were mocked once before I will say, ‘You are a mocked one. Who should listen to you?’ I might even say, ‘Mark, how can you talk when everybody knows your grandfather was roped like a pig?'”

I am reminded of a Japanese proverb that says the exposed head of a nail must be driven flush. In Samoa the concept of being a perfect cog in a perfect machine has a Japanese flavour to it. There is that Asian submission of self to a corporate structure, where all energy and rivalry is rigidly channelled and confined within a maze of ritual.

I start to regard Western civilisation, with its tradition of free thought, in a different light. Somehow, big city New Zealand with its rat-race of traffic jams, mortgages, the rule of the almighty uncaring dollar and the 9 to 5 tyranny of the time-clock seems far less fraught with complication: a veritable paradise! The emancipation of anonymity!

That night there is an impromptu dance. To the strains of “Do the Bossa Nova” an enormous matai, all wobbling extremities, does a bizarre medley of dances from Elvis impersonation through to a lewd twist. There is more grace and timing in his little finger than most welded-spine palagi could muster in a lifetime. My jaw aches from laughter while my back is still on fire from the hours spent discussing the truant pig.

Over a Vailima beer in this room full of laughter, I consider a contradiction that has been troubling me. Imagine a society which rests on the fear of God, on brutal discipline of children and on oppressive social control and you come up with some kind of pinched Romania crossed with Scotland. You certainly don’t come up with a vision of merriment.

But Samoans laugh like nobody else. Great gales, gusts and squalls of laughter that set the entire body shaking. There’s even a formal jester’s role, most often fulfilled by old men and women. At any gathering they’ll perform outrageously ridiculous mocking dances that see even the pompous and the pontificating dissolve into uncontrollable hysterics.

I decide there is really no contradiction: the Samoan sense of humour is heightened precisely because of the rigidity of the system. It is pressure relief valve humour that offers a moment of freedom, of escape from the tensions, and it’s a constantly bubbling undercurrent.

Humour is one response to pressure. But so is violence and anger. A New Zealand-sponsored study shows that sexual and physical violence is rampant in Samoan culture. If recognising the problem in New Zealand has been a struggle, in Samoa it is going to be many times harder. A woman facing domestic abuse must cope with terrifying isolation. Most women live in their husband’s village, away from their own family. A woman complaining in the village will be exposed to a great deal of anger from the accused’s family for impugning its honour. If she goes to the police she risks punishment from the fono for sidestepping its authority.

This is all quite apart from the question of what in Samoa constitutes acceptable physical punishment. If this was New Zealand, social welfare would have to start with the schools. Two ex-pat teachers told me horrifying tales. “One girl was called up at assembly for wearing a short-sleeved top. When she got to the front she was slapped and pushed to the ground by a male teacher, who shouted at her, ‘Why didn’t you come straight to me?’ The girl had walked around other students. She was forced to return to her seat and then come back directly. She was slapped around the head again. She took several days off school. This was normal.”