On the metal – the tin miners of Port Pegasus

A tramper’s headlamp arcs a trail through the subterranean recesses of New Zealand’s southern‑most mine. The 85-metre tunnel, driven into solid granite, survives as one of a handful of relics from New Zealand’s only tin rush—a stampede of ill-prepared men into the miserable weather and impenetrable scrub of southern Stewart Island.Despite high hopes and extravagant claims little metal was ever recovered.

I wade gingerly into the flooded tunnel, my tramping boots stirring up a cloud of silt and rotting leaves. Frigid, thigh-deep water sets my skin tingling beneath two layers of polypropylene leggings, which offer little comfort. I test each step before transferring any weight, wary of repeating the misfortune experienced by a geologist flatmate: while exploring a tunnel in Central Otago he stepped into a submerged shaft and went in over his head, shorting out his lamp. His soaking, pitch-black crawl back to the entrance didn’t bear thinking about.

In the beam of my head-torch, crystals of mica and quartz glitter in the rock walls, betokening a promise of mineral wealth—a promise that lured the builders of this tunnel to wield hammer and chisel against the solid granite. The marks of their tools are preserved in the rock, and here and there a spike hammered into the wall or a cubby hole hewn out of it hints of some long-forgotten purpose.

By my reckoning, I and my companion are the southernmost people in New Zealand, deep within the granitic heart of the Tin Range, in southern Stewart Island. We are here for tin, a metal that is often associated with cheapness and inferiority‑”tinpot,” “tin god,” “tinhorn”—yet without which we would have no pins, paper clips, staples, solder or any of the hundreds of foodstuffs that come sealed in tin cans.

Tin has an esteemed place in human history. For thousands of years, copper was the sole working metal of humankind. Then, around 3500 B.C., somewhere in the Middle East, an unknown metalsmith discovered that a little tin added to copper in the smelting process resulted in a much harder metal alloy: bronze. An age was born—one which would last two millennia until the advent of iron.

The element tin (symbol Sn, after the Latin stannum) is relatively rare in the Earth’s crust, occurring at just 3 ppm (parts per million), compared with 15 ppm for lead, 70 for copper and a massive 50,000 for iron. Among the metals rarer than tin are tungsten (1.5 ppm), silver (0.1) and gold (0.005).

Tin deposits being scarce, trade in the metal and its ore played a key role in political and economic development. Indeed, it was the discovery of tin in Cornwall that precipitated the Roman invasion of Britain in 55 B.c. Although plastic and aluminium have taken over some of its functions, tin continues to find a surprising number of applications, many of which make use of its low melting point, malleability and prodigious capacity to form alloys with other metals. From white-metal bearings in motor vehicles to high-tech superconductors, pewter jugs to organ pipes, tin makes its presence felt in both industry and art. Float glass gains its perfectly flat surface by being poured onto a bath of molten tin. Most of us carry a fair amount of tin around in our mouths in the form of silver amalgam fillings, which are around 25 per cent tin.

Most of the world’s tin is mined from alluvial deposits in Southeast Asia, and although the price of tin has never really recovered from a crash in the mid-1980s, it remains four times the price of copper and five times the price of zinc and aluminium—around $10,000 a tonne.

In New Zealand, the Tin Range is the only locality where tin is found in any quantity. The range itself is the southern portion of an undulating ridge system of some 15 kilometres which stretches southward from Paterson Inlet to Port Pegasus. It was originally called The Remarkables, but the name was changed to avoid confusion with the more famous range overlooking Queenstown. Such is the striking nature of the terrain here that it is a moot point as to which range is more deserving of the name.

The Tin Range is not high. Points vary in altitude from just over 500 metres at the southern extremity up to Mt Allen in the north at 750 metres. From the summit of Mt Allen a grand vista unfolds. South lie the drowned river valleys of Port Pegasus, a natural harbour so large that Thomas Shepherd, surveyor of the first New Zealand Company’s expedition in 1826, wrote: “In it may be found good anchorage and room for all the ships in the British dominions.” And that was no exaggeration.

To the south-west the Fraser Peaks rear up their granity heads, most markedly in Gog and Magog. Whoever bestowed on the cones their Old Testament names apparently failed to realise they already had Maori names. Gog was called Kaka-kura (red parrot), as a reddish streak near the top reminded Maori of the face and neck feathers of the kaka, which once abounded on the island. Magog, being squarer than its mate, was thought to be “angrier” than Gog, hence the name Tu-pouri (standing dark and gloomy).

