Moruroa protest

In June 1995, the French government announced it would carry out eight final underground nuclear bomb tests at Moruroa atoll before ratifying the UN’s comprehensive nuclear test ban treaty. The announcement provoked a storm of protest around the Pacific. Greenpeace sent ships to the island, protest marches and riots took place in Papeete (left), and a peace flotilla accompanied by the naval ship Tui headed to Moruroa from New Zealand. Marty Taylor sailed aboard Chimera and relives the protests of 10 years ago.

Sometimes having no experience of something helps convince you of its merit. My decision to sail through the Southern Ocean’s Roaring Forties in winter, when hurricane-force winds are at their most frequent, turn left several thousand kilometres from home, head north to an atoll where the inhabitants were detonating nuclear bombs, then come home and make a documentary about it depended on this sort of wisdom. I had never sailed offshore and I had never made a film, but I was convinced I could do both.

New Zealanders learned long ago that if they got into trouble, rescue from their colonial outpost was not to be relied on. To survive their isolation, they developed a fierce independence and versatility. As a result, right-brain tradition was replaced by left-brain can-do. Forming a peace flotilla in response to French nuclear testing on the Polynesian atoll Moruroa was brave, innovative, pragmatic and a continuation of New Zealanders’ evolving tradition of ingenuity.

France’s announcement that it intended detonating a final series of nuclear bombs on Moruroa was issued in June, 1995, hard on the heels of tests by China. Their actions left me feeling annoyed, impotent and slightly numb. Believing there was little I could do, I put them to the back of my mind.

Later that month I was sitting at home in front of the wood burner, feet up, watching an interview with Green-peace anti-nuclear campaigner David McTaggart on 60 Minutes. Towards the end of the interview McTaggart invited New Zealanders to join him at Moruroa. Not being a sailor I thought it unlikely anyone would be prepared to take me. The next morning, I heard Manukau City councillor Barry Keon say on National Radio that he would make his boat, Tryptich, available to a “suitably qualified crew”, which again ruled me out.

At the time, I was studying the political context of New Zealand film and television at Auckland University. After lectures, Dan Salmon, a fellow student and holder of a skipper’s ticket, asked half-jokingly if I was keen to join the protest. I immediately said, “Yes, but…”, then listed half a dozen reasons why not to go. But I also said, “We might be able to make a documentary about the protest.” Richard Smith, the course tutor, was in the room and chipped in, “Sure, but you’re mad. All you can see at sea is sea, and that doesn’t make for interesting TV.” Unconvinced, I thought the matter over. I concluded that a documentary on the peace flotilla would fulfil my course obligations, and that, with a bit of bluff, I would be able to convince boat owners I had a useful skill.

Growing up, I had heard many anecdotes of nuclear weapons and witnessed military life close up. My father had been involved in British nuclear testing on Christmas Island and related stories of greasing up the fuselage of planes with goose fat—for protection from radiation when flying through nuclear mushroom clouds. He talked of the intense brightness of a nuclear explosion, of seeing the outlines of bones in his hands while covering his eyes during the flash.

When I was a boy during the Cold War, my family lived in Germany near the East–West border. Whenever sirens wailed at the base where my father was stationed, he would run out of the house. When I was told that the planes he worked on carried nuclear bombs, and that these could kill thousands of people and destroy whole cities, I felt confused and afraid.

As a teenager I followed, and felt proud of, New Zealand’s progression to its nuclear-free status. Later, at Otago University, I wrote about the country’s role in the World Court Project (an attempt to get a judgement from the International Court of Justice (ICJ), in The Hague, on the legality of nuclear weapons), the nuclear non-proliferation treaty, and the arms-reduction treaties between the United States and Russia. I had long believed that nuclear weapons were abhorrent and that their use, or the threat to use them, was inhumane and illegal, a belief subsequently reinforced by a unanimous decision by the ICJ on July 8, 1996.

The peace flotilla, however, was more than a protest against nuclear testing. It was also a reaction to French heavy-handedness and the bombing of Rainbow Warrior. To me France seemed, inexcusably, to be repeating past imperialist errors. I understood the arguments around nuclear deterrence but I didn’t agree with them. I believed nuclear testing in the Pacific was a contradiction of the French credo of liberté, egalité and fraternité.

