Lost & Found

New Zealand storm petrels were presumed extinct, then rediscovered in 2003, more than a century after the last sighting. But their breeding site—the focus of conservation efforts for any seabird—remained a mystery. Researchers went out to prove the old adage that a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush. Would a radio-tagged storm petrel lead them to the breeding site of New Zealand’s most elusive seabird?

Big seas, strong winds, tiny seabirds. Two of us perch in an inflatable dinghy, one moment riding high atop a three-metre swell, the next, deep within a trough. From the crests we can see panoramas of the outer Hauraki Gulf, raging with white caps, and our ‘mother ship’ lurching wickedly a hundred metres away. In the troughs, the air feels remarkably calm. We savour the shelter, then rise again.

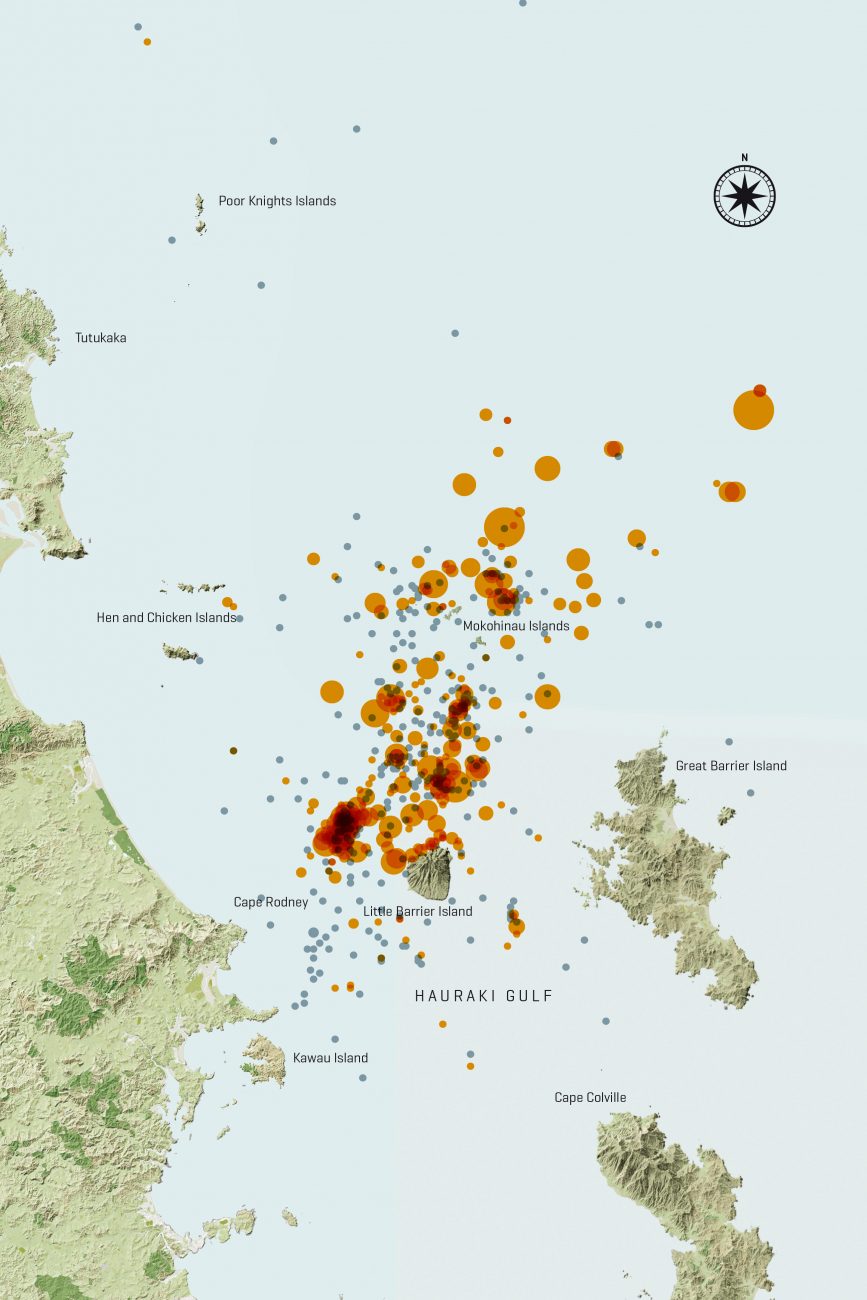

Our mission: to catch New Zealand storm petrels at sea and attach radio transmitters to these sparrow-sized birds, then try to track them to land. Any one of the many islands that are scattered about the outer Hauraki Gulf could be the birds’ breeding ground, which has remained unknown since they were rediscovered just ten years ago. The site, possibly still threatened by predators, should be the focus of conservation efforts for the species to ensure their survival.