In his inaugural botanical survey of the island in 1907, Leonard Cockayne was considerably moved by this landscape: “This is the veritable land’s end,’ where naked granite cones pierce the heavens for 1,000 ft., rising from a bleak and barren moorland framed by the evergreen New Zealand forest, here at its most southern outpost, unless we include its grotesque subantarctic continuation on the inhospitable Aucklands.”

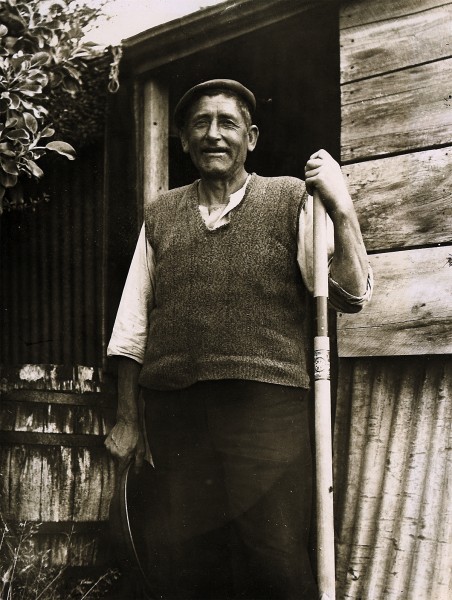

strikes a pose with the trusty tomahawk he used to hack his way through dense Stewart Island bush following the discovery of stream tin at Port Pegasus. The son of a Scottish crofter, Black had a close affinity with the island, and is buried with his wife in Halfmoon Bay cemetery.

Due west of Mt Allen are the Deceit Peaks and the pepper-white arc of sand that is Doughboy Bay. Far off in the distant north are Codfish Island, a kakapo refuge, the Ruggedy Mountains and the Mt Anglem massif, Stewart Island’s highest point. Jumbled, broken country lies to the east, with Port Adventure beyond. All excepting the open tops is forested, the green mantle swathing the entire countryside down to the waterline, as it once did the mainland.

The landscape has an almost surreal aspect. It is Tolkien country, a place where you might expect to find a hobbit snoozing under a leatherwood tree. Or sheltering there from a gale. Stewart Island lies between the latitudes 46 and 48 degrees south—smack bang in the middle of the westward wind drift. There being no other landmass at this latitude save the tip of South America, westerly winds travel unhindered for thousands of kilometres over the Southern Ocean, gathering both velocity and moisture before slamming into the exposed tops of Stewart Island’s uplands.

Round-the-world yachts and wandering albatrosses seek out such winds for their peregrinations, but to those who venture onto the slopes of the Tin Range they bring a climate that is at best unpredictable and at worst utterly atrocious.

Once, camped near a tarn on Mt Allen’s eastern side, I was caught out by a screaming nor’wester. In the relative shelter of the mountain, I listened in awe to wind gusts that roared around the hillside before slamming into the sides of my tent. On the ridge line it would have been impossible to stand, let alone walk.

Waterfalls cascaded into the tarn, forcing its level to rise nearly up to the floor of the tent. After a day and a half the tempest eased and I was able to continue my trek.

It was into this desolate and unforgiving place that miners last century flocked to make their fortune.

[chapter break]

When the cry of “Land ahoy!” went up off southern Stewart Island in March 1770 from the crow’s nest of the Endeavour, it wasn’t long before the connection between the unusual landform and its mineral potential was made. VVhile most of the keepers of logbooks, from Cook through to the draughtsman Sydney Parkinson, simply made note of the granite monoliths that greeted them, alluding to their “sugar loaf” appearance, Joseph Banks, the botanist, speculated on what might lie hidden within the rocks.

Stewart Island’s outcrops were, he wrote, “amazingly full of Large Veins and patches of some mineral that shone as if it had been polishd or rather lookd as if they were realy pavd with glass; what it was I could not at all guess but it certainly was some mineral and seemd to argue by its immense abundance a countrey abounding in minerals, where if one may judge from the corresponding latitudes of South America in all human probability something very valuable might be found.”

Banks’ words proved prophetic when, in 1882, gold was discovered in Pegasus Creek, which flows into the North Arm of Port Pegasus. Two of the original prospectors, Louis Longuet and Harry Allen (after whom Mt Allen takes its name), also worked further inland, into the wild heart of the Tin Range, and were the first known party to complete the rugged overland trip to Paterson Inlet.

The early gold prospectors were hampered by low yields and the troubling prevalence of a mysterious black sand in their wash—dubbed the “black plague.” In December 1888, prospectors George Swain and James Thomson of Halfmoon Bay found an unidentified mineral in Pegasus Creek amongst the “beastly” black sand. A sample brought by islander Charles Robertson to the provincial government analyst, James Gow Black, professor of chemistry at the University of Otago, was assayed and found to be stream tin.