[chapter break]

The atolls of Moruroa and Fangataufa lie in the south-eastern sector of the Tuamotu Archipelago of French Polynesia. Like many atolls in the region, they were formed around 10 million years ago following the emergence, and subsequent erosion and submergence, of undersea volcanoes. As the volcanic cones sank back beneath the waves, coral growth on them kept pace with their descent, resulting today in a cap of calcium carbonate, or limestone, 400 m thick.

In the mid-1960s Moruroa was selected for atmospheric testing because “only” 5000 people lived within a 1000 km radius of the atoll. Within the danger zone round the test site, which was to be kept free of planes and ships during each explosion, were seven inhabited atolls. Tureia, with a population of about 60, is the closest-in of these, lying approximately 120 km north of Moruroa. Even after the French reduced the radius of the danger zone, Tureia remained within range of possible exposure to atmospheric fallout.

In 1963 the majority of the nuclear powers signed the Limited Test Ban Treaty, which stipulated that signatories were not to conduct nuclear tests under water, in the atmosphere or in space. President de Gaulle refused to sign for France, even after US President Kennedy offered to help his country establish an underground testing programme. The French began testing in the Pacific on July 2, 1966. From 1966 to 1990, 167 nuclear tests were performed, 44 of them atmospheric.

In 1973 the New Zealand Labour government, spear-headed by Attorney General Martyn Finlay, challenged (with the governments of other nations) the legality of French atmospheric testing at the ICJ. The French government bowed to pressure from Pacific and South American countries. Future tests would be under ground, and Fangataufa would be the test site. The last atmospheric test was conducted on September 15, 1974, the first underground test on June 5, 1975.

After several tests on Fangataufa, testing returned to Moruroa. In 1981, probably because of damage to the atoll’s outer rim, detonations were carried out in shafts drilled nearer the centre of the atoll than those used earlier. Many tests later, a senior French officer deemed Moruroa too fragile for the more powerful explosions. In 1987 the Cousteau Scientific Mission to Moruroa confirmed this view, having discovered signs of subsidence on the floor of the lagoon. France announced that larger tests would henceforth be conducted on Fangataufa to avoid more serious damage to Moruroa. This declaration was later withdrawn and testing continued solely on Moruroa until 1995.

After more than 120 underground tests, Moruroa has in effect become a nuclear waste dump. To be secure, such a site should meet certain criteria. The chamber should be watertight, there should be no escape channels for fission products, and the absorption of radionuclides by the surrounding rock should be very high. In all these respects, Moruroa is less than ideal. The atoll, being largely porous, is water saturated, while its basalt platform has been severely fractured and fissured, creating channels that might allow the leaching of fission products. To top it off, the French authorities have themselves estimated that the absorption coefficient of the basalt is very low. The claim by a Greenpeace mission in 1990 that it had detected caesium-134 in the sea around the atoll suggested that Moruroa was starting to release radioactive waste.

Several scientific investigations have examined the impact of underground testing on the integrity and condition of the atoll. Most frequently cited are a study by a joint Australian, New Zealand and Papua New Guinean mission in 1983 and the Cousteau study of 1987. In both instances visiting scientists were given authority to carry out their investigations and found damage to the structure of the island, including fissuring and subsidence.

[chapter break]

I thought it reasonable that people go to Moruroa to protest against the damage that had been done. At the same time, I considered protesting would be futile in that I didn’t believe it would stop the testing; to do nothing, though, seemed an act of complicity. I justified my going in another way, too: I thought I could provide a distinct voice. Although many who joined the peace flotilla sympathised with Greenpeace, everyone I spoke with shared the belief that it was an expression of New Zealand sentiment, not just Greenpeace ideology. In the end I decided to go because I knew I could articulate that sentiment.

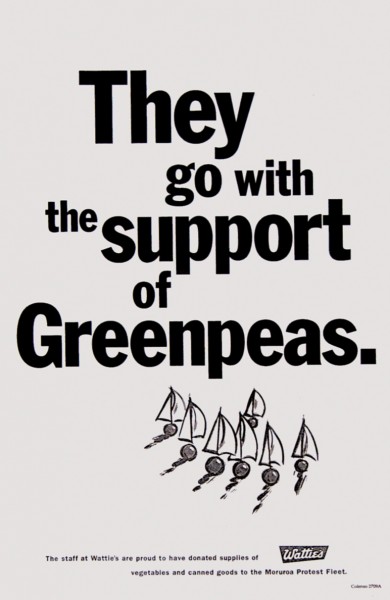

As the 1981 Springbok tour had divided the country, so the peace flotilla united it. Soon after Barry Keon had volunteered Tryptich, other boats and crews from around the country materialised. Dan and I secured a place aboard the single-masted steel-hulled yacht Chimera, from Greymouth. Chimera joined Joie, Kela and New Zealand Maid in a mini-flotilla based in Wellington.