A string of wild weather events has threatened to unravel our well-laid plans. A week earlier, in light airs, University of Auckland research fellow Matt Rayner and I caught five birds in one day. All were released with transmitters attached. At the same time, we managed to scramble ashore and install automated receivers high on two of Little Barrier Island’s headlands, despite big seas driving against the coast. Days of strong easterlies and an unrelenting sea have since given us little chance to catch and tag birds. We can’t even land to check whether those already tagged have been detected by the receivers, or to see if the systems are still running.

Eventually, frustration leads to desperate measures. We decide to head for the biggest island, hope for some sort of wind shadow, and try to attract birds to us. Attached to the stern of our inflatable is a berley bomb, a bag of fish offal releasing a slick of fish oil far into the distance. Our target birds, like all petrels, have a highly developed sense of smell, which they use to locate prey at sea. Soon Cook’s petrels glide low over our heads. One million or so of these birds breed on Little Barrier (Te Hauturu-o-Toi), and in January there are always large numbers about the gulf during the day. A few larger black petrels and flesh-footed shearwaters land close by and pick away at scraps of berley. Some smaller birds fly in. They’re white-faced storm petrels, close relatives of the birds we are seeking, and delightful company.

After years of spending time watching seabirds, you get attached to these delicate creatures. With wings outstretched, they use their long legs to bounce across the sea. Around our boat they appear to stand on tip-toes, picking away at the oil and bits of fish on or just below the surface.

[sidebar-1]

A shout. The crew on the bigger boat have seen something. We scan the waves from each wave crest. The wind has definitely got up. Then we see it, a pint-sized, black-headed bird zeroing in on us. It flies rapidly, swallow-like, and shows a flash of white as it banks—the signature turn of a New Zealand storm petrel. We lose it amongst the waves, then suddenly it crests a wave 20 metres away, still flying towards us, momentarily feeding with the white-faced storm petrels as we descend once again into a big trough. It flies past, then circles, coming in closer each time. Rayner is poised over the stern of the small craft with a net gun—a mist net fired with compressed air.

I’m keeping the boat steady, bow to the wind. A little flick of the oars and a nice swirl of berley is laid astern. The bird feeds, then stalls. It’s too far away. It circles, stalls again, and the net gun fires. We have a bird. In short order we scoop it up, net and all, stow the net gun and signal for the big boat. Once safely aboard (no easy task), we head to the shelter of Little Barrier and the only calm water for miles.

To the calls of bellbirds, whiteheads and kaka from the nearby shore, Rayner and the team weigh, measure and photograph the bird. Metal and coloured plastic bands are fixed to its legs for future identification, and a tiny one-gram transmitter is activated and attached to the tail feathers before being released. We repack the net guns and fill them with compressed air, ready for another target.

[Chapter break]

Just ten years before, almost to the day, the New Zealand storm petrel was thought to be extinct; it had not been seen for 108 years.

But in January 2003, that all changed. A group of birdwatchers off Whitianga spied a small black-and-white bird fly across the bow of their boat. Biologist Brent Stephenson snapped photos, and the ornithological world drew into a huddle.

Initially, the bird was thought to be either a black-bellied or white-bellied storm petrel. But Alan Tennyson, fossil curator at Te Papa and an expert on New Zealand’s extinct birds, raised the possibility that this was the ‘extinct’ New Zealand storm petrel, a species known from only three specimens collected in the 1800s, all held by museums in Europe.

Eleven months later, in November 2003, a black-and-white storm petrel was glimpsed just north of Little Barrier during another bird-watching trip.

More sightings followed, and this enigmatic black-and-white storm petrel became the focus of an ornithological frenzy.