Black and Robertson lost no time in heading back to Pegasus. At Bluff they chartered Captain Robert Scollay’s cutter Enterprise, loading supplies and mining equipment. In those goldrush-fevered times, their preparations didn’t go unnoticed, and as they butted into the Foveaux Strait chop, over their shoulders they spotted a pursuing cutter.

The professor persuaded Scollay to push on south to Pegasus, despite the rough conditions, and the party arrived at Pegasus Creek ahead of their pursuers. There they found George Swain and half a dozen others digging alluvial claims for gold. Black related the news of his discovery, and, judging by the large quantities of garnets and stream tin found in the wash, announced that prospects for tin mining were promising.

He returned to Halfmoon Bay with a sackful of samples, which were crudely smelted into tin at Scollay’s smithy. On his advice, Swain and party pegged out 120 acres of the best ground before sailing for Invercargill to secure the right to work it.

With nervous excitement, they lodged their claim, then anxiously sought to return to Pegasus, as news of the discovery had got abroad. They were agitated by reports of a prospecting party from Melbourne lying weather-bound at Port Adventure.

After boisterous south-easterlies around Port Adventure forced back the 100-tonne paddle steamer Avarua, Professor Black and party were forced to consider the only alternative: an overland trek from Halfmoon Bay. So began an epic bush-bash through the untracked and largely unknown mountains of the interior, into the domain of the dreaded leatherwood.

[chapter break]

Around the 300-metre contour, the forest thins out to a subalpine scrub dominated by manuka, inaka and mountain leatherwood. Above this, montane shrublands take over. Here the prevailing “Brave West Winds” howl over the open, exposed tops, forcing vegetation to present a low profile to the elements.

It is a surprise, then, to see the forest giant rata growing in such an inhospitable environment. Here, however, it is not the tree of massive boles and branches characteristic of rata in the lowland. It is reduced to gnarled shrubs which cower behind any shelter available. Manuka, too, is forced to adopt a prostrate carpet form, in the most exposed locations creeping just a few centimetres above the ground.

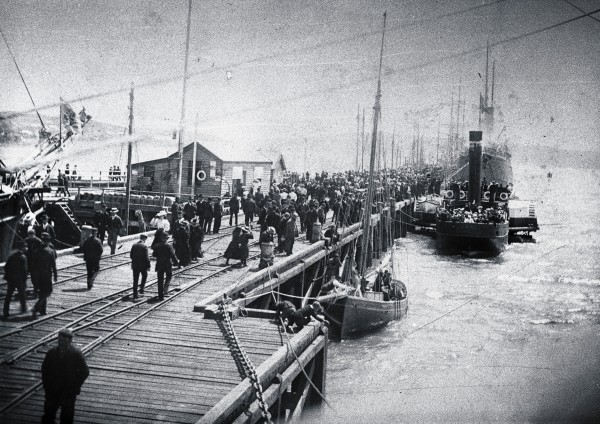

voyage across Foveaux Strait in under three hours. Awarua and the s.s. Dispatch, a small screws teamer (above), were the main supply vessels for tin miners. At the height of the rush, both craft, along with coastal cutters commandeered by eager mining parties, crisscrossed the strait, carrying the hopeful in one direction and the

Adaptation is the key to survival in this forbidding climate. Plants line up in lanes behind schist tors that protrude skywards, themselves showing the effects of eons of exposure to the winds of the Roaring Forties. It is not only rocks which provide shelter; anything that obstructs the wind will do. On the southern Tin Range, red tussocks act as windbreaks for dwarf manuka and gnarled mountain I eatherwood. It is a strange sight to see the vegetation all lined up, as if it had been cultivated into neat rows by some indefatigable gardener.

The interplay between climate, vegetation and elevation is nowhere better illustrated than in the dramatic lowering of bushline as one proceeds south through Stewart Island. It decreases from 700 m on Mt Anglem, 560 m on Mt Rakeahua, 520 m on Table Hill, down to a low of 440 m on the southern Tin Range. Wind, here, is that indefatigable gardener.

Mountain leatherwood, a type of tree daisy originally documented by the Rev. William Colenso from Mt Hikurangi, on the East Coast, is the ubiquitous plant on Rakiura’s highlands. Known to locals as tupare, these stiffly branching shrubs, with their rounded leathery leaves, green on top, white underneath, are the bane of anyone masochistic enough to venture onto the highlands. Colonial botanist Thomas Kirk described the leatherwood he encountered on Mt Anglem in the 1880s as being so dense that “a retriever dog was unable to proceed.”