Dennis Johnson, a non-sailor with a knack for words, coordinated the fundraising for the capital’s little fleet.

“There were some grotty aspects to the job,” he recalls. “Some of the media people wanted to corner the market and cut out other stations. This sort of commercial carry-on really gave me the tomtits. I just about decked a few of them.”

Despite such negatives, TV exposure really kicked off the fundraising campaign. People everywhere offered their support.

“Someone would ring up and say ‘I’m an artist. I want to paint all the boats, have an exhibition and donate all the proceedings to the flotilla.’ I would say, ‘Great, but can you organise this, mate, because we can’t.’ The Body Shop one day said, ‘We’ve collected $5000.’ It was really gratifying knowing people were swinging in behind us.”

Shortly before departure Dan and I had a few last-minute jitters. Gary Shearer, the skipper of Chimera, was a West Coast gold-miner with a penchant for guns and palletloads of beer. We, on the other hand, were crusading political-science students from the big city cushioned from the abrasive realities of such an existence. We hoped the clash of cultures would be overcome by our common goal. After all, the boat was strong, the three other yachts were to keep her close company and the other crew members were decent types. The day before sailing, however, our confidence in the boat was dented when we dry-docked her only to discover that two of the three bolts holding the rudder in place had sheared off during the voyage from Greymouth to Wellington.

The flotilla sailed from Wellington on August 24, 1995, after a civic farewell, accompanied by a fleet of well-wishers. Joie headed directly for Cook Strait and we didn’t see her again until we were just hours from Moruroa. The rest of us tied up at Eastbourne, where we stowed supplies and readied ourselves for an early-morning sailing. Westerlies carried us past Cape Palliser and out into the Pacific. As the coast disappeared and sea and sky merged, I felt strangely at ease.

[chapter break]

Winds are measured using the Beaufort scale, which runs from 0 to 12. Zero is calm. At the other extreme, hurricane-force winds reach more than 70 knots and turn the sea white with driving spray.

By the morning of our second day at sea, the wind had increased to 20 knots, or “fresh” on the Beaufort scale. This was exciting. Our sails were full, the bow crashed into the waves, sending sea spray whistling the length of the boat, and our protest flags flew taut. But the wind kept building and by mid-afternoon had progressed through “strong breeze”, “gale” and “strong gale” and on to “violent storm”. With gusts of 65–75 knots, conditions were no longer comfortable. Dennis Johnson later described the wind as “pretty grunty”.

We took down all sails, hoisted a small storm jib to keep us on course, and put out a sea anchor. The sea was running at about 14 knots, and the anchor was to slow us so that the swell rolled past, preventing the boat from sliding down the wave faces and slewing beam-on to the breaking crests. The wind was so strong that we had to give the anchor extra drag using whatever we could find, including some rope and an old car tyre.

The swell had grown from a couple of metres’ height in the morning to humungous in the afternoon. Having no point of reference and no sailing experience, I couldn’t even guess at their size. Later, consensus among the Wellington contingent put it at 12–16 m—which translates roughly to 30 m from peak to trough. The crests were being torn by the wind so it wasn’t a smooth roller-coaster ride. Rather, a wall of boiling white water would bear down from astern, then bash into us.

We steered in shifts. The job of the person on the helm was to keep hits from the side to a minimum. After each hit, I’d get a flashback to the three bolts holding the rudder in place. I didn’t need to imagine the stresses the boat was under—I could hear, feel and see them. The mast would bow and groan; the rigging howled. Being inside Chimera was like sitting inside a wheat silo while someone beat the outside with a baseball bat.

Quiet was probably the most worrying “sound”. Occasionally a gust was so strong it would drive us ahead of the swell, causing a sudden hush inside the cabin as we careered down the wave face. Wallowing in the trough, we would wait for the white water to crash into us as the swell caught up. Each time it hit, the boat would lurch over to one side before her hefty keel righted her again. And all the while there was the debilitating nausea unique to seasickness. After six days of strong gales, storms, violent storms and hurricane-force storms, the weather system passed. We were all bruised, battered and exhausted but making good progress; and, despite the conditions, the other Wellington boats, including Joie were close by.