Were these birds really New Zealand storm petrels? Photos, even in this age of high-resolution digital cameras, weren’t enough to satisfy the scientific community. What was needed was a bird in the hand, and it wasn’t until the night of November 3, 2005, that this opportunity arose, in an unexpected way. A bird flew onto a fishing boat sheltering from a gale close to Little Barrier. By coincidence, the fisherman was an ex-New Zealand Wildlife Service officer, Geordie Murman, who instantly recognised the bird as something special. He put it in a box and got word out late that night.

Next morning, Richard Griffiths, a biodiversity officer with DOC at the time, braved 40-knot winds aboard a boat to reach the island. The bird was studied, measured, weighed, banded, photographed and released.

Interest in the New Zealand storm petrels exploded. But catching small, fast-moving birds at sea would always present a major challenge. Long-handled hoop nets were tried, but the birds evaded them easily. The idea of rigging mist nets between two boats was suggested, then dismissed as unmanageable by those who know boats. Retrieving all manner of seabirds caught in a net that could be submerged one minute or raised skywards the next was far too risky.

The solution came during some Christmas party shenanigans with a spud gun. Griffiths hit on the idea of developing a net gun similar to those used in the days of live-deer capture. Nets were stitched together with four projectiles attached to the corners. These were fired from separate barrels, taking the net out with them. Subsequently, Harvey Carran, a Warkworth farmer and handyman, refined the prototypical “Griffo Gun” using compressed air as the propellant and firing first from adapted propane cylinders, then from guns made of a high-pressure grade of PVC pipe. The resulting guns have a range of about 15–20 metres.

DNA analysis of three birds caught in 2006 with the net gun confirmed what ornithologists suspected: that the birds seen at sea in northern New Zealand waters were New Zealand storm petrels, the same species as the original museum specimens. However, speculation remained as to whether the birds were breeding on one of the Hauraki Gulf’s many islands, or were merely visiting New Zealand waters and breeding elsewhere. Could they, in fact, be rightly called ‘New Zealand’ storm petrels?

[sidebar-2]

Ground searches were attempted in 2006 and 2007 with the hope of finding breeding birds. Attention focused on the Mokohinau Islands, which lie at the heart of the area where the storm petrels were being observed. Small seabirds such as storm petrels, diving petrels and small shear-waters are extremely vulnerable to predation by rats, so rat-free islands were at the top of the list of candidate sites. The Mokohinaus include stacks and islets that have always been rat free, and in 1990 and 1997 rats were eradicated from the larger islands of the group. The island group was also the source of a tantalising record from the 19th century. Andras Sandager, assistant lighthouse keeper in the 1880s, published a set of bird notes for the islands that included a description of a storm petrel that, in retrospect, could have been a New Zealand storm petrel.

One of the techniques pioneered in the Chatham Island taiko project—another successful rediscovery of a previously ‘extinct’ seabird—was employed by the late Mike Imber on the Mokohinaus. It involves using a floodlight to shine a beam of light into the night sky. Seabirds of many species are attracted to the beam. Using a hand-held spotlight, individual birds can—with skill—be drawn to the ground and caught. In January 2006, on a very stormy night on Burgess Island, two researchers sighted a New Zealand storm petrel in the cone of light and managed to manoeuvre it down to head level before it flew away. For a long time this was the only record of a New Zealand storm petrel seen over land. But no evidence of breeding was found, so the focus shifted to other islands.

Historically, the incidence of kiore and cats on the cliffs of Little Barrier Island was thought to have been less than in other parts of the island, so feasibly a small storm petrel population might have survived there. And the Poor Knights Islands, further north, are believed to have always been rat free. Channel Island, in the Colville Channel, was something of a mystery ecologically. There were plenty of options.

Automated sound recorders were used to try to detect New Zealand storm petrel calls—a challenge, as no one knew what these sounded like. Many hours were spent sifting through the recordings to see if something different from known bird calls had been picked up. Although New Zealand storm petrels were not detected, this work had the benefit of providing up-to-date information on seabird breeding on these islands, and a massive database of seabird calls and other nocturnal sounds has been created.

In 2009, with a grant from DOC’s Data Deficient Species Fund, another attempt was made to catch birds, attach transmitters and track them, but it was hit and miss.

In October, one party spent five days on the water and failed to catch a single bird. In November, another group headed out, and after four days, no captures. On the fifth day, we caught five.