Varying in height from four metres in sheltered sites to below half a metre in exposed locations, leatherwood is too short to crawl beneath and too tall to step over. The only way is “through,” an approach which gives the stiff branches abundant opportunity to rip clothing and draw blood from the flesh thus exposed. Into this botanical tangle Swain, Black and party plunged, progressing at an excruciatingly slow pace.

Bruised and exhausted, they arrived at Pegasus on the morning of the fifth day. Immensely relieved to see the field unoccupied, they set about pegging out fresh ground. That evening, enjoying their first decent slumber in days, they were startled awake by the whistle of a steamer. Thinking this signalled the landing of rival prospectors, four men were immediately dispatched to the alluvial deposits, ready to “peg out” at the break of day. It proved a false alarm in the form of the Awarua on a friendly visit. Two hours later, however, Scollay’s cutter arrived, and hot on its heels a flotilla of boats manned by rival prospectors. The following days saw a frenzy of pegging activity, and two days later a party of Tasmanians arrived.

The tin rush was on!

White calico tents sprang up in the valleys surrounding the Tin Range, but cutting tracks though the scrub proved agonisingly slow. The solution was a scorched earth policy: burn off the vegetation to expose the ground for prospecting. Sluicing was also used to strip the clinging peat mantle and reveal the tin-bearing alluvium and granite bedrock.

Unlike gold, tin rarely occurs “native” as metal. It is most often found as the oxide cassiterite (Sn02), a dull brown mineral which occurs in irregular veins or lodes, or in debris which has built up from the gradual weathering of tin-bearing rocks to form alluvial deposits in riverbeds and valleys or on the ocean floor close to land.

Cassiterite (also called tinstone) has a high specific gravity, enabling it to be concentrated by washing, which is why the early Pegasus gold miners kept finding “black plague” in their wash. It is smelted into tin by heating under suitable reducing conditions, using charcoal as both the fuel and the reducing agent. Once smelted, a tin sample can be tested for purity by bending it—tin emits a strange creaking noise, the so-called “cry of tin.”

Cassiterite is usually found as small crystalline fragments trapped in gangue (waste) rock. Occasionally a lump is found, but this is very rare. Rich ore contains about 5 per cent tin, good ore about 2 per cent. Skilful Cornish miners worked down to about 0.2 per cent from stream detrital deposits.

To be worked, the cassiterite-bearing ore must first be extracted from the native rock that surrounds it, crushed to release the valuable material and then washed. Crushed ore or alluvial gravels can be panned or thrown into running water flowing into a sluice box, so that the heavy ore particles settle out from the water and waste. Water is the lifeblood of a mining operation. As a consequence, most of the early claims centred on the streams draining the Tin Range.

On hearing of the discovery, Invercargill entrepreneur William Todd chartered the steamer Invercargill for anyone keen to see the new tin field at first hand. The excursion attracted considerable interest, with more than 40 southern gentlemen paying 40 shillings for the three-day trip.

Decked out in his finest threads, including a bell-topper hat, Todd was ill-suited to tackle the wild shores of Pegasus. He had barely taken a few steps up Pegasus Creek before his silk hat became entangled in the branches of an overhanging tree, toppling into a fine waterfall which was immediately dubbed Belltopper Falls.

Reporting on the trip was “Our Correspondent” from the Southland Times, who wrote up a humorous account of the journey, expressing the hope that it would not be long before “Stewart Island oysters in Stewart Island tins may be as familiar to the world as Bass beer.”

After touring the alluvial workings in Pegasus Creek, the sightseers headed for the lode claims at the southern end of the Tin Range. Evidently this journey took a lot out of them: “By the map the lode is distant from the anchorage three miles; measured by the way we travelled though the alluvial claims, six miles; measured by the exertion required well fifty miles is moderate. It would take you longer to go fifty miles but you would not be so tired.”

It took them five hours to reach Professor Black’s encampment, where, over mugs of hot billy tea, the good professor related to his visitors how he came to be encamped at such an exposed and inhospitable location. During the initial flurry of pegging alluvial deposits on either side of the range, he had decided to take a day off for some “scientific rumination.” He thought of the world and its Creation, and “thought his way down” to the ice period, when immense glaciers ground the sides of The Remarkables, scrunched the noses of Gog and Magog and scooped out the port of Pegasus. He concluded: “The boulders I know, the gravel I can understand, but whence the tin?” and then, with a flash of revelation: “By the living jingo, the ice has ground the tin out of the mountain and the rest of it is there yet! I’ll peg it off!”