The first piece of disturbing news came on September 1, when the French seized MV Greenpeace and Rainbow Warrior II. We all knew that if Green-peace suspected a test was about to go ahead, they would sacrifice one of their vessels to draw attention to the fact in the world media. When we heard that both vessels had gone—and with them all the telecommunications gear that was to have broadcast the flotilla’s presence to the media—we felt let down. Participants were divided into two camps: those who blamed France, believing it had broken international law by seizing ships in international waters, and those who blamed Green-peace, believing it had made a tactical error. But regardless of who was to blame, the French had gained the upper hand.

We received this news one or two days into our second storm system. It was less intense than the first, but again we reduced our sail power to a small storm jib and threw out the sea anchor. I was on the 2 a.m. to 6 a.m. watch. By this stage of the voyage I was tuned-in to the idiosyncrasies of Chimera in stormy seas, but 10 days of sleep deprivation, heightened anxiety and a diet of Fruit Bursts—the only thing I could hold down—had taken its toll on both body and mind.

On one of my watches I noticed there was very little resistance from the rudder and the speed indicator was surging to 16–20 knots. All I could think of was the three bolts that were meant to be holding the rudder in place. The rest of my watch was punctuated by moments of dread, when I convinced myself the rudder had gone. For the most part, though, I suppressed this fancy by telling myself I was being paranoid. I even managed to let myself enjoy the sensation of speed and the solitude of the night.

During the day you can see the waves behind you and where you are in relation to them. At night, in a dimly lit cabin, you are blind beyond your instrument panel. In these circumstances, the combination of tiredness and inexperience proved almost disastrous. I blocked out the readings of the instruments. I was unable to make sense of them and thus unable to rationalise our high speed and the low rudder resistance.

What had happened was that the sea anchor had become unshackled, so Chimera was glissading down the waves. A skilled sailor would have been able either to diagnose and fix the problem or maintain control in the breaking waves. If it had been daylight, I would probably have realised what was happening. In the dark, though, I was unaware of the danger and sailed like this for around an hour. Then everything went silent.

Moments later we were side-on, deep in a trough. Chimera waited. Seconds later a 12–14 m breaking wave T-boned us and we were engulfed by a massive wall of water. Thousands of kilometres from home, no hope of rescue, and it felt as if we had been hit by a speeding locomotive. I was thrown out of my seat and smashed into the wall opposite. I clawed my way back to the helm amidst flying papers, cameras, clothing and anything else that wasn’t tied down. Water poured in through the external door. Bodies writhed on the floor, having been flung out of their bunks. Through one porthole was the ebony sheen of black water against glass. Through the top window I could see the boil and hiss of foaming white water. The chaos increased as everyone rushed into the cockpit.

After the sideways whip of the initial impact, the roll slowed as the keel struggled against the rush of water. Mast and storm jib resisted. Chimera held her position as if deciding whether to keep rolling or make the effort to recover. Suddenly the wall of white water had rushed past and we were whipped upright on the back of the wave. Again, bodies were thrown around. I regained control of the boat. A quick diagnosis was made. We threw together a makeshift storm anchor using a small sail, shackled it firmly to the stern and threw it overboard.

The storm lasted another day or two, and no one mentioned the incident.

[chapter break]

On September 5, 1995, at 21:30 GMT, the French carried out the first nuclear test. Our overwhelming feeling was not of anger but of sadness for the environment and for the people of the region, an emotion that was amplified two days later when we heard that during anti-French riots in Tahiti there had been extensive damage to people and property. We were still a week away from Moruroa, and the mood aboard Chimera sank to its lowest point. Had we left our run too late? Were our efforts to prove worthless?

When we were a day out from Moruroa, a French Learjet completed a fly-by 100 m above our mast. Later, a military helicopter buzzed us and took photos of the boat and crew. After 19 days alone at sea, it was odd being the centre of attention.

Remarkably, after 4500 km and two major storms, the Wellington boats were within a few hours of each other. We regrouped into a mini-flotilla, unfurled our protest flags and sailed proudly towards the horizon and a rendezvous with Tui, the RNZN survey vessel sent to bear witness to events and support the flotilla. Her captain, Lieutenant Commander John Campbell, came aboard, welcomed us to Moruroa and told us what to expect.