Transmitters were attached, and the Navy took two of our team aboard one of its inshore patrol vessels to scan a number of islands in the outer Hauraki Gulf. Automated receivers were set up on Little Barrier, Burgess Island in the Mokohinau group, and on one of the Poor Knights Islands. But none of the birds were tracked back to land. The receivers detected nothing.

For two years, the search was in limbo. The New Zealand storm petrel’s conservation status remained ‘data deficient’, though they continued to be seen at sea.

By 2010, a group of seabird ecologists including Matt Rayner, Graeme Taylor, Steffi Ismar and me realised that a great deal of research needed to be done on seabirds in the Hauraki Gulf. We secured funding from the Auckland Regional Council to undertake research on shearwaters, petrels, storm petrels, little blue penguins and Australasian gannets. With this impetus, Rayner and I renewed our attention on New Zealand storm petrels.

We focused particularly on the timing of breeding. Eleven New Zealand storm petrels had been caught at sea between October and early January, but none had bare brood patches on their bellies—a tell-tale sign of breeding condition. (With petrels, both male and females share incubation and chick-rearing duties, and both will develop bare brood patches just prior to laying. The bare brood patch develops when the skin of the bird’s belly loses its underlying insulating down, though it remains hidden by body feathers. Through the brood patch, the warmth of the bird’s body is transferred to the egg during incubation and to the chick for the first few days of its life. By studying the development of the brood patch from before egg-laying to re-feathering—during or after chick-raising—researchers can determine the timing of breeding.)

Our conclusion: either the storm petrels didn’t breed in the Hauraki Gulf—which would have been surprising, given their strong fidelity to the gulf and the breeding patterns of other gulf-breeding petrels—or they were breeding in late summer and autumn, much later than anyone had predicted.

A grant from the BirdLife International Community Conservation Fund enabled us to address the question of when the storm petrels were breeding.

White-faced storm petrels were used in a pilot study to test-drive telemetry equipment the team intended to use on their rarer cousins. It didn’t go well. In December 2011, Megan Young and Neil Fitzgerald attached 15 transmitters to white-faced petrels. While the automated receivers worked perfectly, the transmitters were a disaster. Antennas broke off, batteries corroded, and transmitters deteriorated until they failed. Only one performed as expected. We needed better transmitters if we were to track New Zealand storm petrels to their breeding sites.

While we wrestled with the transmitter issue, an intriguing observation was made in the field. Fitzgerald, who was photographing birds on a seabird trip I was leading, suddenly turned to me and, pointing to an image of a New Zealand storm petrel on the screen of his camera, said, “I think there’s a stick attached to this bird’s leg.” Sure enough, there was. But what kind of stick? With the help of botanists, we identified it as a slender petiole or leaf stalk from a Pseudopanax, a common local plant. No seabird biologist had seen anything like this. It was the first tangible proof that this bird had been on land, somewhere in northern New Zealand.

Soon after this came the breakthrough we were looking for. On February 2, 2012, the team caught a New Zealand storm petrel, and, lifting the bird’s belly feathers, discovered the skin to be completely bare in preparation for incubating an egg. From February through to May 2012, 20 birds were caught, and several had fully bare brood patches. Finally we had unequivocal proof that New Zealand storm petrels were breeding locally. As the captures were spread over several months, we could map out the birds’ likely breeding cycle in anticipation of mounting a major expedition to find out where they were breeding.

Late in February, just a few kilometres off Little Barrier, we tried something new: setting berley at night. Within a few minutes, a New Zealand storm petrel was seen amongst the birds attracted by the chum. Later, one landed on the boat, attracted by a spotlight, and we banded and measured it before releasing it. Seeing birds close to land at night reinforced Little Barrier as a likely breeding site, but we tempered that thought with the knowledge that the very first birds were seen in much the same location, and recent night-time sightings of two New Zealand storm petrels at the Hen and Chickens Islands, to the north-west, added to the uncertainty.

In September 2012, we received a set of Canadian transmitters that would meet our needs. The team trialled these units on winter-breeding diving petrels on Burgess Island in the Mokohinau group, and they worked perfectly. With funding from BirdLife International, the Mohammed bin Zayed Species Conservation Fund, the Little Barrier Island Supporters Trust and Forest & Bird, the 2013 programme was seen as our best—and perhaps only—chance of discovering the breeding site of the New Zealand storm petrel.