By dawn’s early light he tomahawked his way though the bush to the summit, where he started vigorously attacking the outcrop with hammer and pick. Black’s party had only two days’ grace at “the lodes” before, on the morning of the third day, a rival party was spotted as they emerged from the bushline. “It was with considerable difficulty they were beguiled into proceeding towards a likely looking flat about four miles to Eastward,” recounted the professor.

Robert Fraser stayed on at PortPegasus until 1914, fishing and prospecting.

So it was not without some deception and trickery that Black, Swain and party took possession of the only claims where tin was visible in veins in the granite. The bush telegraph was soon singing the news that the professor’s party were “on the metal,” resulting in a mad nocturnal scramble to the high ground, so as to be ready to peg out likely ground at daybreak.

While touring the area, “Our Correspondent” and his brother were offered a share in one of the claims, as a shareholder wanted to sell “a portion of an immense fortune, only because he had no ready money.” The shareholder used Professor Black’s name freely as an authority for his statements, and took them around, showing them “great outcrops of lode, black with tin ore.” For 200 pounds a 48 per cent interest could have been acquired, securing a “fortune of thousands a year for unborn generations.” Our correspondent and his brother had thoughts of their uncle perhaps forwarding them the money. Picking up scattered samples, they inquired from the would-be vendor:

“Any tin in this?”

“That’s more than half tin.”

“What about this?”

“That’s at least 75 per cent tin.”

“And this?”

“That’s nearly pure tin.”

On showing some specimens to a Tasmanian, a tin miner all his life, they received a more sobering assessment:

“How much tin is in these?”

He looked the samples over.” one.”

“What? None at all?”

“I don’t think there is any.”

“What is that black stuff?”

“That’s wolfram.”*

“But is there really no tin?”

“Well,” he said, “if all the tin in them was gold and you had a mountain of it, it would not pay to work it.”

[chapter break]

Reports on the field varied from fair to good. Government geologist Alexander McKay indicated there was plenty of stream tin, but not in sufficient quantity to make extraction profitable. James Hector of the Geological Survey and experienced Cornishman R. G. Peters endorsed these views and advocated caution.

But dreams of wealth are not easily diverted. Newspapers continued to publish glowing reports, and company prospectuses quoted assays of up to 70 per cent pure tin from samples, fuelling the fire and luring prospectors to the field.

The prospectus of the romantically named “Winged Horse Great Amalgamated Tin Mining Co. Ltd” referred to a “solid mountain of tin” which, for the expenditure of just a few pounds, promised to give an income “beyond the dreams of avarice, for unborn generations.”

Public interest in the rush rose to fever pitch when Professor Black returned from Port Pegasus to Invercargill on January 23, 1889, and reported the discovery of “two rich lodes of tin-bearing granite in the Remarkable Mts.” The Land Office was immediately besieged by applications, and 11 areas of 60 acres each, plus 10 licences, were granted on that day alone.

A month later, a public meeting called in Invercargill to hear a Mr James Ashcroft’s tale of his tour of the field had to be moved to William Todd’s salesrooms due to the large turnout. Ashcroft called for the amalgamation of the claims and the formation of a company with capital of £100,000 to properly develop the diggings. Although admitting to be no expert, Ashcroft gave his conviction that the tin lode was “a gigantic thing to be measured by hundreds of thousands of pounds—a second Mt Bischoff [a famed tin-mining area in Tasmania].”

Observing the frenzy of mining activity, Louis Rodgers, a merchant with Dutch aristocratic blood, ten tons of general stores and an eye for business, saw a more certain road to profit than chipping at granite. Before long, he had established at Port Pegasus a general store, a post office (where he presided as postmaster and was paid a government subsidy for carrying the mail via the screw steamer Dispatch) and a hotel.

Rodgers proved to be one of the more colourful figures of the rush, providing miners with their liquid needs at his Pioneer Hotel, the southernmost pub in New Zealand. It wasn’t long before he was advertising the field as the “future Broken Hills of New Zealand.”

As news of the rush spread, most men on the island headed south to try their luck, or just to have a look. Inquiries by new chums as to where to find tin were probably met with the Otago diggers’ truism, “Gold is where you find it” or the Cornwall tinners’ circumlocution, “Where it is, there it is.”

John “Old Dad” Nelson, an ardent Salvationist, was among the hopeful. Olga Sansom writes of him in her book The Stewart Islanders: “He always wore something red; a jersey; scarf; red knitted cap; or a bit of red ribbon on his lapel. ‘It’s a fire, it’s a fire!’ he used to say.”