Tui had been instructed by the Bolger government to assist the flotilla in the event of an emergency, but Campbell decided it was better to pre-empt likely problems by supplying the yachts with extra water and fuel. Dan and I were invited aboard the survey ship, where we were fed vegetables, had a shower and watched a seismic trace of the first test.

After the loss of MV Greenpeace and Rainbow Warrior II, the tall ship R. Tucker Thompson became the heart and nerve centre of the flotilla.

Before leaving New Zealand, each boat had been given a nautical map of Moruroa and Fangataufa overlaid with a street map. When we wanted to meet up, instead of giving each other degrees longitude and latitude, we would agree to meet on, say, the corner of Queen Street and K Road. Our skippers could pinpoint the spot, but the French couldn’t.

Whenever the boats came together, it brought relief from the drudgery of sailing. Dan and I set ourselves up on Tucker Thompson with a dodgy microphone and cameras and went about interviewing and talking with as many of the flotilla crew members as possible.

At first most of the boats were reluctant to venture into the 12-mile exclusion zone, and we, too, kept our distance. Photina, though, had navigated her way to Moruroa without GPS, and, manual fixes being less reliable, she inadvertently strayed in and out of the exclusion zone on an almost daily basis. Tui would warn boats by radio as they approached the boundary, but after a while we all became a lot more relaxed and regularly crossed into forbidden waters.

On one rendezvous, Dennis joined us aboard R Tucker Thompson for one of the lighter moments of the voyage. He asked if any of the skippers had tin foil and condoms in their stores. Everyone looked bewildered. Mischievously, he started to explain: “We could blow up the condoms and fill them with tin foil.” Everyone looked at him quizzically. “The French don’t like us crossing the line, right? We could release lots of condoms and let them blow inside the 12-mile limit.” Everyone remained attentive. “The aluminium inside the condoms will look like boats on their radars.”

Suddenly everyone understood. The French had nine patrol boats and frigates ready to pounce should we stray far into the exclusion zone, but if we released hundreds of floating aluminium-filled condoms they wouldn’t be able to distinguish between yacht and condom. They would have to check out every radar blip to see if we were breaching the boundary. As a result, we would be able to enter and leave the zone without being molested.

This type of game-playing was essential because tedium was generally the order of the day. Games helped maintain morale and made us feel as if the balance of power had tilted in our favour.

One of the more significant protest actions was planned to take place on September 16. Two members of the Tahitian independence movement Hiti Tau joined us aboard Tucker Thompson. One was a labourer on Moruroa, the other had ancestral links to both Moruroa and Fangataufa. They intended paddling to Moruroa in a traditional piragua, or outrigger canoe. Their aim was to highlight the lack of medical supervision of past and present workers on Moruroa.

Regular reporting of French Polynesian health statistics ceased in 1966, the year nuclear testing started. From 1966 to 1980, the head of the French Polynesian health service was a general appointed by the French government. Only with his replacement by a Tahitian civilian was a register of cancer deaths opened. According to International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War, attempts to determine trends in cancer rates and in the occurrence of congenital abnormalities are pointless because data collection has been so poor. But if the cancer rates among people exposed to fallout downwind of test sites elsewhere in the world are used as a guide, there is reason to expect rates among the inhabitants of islands near Moruroa, and among the 13,000 Polynesian workers on Moruroa itself, to be high.

Aboard Tucker Thompson, preparations for the piragua protest began before dawn. During launching, the outrigger snapped and the canoe started to sink. Several of Tucker’s crew dived in to retrieve the flimsy hull. Soon after dawn, repairs had been made and the two men paddled into the exclusion zone. Moments after they had crossed the line, two humpback whales joined them and began breaching and slapping the water with their tails. We were amazed at the timing of their appearance. Later, in Papeete, one of the men said he had dreamed of the encounter and that it was a good omen. It was the second encounter with whales for the crew of Chimera since leaving New Zealand, and everyone present was thrilled and stunned by the performance. The men made it onto Moruroa.

Among sailors there are many traditions and conventions, and a code of ethics, that are lost on land-lubbers. All exchanges between vessels are conducted in a courteous manner. With many years’ sailing behind him, John Simpson, the skipper of Photina, was well-versed in mariners’ rules of engagement. He was also fluent in French. Both attributes elevated him in the eyes of the French naval officers.

When the flotilla arrived off Moruroa, each boat was given a letter from Vice-admiral Philippe Euverte, welcoming the sailors and outlining the rules concerning French territorial waters and the consequences of breaking them.