[Chapter break]

The expedition begins at sea on January 23, 2013, with the capture and radio-tagging of 24 storm petrels. Meanwhile, land-based teams deploy receivers on the Poor Knights and Burgess Island. They scan the airwaves at night for signals of birds fitted with transmitters making landfall.

Big seas delay the Little Barrier team, but finally, on Waitangi Day, Rayner and his party scramble ashore at Orau Cove on the north coast with plastic fish bins of equipment and supplies, fuel cans and a generator, dragging the lot inland and uphill through the bush towards the camp, a rough driftwood lean-to built by previous parties of DOC weed teams working in the area. Their enthusiasm for the site is moderated somewhat by the huge scars on the uphill side of each tree—damage caused by boulders that have come crashing down from clifftops 200 metres above.

On the same day, further along the coast, two of us make a very wet landing on a boulder beach to check one of the automated receivers that was set up on the island in January, and has been silently monitoring the radio spectrum for transmissions of tagged birds ever since. It sits neatly among stunted pohutukawa trees and kie kie, its green LED light blinking optimistically. At least it’s still running. I connect a laptop and download data. A quick scan through the numbers… three birds detected! After a brief celebration, and a few idiot yahoos, we descend to camp with the news. In the days that follow, we detect nine of the 24 birds that have been fitted with transmitters at this location before we move the receiver to another site on the island.

Over the next few weeks the boat crew has to contend with tsunami warnings and difficult trips in total darkness along the remote northern shore of Little Barrier to drop off spotting teams.

“The coast is so beautiful, but very exposed, and we had a one-metre swell rolling in the whole time,” says Matt Rayner. “Spotlights proved less than ideal for long-range vision, so we ended up driving the inflatable in the pitch dark using a night-vision scope. We shocked a couple of guys fishing late one night when our lightless inflatable appeared out of nowhere in a rolling sea and stiff westerly laden with three guys, one wearing a night scope on his head.”

On the boats, we’re surrounded by marine life. Flying fish career towards our spotlights like missiles. We see a lot of sharks—13 hammerheads in one group, and a bronze whaler breaching. Birds, too: Cook’s petrels, the occasional Buller’s shearwater, and, sure enough, New Zealand storm petrels.

Over five nights, the team get a clear impression that the birds are flying inland after dark, possibly up the gorges, certainly beyond the huge cliffs. From the boats off the coast we see a good number of New Zealand storm petrels close to the shore. Some fly over us with a fluttery moth-like flight, so different from their determined swallow-like flitting when we see them at sea during the day. A few birds have transmitters and we can follow their flight without seeing them. While all this is happening on the north coast, Richard Walle, one of the two DOC rangers on the island, with his wife Leigh Joyce and their two children spend a weekend walking across the island. They land at Pohutukawa Flat, on the east coast, and spend the night there before climbing to Orau Hut, high on the island. After years of telemetry work with kakapo and other birds, Walle and Joyce are experts at tracking. At both Pohutukawa Flat and Orau Hut they detect several tagged birds. One of them flies up from the eastern coast, over the ridge, then down into one of the deep ravines that lead out to the north of the island. At least four more birds are tracked over two nights from the rangers’ home base on the western side of the island. This time the storm petrels appear to be either flying inland or coming out of valleys on the west side.

Armed with this exciting news, we pull the camp from the north coast and shift attention inland. The prospect is daunting, given the size and extremely rugged nature of the island.

Little Barrier is an ancient, weathered volcano. Ridges and deep, sheer-sided gorges radiate from a central cluster of high peaks, the highest being Mt. Hauturu (772 metres). In some places the gorges are so narrow that the walls overhang to resemble caves. The coastline is mostly high cliffs. Ridges end in steep headlands, and between them are boulder beaches. Forest clings to the slopes, except on cliff faces or where landslides scar valley walls. Little Barrier’s only flat land is on the western side, where waves and tidal currents flowing around the island have created a triangular-shaped boulder bank. Te Hauturu-o-Toi is an astonishingly beautiful island, but travel is singularly challenging, especially away from the handful of well-used ridge tracks.

That night, February 12, one group head for the tops and detect a tagged bird flying right around them. Another group on the flats near the ranger station also pick up signals.