Old Dad accompanied one of the prospecting parties to Pegasus. The party made the arduous climb up Lees Knob, and with the spirit of discovery in the air coupled with the necessary “braces” on the way up, Old Dad, for the first and only time in his life, got drunk. On the descent, he let himself go, singing all the Glory songs with great zeal and emotion. Being winter, and typical Tin Range weather, his canvas trousers, stiff at any time, had frozen to him, and he kept falling over. “But he also kept everybody’s spirits up by singing ‘Hold the fort, I am coming!’ every time he rose again.”

Old Dad returned to work the lode claims with his son. Despite being the oldest miner there—he was close to 70—he often packed 60 or 70 pounds of stone down from the hills of an evening.

While most prospectors came and quickly went, finding the pickings too slim to compensate for poor tents, draughty huts and bad weather, some were in for the long haul. The men at Tucker’s claim laid the foundation stones of the first log huts of a township to be named Conliffeville.”

Conliffe, an experienced Tasmanian miner, was testing various Port Pegasus claims for Invercargill leaseholders.His

2 doubts of the field’s worth were aired in SS June 1889 when he wrote: “Very few claims have yet been touched with the pick and shovel, and most of them are not worth spending money on.”

In fact, many claims had been made haphazardly on maps in Invercargill, the claimants never having laid eyes on the country. It fell to members of the survey party led by T S. Miller and his assistants Harry Dundas and John Hay to undertake the arduous task of cutting traverse lines and subdividing blocks through the highly dissected terrain—a nonstop battle with the unyielding leatherwood. An able trio, it took them nine months and no doubt several sets of clothes to complete the survey of 111 claims.

The surveyors’ job would not have been made any easier by the volume of foot traffic crisscrossing the field and turning the peaty ground into a quagmire. By mid-1889 the track from Port Pegasus to the Tin Range was described by G. C. Baker, one of the claimholders, as “exceedingly bad,” given that the distance from the port to the lodes was two miles as the crow flies, and yet it took a strong man with a 50 lb bag of flour on his back two hours, and sloggers four hours. In walking the track “a man could not possibly avoid being covered up to the waist in mud,” wrote Baker, adding that it had been calculated that over that distance “a man raised one ton of mud to a height of one foot.”

It was a tough life, without a doubt, but it takes a lot to dampen a digger’s enthusiasm, as these lines from a ballad by George Swain, one of the original discoverers of the mysterious mineral in Pegasus Creek, demonstrate:

My clothes they are torn, my boots they are gone,

No gold shall we get anymore,

When I sit down and think what I’ve spent upon drink,

Then I feel I deserve to be poor.

Let us throwaway grief, we have faith in the reef,

And thoughts of it make us smile,

For no one can tell, in a short time from this,

We’ll be knocking about with a pile.

Alas, the only piles were piles of tailings.

The reef remained frustratingly elusive.

Professor Black, convinced of the existence of a mother-lode, decided to tunnel his way into the mountains to find it. His optimistically named Cornwall Tin Mining Co. soon reported it was 35 metres into the backbone of the range, and going through “very likely looking stone.” Another syndicate, the Pegasus Co., was in almost as far, through “hard strata, being micaceous granite and quartz intertwined.”

Reports in the Southland Times in October and November 1889 claimed that “the lode” had been struck, but nothing further was heard.

Elsewhere on the field, enthusiasm was waning. The Pioneer Hotel couldn’t have been selling much beer, for in May 1890 the patents office received an application from Louis Rodgers for “The Pegasus Tin-opener, for more rapidly opening all kinds of tinned meats, condiments, spices, or other things used when tinned.”

A few months later, Rodgers was bankrupt and finding it difficult to dispose of the buildings he’d erected at a cost of 8400.

When H. A. Gordon, the Inspector of Mines, visited the field he felt moved to comment on “the stern reality that all is not gold which glitters.” Guided around the area by Mr Rusha of the Pegasus Co., he found a largely abandoned field, with only 20 men left, compared to 240 at the height of the rush.

[sidebar-1]

He criticised Professor Black’s tunnel, now at 85 metres, for running parallel to the lode. And considering that the lode was not payable to work at the surface, he declared in his report: “Whatever money has been expended may be considered thrown away.”

Summarising the prospects of the field, Gordon wrote: “As far as large deposits of tin being found in the alluvial drifts is concerned, the general character of the country does not hold out great inducement for these being discovered. . . . It would never give employment to a large population.”

Riches beyond the dreams of avarice from a mountain of solid tin were put to rest. For a time, at least.

The field was all but deserted by January 1891, with only two men remaining and most of the claims being left to look after themselves.