“We hatched a plan,” Simpson recalls. “We thought we would try to see the boss and tell him to stop testing. So we told the French we would accept their letter if they would accept ours. Having sent the letter I asked for a reply.”

Whenever Photina made contact with the French it was normally because she was inside French waters. “They would say, ‘You are in French territorial waters,’ and I would say, ‘Have you got a reply to my letter to the admiral yet?’ with comments like, ‘Your admiral is a polite gentleman, he has manners. Has he a reply for me?’”

Simpson was contacted by the admiral’s frigate, La Railleuse, inviting him to accept a reply to his letter. I joined Simpson to pick up his mail. I expected either a roasting or a frosty reception from the crew of La Railleuse when we pulled alongside. Instead, we were greeted with cheers, words of encouragement and whistles of support from the ratings and conscripts. Even the officer who delivered the admiral’s letter was very respectful.

The admiral regretfully declined a personal meeting. He had written: “I am very sorry I won’t be able to meet you. I am not in Moruroa at the moment. I was only there for the actual time of the first test and now I am back in my normal office in Tahiti. If you are ever in Tahiti it would be nice to see you and chat as old sailors.”

Most of our interaction with the French was cordial. Not only did we receive letters of welcome, but radio communication was generally conducted with good humour, too. Tension was greatest when we were buzzed by helicopters or Learjets, or when the frigates came close. Anyone who has crossed paths with the Interislander or a cargo ship while sailing a small yacht will understand. A distance of 100 m, although safe, feels intimidatingly close.

[chapter break]

Before leaving New Zealand, Dan and I had collected hundreds of letters from primary-school pupils. We had promised to do our best to deliver them to President Chirac or the admiral. Aboard the Greenpeace ship Manutea were several recreational surf skis. We planned to use these to get to Moruroa and deliver the letters.

Back on R Tucker Thompson, master Russell Harris wasn’t happy about the idea of paddling for 12 miles on the open ocean with little in the way of navigational guidance, then landing on an open reef. He thought it dangerous and would accomplish little other than make us personae non gratae with the French and get us deported.

I decided to remain behind and document an attempt by Tureians to reclaim Moruroa. But Dan was bent on going, having been inspired by the Hiti Tau activists. “Watching them paddle off at sunrise with the French warships hovering around was the moment I decided I was going to paddle in too. It was frustrating sitting out there thinking ‘Am I doing enough? I’ve come all this way and I’m just sitting here.’”

Daniel Godoy, a member of Tucker Thompson’s crew, decided to join Dan. Their double surf ski was small and plastic so didn’t show up on any of the French radar.

“We paddled around in the lagoon for a while looking for someone to talk to. Eventually we paddled up to three legionnaires playing chess and sunbathing. The soldiers immediately went into a tail-spin. One must have called their superiors because a helicopter turned up with military police and they were saying, ‘If you don’t tell us what boat you came from, you will face 15 years in gaol.’”

After a night of good-cop/bad-cop interrogation on Moruroa, neither Dan nor Daniel had any idea of their captors’ intentions. In the end they were driven to the airfield and flown to Papeete, where they were released.

On the way to the airfield they noticed the scars of past tests. On July 25, 1979, a 120-kiloton bomb had become irretrievably stuck halfway down its 800 m-deep shaft, but officials had elected to detonate the device anyway. The explosion had caused major slumping of more than a million cubic metres of coral and set off a small tsunami.

Before the French occupation of Moruroa and Faungataufa, the Tureians used both atolls, moving from one to the other to allow resources to recover. Tureia itself is generally upwind of Moruroa, and the French planned to conduct atmospheric tests when winds were favourable and would carry fallout away from the atoll. They nevertheless built large steel bunkers there to protect the inhabitants, and the island was subject to fallout on several occasions. It was against this backdrop that Greenpeace offered the Tureians an opportunity to highlight their situation by making a return to Moruroa and laying claim to their ancestral island.

I interviewed the Tureian chief through an interpreter. He explained that his people wanted to return to the atoll and wished the French to recognise them as its rightful owners. He also spoke of their poor health and economic status.

With the help of David McTaggart and other Greenpeace activists, the Tureian and Vanavanan chiefs Vanavana also lies within the atmospheric-testing danger zone—had written a letter to President Chirac. The Tureians wanted Greenpeace to take them to Moruroa so they could pass the letter to Admiral Euverte and ask him to forward it to the head of state.