The next day, we set up one of the automated receivers at The Thumb, one of the island’s high peaks. We climb with our gear into the mist through a dripping cloud forest of kauri, hard beech and subtropical broadleaf trees. Once the receiver station is set up, bristling with antennas, the team settle in and wait for dark.

[sidebar-3]

Every now and then the mist clears, just enough to glimpse the other summits and dark valley heads with their near-vertical walls.

With dark, the Cook’s petrels arrive en masse. Our headlamps and spotlights attract birds, and so many land around us that we have to shut down our lights. The birds’ calling is an extraordinary cacophony, from an incessant kek-kek-kekkek to purrs, moans, even drawn-out duck-like sounds. Underlying everything is the murmur of tens of thousands of birds flying and landing on the island’s summits and ridges.

In the midst of this other-worldly experience, New Zealand storm petrel transmitters are detected. Down towards the coast or out to sea, it’s hard to say. One bird appears to fly up towards us.

Several hundred metres below us, Graeme Loh and Sue Maturin work their way up one of the ridgeline tracks, while Richard Walle and Steffi Ismar follow the euphemistically named ‘coastal highway’—a rollercoaster-like trail that weed teams use to access the cliffs of the western coast. They also detect birds, probably the same ones we’re picking up. With the automated receiver running OK, we head down.

We’re about two-thirds of the way down when Loh calls over the radio, “We have a stationary signal.”

We stop, but we are two ridges and two valleys away. Another pair of researchers try to get closer via another ridge track, but they can’t pick up any signal. Loh and Maturin stay with the signal, and ultimately their persistence pays off. Walle and Ismar join them, after bush-bashing up from the coast. Loh and Walle clamber down the steep drop to the stream bed at the bottom of the gorge, then climb 50 metres through the dark forest from there. By 2am, they are right on top of the bird—it can be detected using their hand-held receiver without an antenna attached. But the site is very difficult, with steep ground and loose rock, and any burrow or crevice in which the bird might have its nest is under a mass of kie kie and deep leaf litter. It’s too fragile to interfere with.

With GPS and flagging tape, the team mark a huge X on their ‘treasure map’. The jubilant pair re-join Ismar and Maturin, and head back to base.

Breakfast is a big celebration, and we devise a new plan. Rayner and I are due to leave the island the next day, but we can now see the project stretching another two or three months. We need some advice to better inform our next steps, and more funds.

While Rayner and the rest of the team head for what we believe is a nest site, I get on the phone and email. By the end of the day, a couple of promises of funds will see us into April at least. The team sets up one of our automated receivers near the nest site to monitor the birds’ movements, and to see if any other birds are in the valley. A lot of effort goes into ensuring the system will run 24/7. Loh uses his tree-climbing skills to get a solar panel rigged into the crown of a tall beech tree.

Back on the mainland, I arrange to do some aerial surveys, working on the theory that any signals from our transmitters detected during the day will be from birds on nests, in burrows or crevices. When three flights in a fixed-wing plane fail to turn up any signals, we turn to a helicopter and fly up and down many of the island’s valleys and gorges. It’s spectacular flying, in parts of the island where people have probably never set foot, and it serves to remind us how fortunate we are to have located a breeding site in this extraordinary place. Yet the only signal we detect is from the valley we are already monitoring.

On February 19, most of the team depart Little Barrier. There are paying jobs for all these volunteers to get back to. Fortunately, our overseas volunteers (Ismar, David Boyle and Martin Berg) can stay on for a few extra nights before other commitments take them away. The extra time pays dividends. During long nights spent in the vicinity of our solitary nest site, they detect eight more birds. They see storm petrels flying through the forest just above their heads. Then, very early on the morning of February 22, I receive a text which reads: “We have just banded a NZSP.” It is the first New Zealand storm petrel seen on land and in the hand.

Before leaving, the team spend a day setting up a second receiver, remote cameras and sound recorders in the valley.

[Chapter break]

On March 8, we return to the island to check automated gear, download data and continue daytime searches. A stray signal is detected from a ridge track to the north of our known site, but it is lost again before the team can locate it. The same day, Walle finds a new breeding site upstream from the first site, more fragile even than the original one—a crumbly rock cliff face, also deep within forest. We know where the bird is, but can’t get our burrow-scope in far enough to see it on its nest. More recording gear is deployed.