However, two years later a second minor rush was sparked by an unconfirmed discovery of three tons of stream tin and 80 ounces of gold from an area on the eastern side of the Tin Range. Once again the population increased, and the post office reopened, only to close some eight months later due to a lack of mail.

Sir Joseph Hooker, director of Kew Gardens and an expert on New Zealand flora, was appointed by a group of London financiers to assess the field in February 1893, soon after the new discovery was announced. The Southland Times pounced on the story, posing the million-pound question: “Is our Pegasus a sorry jade and a fraud, or a nag of sound mettle?” For his part, Professor Black remained optimistic, claiming that, like its namesake in Greek mythology, Pegasus would shortly “mount exultant on triumphant wing.” But it was not to be, the newspaper in March reporting Sir Joseph as being “reticent.”

Like the miners, the newspaper reports petered out, the only exception being a 1896 snippet about a party of miners rumoured to have 5.5 tons of stream tin ready for shipment, but there is no record of the shipment ever being made. Many Southlanders were still of the opinion that the major reason for the field’s failure was the lack of capital development. Old Dad Nelson and Louis Rodgers were among them: “It only wants to be developed to prove this, they declare, but alas! The coined ‘tin’ is not plentiful either in or about Stewart Island.”

The government was petitioned for assistance, but was unwilling to invest until the field’s worth was proved—a classic Catch-22 situation.

Arthur Ford, an Irishman, eventually bought Rodgers’ hotel, store and post office as a house, and he and Robert Fraser, a Shetlander, remained in permanent residence at Port Pegasus until 1914. They prospected when conditions allowed and fished when they didn’t.

Needless to say, there would have been plenty of time for fishing.

[chapter break]

The story of New Zealand’s only tin field does not end here. During the first decade of the new century the Cornwall deposits, which had provided most of the world’s tin for 2000 years, were gradually giving out, leading to a worldwide appreciation of tin prices.

Tungsten was also in demand. Considered valueless in the original rush, wolframite was now quoted at over £100 per ton, due to the use of tungsten as a steel toughener. In 1912, these developments led a Dunedin group to float a company. Their prospectus waxed lyrical, with returns projected per acre grossly overstated: 100 oz of gold, 2 tons of tin and 4 cwt of wolfram, giving the fabulous total of £1200 per acre—some very creative accounting.

The company managed to procure the necessary “coined tin,” and £7000 was spent on installing modern machinery and erecting a jetty and buildings at Diprose Bay (named after one of the Tasmanian tin miners) in North Arm. A sawmill was soon milling timber for a tramline “4 miles and 49 chains in length” which was cut up the western side of the Tin Range into the headwaters of McArthurs Creek to a small dam (a remnant of the original rush), where water pipes and hydraulic mining equipment were laid out. The plan was to provide water for sluicing the alluvial deposits, the profits from which would finance the development of the main ore body.

No profits were forthcoming, and the lode deposits remained untouched. The mining inspector’s annual report for 1917 gives a pitiful return from six months’ work of two-and-a-half hundredweight (127 kg) of tin and wolframite concentrates, amounting to an estimated value of £12.

This final attempt at striking it rich was based on sheer speculation fuelled by rising prices rather than any firm evidence of tin in economic deposits. Perhaps, though, it sums up the blind optimism of the whole tin saga. Only a paltry tonne of cassiterite was ever recovered from the area—hardly comparable to the “smaller edition of Cornwall” that Professor Black had likened it to. Rakiura, New Zealand’s “land’s end,” never proved the tin Mecca that England’s was.

Ironically, the original gold miners got more tin than gold, and the tin miners more gold than tin. Concentrations of tin in the source rock turned out to be much lower than those found in the alluvial deposits and creeks draining the area, which were the only deposits of any quantity.

The much-sought mother-lode was a myth. The alluvial deposits were rich simply because cassiterite had been accumulating there for thousands of years, eroded from the ranges by the endless chafing of wind, water and ice. Today’s meagre cassiterite-bearing veins in the Tin Range are probably the remnants of a much more extensive vein system that has been worn steadily downwards over the eons (see sidebar, page xx).

The situation is analogous with that of the famed Otago Goldfields, where alluvial gold was fabulously abundant while the source lodes were scarce and had low concentrations of gold.

So, was Professor Black a charlatan, to set so many on a wild goose chase after a nonexistent resource?