Before the delivery party’s departure, McTaggart read a message to the French over VHF radio. After outlining the Tureians’ complaints, he announced their intentions: “Some of the Polynesians will sleep on the shore of the atoll peacefully with no demonstrations and then we will leave peacefully, as we came. We trust that you will respect the rights of the people of Polynesia. Many of those with us today have families born on Moruroa.”

[chapter break]

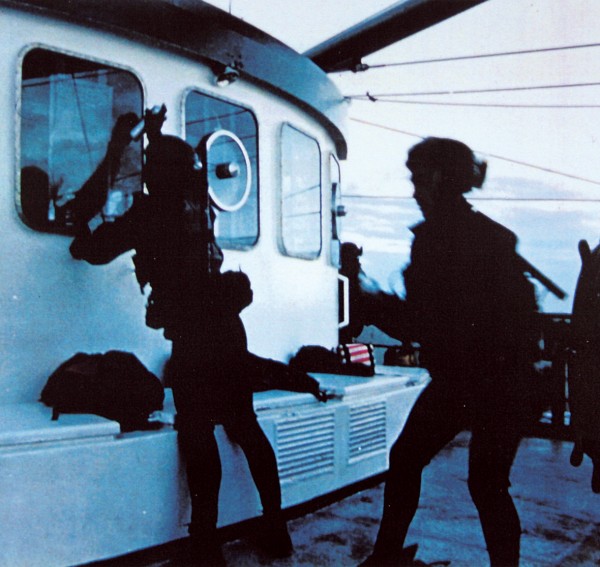

At 2 p.m. on September 26, I crossed into French territorial waters on the yacht Vega with 21 Polynesians. I remained aboard for a mile before I was picked up by zodiac and returned to Manutea. I climbed to the top of the mast, harnessed myself to one of the spreaders and watched as frigates and helicopters circled Vega. When she was about three or four miles inside the exclusion zone and beyond the range of my video camera, commandos boarded her.

Even without the boarding, I knew I had a good story. But I was 1200 km from Tahiti—a good week’s sailing at least—and I knew that my footage would be old news in two or three days. Greenpeace decided that the pictures I’d taken had significance for their campaign so decided to pay $US10,000 to fly a small twin-engine plane to pick me up from Tureia. We had 14 hours to sail 100 km to Tureia. Could we do it?

I jumped aboard Joie and we headed north towards the atoll. Darkness fell a little after 6 p.m., and we spent the night keeping the sails full and sailing hard. To my delight, Dennis and Lynn Pistoll of Joie had picked up a couple of dozen large bottles of Tahitian beer from the Greenpeace supply boat. It wasn’t cold but it tasted like impending freedom. I had done what I had set out to do and would soon be able to return home. The three of us spent the evening singing, laughing, looking at the stars and talking about not much. But I wasn’t free yet: a French patrol boat sat off our bow, far enough away for us to relish the moment but close enough to let us know we were being watched.

The first sign of an approaching island is the smell of vegetation. Before I saw Tureia I caught the scent of frangipani on the air. We reached the south side of the atoll by 6 a.m., three hours before the plane was due. It was great to see and smell greenery again. We sailed up the east coast, unsure of where we could land. By 8 a.m. we had rounded the northern tip, and we were sailing back down the western side when we spotted a tractor, several small boats and a boat ramp.

I was concerned that French surveillance had spotted me filming during the Tureian event and that this was the reason Joie was being shadowed by a patrol boat. I feared that it may have radioed ahead to gendarmes on Tureia and told them to confiscate my tapes. As a precaution I had relabelled the cassettes, sealed them in a water-proof bag and buried them among my belongings.

To land meant negotiating a narrow gap in the reef, which had a 2 m swell breaking on it. Dennis and I jumped into Joie’s tiny tender and started rowing towards the breakers. Fortunately good sense prevailed and we decided it would be safer for me to swim ashore.

We paddled back to Joie, where the talk turned to my getting dashed on the rocks and becoming shark fodder. Brimming with false confidence I prepared to dive in, but in the nick of time Dennis noticed a couple of islanders towing a boat down to the shore. They sped out through the reef and offered me a lift ashore. Just as we were surfing the boat up to the ramp, I saw a gendarme in dark blue fatigues pull up in a white Toyota 4WD troop carrier. Fear of having my tapes confiscated came flooding back.