New teams continue with the day-and night-surveying. On March 17, another bird is captured in the vicinity of the original nest site.

As this magazine goes to press, work continues. For as long as the transmitters continued to run, the team followed the progress of birds in the valley with the automated receivers. Remote video cameras recorded parent birds entering and leaving burrows at night, a specialist petrel-sniffing dog is being used to find more burrows, and more monitoring gear is being installed.

Then, on April 17, Megan Young carefully extracted a chick from its burrow, the very first New Zealand storm petrel chick seen in a century, probably longer. It was an unexpected highlight of a decade-long search for the team, though many questions remain to be answered.

One of the mysteries is how these diminutive birds survived when other seabirds didn’t.

Common diving petrels, fluttering and little shearwaters, and the larger grey-faced petrel either never nested on Little Barrier or were reduced to such low numbers their presence wasn’t detected. Vulnerable terrestrial species such as the Little Barrier Island snipe failed to survive the wild cats that dominated the island for so long. Seabirds such as the black petrel and Cook’s petrel were severely impacted by predators.

One possible reason the storm petrels managed to hang on is that they nested in rock crevices and amongst vegetation on the sea cliffs, places that were out of reach of cats and rats. However, as seabird expert Paul Scofield commented while looking at the steep, forested valley, “When we thought about where the birds could be breeding, that place would be the last place we thought of.”

Did the storm petrels spread inland from the cliffs during the eight and half years since rats were eradicated, or is there some other answer? One suggestion is that these tiny birds are able to nest in trees, among the epiphytes that garland big kauri and rata trees on the island.

Ian Southey, who worked on Little Barrier in the 1970s and 80s, commented after his visit this year on “the increase in kokako numbers and the incredible abundance of saddlebacks. Think of the other creatures that are emerging from the woodwork—the extremely rare chevron skink for one.” And now the New Zealand storm petrel.

Researchers remain unclear on how typical the known breeding sites are, and whether there might be other breeding sites scattered across the island. We have good reason to believe there are more sites awaiting discovery, with birds seen flying inland from the northern and eastern coasts.

Are New Zealand storm petrels also breeding on other islands in the Hauraki Gulf and northern New Zealand? There is a strong possibility they are, with the birds having been seen at sea from the Mercury Islands in the eastern Bay of Plenty all the way to North Cape and the Three Kings Group. This is a key conservation question to resolve, as a second breeding site on a separate island is vitally important to secure the future of this species. While they have survived on Little Barrier until now, they may not survive an invasion from more lethal predators such as ship and Norway rats, or stoats. Ongoing biosecurity of such precious refuges as Little Barrier Island is paramount.

Determining the likely New Zealand storm petrel population is impossible with current information, but will be investigated in coming years. The record of sightings at sea suggests their number is increasing—and although we could just be getting better at locating them, we’d like to think that the increase reflects a growing population.

The discovery that the New Zealand storm petrel was breeding on Little Barrier was a great relief. This island is one of New Zealand conservation’s crown jewels, especially since cats were finally eradicated in 1980 and Pacific rats (kiore) in 2004. According to the department’s Draft Auckland Conservation Management Strategy, Little Barrier “remains a priority ecosystem site due to its unique assemblage of indigenous plants and animals”. We can now add the New Zealand storm petrel to the list of those species sheltering in the long shadow of Little Barrier’s volcanic parapets.

And yet the future of the species, and of others in the cast of New Zealand’s most vulnerable wildlife, is far from certain. The Hauturu Supporters Trust contributes about $40,000 annually to DOC for conservation work on the island—an approach clearly in line with the department’s new direction for greater community effort. But how much more can trusts contribute, and what of the many other places, both within the gulf and elsewhere in New Zealand, that will never receive this level of community support?

The New Zealand storm petrel has clung to existence by the very slimmest of margins. Yet these tiny birds spend most of their lives at sea, where they survive wild seas and storms, and wrest food from a seemingly featureless ocean. Like all seabirds, they are supremely adapted to survive the immense odds nature can throw at them. Sadly, human impacts are a threat they will never survive long enough to adapt to.

But for now, finding the breeding site of an ‘extinct’ species is a small triumph. That the site is a mere 50 kilometres from our largest city is evidence of the great wealth of natural life still awaiting discovery, even right on our doorstep.