More likely, he was an opportunist who jumped to an erroneous conclusion. Although some miners bore the professor a degree of malice over the whole debacle, it was hard to dislike the man. In an Otago Daily Times reflection on Black published in the 1940s, Gordon Parry writes, “Everything Professor Black undertook was done with flair and flourish. He had such enthusiasm for his subject that he regularly held open lectures at which he conducted experiments. The public flocked to them, not always from love of chemistry but from appreciation of the professor as a performer…. Wherever he went, he had a following, including his faithful assistant, Wully’ Goodlet, who was always as calm and organised as the professor was impetuous and erratic.

‘Bring me a thousand gallons of sulphuric acid,’ Black would bellow during an experiment, at which Willie would quietly get up and hand him the bottle which was right under the professor’s nose.

“Or, ‘I need 40,000 tons of chalk,’ he would cry, having filled an enormous blackboard with equations.”

In 1910, at the age of 74, the professor retired to Stewart Island with his wife, and Mason Bay became one of his favourite haunts. On one occasion he was a few days late in returning from his trip, and a search party set out to find him. No light at the homestead added to their fears, but they found him safe in bed. And laid over his blankets was a heavy door, which had come off its hinges.

“What’s wrong?” they enquired. “Are you afraid you’ll walk in your sleep?”

“Not at all. It’s a cold night,” retorted the professor, “and weight is conducive to heat.”

[chapter break]

During the early 1920s the odd prospector continued to poke around Port Pegasus, hoping to pick up a bit of metal. One of them was Carl Yunge”Big Charlie.” A Dane, Yunge was a giant of a man. His father had told him tales of the Dunstan gold rush of the 1860s in Central Otago, and gold fever lured him to the Antipodes. “I vanted some of vat jeller stuff, but I vanted adventures too.”

The late Bruce Nilsen remembered him. “A bit of a beeze, Buce” (he couldn’t pronounce his R’s), he’d say whenever a gale was blowing. Bruce’s brother Thor prospected with Charlie, and managed to scrape up enough gold for his wife’s wedding ring. “Big Charlie” made no money at Pegasus, but when he died it was a Viking’s funeral, his ashes scattered at his request in the tempestuous seas of Foveaux Strait.

Ted Carrington, former engineer for the city of Napier, arrived on the island in 1937 and made numerous trips to Port Pegasus. Probably the last of the tin miners, he blazed a more direct route from the southern end of the Tin Range via Scollay’s Flat to Maori Bay. He stayed for months at Pegasus, and constructed a storehouse with the help of Peter McKellar. Together they packed tinstone down off the range, where it was picked up by Bill Thomson on the pride of Pegasus, his 21-metre ketch Ranui, built and launched there in 1936.

Among the items of the tin miners’ legacy was a pair of draughthorses, let loose once the rush was over. They made their way up onto the open tops, where, according to islander Roy Traill, they could get a decent feed, but could not return to the low country as the bridges deteriorated and tramlines became overgrown. One died, but the other hung on for several years—possibly the loneliest horse in the world.

[chapter break]

Today nature is reclaiming its own, with manuka and leatherwood regenerating in many of the burnt-over areas. The miners’ efforts are still evident in the form of mounds of spoil, a dam and race and a couple of deep drives set into the southern extremity of the Tin Range. Remnants of the 1912 venture include piles of tailings, bits of the sluicing gear and the wooden tramline from Diprose Bay to a dam at the head of McArthurs Creek.

It is perhaps strange that no tin miners reported sighting kakapo, despite the fact that the workings were concentrated in the area where kakapo were rediscovered in 1977. One theory is that kakapo numbers increased once the miners left, due to an improved feeding habitat. Kakapo in Fiordland showed a preference for foraging in the regenerating bush of avalanche paths, and the burnt areas around Port Pegasus reverted to assemblages of manuka scrub and cushion moor with scattered swampy areas—veritable “kakapo gardens.”

As it turned out, the miners were more endangered than the kakapo, but the most ardent of them seem never to have lost their hopes of striking it rich. In a poem he titled “Tintinnabulation,” bush bard Swain ended with the words:

Invercargill is made. Stewart Island’s the Bank.

Lots of tin is there lying to credit

And Black is the man we’ll all have to thank

For it’s TIN just as sure as he said it!

Tin it was, as sure as he said it, but not enough. Stewart Island never became a bank. Invercargill was made not from tin but the sheep’s back and the cow’s udder.

And the Tin Range? It remains—brooding and windswept, yet with its own special allure. Its hills yielded little measurable wealth to our forebears, but they have perhaps granted us all a greater gift with the rediscovery of kakapo in the area.

As for the effulgent praise and speculation over the richness of the field—a paean of exaggeration which could not be tempered by the hard data of scientific analysis—it just goes to show that hope never listens to the voice of reason.

The poet Denis Glover had it right:

You should have been told

Only in you was the gold.