I thanked the men who had picked me up and, with an assertive swagger that belied my misgivings, strode toward the gendarme with my hand extended. I know very little French but I instantly understood the message on his baseball cap, Non a la bombe. My concerns dissolved as he stretched out a big welcoming hand. He saw my small stills camera and motioned that he wanted it. Slightly confused, I complied. Then he gave it to one of the men who had brought me ashore and asked him to take a photograph of us. He put his arm round me and gave a great big smile for the camera. He proceeded to take me on a tour of the island and gave me mango and coconut to eat at his house. Toward the end of the tour we visited a steel nuclear-fallout bunker. The rusting post-apocalyptic relic seemed totally out of place and was a frightening reminder of the past.

The plane landed at 9.30 a.m. and I was greeted by a member of Green-peace. It was a very weird exchange, almost as if we were completing an international drug deal. I handed him the tapes and he gave me a lift that would return me to normal life. We dipped our wings to Joie as Lynn and Dennis sailed back into the fray.

On the plane, I was told that the French had denied there had been any Polynesians aboard Vega. Their press release stated that David McTaggart and another Greenpeace activist, Chris Robinson, had been the only two people aboard. I assured my Greenpeace helper I had everything his organisation would need to prove that Tureians had been aboard.

The truth, though, was that I wasn’t absolutely sure the camera had worked. Dan had taken our original camera to Moruroa, while I had received a new Hi8 camera from Papeete only the day before. The operating systems of the two cameras were slightly different, and I’d decided I couldn’t afford to practise with the Hi8 because it had come without any recharging equipment and only two charged batteries. On the day of Tureian action I’d been pleased with my decision because both batteries had gone flat while I was rolling. This meant I’d been unable to alleviate my concerns about whether the camera had worked by rewinding and reviewing the footage in the viewfinder.

An hour into the flight we descended and landed at an atoll called Anaa to refuel. We had about half an hour to wait so I walked to the lagoon and went swimming. I thought that was it. No more anxiety. No more discomfort. No more stress. I lay on my back, floating in a tropical paradise.

[chapter break]

Papeete airport still bore the scars of the riots that had taken place after the first test on Moruroa. After landing I had to clear customs. I thought this would be a mere formality because the footage was on its way to Reuters office in Papeete with Greenpeace and I had nothing with me that could cause trouble. But I found myself the target of hostility from both customs officials and gendarmes. Then I realised I was wearing an anti-nuclear, pro-Tahitian independence T-shirt. Life improved when I changed shirts.

A mobile phone lent to me by Greenpeace rang while I was sitting in a taxi stuck in rush-hour traffic. A panicked voice confirmed my niggling doubt: “There is no footage. There is nothing on the tapes. Reuters can’t find your images.”

Yet I was fairly certain I hadn’t made any mistakes. “Don’t touch the tapes,” I said. “I will come directly there and use my camera to download the pictures.” I was emphatic that I didn’t want anyone playing with the tapes.

My caller assured me that no one would touch a thing, but added, “Reuters have a deadline. The pictures have to be out in an hour.”

I was stuck in traffic, my preconception of Tahiti as an island paradise shattered. I had one hour to get to Reuters’ hotel, diagnose the problem and then edit a story. I sat in the taxi for half an hour, stewing. Then the phone rang again.

“Where are you?”

“Stuck in traffic but nearly there.”

Ten minutes later came another call, and five minutes later yet another. As we were now only a few minutes from the hotel, I sprinted the rest of the way. Reuters had converted a room into an editing suite. I hooked up my camera to their editing bench and put the tapes in the camera. I rewound. Pressed play. Held my breath. And let out a huge sigh of relief as the images rolled onto the screen in front of me.

All the major international news networks ran the story. That night the pictures I’d taken went out to the homes of people in every country in the world except France.

The final embarrassment for the French came the next morning at a press conference. Their officials had finally admitted that there had been Polynesians aboard Vega. However, they claimed that Greenpeace had deceived the islanders, who hadn’t known they were being used as political pawns. I was able to show the interview with the Tureian chief. This time a more powerful story was reported. The voice of a leader unknown outside Polynesia echoed around the world shortly after the French claimed he had been deceived.

Was the flotilla a success even though it didn’t stop the nuclear testing?For me—definitely. My only expectation regarding the flotilla was that it would bear witness to events as they unfolded and offer a dissenting New Zealand voice. It certainly did that. And I fulfilled my personal goal of sailing across the hurricane-tossed Southern Ocean to an atoll where the locals were detonating nuclear bombs, then coming home and making a documentary about it.